Ideographies of Knowledge/Introduction

Introductory talk to the symposium Ideographies of Knowledge, 3 October 2015.

"Once one read, today one refers to, checks through, skims." Ever since I've read that sentence some months ago it has stucked in my mind. It's its catchy rhythm that made me memorise it immediately. Itself it is a quote from a tome bringing Otlet's writings to the Anglophone audience, translated by his biographer W. Boyd Rayward. Look how deep it is "buried" inside. [PIC] Can you see it?

Regardless, here we have a phrase that is set to have a life on its own, to be transmitted aurally and orally, without necessary reference to a text.

In its rhythmical singularity it is also a lament. It is a lament about information overload from more than one century ago. Shelves and tabletops continued to be buried under assorted newspapers and magazines, libraries had to throw out ever more books to make space for new ones. Most people did not mind. But Otlet did.

He has set out to make it easier for everyone to find.. anything.. that has been written down. From compiling a bibliography of writings on law in Belgium, he moved on to do so with sociology across borders and languages, to end up attempting to list everything ever published. To structure that enterprise, the then existing classification systems turned out insufficient. His Universal Decimal Classification system was made more "modular" -- branches and subbranches of knowledge were assigned numbers and could be combined according to a set of rules. So when a researcher in Germany sent a written request for a list of publications on travels between Germany and Italy, staff at the International Institute of Bibliography (IBB) in Brussels looked inside drawers relevant for 910.4(430:450) and copied bibliographic records from index cards onto a sheet of paper and sent it back.

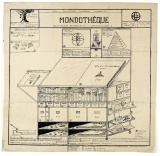

The bibliographic institute was just a beginning of Otlet's lifelong journey [PIC] to organise the world's records. His attention would soon turn to microfilm, telephone and other new media of the time, as well as to ideas about networked institutions on the one hand and personal "knowledge machines" on the other [PIC] (of which Mondotheque was an early beta).

Classification had been his main guiding principle. A guiding structuring principle that would not stop on the surface of the document, on the surface of the book, but would be used to translate it into classes from within. [PIC] Fragments of knowledge were meant to be mined, recombined and carried around to serve the humankind and bring about peace.

So Otlet had worked on ways of providing the search of world's records through classes, beyond manually compiled indexes printed inside books. But while those could not stand up to the task, today's search engines operate under the imperative of the total index. Books are being digitised and all words they contain indexed, to make findable any sequence of text, image or sound across vast collections. The more the better. Big data, or just any data is treated like goods for the good, the better. http://aaaaarg.fail/research?query=once+one+read+today+one+refers+to

However, classification practices are as common today as ever before -- whether in taxonomies, metadata and tagging, or in reference models and ontologies of concepts, those ever-changing standards used to make data compatible within and across databases.

..

This event is set to explore the legacy of Paul Otlet's work and the practises of documentation, classification, indexing and data visualisation, especially how they affect the ways we read and write today.

We have invited ten digital librarians, media theorists, designers, researchers and artists from various places. Each was asked to submit three "artifacts" related to the theme. The 30 so collected things take various forms, including concepts, stories, software prototypes, texts, videos, websites, tangible objects, own work. These were in turn grouped into six thematic sessions which will structure the debate. Each session is given 45 minutes and includes short presentations of the artifacts by their selectors (5 minutes each), the remaining time is reserved for discussion.