Central and Eastern Europe

Contents

- 1 Light-music synthesis

- 2 Constructivists, Futurists

- 3 Literature, literary theory, aesthetics

- 4 Photography

- 5 Light art

- 6 Experimental film

- 7 Geometric abstraction, Neo-constructivism, Op art, Kinetic art

- 8 Audiovisual compositions

- 9 Cybernetics

- 10 Electroacoustic music

- 11 Multimedia environments

- 12 Computer art, Dynamic objects, Cybernetic sculpture

- 13 Video

- 14 New media art, Media culture

- 15 Media theory

- 16 Art theory, history, and criticism

- 17 Local histories

- 18 See also

- 19 Support

Light-music synthesis

People

- 1900s-20s: Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (Warsaw/Vilnius), A.N.Scriabin, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, Mikhail Matyushin (St. Petersburg), Alexander László, Arnošt Hošek, Zdeněk Pešánek (Prague), Miroslav Ponc (Prague)

Networks

- Prometei, Kazan, 1960s-2000s

Colour organs

- There will be a day when a composer will compose music with a notation that will be conceived in terms of music and light… and that day, the artistic unity we were talking about will probably be closer to perfection.., Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, 1925.

- (Colour) pianos (or organs) were constructed by the likes of Alexander Scriabin (with Preston Millar), Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, Alexander László, and Zdeněk Pešánek (with Erwin Schulhoff) in an attempt to navigate between musical and visual realms.

- Scriabin composed a color-music piece Prometheus: The Poem of Fire (1911) and contracted Preston Millar to build an instrument to produce colors along to the music, named Chromola (Clavier à lumières; tastiéra per luce; keyboard with lights).

- Futurist painter Baranoff-Rossiné's instrument introduced patterns and shapes into a color organ, built upon a modern piano, thus called the Optophonic Piano (Piano optophonique). The piano projected light through painted and rotating glass plates, whose colors, shapes and rhythms closely complemented the music (1916, developed since 1912); it was presented in the Theatre of Vsevolod Meyerhold, at his exhibition in Kristiana in Oslo (1916), and in the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow (1924). Baranoff-Rossiné performed until the late 1920s, but his work was displayed in several museums in Europe and the US from 1966 to 1975.

- Alexander László, a Hungarian raised in Germany, a pianist and orchestra conductor, composed and performed music for various silent films in 1900s-10s. Arguing for a relation between the film and the music, he wrote a theoretical text on color-light-music, "Farblichtmusik" (1925). The theories were brought into practice in a series of performances across Europe. His device, Sonchromatoscope, consisted of a few switches above his piano, controlling a few projection lights and a slide projector lightning the stage above the piano. When the first reviews arrived, the main remark was that the projections were too simple. It was in a completely different league than the Chopin-like complexity of the piano music. In those days Oskar Fischinger was experimenting with abstract films. László contacted him to help improve his performance. Multiple extra slide projectors and overlapping projection lights were added to increase the complexity and the number of possible colors. This resulted in a a visual spectacle which completely turned the reviews over. Both László and Fischinger have toured with the show. [1]

- With their Spectrophon-Piano (1928), Pešánek and Schulhoff attempted to create an audio-visual sculpture. The piano enabled the dynamic synthesis of music and coloured light in performances in big concert halls.

Events

- See This Sound exhibition, Linz, 2009. [2]

Literature

- Alexander László, Die Farblichtmusik, Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1925, xii+71 pp.

- Hans Scheugl, Ernst Schmidt, "Lichtkunst", in Eine Subgeschichte des Films: Lexikon d. Avantgarde-, Experimental- u. Undergroundfilms, 2, Frankfurt am Main, 1974. (German)

- Teun Lucassen, "Color Organs", n.d.

- Cornelia Lund, Holger Lund (eds.), Audio.Visual - On Visual Music and Related Media, 2009, 320 pp. Book with DVD. [3] (English)/(German)

- See This Sound: Versprechungen von Bild und Ton / Promises in Sound and Vision, eds. Cosima Rainer, Stella Rollig, Dieter Daniels and Manuela Ammer, Cologne: Walther König, 2010, 320 pp. (German)/(English)

- Jörg Jewanski, "Color Organs", See This Sound Compendium, c2010.

- Jan Schneider, Lenka Krausová (eds.), Intermedialita: Slovo-Obraz-Zvuk: Sborník příspěvku ze sympozia, Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2008, 336 pp. (Czech)

- Manifesty pohyblivého obrazu: barevná hudba, eds. Martin Bernátek, Kateřina Krejčová, Martin Mazanec, and Matěj Strnad, Olomouc: Pastiche Filmz/PAF, 2010, 106 pp. Reader. [4] (Czech)

- Kateřina Drajsajtlová, Světelný klavír v uměleckém díle Alexandera Nikolajeviče Skrjabina a Zdeňka Pešánka, Brno: Masaryk University, 2012. Bc thesis. [5] (Czech)

- Bibliography

- "Bibliography: Synesthesia in Art and Science", comp. Crétien van Campen (editor), Greta Berman, Anton V. Sidoroff-Dorso and Bulat Galeyev, Leonardo, 2012.

See also

Further bibliography.

Constructivists, Futurists

Terms

formism (1910s, Chwistek, Czyżewski), Pure Form (1920s, Witkiewicz), strefism (1920s, Chwistek), mechano-faktura (1920s, Berlewi), unism (1920s, Strzemiński), photogenism (1920s, Funke), robot (1920s, Čapek)

People

- 1910s-20s: Wassily Kandinsky (Moscow/Weimar), Kazimir Malevich (Moscow/St. Petersburg), Naum Gabo (Moscow/Berlin), Vladimir Tatlin (Moscow), El Lissitzky (Moscow/St. Petersburg/Vitebsk), Alexander Rodchenko (Moscow), Lajos Kassák (Budapest), László Moholy-Nagy (Berlin/London), Leon Chwistek (Krakow/Lwow), Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Warsaw), Anatol Stern (Warsaw), Karel Teige (Prague), Josef Vydra (Bratislava), Jaromír Funke (Prague/Bratislava), Henryk Berlewi (Warsaw/Berlin/Paris), Ljubomir Micić (Zagreb/Belgrade), Josip Seissel (Jo Klek; Zagreb), Ion Vinea (Bucharest), Marcel Janco (Bucharest), Victor Brauner (Bucharest/Paris), Władysław Strzemiński (Warsaw/Lodz), Katarzyna Kobro (Warsaw/Lodz), Mieczyslaw Szczuka (Warsaw), Avgust Černigoj (Trieste/Ljubljana), Ferdo Delak (Ljubljana), Vytautas Kairiūkštis (Vilnius), Jaan Vahtra (Tartu)

Networks, Journals

- MA, Budapest/Vienna, mid 1910s-mid 1920s

- Bauhaus, Weimar/Dessau/Berlin, 1920s-mid 1930s

- Productivist Group and VkHUTEMAS, Moscow, 1920s

- Devětsil, Prague, 1920s

- Zwrotnica, Krakow, 1920s

- Blok, Warsaw, 1920s; Praesens, Warsaw, late 1920s; a.r., Lodz, 1930s

- Zenit, Zagreb and Belgrade, 1920s

- Travelers, Zagreb, 1920s

- Group of Estonian Artists, Tartu and Tallinn, 1920s

- Contimporanul, Bucharest, 1920s

- 75HP and Punct, Bucharest, mid-1920s

- Tank, Ljubljana, late 1920s

- School of Arts and Crafts, Bratislava, 1930s

Events

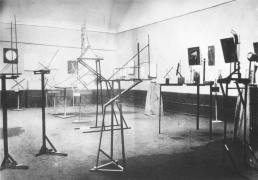

- OBMOKhU exhibitions in Moscow in May 1920 and May-June 1921. Some OBMOKhU members became part of the First Working Group of Constructivists, formed in the spring of 1921 at the Moscow Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK).

- Constructivists [Конструктивисты] exhibition in Moscow, January 1922. Georgii Stenberg, Vladimir Stenberg and Konstantin Medunetsky show 61 constructivist works and publish a catalogue with manifesto. [6]

- The Congress of International Progressive Artists [Kongress der Union Internationaler Fortschrittlicher Künstler] in Düsseldorf on 29-31 May 1922. Formation of the International Faction of Constructivists was organised by Theo Van Doesburg (representing the journal De Stijl), Hans Richter (representing 'the Constructivist groups of Romania, Switzerland, Scandinavia and Germany') and El Lissitzky (representing the editorial board of Veshch'-Gegenstand-Objet). The faction's declaration was later published in De Stijl (no. 4, 1922).

- Congress of the Constructivists and Dadaists, Weimar, 25-26 Sep 1922.

- The First Russian Art Exhibition [Erste russische Kunstausstellung] opened at Galerie van Diemen in Berlin on 15 October 1922, with over 1,000 objects by c180 artists: 237 paintings, more than 500 graphic works, sculptures, as well as designs for theater, architectural models, and porcelain. The exhibition's official host was the Russian Ministry for Information, and it was put together by the artists Naum Gabo, David Sterenberg, and Nathan Altman. Version of the exhibition later travelled to Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, in April-May 1923.

- New Art Exhibition [Wystawa Nowej Sztuki], organised by Władysław Strzemiński and Vytautas Kairiūkštis in Vilnius in May-June 1923. A meeting ground for the Eastern and Western European avant-garde movements.

- The Block of Cubists, Constructivists and Supermatists [Blok Kubistów, Suprematystów i Konstruktywistów], an exhibition of the Blok collective at the Laurin & Clement car dealer's shop in Warsaw, March 1924. Works by 9 artists.

- First Zenit International Exhibition of New Art [Прва Зенитова међународна изложба нове уметности], organised by Ljubomir Micić in April 1924 in Belgrade. Featured one hundred works advertised as "futurism, cubism, expressionism, ornamental cubism, suprematism, constructivism, neoclassicism and the like".

- The First Contimporanul International Exhibition organised by Contimporanul magazine in November 1924 in Bucharest brought together almost the entire Romanian avant-garde along with international artists.

- The a.r. International Collection of Modern Art, donated by a.r. group to the Municipal Museum of History and Art (now Museum of Art; Museum Sztuki) in Lodz, opened to the public in February 1931. It included 111 works and represented - as no other contemporary European collection had done - the main movements of avant-garde art, from Cubism, Futurism and Constructivism, through Purism and Surrealism, to Neo-Plasticism, Unism and Formism.

- Retrospective exhibitions

- Europa, Europa. Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und Osteuropa, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, 27 May - 16 October 1994.

- Central European Avant-Gardes, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2002, curated by Timothy O. Benson, included c300 artworks.

Literature

- Catalogues

- Europa, Europa. Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und Osteuropa, eds. Ryszard Stanislawski and Christoph Brockhaus, Bonn, 1994. Contributions from c150 authors. Four volumes: Vol I (five introductory essays followed by 73 short texts on the work of specific artists) 479 pp. incl. 247 col. pls. and 116 b&w ills.; Vol II (36 essays on aspects of architecture, literature, theatre, film and music) 239 pp. incl. 251 b&w ills.; Vol III, compiled by Hubertus Gassner (354 short texts of the period 1894-1994 by artists, critics etc., in German translation), 367 pp.; Vol IV (biographies; selected bibliography; list of exhibited works; index) 99 pp. [7] [8] (German)

- Central European Avant-Gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910-1930, ed. Timothy O. Benson, forew. Péter Nádas, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002, 447 pp. Publisher. Review: Zusi (SEEJ). (English)

- Von Kandinsky bis Tatlin: Konstruktivismus in Europa/From Kandinsky to Tatlin: Constructivism in Europe, Schwerin: Staatliches Museum; and Bonn: Kunstmuseum, 2006. (German)/(English)

- Vzplanutí. Expresionistické tendence ve Střední Evropě 1903-1936, ed. Ladislav Daněk, Olomouc: Muzeum umění Olomouc, 2008, 200 pp. [9] (Czech)

- Anthologies

- The Tradition of Constructivism, ed. & intro. Stephen Bann, New York: Viking Press, 1974, xlix+334 pp, PDF. Fifty-one texts from 1920-65 in 7 sections. Review: Compton (SR 1975). (English)

- Between Worlds: A Sourcebook of Central European Avant-Gardes, 1910-1930, eds. Timothy O. Benson and Éva Forgács, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002, 736 pp. Review: Zusi (SEEJ), Glanc (ArtMargins). (English)

- Books

- George Rickey, Constructivism: Origins and Evolution, New York: G. Braziller, 1967, xi+306 pp, OL; rev.ed., 1995, xi+306 pp. (English)

- Willy Rotzler, Konstruktive Konzepte: eine Geschichte der konstruktiven Kunst vom Kubismus bis heute, Zurich: ABC, 1977, 299 pp; new ed., 1988, 332 pp; 3rd ed., 1995, 332 pp. (German)

- Krisztina Passuth, Les avant-gardes de l'Europe Centrale, 1907-1927, Paris: Flammarion, 1988, 327 pp. (French)

- Avantgarde kapcsolatok Prágától Bukarestig 1907-1930, Budapest: Balassi, 1998, 381 pp. (Hungarian)

- Treffpunkte der Avantgarden: Ostmitteleuropa 1907–1930, trans. Aniko Harmath, Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 2003, 337 pp. Review: Dmitrieva-Einhorn (H-Soz-Kult 2006). (German)

- Lothar Lang, Konstruktivismus und Buchkunst, Leipzig: Edition Leipzig, 1990, 208 pp. TOC. (German)

- S.A. Mansbach, Modern Art in Eastern Europe: From the Baltic to the Balkans, ca. 1890-1939, Cambridge University Press, 1999, 384 pp, IA. (English)

- Dubravka Djurić, Miško Šuvaković (eds.), Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918-1991, MIT Press, 2003, xviii+605 pp. (English)

- Vojtěch Lahoda (ed.), Local Strategies, International Ambitions: Modern Art and Central Europe 1918-1968, Prague: Artefactum, 2006, 243 pp. Papers from the international conference, Prague, 11-14 Jun 2003. TOC. Papers: Anna Brzynski, Maria Elena Versari. [10] [11]

- Elizabeth Clegg, Art, Design, and Architecture in Central Europe 1890-1920, Yale University Press, 2006, 356 pp. [12] (English)

- Sascha Bru, et al. (eds.), Europa! Europa? The Avant-Garde, Modernism and the Fate of a Continent, 1, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2009. (English)

- Günter Berghaus (ed.), Futurism in Eastern and Central Europe, De Gruyter (International Yearbook of Futurism Studies 1), 2011. (English)

- Sarah Posman, Anne Reverseau, David Ayers, Sascha Bru, Benedikt Hjartarson (eds.), The Aesthetics of Matter: Modernism, the Avant-Garde and Material Exchange, De Gruyter, 2013. (English)

- Beata Hock, Klara Kemp-Welch, Jonathan Owen (eds.), A Reader in East-Central European Modernism, 1918-1956, London: Courtauld Books Online, 2019, 432 pp, PDFs, HTML. Review: Drobe (Craace). (English)

- Beate Störtkuhl, Rafał Makała (eds.), Nicht nur Bauhaus – Netzwerke der Moderne in Mitteleuropa / Not Just Bauhaus – Networks of Modernity in Central Europe, Oldenbourg: De Gruyter, 2020, 400 pp. Publisher. Review: Secklehner (Art East Central). (German),(English)

- Journal issues

- Art Journal 49(1): "From Leningrad to Ljubljana: The Suppressed Avant-Gardes of East-Central and Eastern Europe during the Early Twentieth Century" (Spring 1990). [13] (English)

- Centropa 3(1): "Central European Architectural Students at the Bauhaus", New York: Centropa, Jan 2003. [14] (English)

- Centropa 6(2): "Central European Artists and Paris: 1920s-1930s", ed. Irena Kossowska, New York: Centropa, May 2006. [15] (English)

- Centropa 11(1): "Central European Art Groups, 1880-1914", ed. Anna Brzyski, New York: Centropa, Jan 2011. [16] (English)

- Articles, talks

- Folke Dietzsch, "Zu einigen Aspekten der Internationalität des Bauhauses und seiner Studentenschaft", Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift / A // Hochschule für Architektur und Bauwesen 33:4/6 (1987). (German)

- Esther Levinger, "The Second Narrative, Constructivism in East-Central Europe", Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass, 2002. Colloquium talk. (English)

See also

Avant-garde in Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Romania, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania. Further bibliography.

Literature, literary theory, aesthetics

Terms

structuralism (1920s, Prague Linguistic Circle), linguistic functionalism (1920s, Prague Linguistic Circle), proletkult (1920s, international), Poetism (1920s, Teige and Nezval), factography (1920s, LEF), aesthetic object (1930s, Ingarden), phoneme (Jakobson), morphophonology (Trubetzkoy), genetic structuralism (1960s, Goldmann), communicative functions (1960s, Jakobson)

People

- 1910s-30s: Vladimir Mayakovsky (Moscow), Josip Brik (St. Petersburg/Moscow), Nikolai Trubetzkoy (Moscow/Vienna), Viktor Shklovsky (St. Petersburg/Berlin), Petr Bogatyrev (Moscow/Prague), Roman Jakobson (Moscow/Prague), Jan Mukařovský (Prague), Karel Teige (Prague), Vítězslav Nezval (Prague), Jaroslav Seifert (Prague), Bedřich Václavek (Prague), Roman Ingarden (Lwow), György Lukács (Berlin/Moscow/Budapest)

- 1960s: Lucien Goldmann (Bucharest/Paris), Felix Vodička (Prague)

Networks

- Russian Formalists, Moscow Linguistic Circle and OPOYEZ in St. Petersburg, 1910s-20s

- Prague Linguistic Circle, 1920s-30s

- Devětsil, Prague, 1920s

- LEF, Moscow, 1920s

Photography

Terms

photogram, photo-eye, photomontage, photogenism (1922, Funke), heliography (1928, Hiller)

People

- 1920s: László Moholy-Nagy (photograms, Berlin/London), Alexander Rodchenko (Moscow), Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina (photomontages, Riga/Moscow), Franciszka and Stefan Themerson (Warsaw), Mieczysław Szczuka (photomontage, Warsaw), Vane Bor (surrealist, Belgrade/Paris), Jaromír Funke (Prague/Bratislava), Karel Teige (theory, Prague), Jindřich Štyrský (surrealist, Prague), Jaroslav Rössler (Prague/Paris), Karol Hiller (heliography, Łódź)

- 1930s: Eugen Wiškovský (Prague), Irena Blühová (social photography, Bratislava), Lubomír Linhart (theory, Prague)

See also

Photography in Czech Republic, Slovakia.

Light art

People

- 1920s-30s: Naum Gabo (Moscow/Berlin), László Moholy-Nagy (Hungary/Berlin/London), István Sebök (Budapest/Vienna/Dessau), El Lissitzky (Moscow/St. Petersburg/Vitebsk), Nikolas Braun (Berlin), Zdeněk Pešánek (Prague)

- 1970s: Antoni Mikołajczyk (Łódź), Stanislav Zippe (Prague)

Experimental film

Terms

montage (1920s, Eisenstein), Kino-Pravda (1922, Vertov), Cine-Eye (1920s, Vertov), cinema club, Open Form (1950s-60s, Hansen), antifilm (1962, Pansini)

People

- 1920s-40s: Sergei Eisenstein (Moscow), Dziga Vertov (Moscow), Alexander Hammid (Prague), Otakar Vávra (Prague), Franciszka and Stefan Themerson (Warsaw)

- 1960s: Radúz Činčera (Prague), Vladimir Petek (Zagreb), Mihovil Pansini (Zagreb), Tomislav Gotovac (Zagreb), Ivan Martinac (Split), Živojin Pavlović (Belgrade), Karpo Godina (Ljubljana), Ivica Matić (Sarajevo)

- 1970s-80s: Gábor Bódy (Budapest/Berlin), Jozef Robakowski (Lodz), Zbigniew Rybczynski (Lodz), Miklós Erdély (Budapest), Wojciech Bruszewski (Lodz), Vladimír Havrilla (Bratislava), Petr Skala (Prague)

- 1990s-2000s: Lukasz Ronduda (theorist, Warsaw)

Events

GEFF festival (Zagreb, 1963-70), MAFAF festival (Pula, 1965-90), 8 mm (Novi Sad), Alternative Film Festival (Split), April Meetings festival (Belgrade, 1972-77), Alternative Film & Video Festival (Belgrade, *1982), xfilm festival and series of lectures / screenings (Sofia, since 2005), This Is All Film! Experimental Film in Yugoslavia 1951-1991 exhibition (Ljubljana, 2010)

Networks

- Zagreb Cinema Club, Zagreb, 1930s and 1950s-60s

- Start film club and SAF film co-operative, Warsaw, 1930s

- Split Cinema Club, Split, 1950s-60s and 1980s

- Balázs Béla Studio, Budapest, 1960s-1980s

- Open Form, Lodz and Warsaw, 1960s-70s

- Sarajevo Cinema Club, Sarajevo, 1960s

- Workshop of Film Form, Lodz, 1970s

- Belgrade Cinema Club and Academic Film Center Belgrade, Belgrade, 1960s-70s; Black Wave, Belgrade, 1970s

- Kinema Ikon, Arad, 1975-1990

- Sigma group, Timisoara, 1970s

- Parallel Cinema (necrorealist movement), St. Petersburg and Moscow, mid 1980s

Literature

- Lukasz Ronduda, Florian Zeyfang (eds.), 1,2,3 -- avant-gardes : film, art between experiment and archive, Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw ; Berlin ; New York : Sternberg, 2007.

- Ana Janevski (ed.): As Soon as I Open My Eyes I See a Film. Experiment in the Art of Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1970s, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, 2010. With essays by Ana Janevski (on experimental art and film in Yugoslavia), Stevan Vuković (on political upheaval in 1968 in Belgrade), and Łukasz Ronduda (on contacts between Yugoslav and Polish artists in the 1970s). [17] Interview with Ana Janevski, June 2011

- Bojana Piškur et al (eds.), This Is All Film: Experimental Film in Yugoslavia 1951-1991 [Vse to je film: Eksperimentalni film v Jugoslaviji 1951-1991], catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, 2010. 154 pages. ISBN: 9789612060909

See also

Experimental film in Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania, Estonia, Lithuania. Further bibliography.

Geometric abstraction, Neo-constructivism, Op art, Kinetic art

Terms

visual kinetics (plastique cinétique, 1950s, Vasarely)

People

- late 1940s-60s: Victor Vasarely (Budapest/Paris), Nicolas Schöffer (Hungary/Paris), Zdeněk Sýkora (Prague), Exat 51 group (Zagreb), Gyula Kosice (Košice/Buenos Aires)

- 1960s-70s: Milan Dobeš (Bratislava), Dvizheniye group (Moscow, incl. Lev Nusberg and Francisco Infante), 111 group (Timisoara), Piotr Kowalski (Lwow/Paris), Bulat Galeev (Kazan), Gyula Pauer (Budapest), Zbigniew Gostomski (Warsaw), Ryszard Winiarski (Warsaw), Diet Sayler (Romania/Germany), Juraj Dobrović (Zagreb), Sigma group (Timisoara)

See also

Slovakia, Hungary, Romania. Further bibliography.

Audiovisual compositions

People

- 1960s-70s: Alois Piňos (Prague), Petr Kotík (Prague), Milan Grygar (Prague), Bulat Galeyev (Kazan)

See also

Audiovisual compositions in Czech Republic, Slovakia. Further bibliography.

Cybernetics

See Computing and cybernetics in CEE.

Electroacoustic music

Trivia

- Lev Termen, the patriarch of musical electronics, a talented physicist, created Aetherophone (later called the Theremin or Thereminovox) in 1920 - unsurpassed till now in the family of performing electronic instruments (owing to its keen sound control options).

- Other early instruments include Sonchromatoskop by Sándor László (1920), Sonar by N.Anan'yev (c1930), Ekvodin by V.A.Gurov (1931), Emiriton by A.Ivanov and A.Rimsky-Korsakov (1932). While in the United States, Termen also created Theremin Cello (electric Cello with no strings and no bow, using a plastic fingerboard, a handle for volume and two knobs for sound shaping, c1930), Theremin keyboard (a piano-like device, c1930), Rhythmicon (world's first drum machine, 1931), and Terpsitone (platform that converts dance movements into tones, 1932). In the 1930s, professor E.A.Sholpo established a laboratory for sound synthesis where he developed his Variophone (1932), a precursor of the synthesizers. A.A.Volodin, a scientist in the field of electronic sound synthesis, designed a whole series of new instruments.

- In Moscow, Eugene Murzin constructed one of the world's first synthesizers in 1955. He named his invention, ANS synthesizer, in honor of Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin, as the ANS worked on the principle of the transformation of light waves into electronic soundings. The compositions created on the ANS in the Moscow Studio of Electronic Music since 1958 played the major role in the development of electronic music in USSR. In the 1960s, the ANS was the only synthesizer in the Union, and became the training ground of a great number of young composers, including one of the most dedicated experimenters in the field of electronic music, Edward Artemyev. Artemyev's compositions are characterized by a constant search for new sounds and by a desire to obtain maximum timbre modification from minimal sound material. In the music for A. Tarkovsky's film Solaris (1972), Artemyev discovered an entire realm of unusual (for that time) sound effects; he founded a new trend in electronic music that musicologists have named 'space music'. (In 1972 the studio acquired the module synthesizer "SYNTHI-100" of English company "Taylor".)

- Warsaw Autumn Festival initiated by Baird and Serocki presented since 1956 works by Berg, Schönberg, or Bartók; Stockhausen or Schaeffer visited. Polish Radio Experimental studio was founded by Patkowski in 1957.

- In Czechoslovakia, the first representative Seminar on Electronic Music, organized on the initiative of several Czech and Slovak composers, musicologists and sound technicians, was held at the Research Institute of Radio and Television in Pilsen in 1964. It appeared a miracle to many people interested in this kind of musical creativity. The seminar dealt seriously and manifestly with questions of electronic music, for the first time in Czechoslovak cultural context. The representative survey on electronic music written by Czech musicologist Vladimir Lebl and published in 1966 was the fundamental theoretical work, followed by his translation of the book "La Musique concrete" by Pierre Schaeffer. Several compositions by the classicists of concrete, tape and electronic music appeared in radio broadcasts in 1965 and the first LP with electronic music pieces by both inland and foreign composers was published as soon as in 1966. Followed by foundation of experimental music studios in Bratislava (1965) and Pilsen (1967).

- During 1950s-70s the number of composers visited New Music courses in Darmstadt (Kotonski, Piňos, Jeney, Sáry), studied and worked with studios WDR Cologne (Kotonski, Eötvös, Dubrovay), GRM Paris (Kotonski, Kabeláč, Piňos, Vidovszky), Munich (Piňos), STEM Utrecht (Kabeláč), or IRCAM Paris (Eötvös).

- Gorizont became known as some sort of Russian version of Kraftwerk, releasing an LP by the "Soviet State" record label Melodia.

Terms

musique concréte (1949, Schaeffer, Paris), elektronische Musik (1950, Eimert and Meyer-Eppler, Cologne), New Music, synthesizer (ANS synthesizer, 1955, Moscow; RCA Music synthesizer, 1955), white noise, vocoder, atonal music, serialism

Studios

Polish Radio Experimental Studio Warsaw (1957, Patkowski), Experimental studio of electronic music Moscow (1958, Murzin), Experimentalstudio für künstliche Klang- und Geräuscherzeugung East Berlin (1953 or 1962?), Experimental Studio of Slovak Radio Bratislava (1965, Kolman), Experimental Studio of Czech Radio Pilsen (1967-94), New Music Studio Budapest (1970), Electronic Studio of Radio Belgrade (1972, Radovanović), Electro-acoustic Music Studio at Academy of Music Krakow (1973, Patkowski), Electronic music studio Sofia (1974), Electroacoustic Music Studio of the Hungarian Radio Budapest (1975, Decsényi), Studio for Electronic Music Dresden (1984, Wissmann), Audiostudio of Czechoslovak Radio Prague (1990-94), Theremin Center Moscow (1992, Smirnov), Electronic Music Studio at the Estonian Academy of Music Tallinn (1995, Sumera) more

People

- mid-1950s-60s: Jozef Patkowski (Warsaw), Wlodzimierz Kotonski (Warsaw), Evgeny Murzin (engineer, Moscow), Edward Artemiev (Moscow), Peter Kolman (Bratislava), Miloslav Kabeláč (Pilsen), Vladimír Lébl (musicologist, Prague), Antonín Sychra (musicologist, Prague), Milan Knížák (Prague)

- 1970s: Vladan Radovanović (Belgrade), Péter Eötvös (Budapest), Zoltán Jeney (Budapest), László Vidovszky (Budapest), László Sáry (Budapest)

- 1980s: Mindaugas Urbaitis (Kaunas)

- 1990s: Andrey Smirnov (Moscow), Lepo Sumera (Tallinn)

Events

- 1950s-60s: Warsaw Autumn Festival (Warsaw, *1956), International Seminars on New Music (Smolenice, 1968-70), Exposition of Experimental Music (Brno, 1969-70).

- 1990s: Evenings of New Music (Bratislava, *1990), IFEM and FEM festival (Bratislava, 1992-96), Exposition of New Music (Brno, *1993).

- 2000s: Next festival (Bratislava, *1999), X-Peripheria festival (Budapest, *2000)

Literature

- Lejaren A Hiller, Report on Contemporary Music, 1961 (Technical Report no. 4), Urbana, Il.: Experimental Music Studio, University of Illinois, 1962.

- Golo Föllmer, Markus Steffens, Melanie Uerlings (eds.), Sound Exchange. Anthology of Experimental Music Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe 1950-2010, Saarbrücken: PFAU, 2012, 400 pp, HTML. (English),(multiple languages)

- David Crowley, Daniel Muzyczuk, Sounding the Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957-1984 / Dźwięki elektrycznego ciała: Eksperymenty w sztuce i muzyce w Europie Wschodniej 1957–1984, Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2012, 222 pp. (English)/(Polish)

- Daniel Muzyczuk, David Crowley, Michał Libera, "Sounding the Body Electric: A Conversation", ArtMargins, 8 October 2012.

- UMCSEET. Unearthing The Music: Creative Sound And Experimentation under European Totalitarianism 1957-1989, OUT.RA, 2018, 75 pp. Wiki database. Project website. (English)

- Jorge Munnshe, "Electronic Music in Eastern Europe", pt 1: USSR, pt 2: Russia, pt 3: Kazakhstan, Ukraine, pt 4: Hungary, pt 5: Czechoslovakia, pt 6: Poland, East Germany, pt 7, Amazing Sounds, n.d.

See also

Electroacoustic music in East Germany, Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Serbia, Croatia, Romania, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia. Further bibliography. See also Audiovisual tools and instruments, Electronic art music, The International Documentation of Electroacoustic Music and [18].

Multimedia environments

People and works

- 1950s-60s: Josef Svoboda's Laterna Magika, Diacran, Polyecran, and Diapolyecran (Prague), Jaroslav Frič's Polyvision and Vertical Cinemascope (Prague), Dvizheniye group's Cybertheatre (Moscow, incl. Lev Nusberg and Francisco Infante), Stano Filko's Cathedral of Humanism (Bratislava), Jerzy Rosołowicz's Neutrdrom (Wroclaw), VAL group's Heliopolis (Bratislava)

- 1970s: Attila Kováts (Cologne/Budapest)

- 1980s: András Mengyán (Budapest)

Literature

See also

Multimedia environments in Czech Republic, Hungary. Further bibliography.

Computer art, Dynamic objects, Cybernetic sculpture

Terms

new materials, information aesthetics (1960s, Bense and Moles)

People

- 1950s: Nicolas Schöffer (cybernetic sculpture, Hungary/Paris)

- 1960s: Vladimir Bonačić (dynamic objects, Zagreb), Petar Milojević (Belgrade/Toronto)

- 1970s: Edward Ihnatowicz (cybernetic sculpture, Poland/London), Stanisław Dróżdż (concrete poetry, Poland), Zdeněk Sýkora (computer-aided painting, Prague), Jozef Jankovič (computer prints, Bratislava), Juraj Bartusz (computer-aided sculpture, Bratislava), Ryszard Winiarski (paintings and objects, Warsaw), Mihai Jalobeanu (computer graphics, Cluj), Sherban Epuré (Romania/New York City), Zoran Radović (Belgrade/Berlin), Sergej Pavlin (Ljubljana)

- 1980s: Tamás Waliczky (Budapest), Vladan Radovanović (Belgrade)

- 1990s: Zoltán Szegedy-Maszák (Budapest), Jan Pamula (Krakow), Alexandru Patatics (Timisoara)

Events, Networks

- New Tendencies, Zagreb, 1960s-mid 70s

Works

Literature

- Dušan Barok, "Looking to the Future: Science, Technology, and Utopia", in Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s, ed. Pavel S. Pyś, Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 2023, pp 445-460. Exhibition. (English)

See also

Computer art in Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria. Further bibliography.

Video

Terms

new art practices (1970s)

People

- 1970s: Woody Vasulka (Prague/New York City), Jozef Robakowski (Lodz), Wojciech Bruszewski (Lodz), Antoni Mikołajczyk (Lodz), Ryszard Waśko (Lodz), Nuša and Srečo Dragan (Ljubljana), Miha Vipotnik (Ljubljana), Sanja Iveković (Zagreb), Dalibor Martinis (Zagreb), Goran Trbuljak (Zagreb), Ivan Faktor (Osijek)

- 1980s: Pawel Kwiek (Warsaw), Petr Skala (Prague), Team T group, Izabella Gustowska (Poznań), Yach-Film group, Marina Abramović (Novi Sad/Belgrade/Amsterdam), Raša Todosijević (Belgrade), Krzysztof Wodiczko (Warsaw/New York City/Boston)

- 1990s: Peter Rónai (Bratislava), Cãlin Dan (Bucharest/Amsterdam), Apsolutno group (Novi Sad), Ando Keskküla (Tallinn), Jaan Toomik (Tallinn), Deimantas Narkevicius (Vilnius), Ryszard Kluszczynski (theorist, Lodz/Poznan)

Events

April Meetings festival (Belgrade, 1972-77), Video CD biennial (Ljubljana, 1983-89), WRO Biennale (Wroclaw, since 1989), Sub Voce exhibition (Budapest, 1991), French-Baltic-Nordic Video and New Media Festival (Riga/Vilnius/Tallinn, *1992), Ex Oriente Lux exhibition (Bucharest, 1993), Videomedeja festival (Novi Sad, *1996), New Video, New Europe exhibition (Chicago, 2004), E.U. Positive exhibition (Berlin, 2004), Instant Europe (Udine, 2005)

Networks

- FAVIT, Ljubljana, 1970s

- Student Cultural Center, Belgrade, since 1970s

- Infermental, Berlin and international, 1980s

- ŠKUC, Ljubljana, 1980s

- Video Salon, Prague, late 1980s

- WRO, Wroclaw, 1990s-2000s

Archives

- Transitland archive, 1990s-2000s

See also

Video in Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia (2), Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Romania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania. Further bibliography.

New media art, Media culture

Terms

mailing list, discussion forum, media lab (1990s-2000s), net art (1990s), streaming, tactical media, hacker culture, audiovisual performance, digital signal processing (DSP), Pure Data, Max/MSP, vvvvv, SuperCollider, online social network

People

- 1990s-2000s: János Sugár (Budapest), Miloš Vojtěchovský (Prague), Keiko Sei (Prague/Brno), Nina Czegledy (Budapest/Toronto), Stephen Kovats (Dessau), Silver (Prague), Alexei Shulgin (Moscow/London), Olia Lialina (Moscow), Inke Arns (Berlin), Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits (Riga), Luchezar Boyadjiev (Sofia), Cãlin Dan (Bucharest), Vuk Ćosić (Ljubljana), Marko Peljhan (Ljubljana), Igor Štromajer (Ljubljana), John Grzinich (Mooste), Ákos Maróy (Budapest/New York City), Petko Dourmana (Sofia), Ivor Diosi (Bratislava/Prague), Guy van Belle (Brussels/Bratislava), Jakub Nepraš (Prague), Rene Beekman (Amsterdam/Sofia), Krassimir Terziev (Sofia)

Events

The Media Are With Us conference (Budapest, 1990), Ostranenie (Dessau, 1993/95/97/99), Orbis Fictus exhibition (Prague, 1994), Hi-tech/Art exhibition and symposium series (Brno, 1994-97), MetaForum conferences (Budapest, 1994-96), Butterfly Effect (Budapest, 1996), Dawn of the Magicians? (Prague, 1996-97), LEAF conference (Liverpool, 1997), Beauty and the East Nettime conference (Ljubljana, 1997), Communication Front (Plovdiv, 1999-2001), Media Forum (Moscow, *2000), Enter Multimediale festival (Prague, 2000/05/07/09), Multiplace festival (Bratislava/Prague/Brno/international, *2002), FM@dia (Prague, 2004), Trans european Picnic (Novi Sad, 2004), Remake exhibition (Brno/Bratislava/Cluj, 2012).

Networks

- Soros Center of Contemporary Arts (loose) network: C3 (Budapest), Ljudmila (Ljubljana), Radio Jeleni (Prague), MediaArtLab (Moscow), mid 1990s-early 2000s

- V2_East / Syndicate, international, mid 1990s-2000

- Nettime, international, mid 1990s-2000s

- Media Research Foundation and C3, Budapest, 1990s

- Arkzin, Zagreb, 1990s

- Terminal Bar and NoD Media Lab, Prague, mid 1990s-early 2000s

- E-lab and RIXC, Riga, mid 1990s-2000s

- Kuda.org, Novi Sad, mid 1990s-2000s

Literature

- Ostranenie catalogues

- Ostranenie: 1. Internationales Videofestival am Bauhaus Dessau, 4.-7.11.1993: erschütterte Mythe, neue Realitäten: Osteuropa im Focus der Videokamera / 1. Meždunarodnyj videofestival v Bauchaus Dessau: poshatnuvshiesya myfy, novaya deystvitelnost: vostochnaya Evropa v fokuse videokamery / 1. International Video Festival at the Bauhaus Dessau: Shattered Myths, New Realities: Video Focus on Eastern Europe, eds. Inke Arns and Elisabeth Tharandt, Dessau: Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, 1993, 499 pp. Selected texts: Erjavec, Arns, Sei, Kovats, Kuhn, Milev, Sobetzko, Czegledy, Performances, more. [19] [20] (German),(Russian),(English)

- OSTranenie '95: das internationale Video-Forum an der Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau / The International Video Forum at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation: Video, Installation, Performance, Workshop: 8.-12. November, eds. Mirja Rosenau, Stephen Kovats, Thomas Munz, and Tina Rehn, Dessau: Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, 1995, 403+14 pp. [21] [22] (German)/(English)

- Ostranenie '97: Dessau 5.-9. Dezember 1997: das internationale Forum elektronischer Medien / the International Electronic Media Forum, eds. Mirja Rosenau and Stephen Kovats, Dessau: Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, 1997, 553 pp. [23] [24] (German)/(English)

- Ost-West Internet: elektronische Medien im Transformationsprozess Ost- und Mitteleuropas / Media Revolution: Electronic Media in the Transformation Process of Eastern and Central Europe, ed. Stephen Kovats, Frankfurt am Main/New York: Campus (Edition Bauhaus 6), 1999, 381 pp. ISBN 9783593363653. TOC, TOC. Review: Broeckmann (Leonardo). [25] [26] [27] (German)/(English)

- Ostranenie 93 95 97, ed. Stephen Kovats, Dessau: Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, 1999. CD-ROM, Mac & PC. ISBN 3910022308. Documents the works and impressions of over 400 artists, critics, academics and journalists from 32 countries who participated in the Ostranenie events from 1993 to 1997. Produced by the Studio Electronic Media Interpretation of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation in cooperation with C3 - Soros Foundation Budapest. [28] [29]

- ZK Proceedings 95: Net Criticism, eds. Geert Lovink and Pit Schultz, Amsterdam, Jan 1996. Published on the occasion of Next 5 Minutes 2. [31] [32] [33] (English)

- ZKP2: A Portable Net Critique, eds. Diana Mc Carty, Pit Schultz, and Geert Lovink, Madrid, Jun 1996. Published on the occasion of 5Cyberconf. [34] [35] [36] [37] (English)

- ZKP3: The Metaforum III Historical Files, eds. Thomas Bass, Geert Lovink, Diana McCarty, and Pit Schulz, Budapest, Oct 1996. Published on the occasion of MetaForum 3. [38] [39] (English)

- (ZKP4) The Beauty and the East. Filtered by Nettime, eds. Pit Schultz, Diana McCarty, Geert Lovink, and Vuk Cosic, Ljubljana, May 1997. Published on the occasion of Beauty and the East. See also "The Piran Nettime Manifesto", [41]. (English)

- Netzkritik. Materialien zur Internet-Debatte, eds. Pit Schultz and Geert Lovink, trans. Bettina Seifried, Florian Rötzer and Thomas Atzert, Berlin: ID-Verlag, 1997, 220 pp. [42] (German)

- (ZKP5) ReadMe! ASCII Culture & The Revenge of Knowledge. Filtered by Nettime, eds. Josephine Bosma, Pauline van Mourik Broekman, Ted Byfield, Matthew Fuller, Geert Lovink, Diana McCarty, Pit Schultz, Felix Stalder, McKenzie Wark, and Faith Wilding, New York: Autonomedia, Feb 1999, 556 pp. [43] (English)

- (NKP6) Net.art Per Me. Catalogue of the Slovenian Pavillion, Venice: Venice Biennale, 2001. [44] (English)

- V2_East Reader: Syndicate Meeting on Documentation and Archives of Media Art in Eastern, Central and South-Eastern Europe, eds. Inke Arns and Andreas Broeckmann, Rotterdam: V2_Organisatie (Syndicate Publication Series 000), Sep 1996. (or see the web documentation on archive.org) (English)

- Deep Europe: The 1996-97 Edition. Selected Texts from the V2_East/Syndicate Mailing List, eds. Inke Arns and Andreas Broeckmann, Berlin: V2 Organisation (Syndicate Publication Series 001), Oct 1997, 143 pp. Published on the occasion of the Ostranenie '97 festival at the Bauhaus Dessau. [45] (English)

- Junction Skopje: The 1997-1998 Edition. Selected Texts from the V2_East/Syndicate Mailing List, ed. Inke Arns, Skopje: Soros Center for Contemporary Arts Skopje (Syndicate Publication Series 002), Oct 1998, 197 pp. Published on the occasion of the Junction/Syndicate Meeting, Skopje (2-4 Oct 1998) held during the Skopje Electronic Arts Fair '98: Communing. Announcement. (English)

- Deep_Europe newsletter archive, Hybrid Workspace, Kassel, 1997.

- other

- Inke Arns, Andreas Broeckmann, "Small Media Normality for the East", Rewired, Jun 1997, PDF. (English)

- "Kleine östliche Mediennormalität", diss.sense, Konstanz: University of Konstanz, May 1998. (German)

- Convergence 4(2): "New Media Cultures in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe", ed. Inke Arns, University of Luton Press, Summer 1998. (English)

- Rossitza Daskalova, "The Ground for Net.art in the Former Eastern Block (Central and Eastern Europe)", CIAC's Electronic Magazine 12, Montreal: CIAC, Jan 2001. (English)

- Rossitza Daskalova, "Web Projects", CIAC's Electronic Magazine 12, Montreal: CIAC, Jan 2001. (English)

- Slavomír Krekovič, "New Media Culture. Internet as a Tool of Cultural Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe", in Crossing Boundaries: From Syria to Slovakia, eds. S. Jakelic and J. Varsoke, Vienna: IWM Junior Visiting Fellows' Conferences, 2003. (English)

- Dušan Barok, Magdaléna Kobzová (eds.), Save Before It's Gone, Brussels, 2006. Includes interviews with Dirk Paesmans, Maja Kuzmanovic, Darko Fritz, and Andrei Smirnov. (English)

- Miklós Peternák, "The Illusion of the Initiative: An Overview of the Past Twenty Years of Media Art in Central Europe" / Die Illusion der Initiative. Über die Medienkunst der letzten zwanzig Jahre in Ost- und Mitteleuropa", in Gateways: Art and Networked Culture, eds. Sabine Himmelsbach, KUMU Art Museum Tallinn, Goethe Institut Estland and Ralf Eppeneder, Hatje Cantz, 2011. [46] [47] (English)/(German)

- 3/4 27-28: "Remake", ed. Barbora Šedivá, Bratislava: Atrakt Art, 2012. [48] (English)/(Slovak)

- Bogumiła Suwara, Mariusz Pisarski (eds.), Remediation: Crossing Discursive Boundaries: Central European Perspective, Berlin: Peter Lang, and Bratislava: Veda, 2019, 368 pp. (English)

See also

Media labs, Media art festivals, Media art conferences

Media theory

People

Vilém Flusser (Prague/Germany/Brazil)

Events

The Media Are With Us (Budapest, 1990), Prague Media Symposium (Prague, 1991-98), MetaForum (Budapest, 1994-96), Mutamorphosis (Prague, 2007)

Art theory, history, and criticism

People

Jindřich Chalupecký (Prague), Tomáš Štrauss (Bratislava/Germany), Ješa Denegri (Belgrade), Bojana Pejić (Belgrade/Berlin), Jiří Valoch (Prague), Boris Groys (Moscow/Berlin), Igor Zabel (Ljubljana), Miško Šuvaković (Belgrade), Marina Gržinić (Ljubljana), Miklós Peternák (Budapest), Piotr Piotrowski (Poznan/Warsaw), Viktor Misiano (Moscow), Éva Forgács (Budapest/Pasadena), Keiko Sei (Brno/Karlsruhe/Thailand), Tomáš Pospiszyl (Prague), IRWIN (Ljubljana), Boris Buden (Zagreb), Georg Schöllhammer (Vienna), Reuben Fowkes (Budapest), Gerald Raunig (Vienna), Dejan Sretenović (Belgrade), Dmitry Vilensky (St. Petersburg), David Crowley.

Networks

Third Text, Springerin magazine (Vienna), Tranzit (Vienna), EIPCP (and Transversal journal, Vienna), Chto delat (St. Petersburg), SocialEast, Prelom magazine (Belgrade), IDEA Arts+Society magazine (Cluj), ARTMargins (int), Artyčok (Prague)

Local histories

| Countries avant-garde, modernism, experimental art, media culture, social practice |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Albania, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Central and Eastern Europe, Chile, China, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kosova, Latvia, Lebanon, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Morocco, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Norway, Pakistan, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Slovenia, Slovakia, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States | ||

See also

Support

The research was supported by cOL-mE, International Visegrad Fund, and ERSTE Foundation.

Contributors include Dušan Barok, Guy van Belle, Nina Czegledy, Lenka Dolanová, Eva Krátká, Magdaléna Kobzová, Barbora Šedivá, Joanna Walewska, Darko Fritz, Miro A. Cimerman, Matko Meštrović, Paul Stubbs, Rarita Szakats, Călin Man, Raluca Velisar, Miklós Peternák, János Sugár, Pit Schultz, Diana McCarty, Barbara Huber, Maxigas, Miloš Vojtěchovský, Grzegorz Klaman, František Zachoval, Sølve N.T. Lauvås, and many others.