Difference between revisions of "Plato/Republic/Jowett"

(Created page with "{{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection=top}} ==Passages== {{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection=341}} <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection|341}}}|341| ====Jowett==== Now, I s...") |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Passages== | ==Passages== | ||

| − | {{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection= | + | {{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection=1.341d-342e}} |

| − | <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection| | + | <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection|1.341d-342e}}}|1.341d-342e| |

====Jowett==== | ====Jowett==== | ||

Now, I said, every art [''τέχνη''] has an interest [''συμφέρω''] ? <br> | Now, I said, every art [''τέχνη''] has an interest [''συμφέρω''] ? <br> | ||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

}}</onlyinclude> | }}</onlyinclude> | ||

| − | {{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection= | + | {{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection=1.345e-347a}} |

| − | <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection| | + | <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection|1.345e-347a}}}|1.345e-347a| |

====Jowett==== | ====Jowett==== | ||

[...] Then why in the case of lesser offices do men never take | [...] Then why in the case of lesser offices do men never take | ||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

}}</onlyinclude> | }}</onlyinclude> | ||

| − | {{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection= | + | {{:Plato/Republic|transcludesection=7.533a-c}} |

| − | <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection| | + | <onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection|7.533a-c}}}|7.533a-c| |

====Jowett==== | ====Jowett==== | ||

And assuredly no one will argue [533b] that there is any other | And assuredly no one will argue [533b] that there is any other | ||

Revision as of 12:56, 26 September 2014

The Republic (Περὶ πολιτείας; Peri politeias) is Plato (Πλάτων)'s best-known work and has proven to be one of the most intellectually and historically influential works of philosophy and political theory. In it, Socrates along with various Athenians and foreigners discuss the meaning of justice (δικαιοσύνη) and examine whether or not the just man is happier than the unjust man by considering a series of different cities coming into existence "in speech", culminating in a city (Kallipolis) ruled by philosopher-kings; and by examining the nature of existing regimes. The participants also discuss the theory of forms, the immortality of the soul, and the roles of the philosopher and of poetics in society. It was written sometime between 380 and 360 BCE.

The division of the Republic into ten books is due not to Plato but to his early editors and probably to the length of the papyrus rolls ("books") on which the dialogues were written. (Larson 1979:xx)

G.J. Boter in his book on the transmission history of the text (1989) recognizes its three primary witnesses: Parisinus gr. 1807 (A), Venetus Marcianus gr. 185 (coll. 576) (D) and Vindobonensis suppl. gr. 39 (F). Besides them, there are eleven papyri containing fragments of the Republic, all dating from the second and third century CE.

Passages

| The following three passages contain only a small fragment of the Republic and are selected to illustrate various uses of the notion of technê in Plato. For full translations, consult the bibliography below. |

Passages

1.341d-342e

The interest of technê is in its subject rather than in itself; as can be shown by the example of medicine.

| Edition: Adam 1903. Translations: Jowett 1871/88 EN, Grube/Reeve 1974/97 EN, Badiou/Spitzer 2013 EN. |

Jowett

Now, I said, every art [τέχνη] has an interest [συμφέρω] ?

Certainly.

For which the art has to consider [φύω] and provide [ἐκπορίζω] ?

Yes, that is the aim of art.

And the interest of any art is the perfection [μάλιστα τελέαν] of it this and

nothing else? [341e]

What do you mean ?

I mean what I may illustrate negatively by the example of

the body. Suppose you were to ask me whether the body is

self-sufficing or has wants, I should reply: Certainly the body

has wants; for the body may be ill and require to be cured,

and has therefore interests to which the art of medicine

ministers; and this is the origin [παρασκευάζω] and intention of medicine,

as you will acknowledge. Am I not right ? [342a]

Quite right, he replied.

But is the art of medicine or any other art faulty or

deficient in any quality in the same way that the eye may be

deficient in sight or the ear fail of hearing, and therefore

requires another art to provide for the interests of seeing

and hearing--has art in itself, I say, any similar liability to

fault or defect, and does every art require another

supplementary art to provide for its interests, and that another and

another without end ? [342b] Or have the arts to look only after

their own interests ? Or have they no need either of

themselves or of another ?--having no faults or defects, they have

no need to correct them, either by the exercise of their own

art or of any other; they have only to consider the interest

of their subject-matter. For every art remains pure and

faultless while remaining true--that is to say, while perfect

and unimpaired. Take the words in your precise sense, and

tell me whether I am not right.

Yes, clearly.

Then medicine [342c] does not consider the interest of medicine,

but the interest of the body ?

True, he said.

Nor does the art of horsemanship consider the interests of

the art of horsemanship, but the interests of the horse;

neither do any other arts care for themselves, for they have

no needs; they care only for that which is the subject of

their art ?

True, he said.

But surely, Thrasymachus, the arts are the superiors and

rulers of their own subjects?

To this he assented with a good deal of reluctance.

Then, I said, no science or art considers or enjoins the

interest of the stronger or superior, but only the interest

of the subject and weaker ? [342d]

He made an attempt to contest this proposition also, but

finally acquiesced.

Then, I continued, no physician, in so far as he is a

physician, considers his own good in what he prescribes, but

the good of his patient; for the true physician is also a ruler

having the human body as a subject, and is not a mere

money-maker; that has been admitted ?

Yes.

And the pilot likewise, in the strict sense of the term, is a

ruler of sailors [342e] and not a mere sailor ?

That has been admitted.

And such a pilot and ruler will provide and prescribe for

the interest of the sailor who is under him, and not for

his own or the ruler's interest ?

He gave a reluctant 'Yes.'

Then, I said, Thrasymachus, there is no one in any rule

who, in so far as he is a ruler, considers or enjoins what is

for his own interest, but always what is for the interest of his

subject or suitable to his art; to that he looks, and that alone

he considers in everything which he says and does. (1888:19-20)

1.345e-347a

Technai are also differentiated according to their dunamis. The true ruler and artist seek not their own advantage, but the perfection of their technai.

| Edition: Adam 1903. Translations: Jowett 1871/88 EN, Grube/Reeve 1974/97 EN, Badiou/Spitzer 2013 EN. |

Jowett

[...] Then why in the case of lesser offices do men never take

them willingly without payment, unless under the idea that

they govern for the advantage not of themselves but of

others ? [346a] Let me ask you a question: Are not the several

arts different, by reason of their each having a separate

function ? And, my dear illustrious friend, do say what you

think, that we may make a little progress.

Yes, that is the difference, he replied.

And each art gives us a particular good and not merely a

general one--medicine, for example, gives us health;

navigation, safety at sea, and so on ?

Yes, he said.

And the art of payment has the special function of giving

pay : but we do not confuse this with other arts, any more

than the art of the pilot is to be confused with the art of

medicine, because the health of the pilot may be improved by

a sea voyage. You would not be inclined to say, would you,

that navigation is the art of medicine, at least if we are to

adopt your exact use of language ?

Certainly not.

Or because a man is in good health when he receives pay

you would not say that the art of payment is medicine ?

I should not.

Nor would you say that medicine is the art of receiving

pay because a man takes fees when he is engaged in healing ?

Certainly not.

And we have admitted, I said, that the good of each art is

specially confined to the art ?

Yes.

Then, if there be any good which all artists have in

common, that is to be attributed to something of which they all

have the common use ?

True, he replied.

And when the artist is benefited by receiving pay the

advantage is gained by an additional use of the art of pay,

which is not the art professed by him ?

He gave a reluctant assent to this.

Then the pay is not derived by the several artists from

their respective arts. But the truth is, that while the art of

medicine gives health, and the art of the builder builds a

house, another art attends them which is the art of pay.

The various arts may be doing their own business and

benefiting that over which they preside, but would the artist

receive any benefit from his art unless he were paid as well ?

I suppose not.

But does he therefore confer no benefit when he works for

nothing ?

Certainly, he confers a benefit.

Then now, Thrasymachus, there is no longer any doubt

that neither arts nor governments provide for their own

interests; but, as we were before saying, they rule and

provide for the interests of their subjects who are the weaker

and not the stronger--to their good they attend and not to

the good of the superior. And this is the reason, my dear

Thrasymachus, why, as I was just now saying, no one is

willing to govern; because no one likes to take in hand the

reformation of evils which are not his concern without

[347] remuneration. For, in the execution of his work, and in

giving his orders to another, the true artist does not regard

his own interest, but always that of his subjects; and

therefore in order that rulers may be willing to rule, they must be

paid in one of three modes of payment, money, or honour, or

a penalty for refusing. (1888:23-25)

7.533a-c

Only the science of dialectic goes directly to the first principle, while art not (being dependent on the senses).

| Edition: Adam 1903. Translations: Jowett 1871/88 EN, Grube/Reeve 1974/97 EN, Badiou/Spitzer 2013 EN. |

Jowett

And assuredly no one will argue [533b] that there is any other

method of comprehending [other than dialectic] by any regular process all true

existence or of ascertaining what each thing is in its own

nature; for the arts in general are concerned with the

desires or opinions of men, or are cultivated with a view to

production and construction, or for the preservation of such

productions and constructions; and as to the mathematical

sciences which, as we were saying, have some apprehension

of true being--geometry and the like--[533c] they only dream about

being, but never can they behold the waking reality so long

as they leave the hypotheses which they use unexamined, and

are unable to give an account of them. For when a man

knows not his own first principle, and when the conclusion

and intermediate steps are also constructed out of he knows

not what, how can he imagine that such a fabric of

convention can ever become science ?

Impossible, he said. (1888:236-7)

Manuscripts

Primary manuscripts

- Parisinus graecus 1807 [A], 9th c., Gallica. Both A1 and A2 are identical with the scribe; A2 indicates the readings he added after the whole text had been written, as can be seen from the different colour of the ink. Kept at Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. For more, see Boter 1989:81-6.

- Venetus Marcianus graecus 185 [D] (numero di collocazione 576), 12th c. For more, see Boter 1989:92-4 and Slings 2005:154. Parts are absent (507e3–515d7 and 612e8–621d5).

- Vindobonensis suppl. gr. 39 [F], 13-14th c. For more, see Boter 1989:101-4.

Sourced from Slings 2005:195.

Secondary manuscripts

- Bononiensis 3630, 13-14th c. (Bon). A gemellus of Vind.phil.gr. 89, deriving from Dac.

- Caesenas D 28,4 (Malatestianus), 15th c. (M). A gemellus of Laur.CS.42 (see below), deriving from A.

- Laurentianus 80.7, 15th c. (α). A heavily contaminated MS, deriving indirectly from Laur.CS.42 (see below).

- Laurentianus 80.19, 14-15th c. (β). An indirect copy of Parisinus gr. 1810 (see below), corrected (sometimes from its exemplar) by a highly intelligent scribe (see Boter 1989:203-14).

- Laurentianus 85.7, 15th c. (x). A copy of F.

- Laurentianus Conventi Soppressi 42, 12-13th c. (γ). A gemellus of Caes.D.28.4 (see above), deriving from A.

- Monacensis graecus 237, 15th c. (q). A copy of Laur.80.19 (see above).

- Parisinus graecus 1642, 14th c. (K). A gemellus of Laur.80.19 (see above) in books I–III.

- Parisinus graecus 1810, 14th c. (Par). Derives from D as corrected by D2 and D3.

- Pragensis Radnice VI.F.a.1 (Lobc[ovicianus]), 14-15th c.. Derives from Scor. y.1.13 (see below).

- Scorialensis y.1.13, 13-14th c. (Sc). Derives from Ven.Marc.App.Cl. IV,1 up to 389d7, from Dac from 389d7 on.

- Scorialensis Ψ.1.1, dated 1462 (Ψ). Derives from D as corrected by D2 and D3.

- Vaticanus graecus 229, 14th c.. An indirect copy of Parisinus gr. 1810 (see above).

- Venetus Marcianus gr. 184 (coll. 326), c1450 (E); written by Johannes Rhosus for Bessarion. A direct copy of Marc.187.

- Venetus Marcianus gr. 187 (coll. 742), c1450 (N). An indirect copy of Venetus Marcianus App. Cl. IV,1 (T) in books I–II; an indirect copy of Laur.85.9 (which derives from A) in books III–X. Written for, and heavily corrected by, Bessarion.

- Venetus Marcianus App. Cl. IV,1 (coll. 542), c950 (up to 389d7), s. xv (the remainder) (T). A, indirect copy of A until 389d7; an indirect copy of Dac after 389d7.

- Vindobonensis phil. gr. 1, 16th c. (V). An indirect copy of Laur.85.9, which derives from A.

- Vindobonensis phil. gr. 89, c1500 (Vind). A gemellus of Bonon.3630, deriving from Dac.

- Vindobonensis suppl. gr. 7, 14th c. (the part containing R.) (W). An indirect copy of D.

Sourced from Slings 2005:195-6.

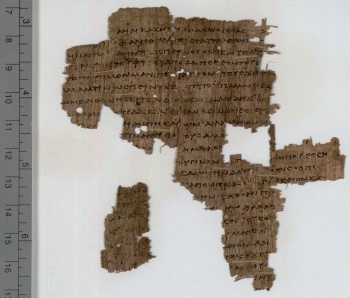

Papyri

- P.Oxy. 3509 [Π1], third century CE, Image. Contains fragments from 330a2–b4; many gaps at the beginning of the lines.

- P.Flor. inv. 1994 [Π2], second-third century CE. Contains fragments from 399d10–e3; only the ends of the lines are preserved.

- P.Oxy. 455 [Π3], third century CE. Contains fragments from 406a5–b4; some gaps at the beginnings of the lines. [3]

- P.Oxy. 2751 [Π4], late second or early third century CE, Image. Contains fragments from 412c–414b; many gaps.

- P.Oxy. 456 [Π5], late second or early third century CE. Contains fragments from 422c8–d2; gaps at the beginnings and ends of the lines. [4]

- P.Oxy. 3679 [Π6], third century CE, Image. Contains fragments from 472e4–473a5, some gaps; and 473d1–d5, only the beginnings of the lines are preserved.

- PRIMI I 10 [Π7], third century CE. Contains fragments from 485c10–d6 and 486b10–c3; gaps at the beginnings and ends of the lines.

- P.Oxy. 3326 [Π8], second century CE, Image. Contains fragments from 545c1–546a3; parts missing.

- P.Oxy. 1808 [Π9], late second century CE, Image. Contains fragments from 546b–547d; some corrections in a later hand; some gaps.

- P.Oxy. 24 [Π10], third century CE. Contains fragments from 607e4–608a1; some gaps. [5]

- P.Oxy. 3157 [Π11], second century CE, Images. Contains fragments from 610c7–611a7, 611c5–d2, 611e1–612c7 and 613a1–7; many gaps at the beginnings and ends of the lines.

Sourced from Boter 1989:252-7 (see for more details), which also establishes the Π sygla, Google.

Editions, commentaries

- Aldus Manutius, and Marcus Musurus, "Politeion", Omnia Platonis opera, [Venice]: Aldus, 1513, BSB. Editio princeps.

- Oporinus, Johannes, and Simon Grynaeus, Platonis Omnia Opera Cum Commentariis Procli in Timaeum & Politica, thesauro veteris Philosophiae maximo, Basle [Basel]: Johannes Walder, 1534. Also contains a commentary of Proclus on the Republic. [6]

- Stephanus, Henricus, Platonis opera quae exstant omnia, [Geneva], 1578.

- Fr. Ast, Platonis Politia sive de Republica libri decem, Ienae [Jena], 1804; Ienae [Jena], 1820; 2nd ed., Lipsiae [Leipzig], 1814; 3rd ed. as Platonis quae exstant opera, IV–V, Lipsiae [Leipzig], 1822.

- Bekker, I., Platonis dialogi, III 1, Berolini [Berlin], 1817. Critical notes in Commentaria critica in Platonem a se editum, Berolini [Berlin], 1823.

- Stallbaum, G., Platonis quae supersunt opera, Leipzig, 1821-25 (R. 1823).

- Stallbaum, G., Platonis dialogos selectos, III, 1–2, Gothae [Gotha] and Erfordiae [Erfurt], 1829-30.

- Schneider, C.E.C., Platonis opera Graece, Lipsiae [Leipzig], 1830-33. Supplemented by his Additamenta ad Civitatis Platonis libros X, Lipsiae [Leipzig], 1854.

- Baiter, J.G., J.C. Orelli, and A.W. Winckelmann, Platonis opera omnia, XIII, 1840; Turici [Zürich], 1874; Londini [London], 1881.

- Hermann, Karl Friedrich, Platonis dialogi, IV, Leipzig: Teubner, 1852; Platonis: Rei Publicae libri decem, Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Teubner, 1880, IA.

- Jowett, Benjamin, and Lewis Campbell, Plato's Republic: The Greek Text. Edited, with Notes and Essays in Three Volumes. Vol I. Text, Vol III. Notes, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894, IA, IA, 3.

- Adam, James, The Republic of Plato, edited, with critical notes, commentary, and appendices, University Press, 1897, IA; 1899; 1900, IA, 1900, IA, IA; 1902, IA, vol 1; repr. in Platonis Opera, ed. John Burnet, 1903, Perseus; 1905, IA/1; 1907, IA/2; 1921, IA, vol. 2; 1929, IA/2; 2nd ed., 2 vols., co-ed. D.A. Rees, Cambridge University Press, 1963; 1965; 1969; 1975; 1980; 2010.

- Tucker, T.G., The Proem to the Ideal Commonwealth of Plato [Books I–II 368c], London: George Bell, 1900, IA.

- Burnet, John, "Republic", in Platonis Opera, IV, Oxford University Press, 1903, Perseus.

- Shorey, P., Plato, the Republic, London and Cambridge/MA: Loeb, 1930-35.

- Chambry, Émile, Platon, Oeuvres complètes, VI–VII, Paris: Budé, 1932-34. The first editor who could make use of papyri; four of them were known at the time.

- Allan, D.J., Plato’s Republic, Book I, London, 1955.

- Slings, S.R., Platonis Rempublicam, Oxford: Oxford Classical Texts, 2003. The critical notes supporting Slings’ edition have been collected as Slings, S.R., Critical Notes on Plato’s Politeia, eds. Gerard Boter and Jan van Ophuijsen, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005, PDF.

Translations

| The languages are ordered according to their earliest translation. The links following respective editions point to their online versions; where no file format is specified abbreviations stand for digital archives. Links within the wiki are in green. More languages will follow. |

Medieval Latin

- Chrysoloras, Manuel, and Uberto Decembrio, 1403. Made in a close collaboration of Chrysoloras with his pupil Uberto in the years 1400-03. (Boter 1989:261-4)

- Pier Candido Decembrio, 1441. Made by Uberto's son between 1437 and 1441; reworking of the Chrysoloras-Uberto translation. (Boter 1989:265-8)

- Cassarino, Antonio, 1447. Made in the years 1438-47. (Boter 1989:268-70)

- Ficino, Marsilio, 1484. Ficino relied at first on Latin translations of Plato; he studied Greek beginning in 1458-59 and in 1462 Cosimo the Elder and Amerigo Benci gave Ficino the gift of a Platonic Codex that Ficino began to translate into Latin. (Garin, Commentaries on Plato, 1, 2008:xxii; Boter 1989:270-8)

For a survey of the 15th-century Latin translations of the Republic, see Eugenio Garin, "Richerche sulle traduzioni di Platone nella prima metà del sec. XV", in Medioevo e rinascimento. Studi in onore di Bruno Nardi, I., Florence, 1955, pp 339-374; Paul Oskar Kristeller, "The first printed edition of Plato’s works and the date of its publication (1484)", in Science and History. Studies in Honour of Edward Rosen, 1978, pp 25-35; and Boter 1989:261-78, [7].

French

- Grou, Jean Nicolas, La Republique de Platon ou Dialogue sur la justice], 2 vols., Paris: Brocas & Humblot, 1762, IA/1, IA/1, IA/2.

- La République de Platon, 2 vols., Dresde [Dresden]: Les frères Walther, 1787, BSB/1, BSB/1, BSB/2.

- Baccou, Robert, "La République. Traduction nouvelle avec introduction et notes", in Platon, Oeuvres complètes, tome 4, Paris: Garnier Frères, 1945.

- Chambry, Émile, Platon: République, intro. Auguste Dies, Gonthier, 1963, 366 pp.

- Leroux, G., Platon: La République, Paris, 2002.

- Badiou, Alain, La République de Platon, Fayard, 2012.

English

- Spens, H., The Republic of Plato in Ten Books, Glasgow: Robert and Andrew Foulis, 1763, IA; new ed., intro. Richard Garnett, London and Toronto: J.M. Dent, and New York: E.P. Dutton, 1906, IA.

- Sydenham, Floyer, and Thomas Taylor, "The Republic", in The Works of Plato, Vol. 1, London, 1804, IA.

- Davies, John Llewelyn, and David James Vaughan, The Republic of Plato. Translated into English, with an Analysis, and Notes, 1852, Google; 2nd ed., 1858; 1860; 3rd ed., Cambridge and London: Macmillan, 1866; 2 Vols, 1898; 1921, IA; London: Macmillan, 1927. [8] [9]

- Burges, George, Plato: The Republic, Timaeus and Critias. New and literal version, London: H.G. Bohn, 1854.

- Jowett, Benjamin, The Republic of Plato. Translated into English with Introduction, Analysis, Marginal Analysis and Index, 1871; 3rd ed., 1888, IA; rev. ed., Colonial Press, 1901, IA; 1907, IA; Roslyn, New York: Walter J. Black, 1942, OL; Vintage, 1955, OL; Doubleday, 1960, OL; 2008, PG. Repr. as "The Republic", in The Dialogues of Plato, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1952, OL.

- Wells, G.H., The Republic of Plato. Books I. and II. With an Introduction, Notes, and the Argument of the Dialogue, London: George Bell, 1882, IA; repr. 1888, IA.

- Warren, T. Herbert, The Republic of Plato. Books I.-V. With Introduction and Notes, London: Macmillan, 1892, IA; repr. 1901, IA.

- Taylor, Thomas, The Republic of Plato, ed. Theodore Wratislaw, London: Walter Scott, 1894, IA.

- Bosanquet, Bernard, The Education of the Young in The Republic of Plato. Translated into English with Notes and Introduction, Cambridge: University Press, 1900, IA; repr. 1908, IA. Trans. of Book II (366 to end), Book III, and Book IV.

- Davis, Henry, "Plato: The Republic", in The Republic. The Statesman, New York and London: M. Walter Dunne, 1901.

- Lindsay, A.D., Plato: The Republic, London: J.M. Dent, 1906; 3rd ed. with Revised Text and Enlarged Introduction, 1923, IA; New York: Dutton, 1957, OL; intro. A. Nehamas, notes R. Bambrough, New York, 1992.

- Sydenham, Floyer, and Thomas Taylor, The Republic of Plato, rev. by W.H.D. Rouse, intro. Ernest Barker, London: Methuen, 1906, IA.

- Kerr, Alexander, Book III, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 1903, IA; Book VI, 1909, IA; The Republic of Plato. Book VII, 1911, IA; Book VIII, 1914, IA.

- Shorey, Paul, Plato: Republic. Edited, translated, with notes and an introduction, London: W. Heinemann, 1930; repr. as Plato: The Republic. With an English Translation in Two Volumes, I: Books I-V, and II, Harvard University Press, and London: Heinemann, 1937, IA/1. Loeb Classical Library. [text, tr.]

- Cornford, Francis MacDonald, The Republic of Plato. Translated with Introdution and Notes, Oxford University Press, 2 vols., 1941; 1945, OL; 1951, 400 pp; 1964, 366 pp; 1972; 1981.

- Lee, Desmond, Plato: The Republic. Translated with an Introduction, Penguin, 1955; 2nd ed., 1974, OL; 1987; 2003, with a new bibliography by R. Kamtekar.

- Rouse, W.H.D., "The Republic", in Great Dialogues of Plato, eds. Eric H. Warmington and Philip G. Rouse, New York and Toronto: New American Library, 1956, OL; 2008.

- Bloom, Allan, The Republic of Plato. Translated, with notes and an interpretive essay, New York: Basic Books, 1968; 2nd ed., 1991, ARG, PDF. Contains long interpretive essay.

- Shorey, Paul, Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 5 & 6, Harvard University Press, and London: W. Heinemann, 1969, Perseus.

- Grube, G.M.A., Plato: The Republic, Indianapolis: Hackett, 1974, OL; rev. by C.D.C. Reeve, 1992; repr. in Plato: Complete Works, ed. J. Cooper, Indianapolis, 1997.

- Larson, Raymond, Plato: The Republic, intro. Eva T.H. Brann, Wheeling: Harlan Davidson, 1979.

- Sterling, Richard W., and William C. Scott, Plato: The Republic: A New Translation, London: Norton, 1985, 320 pp; 1996.

- Waterfield, Robin, Plato: Republic. Translated, with notes and an introduction, Oxford: Oxford World's Classics, 1993.

- Blair, George A., Plato's Republic for Readers: A Constitution, University Press of America, 1998, 440 pp.

- Griffith, Tom, Plato: The Republic, ed. G. R. F. Ferrari, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Reeve, C.D.C., Plato: The Republic. Translated from the New Standard Greek Text, with Introduction, Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004, ARG. Based on 2003 Slings edition.

- Allen, R.E., Plato: The Republic, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Sachs, Joe, Plato: Republic, Newburyport: Focus, 2007.

- Tschemplik, Andrea, The Republic: The Comprehensive Student Edition, 2006.

- Emlyn-Jones, Chris, and William Preddy, Plato V: Republic, Volume I. Books 1-5 and Plato VI: Republic, Volume II. Books 6-10, Harvard University Press, 2013, 567 and 503 pp. Loeb Classical Library edition. Review.

- Spitzer, Susan, Plato's Republic: A Dialogue in 16 Chapters, intro. Kenneth Reinhard, Polity Press, 2013, 400 pp, ARG. English translation of a translation by Alain Badiou.

- More.

Dutch

- D. D. Burger, De Republiek van Plato, Amsterdam: P.N. van Kampen, 1849, IA.

German

- Teuffel, Wilhelm Sigismund, and Wilhelm Wiegand, Platon's Werke. Zehn Bücher vom Staate, 2 vols., Stuttgart, 1855/56, HTML, HTML; 8th ed.; repr. as "Der Staat", in Platon: Sämtliche Werke in drei Bänden, vol. 2, ed. Erich Loewenthal, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2004, pp 5-407.

- Schleiermacher, Friedrich, Plato's Staat, notes J.H. v. Kirchmann, Berlin: Heimann, 1870, IA.

- Apelt, Otto, Platon: Der Staat, 3rd ed., Leipzig, 1923; repr. in Platon: Sämtliche Dialoge, vol. 5, ed. Otto Apelt, Hamburg: Meiner, 2004.

- Horneffer, August, Platon: Der Staat, Stuttgart: Kröner, 1955.

- Vretska, Karl, Platon: Der Staat, 1982; repr., Stuttgart: Reclam, 2004.

Czech

- Peroutka, Emanuel. [unfinished]

- Novotný, František, Platón: Ústava. S užitím překladu Emanuele Peroutky, Prague: Jan Laichter, 1921, 402 pp, IA, HTML; 2nd ed., Prague, 1996; 3rd ed., Prague: Oikoymenh, 2001, PDFs; 4th ed., 2005, 428 pp; 5th ed., 2014, 428 pp.

- Hošek, Radislav, Platón: Ústava, Prague: Svoboda-Libertas, 1993, 524 pp.

Modern Greek

- Papatheodorou, A. (Α. Παπαθεοδώρου), F. Pappas (Φιλ. Παππά), and Alexandros Galinos (Αλέξανδρος Γαληνού), Πλάτωνος. Πολιτεία. Ή περί δικαίου πολιτικός, intro. Adamantios Diamandopoulos, 2 vols., Athens: Papyros Editions, 1936; Papyros Academic Society of Greek Letters (Πάπυρος Εκδοτικός Οργανισμός), 1975, 640 pp. Books I-V trans., comm. and annot. by Papatheodorou and Pappas, Books VI-X by Galinos. (Fragkou 2012:82-6) [10]

- Skouteropoulos, Ioannis (Ιωάννης Σκουτερόπουλος), Athens: Andreas Sideris, 1948; new ed., exp., 1962. (Fragkou 2012:87-93)

- Georgoulis, Konstantinos (Κωνσταντίνος Γεωργούλη), Πλάτωνος. Πολιτεία. Ή περί δικαίου πολιτικός, 1939; Φεβρουάριος, 2009, 592 pp. [tr., comm.]. Canonical translation (along with the ones by Georgoulis and N. Skouteropoulos). (Fragkou 2012:99-100)

- Gryparis, Ioannis (Ιωάννης Γρυπάρης), and Evangelos Papanoutsos (Ευάγγελος Παπανούτσος), Πλάτων. Πολιτεία, intro. Evangelos Papanoutsos, Athens: Zaharopoulos (Ζαχαρόπουλος), c1945, HTML; repr., Chalandri: 4π Ειδικές Εκδόσεις, 2011. [tr., comm.] The most poetic rendition of the retranslations of the Republic; written in demotiki (the people’s natural language); one of the two or three canonical translations (the others being Georgoulis’ and N. Skouteropoulos’ ones). Reworking of his 1911 translation written in katharevoussa and published by Phexis Editions; Gryparis died in 1942 before being able to finish the work; Books VII to X were subsequently transliterated into demotiki by Papanoutsos using Gryparis' katharevoussa version. (Fragkou 2012:94-8)

- Hatzopoulos, Odysseas, Πλάτων. Πολιτεία, 5 vols., Athens: Kaktos (Κάκτος), 1992. [text, tr.] (Fragkou 2012:101-3)

- Memmos, Nikolaos (Νικολαος Μεμμος), Η Πολιτεία του Πλάτωνα, Thessaloniki: Pournaras, 1994, 786 pp. (Fragkou 2012:104-5)

- Mavropoulos, Theodoros (Θεόδωρος Γ. Μαυρόπουλος), Πλάτων. Πολιτεία, 2 vols., Thessaloniki: Zitros (Ζήτρος), 2006, 1611 pp. [tr., comm.] (Fragkou 2012:106-8) [11] [12]

- Nikolaos Skouteropoulos (Νικολαος Μ. Σκουτερόπουλος), Πλάτων. Πολιτεία, Athens: Polis (Πόλις), 2002, HTML. [tr., comm.]. Standard translation (along with the ones by Georgoulis and Gryparis). (Fragkou 2012:109-11)

Italian

- Sartori, Franco, Platone: La Repubblica, 1966; new ed., intro. Mario Vegetti, notes Bruno Centrone, Rome: Laterza, 1997; Rome: Laterza, 2011.

- Adorno, F., "Platone, La Repubblica", in Tutti i dialoghi, Turin: Utet, 1988.

- Lozza, G., Platone, La Repubblica, Milan: Mondadori, 1990.

- Vegetti, Mario, Platone, La Repubblica, 7 vols., Naples: Bibliopolis, 1998-2007.

- Albertella, Marta, Alain Badiou. La Repubblica di Platone, intro. Livio Boni, Milan: Adriano Salani, 2013, EPUB.

Portuguese

- Nunes, Carlos Alberto, A República - Platão, 1973; 2nd ed., 1988; 3rd ed., Belem: EDUFPA, 2000, PDF.

- Pereira, Maria Helena da Rocha, A República - Platão, Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian, 9th ed., 2001, PDF. [tr., notes]

- Telles, André, A República de Platão. Recontada Por Alain Badiou, Zahar, 2014, EPUB.

Lithuanian

Spanish

- Lan, Conrado Eggers, Platón. Dialógos IV: República, Madrid: Gredos, 1986; 1988, PDF, Scribd. [tr., notes]

Romanian

- Cornea, Andrei, "Republica", in Platon, Opere V, Bucharest: Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică, 1986, IA; 2nd ed., Bucharest: Teora, 1998. [tr., comm.]

Studies

| This section is to be expanded. |

- Jowett, Benjamin, and Lewis Campbell, Plato's Republic: The Greek Text. Edited, with Notes and Essays in Three Volumes. Vol II. Essays, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894, IA, IA.

- Bosanquet, Bernard, A Companion to Plato's Republic for English Readers. Being a Commentary adapted to Davies and Vaughan's Translation, New York: Macmillan, 1895, IA.

- Adam, Joseph, The Republic of Plato, Cambridge, 1902.

- Cross, R.C., and Woozley, A.D., Plato's Republic. A Philosophical Commentary, London, 1964. A detailed commentary, with special emphasis on logic and politics.

- Boter, Gerard, The Textual Tradition of Plato’s Republic, Leiden, 1989. Revised Ph.D. dissertation, Free University, Amsterdam, 1986. On the transmission history of the text. [15]

- Brown, Eric, "Plato's Ethics and Politics in The Republic", in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2003; 2009, HTML.

- Ferrari, G.R.F. (ed.), Cambridge Companion to Plato's Republic, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Fragkou, Effrossyni, Retranslating Philosophy: The Role of Plato’s Republic in Shaping and Understanding Politics and Philosophy in Modern Greece, Ottawa: University of Ottawa, 2012, 335 pp, PDF. Ph.D. Dissertation.

- Plato's Republic entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

See also bibliographies in Slings 2005:197-9 and Ferrari 2007:477-510.

Bibliographies online

- Bibliography of translations, commentaries and editions of Plato's Republic

- The Platonic Textual Tradition: A Bibliography, compiled by Mark Joyal, U Manitoba.