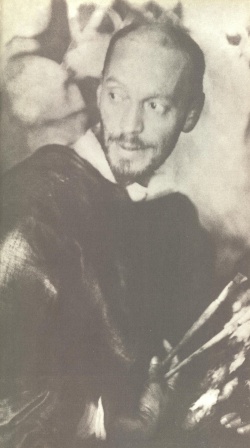

Nikolai Kulbin

| |

| Born |

May 2, 1868 St. Petersburg (or Helsinki) |

|---|---|

| Died |

March 6, 1917 (aged 48) Petrograd (today St. Petersburg), Russia |

Nikolai Ivanovich Kulbin (Николай Иванович Кульбин) was a Russian military doctor, painter, graphic artist, theatrical designer, art theorist, music theorist and patron of Russian Futurism.

Practise as a physician

Kulbin graduated as a physician from the Military Academy of Medicine in St. Petersburg (1887-1892), and was awarded degree of Doctor of Medicine from the Clinic of Professor F.I. Pasternatsky for dissertation on alcoholism in 1895. From 1893 he was a member of the Society for the Protection of Peoples' Health and teacher at the St. Petersburg Military-Medical Attendants' School, publishing several scientific articles between 1896-1907. He worked as a surgeon at the Russian Army Headquarters between 1903 and 1917[1], and made a General and Full State Councillor, 1907. Kulbin began to study microscopic drawing in 1888 and micro-photography in 1894.[2]

St. Petersburg's avant-garde years (1908-17)

Between 1908 and 1910, Kulbin was in the centre of the avant-garde scene in St. Petersburg, maintaining that all objects in the world were alive and that life itself was based on the universal principles of harmony and dissonance. He took up art in 1908 at the age of forty, founding the Triangle: The Art and Psychology Group (of fourteen painters and a sculptor) and organised the Exhibition of Modern Trends in Art, which was the first ever show of avant-garde art in St. Petersburg. Subsequently he organised and participated in many avant-garde exhibitions in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Vilnius, Baku, Ekaterinodar, and had solo exhibitions in October 1912 and June 1918.[3][4][5]

He was a founding member and decorator of Stray Dog cabaret cellar, founder of the Ars society (1911) and the Spectator society (1912-13) and shortly worked as main decorator at the Terioki Theatre (summer 1912) and the Queen of Spades Theatre (December 1913-January 1914).[6]

Kulbin was running a salon, a kind of informal association (in Russia this kind of establishment was called kruzhok, which was a very popular form of informal association, most typical for artists, poets and musicians all around the country) that included most Russian avant-garde artists, composers, poets, scholars and so forth, which permitted him to spread his ideas among the artistic community. It was Kulbin who arranged Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's visit to Russia in 1914.[7]

While Wassily Kandinsky was living abroad, he relied on friends back home to keep him apprised of cultural developments in Russia. When Arnold Schoenberg set off for St. Petersburg in 1912, Kandinsky arranged for his friend, Kulbin to meet him at the train station. “Kulbin knows everything, that is, he knows all the artists of importance,” Kandinsky wrote in a letter to Schoenberg. [1]

Free music: microtonality

During this time Kulbin declared the liberation of sound from its captivity by tradition. His theoretical treatise Free music. Musical applications of the new theory of artistic creativity was based on his lectures conducted in 1908 and was printed in St. Petersburg in 1909. In 1912 it was published in Munich in the collection Der Blaue Reiter Almanac edited by Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky. Its significance for Russia was comparable with that of the Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music published by Ferruccio Busoni in Europe in 1907.[8] He asserted:

"New possibilities are hidden in the sources of art itself, in nature. We are small organs of the living Earth, the cells of its body. Let’s listen to its symphonies, which make up part of the common concert of the Universe. It is a music of nature, natural Free music... Everybody knows that the sounds of the sea and wind are musical, that thunder develops a wonderful symphony, and of the music of birds."[9]

Anticipating the upcoming musical trends he advocated, amazingly for the time, quarter and eighth-tone music:

"The music of nature is free in its choice of notes — light, thunder, the whistling of wind, the rippling of water, the singing of birds. The nightingale sings not only the notes of contemporary music, but the notes of all the music it likes. Free music follows the same laws of nature as does music and the whole art of nature. Like the nightingale, the artist of free music is not restricted by tones and halftones. He also uses quarter tones and eighth tones and music with a free choice of tones."[10]

Art theory

Kulbin developed his art theory on the basis of his physiological and neurological studies. For him, the physical action of the universal movement of colour or sound served as outer stimuli that caused psychical effects in the spectator’s brain. Kulbin declared harmony and dissonance to be basic principles of art.[11]

"A series of still unknown phenomena is revealed:

The close connection of tones and the processes of close connection.

These connections of adjunct tones of a scale, of quarter tones or even lesser intervals, may still be called close dissonances, but they possess special characteristics that customary dissonances do not.

These close connections of tones evoke unusual sensations in man.

The vibration of closely connected tones is extremely exciting.

In such processes the irregular beat and the interference of tones (which is similar to that of light) are of great significance.

The vibration of close connections, their unfolding, their manifold play, make the representation of light, colours, and everything living much more effective than customary music does."[12]

Legacy

Although he died on 6 March 1917 just after the February revolution, his influence on the young generation of revolutionary artists and scholars was significant. Among his direct or indirect followers were Arseny Avraamov (expanding on microtonal music in his articles in 1914-16), Leonid Sabaneev, Arthur Lourié and many others.[13]

Literature

- By Kulbin

- Svobodnaya muzyka. Primeneniye novoy teorii khudozhestvennogo tvorchestva k muzyke [Свободная музыка. Применение новой теории художественного творчества к музыке], St. Petersburg, 1909, 7 pp. (in Russian) [2]

- "Slobodnaya muzika. Rezultaty primeneniya teorii khudozhestvennogo tvorchestva k muzyke" [Свободная музыка. Результаты применения теории художественного творчества к музыке], in Studiia impressionistov, ed. Nikolai Kulbin, St. Petersburg: Butovskoi, 1910, pp 15-26. (in Russian) [3]

- "Die Freie Musik", in Der Blaue Reiter, eds. Kandinsky and Franz Marc, 1912; 2nd. Ed., 1914, pp 69-73. (in German)

- "Chto est' slovo", in Gramoty i deklaratsii russkikh futuristov, St. Petersburg, 1914. (in Russian)

- "Chto takoe kubizm'", in Strelets, Petrograd, 1915, pp 197-216. (in Russian)

- On Kulbin

- Kulbin [Кульбин], St. Petersburg: Изд. Общества Интимного театра, 1912. (in Russian). Kulbin's biography, list of works, reproductions of selected works and articles by Sergei Sudeikin, Nikolai Evreinov and Sergei Gorodetsky. [4] [5] [6]

- Evgeny F. Kovtun, Russkaya futuristicheskaya kniga [Русская футуристическая книга], Moscow: Kniga, 1989, 248 pp. (in Russian) [7] [8]

- Evgeny F. Kovtun, Sangesi: die russische Avantgarde. Chlebnikow und seine Maler, Kilchberg/Zürich: Ed. Stemmle, 1993. (in German)

- Jeremy Howard, Nikolai Kul'bin and the Union of Youth, 1908-1914, University of St Andrews, 1991, 576 pp.

- Howard, Jeremy (1992). The Union of Youth: An Artists’ Society of the Russian Avant-Garde. Manchester University Press ND. [9]

- Smirnov, Andrey (2013). Sound in Z: Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Early 20th-century Russia. London: Koenig Books & Sound and Music.

Notes

- ↑ Smirnov 2013, p. 23

- ↑ Howard 1992, p. 226

- ↑ Howard 1992, pp. 13-16

- ↑ Howard 1992, p. 226

- ↑ Smirnov 2013, pp. 22-24

- ↑ Howard 1992, p. 226

- ↑ Smirnov 2013, pp. 22-24

- ↑ Smirnov 2013, p. 23

- ↑ Trans. Andrey Smirnov.

- ↑ See three versions of "Free Music" in the bibliography section.

- ↑ Smirnov 2013, p. 24

- ↑ See three versions of "Free Music" in the bibliography section.

- ↑ Smirnov 2013, p. 24