_A talk given on the second day of the conference_ [Off the

Press](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/22-23-may-2014/program/) _held at

WORM, Rotterdam, on May 23, 2014. Also available

in[PDF](/images/2/28/Barok_2014_Communing_Texts.pdf "Barok 2014 Communing

Texts.pdf")._

I am going to talk about publishing in the humanities, including scanning

culture, and its unrealised potentials online. For this I will treat the

internet not only as a platform for storage and distribution but also as a

medium with its own specific means for reading and writing, and consider the

relevance of plain text and its various rendering formats, such as HTML, XML,

markdown, wikitext and TeX.

One of the main reasons why books today are downloaded and bookmarked but

hardly read is the fact that they may contain something relevant but they

begin at the beginning and end at the end; or at least we are used to treat

them in this way. E-book readers and browsers are equipped with fulltext

search functionality but the search for "how does the internet change the way

we read" doesn't yield anything interesting but the diversion of attention.

Whilst there are dozens of books written on this issue. When being insistent,

one easily ends up with a folder with dozens of other books, stucked with how

to read them. There is a plethora of books online, yet there are indeed mostly

machines reading them.

It is surely tempting to celebrate or to despise the age of artificial

intelligence, flat ontology and narrowing down the differences between humans

and machines, and to write books as if only for machines or return to the

analogue, but we may as well look back and reconsider the beauty of simple

linear reading of the age of print, not for nostalgia but for what we can

learn from it.

This perspective implies treating texts in their context, and particularly in

the way they commute, how they are brought in relations with one another, into

a community, by the mere act of writing, through a technique that have

developed over time into what we have came to call _referencing_. While in the

early days referring to texts was practised simply as verbal description of a

referred writing, over millenia it evolved into a technique with standardised

practices and styles, and accordingly: it gained _precision_. This precision

is however nothing machinic, since referring to particular passages in other

texts instead of texts as wholes is an act of comradeship because it spares

the reader time when locating the passage. It also makes apparent that it is

through contexts that the web of printed books has been woven. But even though

referencing in its precision has been meant to be very concrete, particularly

the advent of the web made apparent that it is instead _virtual_. And for the

reader, laborous to follow. The web has shown and taught us that a reference

from one document to another can be plastic. To follow a reference from a

printed book the reader has to stand up, walk down the street to a library,

pick up the referred volume, flip through its pages until the referred one is

found and then follow the text until the passage most probably implied in the

text is identified, while on the web the reader, _ideally_ , merely moves her

finger a few milimeters. To click or tap; the difference between the long way

and the short way is obviously the hyperlink. Of course, in the absence of the

short way, even scholars are used to follow the reference the long way only as

an exception: there was established an unwritten rule to write for readers who

are familiar with literature in the respective field (what in turn reproduces

disciplinarity of the reader and writer), while in the case of unfamiliarity

with referred passage the reader inducts its content by interpreting its

interpretation of the writer. The beauty of reading across references was

never fully realised. But now our question is, can we be so certain that this

practice is still necessary today?

The web silently brought about a way to _implement_ the plasticity of this

pointing although it has not been realised as the legacy of referencing as we

know it from print. Today, when linking a text and having a particular passage

in mind, and even describing it in detail, the majority of links physically

point merely to the beginning of the text. Hyperlinks are linking documents as

wholes by default and the use of anchors in texts has been hardly thought of

as a _requirement_ to enable precise linking.

If we look at popular online journalism and its use of hyperlinks within the

text body we may claim that rarely someone can afford to read all those linked

articles, not even talking about hundreds of pages long reports and the like

and if something is wrong, it would get corrected via comments anyway. On the

internet, the writer is meant to be in more immediate feedback with the

reader. But not always readers are keen to comment and not always they are

allowed to. We may be easily driven to forget that quoting half of the

sentence is never quoting a full sentence, and if there ought to be the entire

quote, its source text in its whole length would need to be quoted. Think of

the quote _information wants to be free_ , which is rarely quoted with its

wider context taken into account. Even factoids, numbers, can be carbon-quoted

but if taken out of the context their meaning can be shaped significantly. The

reason for aversion to follow a reference may well be that we are usually

pointed to begin reading another text from its beginning.

While this is exactly where the practices of linking as on the web and

referencing as in scholarly work may benefit from one another. The question is

_how_ to bring them closer together.

An approach I am going to propose requires a conceptual leap to something we

have not been taught.

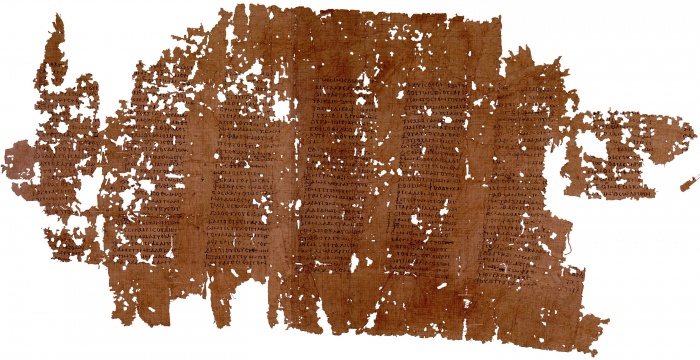

For centuries, the primary format of the text has been the page, a vessel, a

medium, a frame containing text embedded between straight, less or more

explicit, horizontal and vertical borders. Even before the material of the

page such as papyrus and paper appeared, the text was already contained in

lines and columns, a structure which we have learnt to perceive as a grid. The

idea of the grid allows us to view text as being structured in lines and

pages, that are in turn in hand if something is to be referred to. Pages are

counted as the distance from the beginning of the book, and lines as the

distance from the beginning of the page. It is not surprising because it is in

accord with inherent quality of its material medium -- a sheet of paper has a

shape which in turn shapes a body of a text. This tradition goes as far as to

the Ancient times and the bookroll in which we indeed find textual grids.

[](/File:Papyrus_of_Plato_Phaedrus.jpg)

A crucial difference between print and digital is that text files such as HTML

documents nor markdown documents nor database-driven texts did inherit this

quality. Their containers are simply not structured into pages, precisely

because of the nature of their materiality as media. Files are written on

memory drives in scattered chunks, beginning at point A and ending at point B

of a drive, continuing from C until D, and so on. Where does each of these

chunks start is ultimately independent from what it contains.

Forensic archaeologists would confirm that when a portion of a text survives,

in the case of ASCII documents it is not a page here and page there, or the

first half of the book, but textual blocks from completely arbitrary places of

the document.

This may sound unrelated to how we, humans, structure our writing in HTML

documents, emails, Office documents, even computer code, but it is a reminder

that we structure them for habitual (interfaces are rectangular) and cultural

(human-readability) reasons rather then for a technical necessity that would

stem from material properties of the medium. This distinction is apparent for

example in HTML, XML, wikitext and TeX documents with their content being both

stored on the physical drive and treated when rendered for reading interfaces

as single flow of text, and the same goes for other texts when treated with

automatic line-break setting turned off. Because line-breaks and spaces and

everything else is merely a number corresponding to a symbol in character set.

So how to address a section in this kind of document? An option offers itself

-- how computers do, or rather how we made them do it -- as a position of the

beginning of the section in the array, in one long line. It would mean to

treat the text document not in its grid-like format but as line, which merely

adapts to properties of its display when rendered. As it is nicely implied in

the animated logo of this event and as we know it from EPUBs for example.

In the case of 'reference-linking' we can refer to a passage by including the

information about its beginning and length determined by the character

position within the text (in analogy to _pp._ operator used for printed

publications) as well as the text version information (in printed texts served

by edition and date of publication). So what is common in printed text as the

page information is here replaced by the character position range and version.

Such a reference-link is more precise while addressing particular section of a

particular version of a document regardless of how it is rendered on an

interface.

It is a relatively simple idea and its implementation does not be seem to be

very hard, although I wonder why it has not been implemented already. I

discussed it with several people yesterday to find out there were indeed

already attempts in this direction. Adam Hyde pointed me to a proposal for

_fuzzy anchors_ presented on the blog of the Hypothes.is initiative last year,

which in order to overcome the need for versioning employs diff algorithms to

locate the referred section, although it is too complicated to be explained in

this setting.[1] Aaaarg has recently implemented in its PDF reader an option

to generate URLs for a particular point in the scanned document which itself

is a great improvement although it treats texts as images, thus being specific

to a particular scan of a book, and generated links are not public URLs.

Using the character position in references requires an agreement on how to

count. There are at least two options. One is to include all source code in

positioning, which means measuring the distance from the anchor such as the

beginning of the text, the beginning of the chapter, or the beginning of the

paragraph. The second option is to make a distinction between operators and

operands, and count only in operands. Here there are further options where to

make the line between them. We can consider as operands only characters with

phonetic properties -- letters, numbers and symbols, stripping the text from

operators that are there to shape sonic and visual rendering of the text such

as whitespaces, commas, periods, HTML and markdown and other tags so that we

are left with the body of the text to count in. This would mean to render

operators unreferrable and count as in _scriptio continua_.

_Scriptio continua_ is a very old example of the linear onedimensional

treatment of the text. Let's look again at the bookroll with Plato's writing.

Even though it is 'designed' into grids on a closer look it reveals the lack

of any other structural elements -- there are no spaces, commas, periods or

line-breaks, the text is merely one flow, one long line.

_Phaedrus_ was written in the fourth century BC (this copy comes from the

second century AD). Word and paragraph separators were reintroduced much

later, between the second and sixth century AD when rolls were gradually

transcribed into codices that were bound as pages and numbered (a dramatic

change in publishing comparable to digital changes today).[2]

'Reference-linking' has not been prominent in discussions about sharing books

online and I only came to realise its significance during my preparations for

this event. There is a tremendous amount of very old, recent and new texts

online but we haven't done much in opening them up to contextual reading. In

this there are publishers of all 'grounds' together.

We are equipped to treat the internet not only as repository and library but

to take into account its potentials of reading that have been hiding in front

of our very eyes. To expand the notion of hyperlink by taking into account

techniques of referencing and to expand the notion of referencing by realising

its plasticity which has always been imagined as if it is there. To mesh texts

with public URLs to enable entaglement of referencing and hyperlinks. Here,

open access gains its further relevance and importance.

Dušan Barok

_Written May 21-23, 2014, in Vienna and Rotterdam. Revised May 28, 2014._

Notes

1. ↑ Proposals for paragraph-based hyperlinking can be traced back to the work of Douglas Engelbart, and today there is a number of related ideas, some of which were implemented on a small scale: fuzzy anchoring, 1(http://hypothes.is/blog/fuzzy-anchoring/); purple numbers, 2(http://project.cim3.net/wiki/PMWX_White_Paper_2008); robust anchors, 3(http://github.com/hypothesis/h/wiki/robust-anchors); _Emphasis_ , 4(http://open.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/01/11/emphasis-update-and-source); and others 5(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragment_identifier#Proposals). The dependence on structural elements such as paragraphs is one of their shortcoming making them not suitable for texts with longer paragraphs (e.g. Adorno's _Aesthetic Theory_ ), visual poetry or computer code; another is the requirement to store anchors along the text.

2. ↑ Works which happened not to be of interest at the time ceased to be copied and mostly disappeared. On the book roll and its gradual replacement by the codex see William A. Johnson, "The Ancient Book", in _The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology_ , ed. Roger S. Bagnall, Oxford, 2009, pp 256-281, 6(http://google.com/books?id=6GRcLuc124oC&pg=PA256).

Addendum (June 9)

Arie Altena wrote a [report from the

panel](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/off-the-press-report-day-

ii/) published on the website of Digital Publishing Toolkit initiative,

followed by another [summary of the

talk](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/dusan-barok-digital-imprint-

the-motion-of-publishing/) by Irina Enache.

The online repository Aaaaarg [has

introduced](http://twitter.com/aaaarg/status/474717492808413184) the

reference-link function in its document viewer, see [an

example](http://aaaaarg.fail/ref/60090008362c07ed5a312cda7d26ecb8#0.102).

Barok

Techniques of Publishing

2014

Techniques of Publishing

Draft translation of a talk given at the seminar Informace mezi komoditou a komunitou [The Information Between Commodity and Community] held at Tranzitdisplay in Prague, Czech Republic, on May 6, 2014

My contribution has three parts. I will begin by sketching the current environment of publishing in general, move on to some of the specificities of publishing

in the humanities and art, and end with a brief introduction to the Monoskop

initiative I was asked to include in my talk.

I would like to thank Milos Vojtechovsky, Matej Strnad and CAS/FAMU for

the invitation, and Tranzitdisplay for hosting this seminar. It offers itself as an

opportunity for reflection for which there is a decent distance from a previous

presentation of Monoskop in Prague eight years ago when I took part in a new

media education workshop prepared by Miloš and Denisa Kera. Many things

changed since then, not only in new media, but in the humanities in general,

and I will try to articulate some of these changes from today’s perspective and

primarily from the perspective of publishing.

I. The Environment of Publishing

One change, perhaps the most serious, and which indeed relates to the humanities

publishing as well, is that from a subject that was just a year ago treated as a paranoia of a bunch of so called technological enthusiasts, is today a fact with which

the global public is well acquainted: we are all being surveilled. Virtually every

utterance on the internet, or rather made by means of the equipment connected

to it through standard protocols, is recorded, in encrypted or unencrypted form,

on servers of information agencies, besides copies of a striking share of these data

on servers of private companies. We are only at the beginning of civil mobilization towards reversal of the situation and the future is open, yet nothing suggests

so far that there is any real alternative other than “to demand the impossible.”

There are at least two certaintes today: surveillance is a feature of every communication technology controlled by third parties, from post, telegraphy, telephony

to internet; and at the same time it is also a feature of the ruling power in all its

variants humankind has come to know. In this regard, democracy can be also understood as the involvement of its participants in deciding on the scale and use of

information collected in this way.

I mention this because it suggests that also all publishing initiatives, from libraries,

through archives, publishing houses to schools have their online activities, back1

ends, shared documents and email communication recorded by public institutions–

which intelligence agencies are, or at least ought to be.

In regard to publishing houses it is notable that books and other publications today are printed from digital files, and are delivered to print over email, thus it is

not surprising to claim that a significant amount of electronically prepared publications is stored on servers in the public service. This means that besides being

required to send a number of printed copies to their national libraries, in fact,

publishers send their electronic versions to information agencies as well. Obviously, agencies couldn’t care less about them, but it doesn’t change anything on

the likely fact that, whatever it means, the world’s largest electronic repository of

publications today are the server farms of the NSA.

Information agencies archive publications without approval, perhaps without awareness, and indeed despite disapproval of their authors and publishers, as an

“incidental” effect of their surveillance techniques. This situation is obviously

radically different from a totalitarianism we got to know. Even though secret

agencies in the Eastern Bloc were blackmailing people to produce miserable literature as their agents, samizdat publications could at least theoretically escape their

attention.

This is not the only difference. While captured samizdats were read by agents of

flesh and blood, publications collected through the internet surveillance are “read”

by software agents. Both of them scan texts for “signals”, ie. terms and phrases

whose occurrences trigger interpretative mechanisms that control operative components of their organizations.

Today, publishing is similarly political and from the point of view of power a potentially subversive activity like it was in the communist Czechoslovakia. The

difference is its scale, reach and technique.

One of the messages of the recent “revelations” is that while it is recommended

to encrypt private communication, the internet is for its users also a medium of

direct contact with power. SEO, or search engine optimization, is now as relevant technique for websites as for books and other publications since all of them

are read by similar algorithms, and authors can read this situation as a political

dimension of their work, as a challenge to transform and model these algorithms

by texts.

2

II. Techniques of research in the humanities literature

Compiling the bibliography

Through the circuitry we got to the audience, readers. Today, they also include

software and algorithms such as those used for “reading” by information agencies

and corporations, and others facilitating reading for the so called ordinary reader,

the reader searching information online, but also the “expert” reader, searching

primarily in library systems.

Libraries, as we said, are different from information agencies in that they are

funded by the public not to hide publications from it but to provide access to

them. A telling paradox of the age is that on the one hand information agencies

are storing almost all contemporary book production in its electronic version,

while generally they absolutely don’t care about them since the “signal” information lies elsewhere, and on the other in order to provide electronic access, paid or

direct, libraries have to costly scan also publications that were prepared for print

electronically.

A more remarkable difference is, of course, that libraries select and catalogize

publications.

Their methods of selection are determined in the first place by their public institutional function of the protector and projector of patriotic values, and it is reflected

in their preference of domestic literature, ie. literature written in official state languages. Methods of catalogization, on the other hand, are characterized by sorting

by bibliographic records, particularly by categories of disciplines ordered in the

tree structure of knowledge. This results in libraries shaping the research, including academic research, towards a discursivity that is national and disciplinary, or

focused on the oeuvre of particular author.

Digitizing catalogue records and allowing readers to search library indexes by their

structural items, ie. the author, publisher, place and year of publication, words in

title, and disciplines, does not at all revert this tendency, but rather extends it to

the web as well.

I do not intend to underestimate the value and benefits of library work, nor the

importance of discipline-centered writing or of the recognition of the oeuvre of

the author. But consider an author working on an article who in the early phase

of his research needs to prepare a bibliography on the activity of Fluxus in central Europe or on the use of documentary film in education. Such research cuts

through national boundaries and/or branches of disciplines and he is left to travel

not only to locate artefacts, protagonists and experts in the field but also to find

literature, which in turn makes even the mere process of compiling bibliography

relatively demanding and costly activity.

3

In this sense, the digitization of publications and archival material, providing their

free online access and enabling fulltext search, in other words “open access”, catalyzes research across political-geographical and disciplinary configurations. Because while the index of the printed book contains only selected terms and for

the purposes of searching the index across several books the researcher has to have

them all at hand, the software-enabled search in digitized texts (with a good OCR)

works with the index of every single term in all of them.

This kind of research also obviously benefits from online translation tools, multilingual case bibliographies online, as well as second hand bookstores and small

specialized libraries that provide a corrective role to public ones, and whose “open

access” potential has been explored to the very small extent until now, but which

I won’t discuss here further for the lack of time.

Writing

The disciplinarity and patriotism are “embedded” in texts themselves, while I repeat that I don’t say this in a pejorative way.

Bibliographic records in bodies of texts, notes, attributions of sources and appended references can be read as formatted addresses of other texts, making apparent a kind of intertextual structure, well known in hypertext documents. However, for the reader these references are still “virtual”. When following a reference

she is led back to a library, and if interested in more references, to more libraries.

Instead, authors assume certain general erudition of their readers, while following references to their very sources is perceived as an exception from the standard

self-limitation to reading only the body of the text. Techniques of writing with

virtual bibliography thus affirm national-disciplinary discourses and form readers

and authors proficient in the field of references set by collections of local libraries

and so called standard literature of fields they became familiar with during their

studies.

When in this regime of writing someone in the Czech Republic wants to refer to

the work of Gilbert Simondon or Alexander Bogdanov, to give an example, the

effect of his work will be minimal, since there was practically nothing from these

authors translated into Czech. His closely reading colleague is left to try ordering

books through a library and wait for 3-4 weeks, or to order them from an online

store, travel to find them or search for them online. This applies, in the case of

these authors, for readers in the vast majority of countries worldwide. And we can

tell with certainty that this is not only the case of Simondon and Bogdanov but

of the vast majority of authors. Libraries as nationally and pyramidally situated

institutions face real challenges in regard to the needs of free research.

This is surely merely one aspect of techniques of writing.

4

Reading

Reading texts with “live” references and bibliographies using electronic devices is

today possible not only to imagine but to realise as well. This way of reading

allows following references to other texts, visual material, other related texts of

an author, but also working with occurrences of words in the text, etc., bringing

reading closer to textual analysis and other interesting levels. Due to the time

limits I am going to sketch only one example.

Linear reading is specific by reading from the beginning of the text to its end,

as well as ‘tree-like’ reading through the content structure of the document, and

through occurrences of indexed words. Still, techniques of close reading extend

its other aspect – ‘moving’ through bibliographic references in the document to

particular pages or passages in another. They make the virtual reference plastic –

texts are separated one from another merely by a click or a tap.

We are well familiar with a similar movement through the content on the web

– surfing, browsing, and clicking through. This leads us to an interesting parallel: standards of structuring, composing, etc., of texts in the humanities has been

evolving for centuries, what is incomparably more to decades of the web. From

this stems also one of the historical challenges the humanities are facing today:

how to attune to the existence of the web and most importantly to epistemological consequences of its irreversible social penetration. To upload a PDF online is

only a taste of changes in how we gain and make knowledge and how we know.

This applies both ways – what is at stake is not only making production of the

humanities “available” online, it is not only about open access, but also about the

ways of how the humanities realise the electronic and technical reality of their

own production, in regard to the research, writing, reading, and publishing.

Publishing

The analogy between information agencies and national libraries also points to

the fact that large portion of publications, particularly those created in software,

is electronic. However the exceptions are significant. They include works made,

typeset, illustrated and copied manually, such as manuscripts written on paper

or other media, by hand or using a typewriter or other mechanic means, and

other pre-digital techniques such as lithography, offset, etc., or various forms of

writing such as clay tablets, rolls, codices, in other words the history of print and

publishing in its striking variety, all of which provide authors and publishers with

heterogenous means of expression. Although this “segment” is today generally

perceived as artists’ books interesting primarily for collectors, the current process

of massive digitization has triggered the revival, comebacks, transformations and

5

novel approaches to publishing. And it is these publications whose nature is closer

to the label ‘book’ rather than the automated electro-chemical version of the offset

lithography of digital files on acid-free paper.

Despite that it is remarkable to observe a view spreading among publishers that

books created in software are books with attributes we have known for ages. On

top of that there is a tendency to handle files such as PDFs, EPUBs, MOBIs and

others as if they are printed books, even subject to the rules of limited edition, a

consequence of what can be found in the rise of so called electronic libraries that

“borrow” PDF files and while someone reads one, other users are left to wait in

the line.

Whilst, from today’s point of view of the humanities research, mass-printed books

are in the first place archives of the cultural content preserved in this way for the

time we run out of electricity or have the internet ‘switched off’ in some other

way.

III. Monoskop

Finally, I am getting to Monoskop and to begin with I am going to try to formulate

its brief definition, in three versions.

From the point of view of the humanities, Monoskop is a research, or questioning, whose object’s nature renders no answer as definite, since the object includes

art and culture in their widest sense, from folk music, through visual poetry to

experimental film, and namely their history as well as theory and techniques. The

research is framed by the means of recording itself, what makes it a practise whose

record is an expression with aesthetic qualities, what in turn means that the process of the research is subject to creative decisions whose outcomes are perceived

esthetically as well.

In the language of cultural management Monoskop is an independent research

project whose aim is subject to change according to its continual findings; which

has no legal body and thus as organisation it does not apply for funding; its participants have no set roles; and notably, it operates with no deadlines. It has a reach

to the global public about which, respecting the privacy of internet users, there

are no statistics other than general statistics on its social networks channels and a

figure of numbers of people and bots who registered on its website and subscribed

to its newsletter.

At the same time, technically said, Monoskop is primarily an internet website

and in this regard it is no different from any other communication media whose

function is to complicate interpersonal communication, at least due to the fact

that it is a medium with its own specific language, materiality, duration and access.

6

Contemporary media

Monoskop has began ten years ago in the milieu of a group of people running

a cultural space where they had organised events, workshops, discussion, a festival,

etc. Their expertise, if to call that way the trace left after years spent in the higher

education, varied well, and it spanned from fine art, architecture, philosophy,

through art history and literary theory, to library studies, cognitive science and

information technology. Each of us was obviously interested in these and other

fields other than his and her own, but the praxis in naming the substance whose

centripetal effects brought us into collaboration were the terms new media, media

culture and media art.

Notably, it was not contemporary art, because a constituent part of the praxis was

also non-visual expression, information media, etc., so the research began with the

essentially naive question ‘of what are we contemporary?’. There had been not

much written about media culture and art as such, a fact I perceived as drawback

but also as challenge.

The reflection, discussion and critique need to be grounded in reality, in a wider

context of the field, thus the research has began in-field. From the beginning, the

website of Monoskop served to record the environment, including people, groups,

organizations, events we had been in touch with and who/which were more or

less explicitly affiliated with media culture. The result of this is primarily a social

geography of live media culture and art, structured on the wiki into cities, with

a focus on the two recent decades.

Cities and agents

The first aim was to compile an overview of agents of this geography in their

wide variety, from eg. small independent and short-lived initiatives to established

museums. The focus on the 1990s and 2000s is of course problematic. One of

its qualities is a parallel to the history of the World Wide Web which goes back

precisely to the early 1990s and which is on the one hand the primary recording

medium of the Monoskop research and on the other a relevant self-archiving and–

stemming from its properties–presentation medium, in other words a platform on

which agents are not only meeting together but potentially influence one another

as well.

http://monoskop.org/Prague

The records are of diverse length and quality, while the priorities for what they

consist of can be generally summed up in several points in the following order:

7

1. Inclusion of a person, organisation or event in the context of the structure.

So in case of a festival or conference held in Prague the most important is to

mention it in the events section on the page on Prague.

2. Links to their web presence from inside their wiki pages, while it usually

implies their (self-)presentation.

http://monoskop.org/The_Media_Are_With_Us

3. Basic information, including a name or title in an original language, dates

of birth, foundation, realization, relations to other agents, ideally through

links inside the wiki. These are presented in narrative and in English.

4. Literature or bibliography in as many languages as possible, with links to

versions of texts online if there are any.

5. Biographical and other information relevant for the object of the research,

while the preference is for those appearing online for the first time.

6. Audiovisual material, works, especially those that cannot be found on linked

websites.

Even though pages are structured in the quasi same way, input fields are not structured, so when you create a wiki account and decide to edit or add an entry, the

wiki editor offers you merely one input box for the continuous text. As is the case

on other wiki websites. Better way to describe their format is thus articles.

There are many related questions about representation, research methodology,

openness and participation, formalization, etc., but I am not going to discuss them

due to the time constraint.

The first research layer thus consists of live and active agents, relations among

them and with them.

Countries

Another layer is related to a question about what does the field of media culture

and art stem from; what and upon what does it consciously, but also not fully

consciously, builds, comments, relates, negates; in other words of what it may be

perceived a post, meta, anti, retro, quasi and neo legacy.

An approach of national histories of art of the 20th century proved itself to be

relevant here. These entries are structured in the same way like cities: people,

groups, events, literature, at the same time building upon historical art forms and

periods as they are reflected in a range of literature.

8

http://monoskop.org/Czech_Republic

The overviews are organised purposely without any attempts for making relations

to the present more explicit, in order to leave open a wide range of intepretations

and connotations and to encourage them at the same time.

The focus on art of the 20th century originally related to, while the researched

countries were mostly of central and eastern Europe, with foundations of modern

national states, formations preserving this field in archives, museums, collections

but also publications, etc. Obviously I am not saying that contemporary media

culture is necessarily archived on the web while art of the 20th century lies in

collections “offline”, it applies vice versa as well.

In this way there began to appear new articles about filmmakers, fine artists, theorists and other partakers in artistic life of the previous century.

Since then the focus has considerably expanded to more than a century of art and

new media on the whole continent. Still it portrays merely another layer of the

research, the one which is yet a collection of fragmentary data, without much

context. Soon we also hit the limit of what is about this field online. The next

question was how to work in the internet environment with printed sources.

Log

http://monoskop.org/log

When I was installing this blog five years ago I treated it as a side project, an offshoot, which by the fact of being online may not be only an archive of selected

source literature for the Monoskop research but also a resource for others, mainly

students in the humanities. A few months later I found Aaaarg, then oriented

mainly on critical theory and philosophy; there was also Gigapedia with publications without thematic orientation; and several other community library portals

on password. These were the first sources where I was finding relevant literature

in electronic version, later on there were others too, I began to scan books and catalogues myself and to receive a large number of scans by email and soon came to

realise that every new entry is an event of its own not only for myself. According

to the response, the website has a wide usership across all the continents.

At this point it is proper to mention the copyright. When deciding about whether

to include this or that publication, there are at least two moments always present.

One brings me back to my local library at the outskirts of Bratislava in the early

1990s and asks that if I would have found this book there and then, could it change

my life? Because books that did I was given only later and elsewhere; and here I

think of people sitting behind computers in Belarus, China or Kongo. And even

9

if not, the latter is a wonder on whether this text has a potential to open up some

serious questions about disciplinarity or national discursivity in the humanities,

while here I am reminded by a recent study which claims that more than half

of academic publications are not read by more than three people: their author,

reviewer and editor. What does not imply that it is necessary to promote them

to more people but rather to think of reasons why is it so. It seems that the

consequences of the combination of high selectivity with open access resonate

also with publishers and authors from whom the complaints are rather scarce and

even if sometimes I don’t understand reasons of those received, I respect them.

Media technology

Throughout the years I came to learn, from the ontological perspective, two main

findings about media and technology.

For a long time I had a tendency to treat technologies as objects, things, while now

it seems much more productive to see them as processes, techniques. As indeed

nor the biologist does speak about the dear as biology. In this sense technology is

the science of techniques, including cultural techniques which span from reading,

writing and counting to painting, programming and publishing.

Media in the humanities are a compound of two long unrelated histories. One of

them treats media as a means of communication, signals sent from point A to the

point B, lacking the context and meaning. Another speaks about media as artistic

means of expression, such as the painting, sculpture, poetry, theatre, music or

film. The term “media art” is emblematic for this amalgam while the historical

awareness of these two threads sheds new light on it.

Media technology in art and the humanities continues to be the primary object of

research of Monoskop.

I attempted to comment on political, esthetic and technical aspects of publishing.

Let me finish by saying that Monoskop is an initiative open to people and future

and you are more than welcome to take part in it.

Dušan Barok

Written May 1-7, 2014, in Bergen and Prague. Translated by the author on May 10-13,

2014. This version generated June 10, 2014.