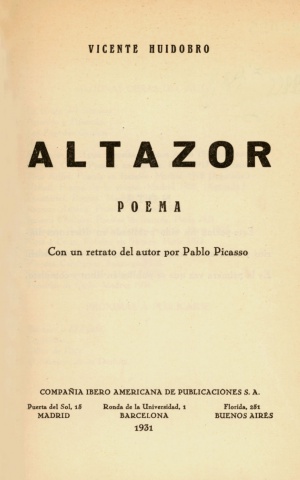

Vicente Huidobro: Altazor, or, A Voyage in a Parachute/1919, a Poem in VII Cantos (1931–) [ES, EN]

Filed under fiction | Tags: · poetry

“The first modern poet of the Spanish language — in many ways its Apollinaire — Vicente Huidobro is generally considered to be one of the four greatest Spanish American poets of [the last] century. Yet unlike his peers — César Vallejo, Pablo Neruda, and Octavio Paz — Huidobro is still little-known in the English-speaking world.

Altazor, a book-length poem first published in 1931, is Huidobro’s masterpiece and one of the wildest poems of any language. The century’s great paean to flight, the poem sends its hero (Altazor, the antipoet) hurtling through Einsteinian space at light-speed, as all places and times collapse into one.” (from the back cover)

Publisher Compañia Ibero Americana de Publicaciones, Madrid/Barcelona/Buenos Aires, 1931

111 pages

Bilingual Spanish/English edition

Translated by Eliot Weinberger

Publisher Graywolf Press, Saint Paul, Minnesota, 1988

A Palabra Sur Book

ISBN 1555971067

167 pages

via filboid

Commentary: MemoriaChilena (ES), Justin Read (Translation Review, 2006, pp 61-65, EN), Mario Nandayapa (Liminar, 2006, ES), Bruce Dean Willis (Hispanic Issues, 2010, EN), Comparative analysis with Beckett’s Imagination Dead Imagine (Margaret Lees McTague, Master’s Thesis, 1976, EN).

PDF, PDF, HTML (Spanish, 1931, updated on 2020-12-6)

PDF (Spanish/English, 1988)

PDF, PDF (manuscript, Spanish)

Audio books (Spanish)

See also Altazor: de puño y letra (Spanish, ed. & with notes by Andrés Morales, 1999)

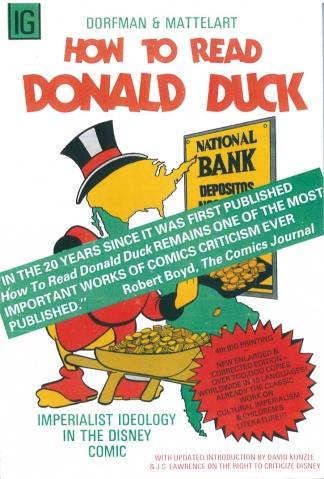

Ariel Dorfman, Armand Mattelart: How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic (1972–) [ES, IT, EN, PT, TR]

Filed under book | Tags: · capitalism, colonialism, comics, cultural criticism, entertainment, ideology, literary criticism, marxism, political theory, politics

How to Read Donald Duck is a Marxist political analysis by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart on what they perceive is cultural imperialism in popular entertainment, published in Chile in 1972. Written in the form of essay (or, in the authors’ words, a “decolonization manual”), the book is an analysis of mass literature, specifically the Disney comics published for the Latin American market. It is one of the first social studies of entertainment and the leisure industry from a political-ideological angle, and the book deals extensively with the political role of children’s literature. (from Wikipedia)

First published by Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, Chile, 1972

First published in English in 1975

Translated and with an Introduction by David Kunzle

With Appendix by John Shelton Lawrence

Publisher International General, New York, 1991 (Fourth printing)

ISBN 0884770370

119 pages

via Quaxo Coricopat

An interview with Mattelart in which he shortly discusses the book (2008, in English)

2012 project for appropriation of the book (includes its online edition)

Para leer al Pato Donald. Comunicación de masa y colonialismo (Spanish, 18th ed., 1972/1979)

Come leggere Paperino. Ideologia e politica nel mondo di Disney (Italian, trans. Gianni Guadalupi, 1972, added on 2023-7-31)

How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic (English, trans. David Kunzle, 1975/1991, 10 MB, updated 2015-5-10)

Para ler o Pato Donald: comunicação de massa e colonialismo (Portuguese, trans. Álvaro de Moya, 2nd ed., 1976/1980)

Emperyalist Kültür Sanayii ve Walt Disney: Vakvak Amca Nasıl Okunmalı? (Turkish, trans. Atilla Aksoy, 1977)

Le concept d’information dans la science contemporaine (1965) [French]

Filed under proceedings | Tags: · communication, computing, cybernetics, information, information theory, machine, mathematics, philosophy, science

“The proceedings from the Sixth Symposium at Royaumont in 1962 were titled Le concept d’information dans la science contemporaine [The Concept of Information in Contemporary Science] and were published three years later in Paris by Les Éditions de Minuit.

In attendance were Gilbert Simondon, Norbert Wiener, Martial Gueroult, Giorgio de Santillana, Lucien Goldmann, Benoit Mandelbrot, René de Possel, Jean Hyppolite, André Michel Lwoff, Abraham Moles, Ferdinand Alquié, Henryk Greniewski, Helmar Frank, Jiri Zeman, François Bonsack, Louis Couffignal, Albert Perez, Maurice de Gandillac, Ladislav Tondl, Gilles-Gaston Granger, and Stanislas Bellert, among others.

Simondon was a very active organizer and introduced Wiener. The collection is fascinating for a number of reasons; most striking, perhaps, is the fact that a prominent Marxist (Goldmann) and a brilliant mathematician (Mandelbrot) were given equal opportunity to talk philosophically about the concept of information. Mathematicians like Mandelbrot and Wiener were given the same stage as philosophers like Simondon and Hyppolite.

Some of the papers are pretty scientific, but most of them are not. What you get is a collection of papers given and discussed (the Q & As are included and are revealing) by some of the individuals who heavily influenced Deleuze and a number of other French philosophers. This is an incredibly revealing volume and I will eventually work hard to translate some of the papers that are included.

Simondon’s paper, ‘L’Amplification dans les processus d’information’, was not included in the proceedings (only the abstract is provided at the very end of the book, along with the topic of Wiener’s response to Simondon), but was published and is available in the collection of his papers titled Communication and Information: Courses and Conferences (La Transparence, 2010).” (from a blog post by Andrew Iliadis)

Publisher Les Éditions de Minuit, Paris, 1965

425 pages

via Andrew Iliadis, HT babyalanturing

Review: D. Gabor (The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 1966, EN).

PDF (36 MB, updated on 2021-3-28)

multiple formats (Internet Archive)