Aleksei Gan

Gan at work on a magazine cover, 1924. Photographed by Alexander Rodchenko. | |

| Born |

1887 vicinity of Moscow, Russian Empire |

|---|---|

| Died | September 8, 1942 |

Aleksei Gan (Алексей Михайлович Ган (Имберх); 1887[1]-1942) was a Russian designer and art theorist.

Life and work

In 1918–20 he was head of the section of mass performances and spectacles of the theatrical department of Narkompros, and he made a radical proposal for the entire population of Moscow to enact the May Day spectacle The Communist City of the Future (1920). This 'mass action' activity presaged the anti-aesthetic stance that was to characterize Gan’s approach. Late 1920 expelled from the state cultural bureaucracy on account of the excessive radicalism.

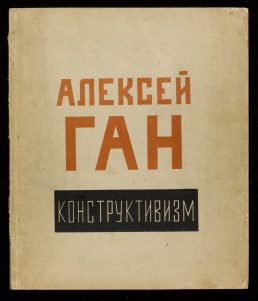

Through his co-founding with Stepanova and Rodchenko of the First Working Group of Constructivists (1921–4), and his publication of Constructivist principles in his book Konstruktivizm (1922), Gan played a leading role in the development of the Constructivist aesthetic. In his interpretation of Constructivism, which he saw as the creative counterpart to the socio-political tasks of the Revolution, Gan called for creative activity to be politicized to the maximum and for its artistic component to be minimized. His slogans included "we declare uncompromising war on art" and "death to art", which he attempted to encapsulate in his designs for portable book kiosks, folding street stalls, exhibition posters and clothing, where the objects were reduced to the most simple and functional forms.

It was this extreme approach that led to a split with fellow Constructivists Rodchenko and Stepanova in 1923 and his setting up of what he considered the true group of Constructivists, comprised of students at Vkhutemas. This group consisted of several production cells: the equipment for everyday life, children's books, specialized work clothes and typography, as well as cells concerned with material structures, mass action, and cinema and photography (Kino-Fot). The group exhibited their work at the First Discussional Exhibition of the Union of Active Revolutionary Art (Moscow, May 1924).

Gan also published and edited the journal Kino-Fot (1922–3), in which he advanced his idea of the replacement of painting by photography and promoted the cinema as a medium unconnected with tradition and capable of the objective recording of successful changes in Soviet life. He developed these theories in a book-long Constructivist film manifesto Da zdravstvuyet demonstratsiya byta! (Long Live the Demonstration of Daily Life!, Moscow, 1923) and in his articles for Sovremennaya arkhitektura (1926–30), the journal of OSA, for which he was artistic editor.

He was also a founding member of October (1928–32), a union of artists, designers and architects, which primarily advocated Constructivist ideals as the most suitable for the advancement of the material culture of Soviet society.

His first wife, Olga, died in 1920, and his only child, Katya, was raised from infancy by Olga's relatives in Ukraine. His partner during the twenties and early thirties was the filmmaker Esfir Shub.[2]

In November 1927, Gan entered the Donskaia Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital in an effort to recover from a combination of nervous exhaustion and alcoholism, remaining under the care of Donskaia's doctors off and on until 1930.[3]

Gan was arrested in October 1941 for participating in counterrevolutionary propaganda and agitation, tried and found guilty in August 1942, and executed 8 September 1942. He was rehabilitated in 1989.[4]

Film

- The Island of the Young Pioneers, 1924. Documentary.

Publications

- "Борьба за «Массовое Действо»", in O teatre [О театре], Tver: Tverskoe izdatelstvo, 1922, pp 49-80. (Russian)

- Konstruktivizm [Конструктивизм], Tver: Tverskoe izdatelstvo, Oct-Dec 1922, [2]+70 pp (23,5х19,9 cm — edition of 2000). [1] (Russian)

- "Constructivism" [Extracts], trans. John Bowlt, in The Tradition of Constructivism, ed. Stephen Bann, New York: Viking Press, 1974, pp 32-42; repr. in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902-1934, ed. & trans. John E. Bowlt, New York: Viking Press, 1976, pp 214-225; repr. in Art in Theory, 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Blackwell, 1992, pp 318-320. (English)

- "Der Konstruktivismus", trans. Annelore Nitschke, in Am Nullpunkt. Positionen der russischen Avantgarde, eds. B. Groys and A. Hansen-Löve, Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 2005, pp 277-365. (German)

- Constructivism, trans. & intro. Christina Lodder, Barcelona: Tenov Books, 2014, xciii+77 pp. [2] Reviews: Rees (RAC 2014), Taplin (RBTH 2014), Hatherley (RP 2015), Rosenfeld (SEER 2015). (English)

Correspondence

- "'...Болезнь моя иного порядка'. Письма Алексея Гана Эсфири Шуб" ['...My ilness is of another mode'. Letters from Alexei Gan to Esfir Shub], Kinovedcheskie zapiski 49 [Киноведческие записки] (2000), Moscow, pp 222-228. Gan’s letter to Esfir Shub, disclosing their differences concerning development of domestic cinema of the 1920s and presenting hard attempts at self identification of one of the founders of Constuctivism under post-revolutionary regime. [3](Russian)

- "Письмо Эсфири Шуб Алексею Гану" [A letter from Esfir Shub to Alexei Gan], Kinovedcheskie zapiski 49 [Киноведческие записки] (2000), Moscow, pp 229-230. The last letter from Esfir Shub to Alexei Gan. [4] (Russian)

Literature

- Books and theses

- A.N. Lavrentiev (А. Н. Лаврентьев), Aleksei Gan [Алексей Ган], S.E. Gordeev, 2010, 192 pp. [5] (Russian)

- Kristin Romberg, Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917-1928, New York: Columbia University, 2010, 576 pp. Ph.D. Dissertation. (English)

- Articles

- Vitalii Zhemchuzhnyi, "Aleksei Gan: Konstruktivizm", Zrelishcha 9 (Oct 1922) p 8. (Russian)

- Alexander Lavrentiev, "Zagadki Alekseia Gana", Da 2-3 (1995), p 3. (Russian)

- Catherine Cooke, "Sources of a Radical Mission in the Early Soviet Profession: Aleksei Gan and the Moscow Anarchists", in Architecture and Revolution: Contemporary Perspectives on Central and Eastern Europe, ed. Neil Leach, London and New York: Routledge, 1999, pp 13-37. (English)

- A.Konopleva-Shub (А.Б.Коноплева), "Aleksei Mikhailovich Gan" [Алексей Михайлович Ган], Kinovedcheskie zapiski [Киноведческие записки] 49 (2000), Moscow, pp 212-221. Memoirs of Esfir Shub's daughter about her step-father. (Russian)

- Kristin Romberg, "Aleksei Gan's Constructivism", Center 29, Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2009, pp 120-123. (English)

- Kristin Romberg, "Labor Demonstrations: Aleksei Gan's Island of the Young Pioneers, Dziga Vertov's Kino-Eye, and the Rationalization of Artistic Labor", October 145 (Summer 2013), pp 38-66. (English)