_A talk given on the second day of the conference_ [Off the

Press](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/22-23-may-2014/program/) _held at

WORM, Rotterdam, on May 23, 2014. Also available

in[PDF](/images/2/28/Barok_2014_Communing_Texts.pdf "Barok 2014 Communing

Texts.pdf")._

I am going to talk about publishing in the humanities, including scanning

culture, and its unrealised potentials online. For this I will treat the

internet not only as a platform for storage and distribution but also as a

medium with its own specific means for reading and writing, and consider the

relevance of plain text and its various rendering formats, such as HTML, XML,

markdown, wikitext and TeX.

One of the main reasons why books today are downloaded and bookmarked but

hardly read is the fact that they may contain something relevant but they

begin at the beginning and end at the end; or at least we are used to treat

them in this way. E-book readers and browsers are equipped with fulltext

search functionality but the search for "how does the internet change the way

we read" doesn't yield anything interesting but the diversion of attention.

Whilst there are dozens of books written on this issue. When being insistent,

one easily ends up with a folder with dozens of other books, stucked with how

to read them. There is a plethora of books online, yet there are indeed mostly

machines reading them.

It is surely tempting to celebrate or to despise the age of artificial

intelligence, flat ontology and narrowing down the differences between humans

and machines, and to write books as if only for machines or return to the

analogue, but we may as well look back and reconsider the beauty of simple

linear reading of the age of print, not for nostalgia but for what we can

learn from it.

This perspective implies treating texts in their context, and particularly in

the way they commute, how they are brought in relations with one another, into

a community, by the mere act of writing, through a technique that have

developed over time into what we have came to call _referencing_. While in the

early days referring to texts was practised simply as verbal description of a

referred writing, over millenia it evolved into a technique with standardised

practices and styles, and accordingly: it gained _precision_. This precision

is however nothing machinic, since referring to particular passages in other

texts instead of texts as wholes is an act of comradeship because it spares

the reader time when locating the passage. It also makes apparent that it is

through contexts that the web of printed books has been woven. But even though

referencing in its precision has been meant to be very concrete, particularly

the advent of the web made apparent that it is instead _virtual_. And for the

reader, laborous to follow. The web has shown and taught us that a reference

from one document to another can be plastic. To follow a reference from a

printed book the reader has to stand up, walk down the street to a library,

pick up the referred volume, flip through its pages until the referred one is

found and then follow the text until the passage most probably implied in the

text is identified, while on the web the reader, _ideally_ , merely moves her

finger a few milimeters. To click or tap; the difference between the long way

and the short way is obviously the hyperlink. Of course, in the absence of the

short way, even scholars are used to follow the reference the long way only as

an exception: there was established an unwritten rule to write for readers who

are familiar with literature in the respective field (what in turn reproduces

disciplinarity of the reader and writer), while in the case of unfamiliarity

with referred passage the reader inducts its content by interpreting its

interpretation of the writer. The beauty of reading across references was

never fully realised. But now our question is, can we be so certain that this

practice is still necessary today?

The web silently brought about a way to _implement_ the plasticity of this

pointing although it has not been realised as the legacy of referencing as we

know it from print. Today, when linking a text and having a particular passage

in mind, and even describing it in detail, the majority of links physically

point merely to the beginning of the text. Hyperlinks are linking documents as

wholes by default and the use of anchors in texts has been hardly thought of

as a _requirement_ to enable precise linking.

If we look at popular online journalism and its use of hyperlinks within the

text body we may claim that rarely someone can afford to read all those linked

articles, not even talking about hundreds of pages long reports and the like

and if something is wrong, it would get corrected via comments anyway. On the

internet, the writer is meant to be in more immediate feedback with the

reader. But not always readers are keen to comment and not always they are

allowed to. We may be easily driven to forget that quoting half of the

sentence is never quoting a full sentence, and if there ought to be the entire

quote, its source text in its whole length would need to be quoted. Think of

the quote _information wants to be free_ , which is rarely quoted with its

wider context taken into account. Even factoids, numbers, can be carbon-quoted

but if taken out of the context their meaning can be shaped significantly. The

reason for aversion to follow a reference may well be that we are usually

pointed to begin reading another text from its beginning.

While this is exactly where the practices of linking as on the web and

referencing as in scholarly work may benefit from one another. The question is

_how_ to bring them closer together.

An approach I am going to propose requires a conceptual leap to something we

have not been taught.

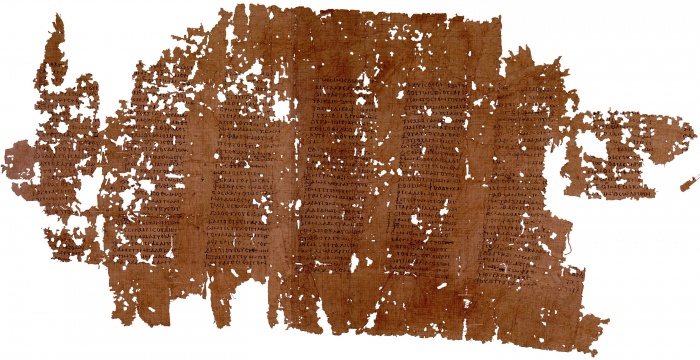

For centuries, the primary format of the text has been the page, a vessel, a

medium, a frame containing text embedded between straight, less or more

explicit, horizontal and vertical borders. Even before the material of the

page such as papyrus and paper appeared, the text was already contained in

lines and columns, a structure which we have learnt to perceive as a grid. The

idea of the grid allows us to view text as being structured in lines and

pages, that are in turn in hand if something is to be referred to. Pages are

counted as the distance from the beginning of the book, and lines as the

distance from the beginning of the page. It is not surprising because it is in

accord with inherent quality of its material medium -- a sheet of paper has a

shape which in turn shapes a body of a text. This tradition goes as far as to

the Ancient times and the bookroll in which we indeed find textual grids.

[](/File:Papyrus_of_Plato_Phaedrus.jpg)

A crucial difference between print and digital is that text files such as HTML

documents nor markdown documents nor database-driven texts did inherit this

quality. Their containers are simply not structured into pages, precisely

because of the nature of their materiality as media. Files are written on

memory drives in scattered chunks, beginning at point A and ending at point B

of a drive, continuing from C until D, and so on. Where does each of these

chunks start is ultimately independent from what it contains.

Forensic archaeologists would confirm that when a portion of a text survives,

in the case of ASCII documents it is not a page here and page there, or the

first half of the book, but textual blocks from completely arbitrary places of

the document.

This may sound unrelated to how we, humans, structure our writing in HTML

documents, emails, Office documents, even computer code, but it is a reminder

that we structure them for habitual (interfaces are rectangular) and cultural

(human-readability) reasons rather then for a technical necessity that would

stem from material properties of the medium. This distinction is apparent for

example in HTML, XML, wikitext and TeX documents with their content being both

stored on the physical drive and treated when rendered for reading interfaces

as single flow of text, and the same goes for other texts when treated with

automatic line-break setting turned off. Because line-breaks and spaces and

everything else is merely a number corresponding to a symbol in character set.

So how to address a section in this kind of document? An option offers itself

-- how computers do, or rather how we made them do it -- as a position of the

beginning of the section in the array, in one long line. It would mean to

treat the text document not in its grid-like format but as line, which merely

adapts to properties of its display when rendered. As it is nicely implied in

the animated logo of this event and as we know it from EPUBs for example.

In the case of 'reference-linking' we can refer to a passage by including the

information about its beginning and length determined by the character

position within the text (in analogy to _pp._ operator used for printed

publications) as well as the text version information (in printed texts served

by edition and date of publication). So what is common in printed text as the

page information is here replaced by the character position range and version.

Such a reference-link is more precise while addressing particular section of a

particular version of a document regardless of how it is rendered on an

interface.

It is a relatively simple idea and its implementation does not be seem to be

very hard, although I wonder why it has not been implemented already. I

discussed it with several people yesterday to find out there were indeed

already attempts in this direction. Adam Hyde pointed me to a proposal for

_fuzzy anchors_ presented on the blog of the Hypothes.is initiative last year,

which in order to overcome the need for versioning employs diff algorithms to

locate the referred section, although it is too complicated to be explained in

this setting.[1] Aaaarg has recently implemented in its PDF reader an option

to generate URLs for a particular point in the scanned document which itself

is a great improvement although it treats texts as images, thus being specific

to a particular scan of a book, and generated links are not public URLs.

Using the character position in references requires an agreement on how to

count. There are at least two options. One is to include all source code in

positioning, which means measuring the distance from the anchor such as the

beginning of the text, the beginning of the chapter, or the beginning of the

paragraph. The second option is to make a distinction between operators and

operands, and count only in operands. Here there are further options where to

make the line between them. We can consider as operands only characters with

phonetic properties -- letters, numbers and symbols, stripping the text from

operators that are there to shape sonic and visual rendering of the text such

as whitespaces, commas, periods, HTML and markdown and other tags so that we

are left with the body of the text to count in. This would mean to render

operators unreferrable and count as in _scriptio continua_.

_Scriptio continua_ is a very old example of the linear onedimensional

treatment of the text. Let's look again at the bookroll with Plato's writing.

Even though it is 'designed' into grids on a closer look it reveals the lack

of any other structural elements -- there are no spaces, commas, periods or

line-breaks, the text is merely one flow, one long line.

_Phaedrus_ was written in the fourth century BC (this copy comes from the

second century AD). Word and paragraph separators were reintroduced much

later, between the second and sixth century AD when rolls were gradually

transcribed into codices that were bound as pages and numbered (a dramatic

change in publishing comparable to digital changes today).[2]

'Reference-linking' has not been prominent in discussions about sharing books

online and I only came to realise its significance during my preparations for

this event. There is a tremendous amount of very old, recent and new texts

online but we haven't done much in opening them up to contextual reading. In

this there are publishers of all 'grounds' together.

We are equipped to treat the internet not only as repository and library but

to take into account its potentials of reading that have been hiding in front

of our very eyes. To expand the notion of hyperlink by taking into account

techniques of referencing and to expand the notion of referencing by realising

its plasticity which has always been imagined as if it is there. To mesh texts

with public URLs to enable entaglement of referencing and hyperlinks. Here,

open access gains its further relevance and importance.

Dušan Barok

_Written May 21-23, 2014, in Vienna and Rotterdam. Revised May 28, 2014._

Notes

1. ↑ Proposals for paragraph-based hyperlinking can be traced back to the work of Douglas Engelbart, and today there is a number of related ideas, some of which were implemented on a small scale: fuzzy anchoring, 1(http://hypothes.is/blog/fuzzy-anchoring/); purple numbers, 2(http://project.cim3.net/wiki/PMWX_White_Paper_2008); robust anchors, 3(http://github.com/hypothesis/h/wiki/robust-anchors); _Emphasis_ , 4(http://open.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/01/11/emphasis-update-and-source); and others 5(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragment_identifier#Proposals). The dependence on structural elements such as paragraphs is one of their shortcoming making them not suitable for texts with longer paragraphs (e.g. Adorno's _Aesthetic Theory_ ), visual poetry or computer code; another is the requirement to store anchors along the text.

2. ↑ Works which happened not to be of interest at the time ceased to be copied and mostly disappeared. On the book roll and its gradual replacement by the codex see William A. Johnson, "The Ancient Book", in _The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology_ , ed. Roger S. Bagnall, Oxford, 2009, pp 256-281, 6(http://google.com/books?id=6GRcLuc124oC&pg=PA256).

Addendum (June 9)

Arie Altena wrote a [report from the

panel](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/off-the-press-report-day-

ii/) published on the website of Digital Publishing Toolkit initiative,

followed by another [summary of the

talk](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/dusan-barok-digital-imprint-

the-motion-of-publishing/) by Irina Enache.

The online repository Aaaaarg [has

introduced](http://twitter.com/aaaarg/status/474717492808413184) the

reference-link function in its document viewer, see [an

example](http://aaaaarg.fail/ref/60090008362c07ed5a312cda7d26ecb8#0.102).

Sollfrank & Mars

Public Library

2013

Marcell Mars

Public Library

Berlin, 1 February 2013

[00:13]

Public Library is the concept, the idea, to encourage people to become a

librarian, where a librarian is a person which can allow access to books – and

also which has a catalogue or index, so that it's searchable. [00:32] And the

person, the human being, can communicate, can talk with others who are

interested in that catalogue of books. [00:43] And then when you have a

librarian, and you have a lot of librarians, you have a Public Library,

because we have access to books, we have a catalogue, and we have a librarian.

That's the basic set up. [00:55] And in order to really work, in practice, we

need to introduce a set of tools which are easy to use, like Calibre, for

example, for book management. [01:07] And then also some part of that set up

should be also developed because at the moment, because of the configuration

of the routers, IP addresses and other things, it's not that easy to share

your local library which you have on your laptop with the world. [01:30] So we

also provide... When I say ‘we,’ it's a small team, at the moment, of

developers who try to address that problem. [01:38] We don't need to reinvent

the public library. It's invented, and it should be just maintained. [01:47]

The old-school public libraries – they are in decline because of many reasons.

And when it comes to the digital networks, the digital books, it's almost like

the worst position. [01:59] For example, public libraries in the US, they are

not allowed to buy digital books, for example from Penguin. So even when they

want to buy, it's not that they are getting them, it's that they can't buy the

books. [02:16] By the current legal regulation, it's considered as illegal – a

million of books, or even more, are unavailable, and I think that these books

should be really available. [02:29] And it doesn't really matter how it got on

Internet – did it come from a graphic designer who is preparing that for

print, or if it was uploaded somewhere from the author of the book (that is

also very common, especially in humanities), or if it was digitised anywhere.

[02:50] So these are the books which we have, and we can't be blinded, they

are here. The practice at the moment is almost like trying to find a

prostitute or something, so when you want to get a book online you need to get

onto the websites with advertisements for casinos, for porn and things like

that. [03:14] I don't think that the library should be like that.

[03:18]

Book Management

[03:22]

What we are trying to provide is just suggesting what kind of book management

software they can use, and also what kind of new software tools they can

install in order to easily get the messy directory into the directory of

metadata which Calibre can recognise – and then you can just use Calibre. The

next step is if you can share your local library with the world. [03:52] You

need something like a management software where it's easy to see who are the

authors, what the titles, publishers and all of the metadata – and it's

accessible from the outside.

[04:08]

Calibre

[04:12]

Calibre is a book management software. It's developed by Kovid Goyal, a

software developer. [04:22] It's a free software, open source, and it started

like many other free software projects. It started as a small tool to solve

very particular small problems. [04:31] But then, because it was useful, it

got more and more users, and then Kovid started to develop it more into a

proper, big book management software. At the moment it has more that 10

million registered users who are running that. [04:52] It does so many things

for book management. It's really ‘the’ software tool... If you have an

e-reader, for example, it recognises your e-reader, it registers it inside of

Calibre and then you can easily just transfer the books. [05:08] Also for

years there was a big problem of file formats. So for example, Amazon, in

order to keep their monopoly in that area, they wouldn't support EPUB or PDF.

And then if you got your book somewhere – if you bought it or just downloaded

from the Internet, you wouldn't be able to read it on your reader. [05:31]

Then Calibre was just developing the converter tools. And it was all in one

package, so that Calibre just became the tool for book management. [05:43] It

has a web server as a part of it. So in a local area network – if you just

start that web server and you are running a local area network, it can have a

read-only searchable access to your local library, to your books, and it can

search by any of these metadata.

[06:05]

Tools Around Calibre

[06:09]

I developed a software which I call Let's Share Books, which is super small

compared to Calibre. It just allows you, with one click, to get your library

shared on the Internet. [06:24] So that means that you get a public URL, which

says something like www some-number dot memoryoftheworld dot net, and that is

the temporary public URL. You can send it to anyone in the world. [06:37] And

while you are running your local web server and share books, it would just

serve these books to the Internet. [06:45] I also set up a web chat – kind of

a room where people can talk to each other, chat to each other. [06:54] So

it’s just, trying to develop tools around Calibre, which is mostly for one

person, for one librarian – to try to make some kind of ecosystem for a lot of

librarians where they can meet with their readers or among themselves, and

talk about the books which they love to read and share. [07:23] It’s mostly

like a social networking around the books, where we use the idea and tradition

of the public library. [07:37] In order to get there I needed to set up a

server which only does routing. So with my software I don’t know which books

are transferred, anything. It’s just like a router. [07:56] You can do that

also if you have control of your router, or what we usually call modem, so the

device which you use to get to the Internet. But that is quite hard to hack,

just hackers know how to do that. [08:13] So I just made a server on the

Internet which you can use with one click, and it just routes the traffic

between you, if you’re a librarian, and your users, readers. So that’s that

easy.

[08:33]

Librarians

[08:38] It’s super easy to become a librarian, and that is what we should

celebrate. It’s not that the only librarians which we have were the librarians

who were the only ones wanting to become a librarian. [08:54] So lots of

people want to be a librarian, and lots of people are librarians whenever they

have a chance. [09:00] So you would probably recommend me some books which you

like. I’ll recommend you some books which I like. So I think we should

celebrate that now it’s super easy that anyone can be a librarian. [09:11] And

of course, we will still need professional librarians in order to push forward

the whole field. But that goes, again, in collaboration with software

engineers, information architectes, whatever… [09:26] It’s so easy to have

that, and the benefits of that are so great, that there is no reason why not

to do that, I would say.

[09:38]

Functioning

[09:43]

If you want to share your collection then you need to install at the moment

Calibre, and Let’s Share Books software, which I wrote. But also you can – for

example, there is a Calibre plugin for Aaaaarg, so if you use Calibre… from

Calibre you can search Aaaaarg, you can download books from Aaaaarg, you can

also change the metadata and upload the metadata up to Aaaaarg.

[10:13]

Repositories

[10:17]

At the moment the biggest repository for the books, in order to download and

make your catalogue, is Library Genesis. It’s around 900,000 books. It’s

libgen.info, libgen.org. And it’s a great project. [10:33] It’s done by some

Russian hackers, who also allow anyone to download all of that. It’s 9

Terabytes of books, quite some chunk of hard disks which you need for that.

[10:47] And you can also download PHP, the back end of the website and the

MySQL database (a thumb of the MySQL database), so you can run your own

Library Genesis. That’s one of the ways how you can do that. [11:00] You can

also go and join Aaaaarg.org, where it is also not just about downloading

books and uploading books, it’s also about communication and interpretation of

making, different issues and catalogues. [11:14] It’s a community of book

lovers who like to share knowledge, and who add quite a lot of value around

the books by doing that. [11:26] And then there is… you can use Calibre and

Let’s Share Books. It’s just one of these complimentary tools. So it’s not

really that Calibre and Let’s Share Books is the only way how you can today

share books.

[11:45]

Goal

[11:50]

What we do also has a non-hidden agenda for fighting for the public library. I

would say that most of the people we know, even the authors, they all

participate in the huge, massive Public Library – which we don’t call Public

Library, but usually just trying to hide that we are using that because we are

afraid of the restrictive regime. [12:20] So I don’t see a reason why we

should shut down such a great idea and great implementation – a great resource

which we have all around the world. [12:30] So it’s just an attempt to map all

of these projects and to try to improve them. Because, in order to get it into

the right shape, we need to improve the metadata. [12:47] Open Library, a

project which started also with Aaron Swartz, has 20 millions items, and we

use it. There is a basedata.org which connects the hash files, the MD5 hashes,

with the Open Library ID. And we try to contribute to Open Library as much as

possible. [13:10] So with very few people, around 5 people, we can improve it

so much that it will be for a billion of users a great Public Library, and at

the same time we can have millions of librarians, which we never had before.

So that’s the idea. [13:35] The goal is just to keep the Public Library. If we

didn’t screw up the whole situation with the Public Library, probably we’d

just try to add a little bit of new software, and new ways that we can read

the books. [13:53] But at the moment [it’s] super important actually to keep

this infrastructure running, because this super important infrastructure for

the access to knowledge is now under huge threat.

[14:09]

Copyright

[14:13]

I just think that it’s completely inappropriate – that copyright law is

completely inappropriate for the Public Library. I don’t know about other

cases, but in terms of Public Library it’s absolutely inappropriate. [14:29]

We should find the new ways of how to reward the ones who are adding value to

sharing knowledge. First authors, then anyone who is involved in public

libraries, like librarians, software engineers – so everyone who is involved

in that ecosystem should be rewarded, because it’s a great thing, it’s a

benefit for the society. [15:03] If this kind of things happens, so if the law

which regulates this blocks and doesn’t let that field blossom, it’s something

wrong with that law. [15:16] It’s getting worse and worse, so I don’t know for

how long we should wait, because while we’re waiting it’s getting worse.

[15:24] I don’t care. And I think that I can say that because I’m an artist.

Because all of these laws are made saying that they are representing art, they

are representing the interest of artists. I’m an artist. They don’t really

represent my interests. [15:46] I think that it should be taken over by the

artists. And if there are some artists who disagree – great, let’s have a

discussion.

[15:58]

Civil Disobedience

[16:03]

In the possibilities of civil disobedience – which are done also by

institutions, not just by individuals – and I think that in such clear cases

like the Public Library it’s easy. [16:17] So I think that what I did in this

particular case is nothing really super smart – it’s just reducing this huge

issue to something which is comprehensible, which is understandable for most

of the people. [16:31] There is no one really who doesn’t understand what

public library is. And if you say to anyone in the world, saying, like hey, no

more public libraries, hey, no books anymore, no books for the poor people. We

are just giving up on something which we almost consensually accepted through

the whole world. [16:55] And I think that in such clear cases, I’m really

interested [in] what institutions could do, like Transmediale. I’m now in

[Akademie] Schloss Solitude, I also proposed to make a server with a Public

Library. If you invest enough it’s a million of books, it’s a great library.

[17:16] And of course they are scared. And I think that the system will never

really move if people are not brave. [17:26] I’m not really trying to

encourage people to do something where no one could really understand, you

know, and you need expertise or whatever. [17:37] In my opinion this is the

big case. And if Transmediale or any other art institution is playing with

that, and showing that – let’s see how far away we can support this kind of

things. [17:56] The other issue which I am really interested in is what is the

infrastructure, who is running the infrastructures, and what kind of

infrastructures are happen in between these supposedly avant-garde

institutions, or something. [08:12] So I’m really interested in raising these

issues.

[18:17]

Art Project

[18:21]

Public Library is also an art project where… I would say that just in the same

way that corporations, by their legal status, can really kind of mess around

with different… they can’t be that much accountable and responsible – I think

that this is the counterpart. [18:44] So civil disobedience can use art just

the same way that corporations can use their legal status. [18:51] When I was

invited as a curator and artist to curate the HAIP Festival in Ljubljana, I

was already quite into the topic of sharing access to knowledge. And then I

came up with this idea and everybody liked it and everybody was enthusiastic.

It's one of these ideas where you can see that it’s great, there is no one

really who would oppose to that. [19:28] At the same time there was an

exhibition, Dear Art, curated by WHW, quite established curators. And then it

immediately became an art piece for that exhibition. Then I was invited here

to Transmediale, and have a couple of other invitations. [19:45] I think that

it also shows that art institutions are accepting that, they play with that

idea. And I think that this kind of projects – by having that acceptance it

becomes the issue, it becomes the problem of the whole arts establishment.

[20:10] So I think that if I do this in this way, and if there is a curator

who invites this kind of projects – so who invites Public Library into their

exhibition – it’s also showing their kind of readiness to fight for that

issue. [20:27] And if there are a number of art festivals, a number of art

exhibitions, who are supporting this kind of, lets say, civil disobedience,

that also shows something. [20:38] And I think that that kind of context

should be pushed into the confrontation, so it’s not anymore just playing “oh,

is it is ok, it is not? We should deal with all the complexity…” [20:57] There

is no real complexity here. That complexity is somewhere else, and in some

other step we should take care of that. But this is an art piece, it’s a well

established art piece. [21:11] If you make a Public Library, I'm fine, I’m

sacrificing for taking the responsibility. But you shouldn't melt down that

art piece, I think. [21:26] And I feel super stupid that such a simple concept

should be, in 2013, articulated to whom? In many ways it’s like playing dummy,

I play dummy. It’s like, why should I? [21:50] When we started to play in

Ljubljana like software developers we came up with so many great ideas of how

to use those resources. So it was immediately… just after couple of hours we

had tools – visualisations of that, a reader of Wikipedia which can embed any

page which is referred, as a reference, a quote. [22:17] It was immediately

obvious for anyone there and for anyone from the outside what a huge resource

is having a Public Library like that – and what’s the huge harm that we don’t

have it. [22:32] But still we need to play dummy, I need to play the artist’s

role, you know.