_A talk given on the second day of the conference_ [Off the

Press](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/22-23-may-2014/program/) _held at

WORM, Rotterdam, on May 23, 2014. Also available

in[PDF](/images/2/28/Barok_2014_Communing_Texts.pdf "Barok 2014 Communing

Texts.pdf")._

I am going to talk about publishing in the humanities, including scanning

culture, and its unrealised potentials online. For this I will treat the

internet not only as a platform for storage and distribution but also as a

medium with its own specific means for reading and writing, and consider the

relevance of plain text and its various rendering formats, such as HTML, XML,

markdown, wikitext and TeX.

One of the main reasons why books today are downloaded and bookmarked but

hardly read is the fact that they may contain something relevant but they

begin at the beginning and end at the end; or at least we are used to treat

them in this way. E-book readers and browsers are equipped with fulltext

search functionality but the search for "how does the internet change the way

we read" doesn't yield anything interesting but the diversion of attention.

Whilst there are dozens of books written on this issue. When being insistent,

one easily ends up with a folder with dozens of other books, stucked with how

to read them. There is a plethora of books online, yet there are indeed mostly

machines reading them.

It is surely tempting to celebrate or to despise the age of artificial

intelligence, flat ontology and narrowing down the differences between humans

and machines, and to write books as if only for machines or return to the

analogue, but we may as well look back and reconsider the beauty of simple

linear reading of the age of print, not for nostalgia but for what we can

learn from it.

This perspective implies treating texts in their context, and particularly in

the way they commute, how they are brought in relations with one another, into

a community, by the mere act of writing, through a technique that have

developed over time into what we have came to call _referencing_. While in the

early days referring to texts was practised simply as verbal description of a

referred writing, over millenia it evolved into a technique with standardised

practices and styles, and accordingly: it gained _precision_. This precision

is however nothing machinic, since referring to particular passages in other

texts instead of texts as wholes is an act of comradeship because it spares

the reader time when locating the passage. It also makes apparent that it is

through contexts that the web of printed books has been woven. But even though

referencing in its precision has been meant to be very concrete, particularly

the advent of the web made apparent that it is instead _virtual_. And for the

reader, laborous to follow. The web has shown and taught us that a reference

from one document to another can be plastic. To follow a reference from a

printed book the reader has to stand up, walk down the street to a library,

pick up the referred volume, flip through its pages until the referred one is

found and then follow the text until the passage most probably implied in the

text is identified, while on the web the reader, _ideally_ , merely moves her

finger a few milimeters. To click or tap; the difference between the long way

and the short way is obviously the hyperlink. Of course, in the absence of the

short way, even scholars are used to follow the reference the long way only as

an exception: there was established an unwritten rule to write for readers who

are familiar with literature in the respective field (what in turn reproduces

disciplinarity of the reader and writer), while in the case of unfamiliarity

with referred passage the reader inducts its content by interpreting its

interpretation of the writer. The beauty of reading across references was

never fully realised. But now our question is, can we be so certain that this

practice is still necessary today?

The web silently brought about a way to _implement_ the plasticity of this

pointing although it has not been realised as the legacy of referencing as we

know it from print. Today, when linking a text and having a particular passage

in mind, and even describing it in detail, the majority of links physically

point merely to the beginning of the text. Hyperlinks are linking documents as

wholes by default and the use of anchors in texts has been hardly thought of

as a _requirement_ to enable precise linking.

If we look at popular online journalism and its use of hyperlinks within the

text body we may claim that rarely someone can afford to read all those linked

articles, not even talking about hundreds of pages long reports and the like

and if something is wrong, it would get corrected via comments anyway. On the

internet, the writer is meant to be in more immediate feedback with the

reader. But not always readers are keen to comment and not always they are

allowed to. We may be easily driven to forget that quoting half of the

sentence is never quoting a full sentence, and if there ought to be the entire

quote, its source text in its whole length would need to be quoted. Think of

the quote _information wants to be free_ , which is rarely quoted with its

wider context taken into account. Even factoids, numbers, can be carbon-quoted

but if taken out of the context their meaning can be shaped significantly. The

reason for aversion to follow a reference may well be that we are usually

pointed to begin reading another text from its beginning.

While this is exactly where the practices of linking as on the web and

referencing as in scholarly work may benefit from one another. The question is

_how_ to bring them closer together.

An approach I am going to propose requires a conceptual leap to something we

have not been taught.

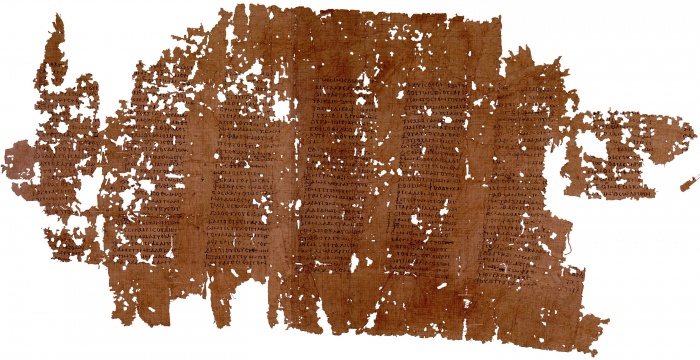

For centuries, the primary format of the text has been the page, a vessel, a

medium, a frame containing text embedded between straight, less or more

explicit, horizontal and vertical borders. Even before the material of the

page such as papyrus and paper appeared, the text was already contained in

lines and columns, a structure which we have learnt to perceive as a grid. The

idea of the grid allows us to view text as being structured in lines and

pages, that are in turn in hand if something is to be referred to. Pages are

counted as the distance from the beginning of the book, and lines as the

distance from the beginning of the page. It is not surprising because it is in

accord with inherent quality of its material medium -- a sheet of paper has a

shape which in turn shapes a body of a text. This tradition goes as far as to

the Ancient times and the bookroll in which we indeed find textual grids.

[](/File:Papyrus_of_Plato_Phaedrus.jpg)

A crucial difference between print and digital is that text files such as HTML

documents nor markdown documents nor database-driven texts did inherit this

quality. Their containers are simply not structured into pages, precisely

because of the nature of their materiality as media. Files are written on

memory drives in scattered chunks, beginning at point A and ending at point B

of a drive, continuing from C until D, and so on. Where does each of these

chunks start is ultimately independent from what it contains.

Forensic archaeologists would confirm that when a portion of a text survives,

in the case of ASCII documents it is not a page here and page there, or the

first half of the book, but textual blocks from completely arbitrary places of

the document.

This may sound unrelated to how we, humans, structure our writing in HTML

documents, emails, Office documents, even computer code, but it is a reminder

that we structure them for habitual (interfaces are rectangular) and cultural

(human-readability) reasons rather then for a technical necessity that would

stem from material properties of the medium. This distinction is apparent for

example in HTML, XML, wikitext and TeX documents with their content being both

stored on the physical drive and treated when rendered for reading interfaces

as single flow of text, and the same goes for other texts when treated with

automatic line-break setting turned off. Because line-breaks and spaces and

everything else is merely a number corresponding to a symbol in character set.

So how to address a section in this kind of document? An option offers itself

-- how computers do, or rather how we made them do it -- as a position of the

beginning of the section in the array, in one long line. It would mean to

treat the text document not in its grid-like format but as line, which merely

adapts to properties of its display when rendered. As it is nicely implied in

the animated logo of this event and as we know it from EPUBs for example.

In the case of 'reference-linking' we can refer to a passage by including the

information about its beginning and length determined by the character

position within the text (in analogy to _pp._ operator used for printed

publications) as well as the text version information (in printed texts served

by edition and date of publication). So what is common in printed text as the

page information is here replaced by the character position range and version.

Such a reference-link is more precise while addressing particular section of a

particular version of a document regardless of how it is rendered on an

interface.

It is a relatively simple idea and its implementation does not be seem to be

very hard, although I wonder why it has not been implemented already. I

discussed it with several people yesterday to find out there were indeed

already attempts in this direction. Adam Hyde pointed me to a proposal for

_fuzzy anchors_ presented on the blog of the Hypothes.is initiative last year,

which in order to overcome the need for versioning employs diff algorithms to

locate the referred section, although it is too complicated to be explained in

this setting.[1] Aaaarg has recently implemented in its PDF reader an option

to generate URLs for a particular point in the scanned document which itself

is a great improvement although it treats texts as images, thus being specific

to a particular scan of a book, and generated links are not public URLs.

Using the character position in references requires an agreement on how to

count. There are at least two options. One is to include all source code in

positioning, which means measuring the distance from the anchor such as the

beginning of the text, the beginning of the chapter, or the beginning of the

paragraph. The second option is to make a distinction between operators and

operands, and count only in operands. Here there are further options where to

make the line between them. We can consider as operands only characters with

phonetic properties -- letters, numbers and symbols, stripping the text from

operators that are there to shape sonic and visual rendering of the text such

as whitespaces, commas, periods, HTML and markdown and other tags so that we

are left with the body of the text to count in. This would mean to render

operators unreferrable and count as in _scriptio continua_.

_Scriptio continua_ is a very old example of the linear onedimensional

treatment of the text. Let's look again at the bookroll with Plato's writing.

Even though it is 'designed' into grids on a closer look it reveals the lack

of any other structural elements -- there are no spaces, commas, periods or

line-breaks, the text is merely one flow, one long line.

_Phaedrus_ was written in the fourth century BC (this copy comes from the

second century AD). Word and paragraph separators were reintroduced much

later, between the second and sixth century AD when rolls were gradually

transcribed into codices that were bound as pages and numbered (a dramatic

change in publishing comparable to digital changes today).[2]

'Reference-linking' has not been prominent in discussions about sharing books

online and I only came to realise its significance during my preparations for

this event. There is a tremendous amount of very old, recent and new texts

online but we haven't done much in opening them up to contextual reading. In

this there are publishers of all 'grounds' together.

We are equipped to treat the internet not only as repository and library but

to take into account its potentials of reading that have been hiding in front

of our very eyes. To expand the notion of hyperlink by taking into account

techniques of referencing and to expand the notion of referencing by realising

its plasticity which has always been imagined as if it is there. To mesh texts

with public URLs to enable entaglement of referencing and hyperlinks. Here,

open access gains its further relevance and importance.

Dušan Barok

_Written May 21-23, 2014, in Vienna and Rotterdam. Revised May 28, 2014._

Notes

1. ↑ Proposals for paragraph-based hyperlinking can be traced back to the work of Douglas Engelbart, and today there is a number of related ideas, some of which were implemented on a small scale: fuzzy anchoring, 1(http://hypothes.is/blog/fuzzy-anchoring/); purple numbers, 2(http://project.cim3.net/wiki/PMWX_White_Paper_2008); robust anchors, 3(http://github.com/hypothesis/h/wiki/robust-anchors); _Emphasis_ , 4(http://open.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/01/11/emphasis-update-and-source); and others 5(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragment_identifier#Proposals). The dependence on structural elements such as paragraphs is one of their shortcoming making them not suitable for texts with longer paragraphs (e.g. Adorno's _Aesthetic Theory_ ), visual poetry or computer code; another is the requirement to store anchors along the text.

2. ↑ Works which happened not to be of interest at the time ceased to be copied and mostly disappeared. On the book roll and its gradual replacement by the codex see William A. Johnson, "The Ancient Book", in _The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology_ , ed. Roger S. Bagnall, Oxford, 2009, pp 256-281, 6(http://google.com/books?id=6GRcLuc124oC&pg=PA256).

Addendum (June 9)

Arie Altena wrote a [report from the

panel](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/off-the-press-report-day-

ii/) published on the website of Digital Publishing Toolkit initiative,

followed by another [summary of the

talk](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/dusan-barok-digital-imprint-

the-motion-of-publishing/) by Irina Enache.

The online repository Aaaaarg [has

introduced](http://twitter.com/aaaarg/status/474717492808413184) the

reference-link function in its document viewer, see [an

example](http://aaaaarg.fail/ref/60090008362c07ed5a312cda7d26ecb8#0.102).

Mars, Medak & Sekulic

Taken Literally

2016

Taken literally

Marcell Mars

Tomislav Medak

Dubravka Sekulic

Free people united in building a society of

equals, embracing those whom previous

efforts have failed to recognize, are the historical foundation of the struggle against

enslavement, exploitation, discrimination

and cynicism. Building a society has never

been an easy-going pastime.

During the turbulent 20th century,

different trajectories of social transformation moved within the horizon set by

the revolutions of the 18th and 19th century: equality, brotherhood and liberty

– and class struggle. The 20th century experimented with various combinations

of economic and social rationales in the

arrangement of social reproduction. The

processes of struggle, negotiation, empowerment and inclusion of discriminated social groups constantly complexified and

dynamised the basic concepts regulating

social relations. However, after the process

of intensive socialisation in the form of either welfare state or socialism that dominated a good part of the 20th century, the

end of the century was marked by a return

in the regulation of social relations back

to the model of market domination and

private appropriation. Such simplification

and fall from complexity into a formulaic

state of affairs is not merely a symptom

of overall exhaustion, loss of imagination

and lacking perspective on further social

development, but rather indicates a cynical

abandonment of the effort to build society,

its idea, its vision – and, as some would

want, of society altogether.

In this article, we wish to revisit the

evolution of regulation of ownership in the

field of intellectual production and housing

as two examples of the historical dead-end

in which we find ourselves.

T H E C A P I TA L I S T M O D E

O F P RO D U C T I O N

According to the text-book definition, the

capitalist mode of production is the first

historical organisation of socio-economic relations in which appropriation of the

surplus from producers does not depend

on force, but rather on neutral laws of economic processes on the basis of which the

capitalist and the worker enter voluntarily

into a relation of production. While under

feudalism it was the aristocratic oligopoly

on violence that secured a hereditary hierarchy of appropriation, under capitalism the

neutral logic of appropriation was secured

by the state monopoly on violence. However, given that the early capitalist relations

in the English country-side did not emerge

outside the existing feudal inequalities, and

that the process of generalisation of capitalist relations, particularly after the rise of industrialisation, resulted in even greater and

even more hardened stratification, the state

monopoly on violence securing the neutral

logic of appropriation ended up mostly securing the hereditary hierarchy of appropriation. Although in the new social formation

neither the capitalist nor the worker was born

capitalist or born worker, the capitalist would

rarely become a worker and the worker a capitalist even rarer. However, under conditions

where the state monopoly on violence could

no longer coerce workers to voluntarily sell

their labour and where their resistance to

accept existing class relations could be

229

expressed in the withdrawal of their labour

power from the production process, their

consent would become a problem for the existing social model. That problem found its

resolution through a series of conflicts that

have resulted in historical concessions and

gains of class struggle ranging from guaranteed labor rights, through institutions of the

welfare state, to socialism.

The fundamental property relation

in the capitalist mode of production is that

the worker has an exclusive ownership over

his/her own labour power, while the capitalist has ownership over the means of production. By purchasing the worker's labour

power, the capitalist obtains the exclusive

right to appropriate the entire product of

worker's labour. However, as the regulation

of property in such unconditional formulaic

form quickly results in deep inequalities, it

could not be maintained beyond the early

days of capitalism. Resulting class struggles

and compromises would achieve a series of

conditions that would successively complexify the property relations.

Therefore, the issue of private property – which goods do we have the right to

call our own to the exclusion of others: our

clothes, the flat in which we live, means of

production, profit from the production process, the beach upon which we wish to enjoy

ourselves alone or to utilise by renting it out,

unused land in our neighbourhood – is not

merely a question of the optimal economic

allocation of goods, but also a question of

social rights and emancipatory opportunities that are required in order secure the

continuous consent of society's members to

its organisational arrangements.

230

Taken literally

OW NER S H I P R EG I M ES

Both the concept of private property over

land and the concept of copyright and

intellectual property have their shared

evolutionary beginnings during the early capitalism in England, at a time when

the newly emerging capitalist class was

building up its position in relation to the

aristocracy and the Church. In both cases, new actors entered into the processes

of political articulation, decision-making

and redistribution of power. However, the

basic process of ( re )defining relations has

remained ( until today ) a spatial demarcation: the question of who is excluded or

remains outside and how.

① In the early period of trade in books, after

the invention of the printing press in the 15th

century, the exclusive rights to commercial

exploitation of written works were obtained

through special permits from the Royal Censors, issued solely to politically loyal printers.

The copyright itself was constituted only in

the 17th century. It's economic function is to

unambiguously establish the ownership title

over the products of intellectual labour. Once

that title is established, there is a person with

whose consent the publisher can proceed in

commodifying and distributing the work to

the exclusion of others from its exploitation.

And while that right to economic benefit was

exclusively that of the publishers at the outset, as authors became increasingl aware that

the income from books guaranteed then an

autonomy from the sponsorship of the King

and the aristocracy, in the 19th century copyright gradually transformed into a legal right

that protected both the author and the publisher in equal measure. The patent rights underwent a similar development. They were

standardised in the 17th century as a precondition for industrial development, and were

soon established as a balance between the

rights of the individual-inventor and the

commercial interest of the manufacturer.

However, the balance of interests between the productive creative individuals

and corporations handling production and

distribution did not last long and, with

time, that balance started to lean further

towards protecting the interests of the corporations. With the growing complexity of

companies and their growing dependence

on intellectual property rights as instruments in 20th century competitive struggles, the economic aspect of intellectual

property increasingly passed to the corporation, while the author/inventor was

left only with the moral and reputational

element. The growing importance of intellectual property rights for the capitalist

economy has been evident over the last

three decades in the regular expansions of

the subject matter and duration of protection, but, most important of all – within

the larger process of integration of the capitalist world-system – in the global harmonisation and enforcement of rights protection. Despite the fact that the interests of

authors and the interests of corporations,

of the global south and the global north, of

the public interest and the corporate interest do not fall together, we are being given

a global and uniform – formulaic – rule of

the abstract logic of ownership, notwithstanding the diverging circumstances and

interests of different societies in the context of uneven development.

No-one is surprised today that, in

spite of their initial promises, the technological advances brought by the Internet,

once saddled with the existing copyright

regulation, did not enhance and expand

access to knowledge. But that dysfunction

is nowhere more evident than in academic publishing. This is a global industry of

the size of music recording industry dominated by an oligopoly of five major commercial publishers: Reed Elsevier, Taylor

& Francis, Springer, Wiley-Blackwell and

Sage. While scientists write their papers,

do peer-reviews and edit journals for free,

these publishers have over past decades

taken advantage of their oligopolistic position to raise the rates of subscriptions they

sell mostly to publicly financed libraries at

academic institutions, so that the majority of libraries, even in the rich centres of

the global north, are unable to afford access to many journals. The fantastic profit

margins of over 30% that these publishers

reap from year to year are premised on denying access to scientific publications and

the latest developments in science not only

to the general public, but also students and

scholars around the world. Although that

oligopoly rests largely on the rights of the

authors, the authors receive no benefit

from that copyright. An even greater irony is, if they want to make their work open

access to others, the authors themselves or

the institutions that have financed the underlying research through the proxy of the

author are obliged to pay additionally to

the publishers for that ‘service’. ×

231

② With proliferation of enclosures and

signposts prohibiting access, picturesque

rural arcadias became landscapes of capitalistic exploitation. Those evicted by the

process of enclosure moved to the cities

and became wage workers. Far away from

the parts of the cities around the factories,

where working families lived squeezed

into one room with no natural light and

ventilation, areas of the city sprang up in

which the capitalists built their mansions.

At that time, the very possibility of participation in political life was conditioned

on private property, thus excluding and

discriminating by legal means entire social

groups. Women had neither the right to

property ownership nor inheritance rights.

Engels' description of the humiliating

living conditions of Manchester workers in

the 19th century pointed to the catastrophic

effects of industrialisation on the situation

of working class ( e.g. lower pay than during

the pre-industrial era ) and indicated that

the housing problem was not a direct consequence of exploitation but rather a problem

arising from inequitable redistribution of

assets. The idea that living quarters for the

workers could be pleasant, healthy and safe

places in which privacy was possible and

that that was not the exclusive right of the

rich, became an integral part of the struggle

for labor rights, and part of the consciousness of progressive, socially-minded architects and all others dedicated to solving the

housing problem.

Just as joining forces was as the

foundation of their struggle for labor and

political rights, joining forces was and has

remained the mechanism for addressing the

232

Taken literally

inadequate housing conditions. As early as

during the 19th century, Dutch working class

and impoverished bourgeoisie joined forces

in forming housing co-operatives and housing societies, squatting and building without permits on the edges of the cities. The

workers' struggle, enlightened bourgeoisie,

continued industrial development, as well

as the phenomenon of Utopian socialist-capitalists like Jean-Baptiste André Godin, who, for example, under the influence

of Charles Fourier's ideas, built a palace for

workers – the Familistery, all these exerted

pressure on the system and contributed to

the improvement of housing conditions for

workers. Still, the dominant model continued to replicate the rentier system in which

even those with inadequate housing found

someone to whom they could rent out a segment of their housing unit.

The general social collapse after

World War I, the Socialist Revolution and

the coming to power in certain European

cities of the social-democrats brought new

urban strategies. In ‘red’ Vienna, initially

under the urban planning leadership of

Otto Neurath, socially just housing policy

and provision of adequate housing was regarded as the city's responsibility. The city

considered the workers who were impoverished by the war and who sought a way out

of their homelessness by building housing

themselves and tilling gardens as a phenomenon that should be integrated, and

not as an error that needed to be rectified.

Sweden throughout the 1930s continued

with its right to housing policy and served

as an example right up until the mid-1970s

both to the socialist and ( capitalist ) wel-

fare states. The idea of ( private ) ownership became complexified with the idea

of social ownership ( in Yugoslavia ) and

public/social housing elsewhere, but since

the bureaucratic-technological system responsible for implementation was almost

exclusively linked with the State, housing

ended up in unwieldy complicated systems

in which there was under-investment in

maintenance. That crisis was exploited as

an excuse to impose as necessary paradigmatic changes that we today regard as the

beginning of neo-liberal policies.

At the beginning of the 1980s in

Great Britain, Margaret Thatcher created an atmosphere of a state of emergency

around the issue of housing ownership

and, with the passing of the Housing Act

in 1980, reform was set in motion that

would deeply transform the lives of the

Brits. The promises of a better life merely

based on the opportunity to buy and become a ( private ) owner never materialised.

The transition from the ‘right to housing’ and the ‘right to ( participation in the

market through ) purchase’ left housing

to the market. There the prices first fell

drastically at the beginning of the 1990s.

That was followed by a financialisation

and speculation on the property market

making housing space in cities like London primarily an avenue of investment, a

currency, a tax haven and a mechanism

by which the rich could store their wealth.

In today's generation, working and lower

classes, even sometimes the upper middle

class can no longer even dream of buying

a flat in London. ×

P L AT F O R M I SAT I O N

Social ownership and housing – understood both literally as living space, but

also as the articulation of the right to decent life for all members of society – which

was already under attack for decades prior,

would be caught completely unprepared

for the information revolution and its

zero marginal cost economy. Take for

example the internet innovation: after a

brief period of comradely couch-surfing,

the company AirBnB in an even shorter period transformed from the service

allowing small enterprising home owners to rent out their vacant rooms into a

catalyst for amassing the ownership over

housing stock with the sole purpose of

renting it out through AirBnb. In the

last phase of that transformation, new

start-ups appeared that offered to the

newly consolidated feudal lords the service of easier management of their housing ‘fleet’, where the innovative approach

boils down to the summoning of service

workers who, just like Uber drivers, seek

out blue dots on their smart-phone maps

desperately rushing – in fear of bad rating,

for a minimal fee and no taxes paid – to

turn up there before their equally precarious competition does. With these innovations, the residents end up being offered

shorter and shorter but increasingly more

expensive contracts on rental, while in a

worse case the flats are left unoccupied

because the rich owner-investors have

realised that an unoccupied flat is a more

profitable deal than a risky investment in

a market in crisis.

233

The information revolution stepped out

onto the historical stage with the promise

of radical democratisation of communication, culture and politics. Anyone could

become the media and address the global

public, emancipate from the constrictive

space of identity, and obtain access to entire

knowledge of the world. However, instead

of resulting in democratising and emancipatory processes, with the handing over of

Internet and technological innovation to the

market in 1990s it resulted in the gradual

disruption of previous social arrangements

in the allocation of goods and in the intensification of the commodification process.

That trajectory reached its full-blown development in the form of Internet platforms

that simultaneously enabled old owners of

goods to control more closely their accessibility and permited new owners to seek out

new forms of commercial exploitation. Take

for example Google Books, where the process of digitization of the entire printed culture of the world resulted in no more than

ad and retail space where only few books

can be accessed for free. Or Amazon Kinde,

where the owner of the platform has such

dramatic control over books that on behest

of copyright holders it can remotely delete

a purchased copy of a book, as quite indicatively happened in 2009 with Orwell's 1984.

The promised technological innovation that

would bring a new turn of the complexity in

the social allocation of goods resulted in a

simplification and reduction of everything

into private property.

The history of resistance to such extreme forms of enclosure of culture and

knowledge is only a bit younger than the

234

Taken literally

processes of commodification themselves

that had begun with the rise of trade in

books. As early as the French Revolution,

the confiscation of books from the libraries

of clergy and aristocracy and their transfer

into national and provincial libraries signalled that the right of access to knowledge

was a pre-condition for full participation

in society. For its part, the British labor

movement of the mid-19th century had to

resort to opening workers' reading-rooms,

projects of proletarian self-education and

the class struggle in order to achieve the

establishment of the institution of public

libraries financed by taxes, and the right

thereby for access to knowledge and culture for all members of society.

SHAD OW P U B L I C L I B R A R I ES

Public library as a space of exemption from

commodification of knowledge and culture

is an institution that complexifies the unconditional and formulaic application of

intellectual property rights, making them

conditional on the public interest that all

members of the society have the right of

access to knowledge. However, with the

transition to the digital, public libraries

have been radically limited in acquiring

anything they could later provide a decommodified access to. Publishers do not

wish to sell electronic books to libraries,

and when they do decide to give them a

lending licence, that licence runs out after 26 lendings. Closed platforms for electronic publications where the publishers

technologically control both the medium

and the ways the work can be used take us

back to the original and not very well-conceived metaphor of ownership – anyone

who owns the land can literally control

everything that happens on that land –

even if that land is the collective process

of writing and reading. Such limited space

for the activity of public libraries is in radical contrast to the potentials for universal

access to all of culture and knowledge that

digital distribution could make possible

at a very low cost, but with considerable

change in the regulation of intellectual production in society.

Since such change would not be in the

interest of formulaic application of intellectual property, acts of civil disobedience to

that regime have over the last twenty years

created a number of 'shadow public libraries'

that provide universal access to knowledge

and culture in the digital domain in the way

that the public libraries are not allowed to:

Library Genesis, Science Hub, Aaaaarg,

Monoskop, Memory of the World or Ubuweb. They all have a simple objective – to

provide access to books, journals and digitised knowledge to all who find themselves

outside the rich academic institutions of the

West and who do not have the privilege of

institutional access.

These shadow public libraries bravely remind society of all the watershed moments in the struggles and negotiations

that have resulted in the establishment

of social institutions, so as to first enable

the transition from what was an unjust,

discriminating and exploitative to a better society, and later guarantee that these

gains would not be dismantled or rescinded. That reminder is, however, more than a

mere hacker pastime, just as the reactions

of the corporations are not easy-going at

all: in mid-2015, Reed Elsevier initiated

a court case against Library Genesis and

Science Hub and by the end of 2015 the

court in New York issued a preliminary

injunction ordering the shut-down of

their domains and access to the servers. At

the same time, a court case was brought

against Aaaaarg in Quebec.

Shadow public libraries are also a

reminder of how technological complexity does not have to be harnessed only in

the conversion of socialised resources back

into the simplified formulaic logic of private property, how we can take technology

in our hands, in the hands of society that is

not dismantling its own foundations, but

rather taking care of and preserving what

is worthwhile and already built – and thus

building itself further. But, most powerfully shadow public libraries are a reminder to us of how the focus and objective of

our efforts should not be a world that can

be readily managed algorithmically, but a

world in which our much greater achievement is the right guaranteed by institutions – envisioned, demanded, struggled

for and negotiated – a society. Platformisation, corporate concentration, financialisation and speculation, although complex

in themselves, are in the function of the

process of de-socialisation. Only by the

re-introduction of the complexity of socialised management and collective re-appropriation of resources can technological

complexity in a world of escalating expropriation be given the perspective of universal sisterhood, equality and liberation.