_A talk given at the [Shadow Libraries](http://www.sgt.gr/eng/SPG2096/)

symposium held at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) in

[Athens](/Athens "Athens"), 17 March 2018. Moderated by [Kenneth

Goldsmith](/Kenneth_Goldsmith "Kenneth Goldsmith") (UbuWeb) and bringing

together [Dusan Barok](/Dusan_Barok "Dusan Barok") (Monoskop), [Marcell

Mars](/Marcell_Mars "Marcell Mars") (Public Library), [Peter

Sunde](/Peter_Sunde "Peter Sunde") (The Pirate Bay), [Vicki

Bennett](/Vicki_Bennett "Vicki Bennett") (People Like Us), [Cornelia

Sollfrank](/Cornelia_Sollfrank "Cornelia Sollfrank") (Giving What You Don't

Have), and Prodromos Tsiavos, the event was part of the _[Shadow Libraries:

UbuWeb in Athens](http://www.sgt.gr/eng/SPG2018/) _programme organised by [Ilan

Manouach](/Ilan_Manouach "Ilan Manouach"), Kenneth Goldsmith and the Onassis

Foundation._

This is the first time that I was asked to talk about Monoskop as a _shadow

library_.

What are shadow libraries?

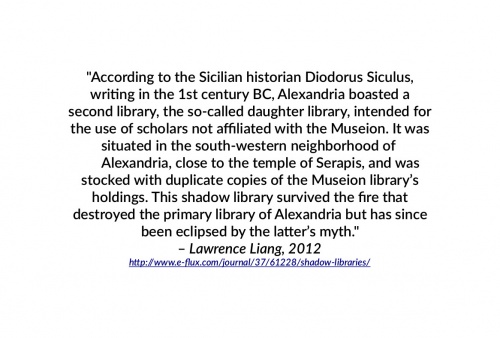

[Lawrence Liang](/Lawrence_Liang "Lawrence Liang") wrote a think piece for _e-

flux_ a couple of years ago,

in response to the closure of Library.nu, a digital library that had operated

from 2004, first as Ebooksclub, later as Gigapedia.

He wrote that:

[](http://www.e-flux.com/journal/37/61228

/shadow-libraries/)

In the essay, he moves between identifying Library.nu as digital Alexandria

and as its shadow.

In this account, even large libraries exist in the shadows cast by their

monumental precedessors.

There’s a lineage, there’s a tradition.

Almost everyone and every institution has a library, small or large.

They’re not necessarily Alexandrias, but they strive to stay relevant.

Take the University of Amsterdam where I now work.

University libraries are large, but they’re hardly _large enough_.

The publishing market is so huge that you simply can’t keep up with all the

niche little disciplines.

So either you have to wait days or weeks for a missing book to be ordered

somewhere.

Or you have some EBSCO ebooks.

And most of the time if you’re searching for a book title in the catalogue,

all you get are its reviews in various journals the library subscribes to.

So my colleagues keep asking me.

Dušan, where do I find this or that book?

You need to scan through dozens of texts, check one page in that book, table

of contents of another book, read what that paper is about.

[](/Digital_libraries#Libraries

"Digital libraries#Libraries")

Or scrapes it from somewhere, since most books today are born digital and live

their digital lives.

...

Digital libraries need to be creative.

They don’t just preserve and circulate books.

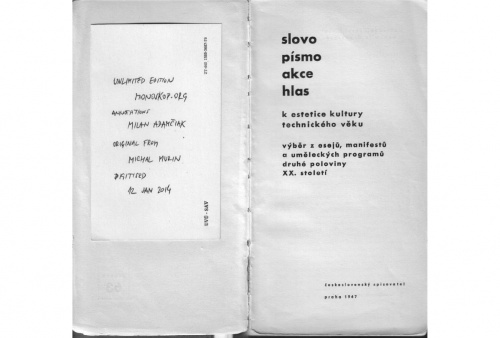

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=10262)

They engage in extending print runs, making new editions, readily

reproducible, unlimited editions.

[](https://monoskop.org/images/d/de/Hirsal_Josef_Groegerova_Bohumila_eds_Slovo_pismo_akce_hlas.pdf#page=87)

This one comes with something extra. Isn’t this beautiful? You can read along

someone else.

In this case we know these annotations come from the Slovak avant-garde visual

poet and composer [Milan Adamciak](/Milan_Adamciak "Milan Adamciak").

[](/Milan_Adamciak

"Milan Adamciak")

...standing in the middle.

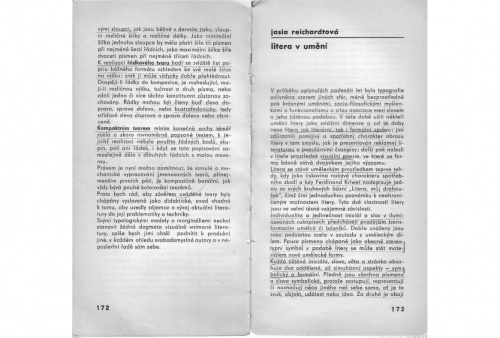

A couple of pages later...

[](https://monoskop.org/images/d/de/Hirsal_Josef_Groegerova_Bohumila_eds_Slovo_pismo_akce_hlas.pdf#page=117)

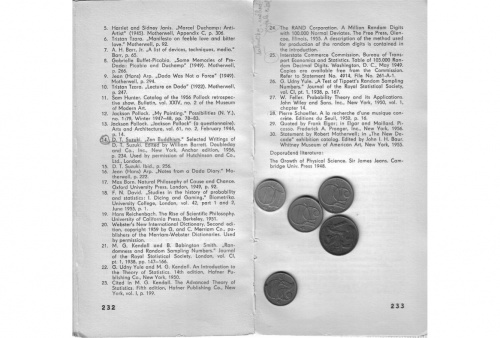

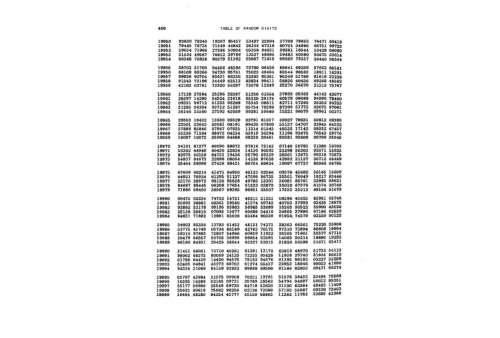

...you can clearly see how he found out about a book containing one million

random digits [see note 24 on the image]. The strangest book.

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=5780)

He was still alive when we put it up on Monoskop, and could experience it.

...

Digital libraries may seem like virtual, grey places, nonplaces.

But these little chance encounters happen all the time there.

There are touches. There are traces. There are many hands involved, visible

hands.

They join writers’ hands and help creating new, unlimited editions.

They may be off Google, but for many, especially younger generation these are

the places to go to learn, to share.

Rather than in a shadow, they are out in the open, in plain sight.

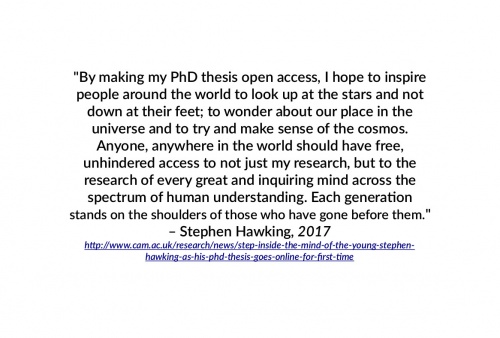

[](http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news

/step-inside-the-mind-of-the-young-stephen-hawking-as-his-phd-thesis-goes-

online-for-first-time)

This made rounds last year.

As scholars, as authors, we have reasons to have our works freely accessible

by everyone.

We do it for feedback, for invites to lecture, for citations.

Sounds great.

So when after long two, three, four, five years I have my manuscript ready,

where will I go?

Will I go to an established publisher or an open access press?

Will I send it to MIT Press or Open Humanities Press?

Traditional publishers have better distribution, and they often have a strong

brand.

It’s often about career moves and bios, plans A’s and plan B’s.

There are no easy answers, but one can always be a little inventive.

In the end, one should not feel guilty for publishing with MIT Press.

But at the same time, one should neither feel guilty for scanning and sharing

such a book with others.

...

You know, there’s fighting, there are court cases.

[Aaaaarg](/Aaaaarg "Aaaaarg"), a digital library run by our dear friend [Sean

Dockray](/Sean_Dockray "Sean Dockray"), is facing a Canadian publisher.

Open Library is now facing the Authors Guild for lending scanned books

deaccessioned from libraries.

They need our help, our support.

But collisions of interests can be productive.

This is what our beloved _Cabinet_ magazine did when they found their PDFs

online.

They converted all their articles into HTML and put them online.

The most beautiful takedown request we have ever received.

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=16598)

So what is at stake? What are these digital books?

They are poor versions of print books.

They come with no binding, no paper, no weight.

They come as PDFs, EPUBs, JPEGs in online readers, they come as HTML.

By the way, HTML is great, you can search it, copy, save it, it’s lightweight,

it’s supported by all browsers, footnotes too, you can adapt its layout

easily.

That’s completely fine for a researcher.

As a researcher, you just need source code:

you need plain text, page numbers, images, working footnotes, relevant data

and code.

_Data and code_ as well:

this is where online companions to print books come in,

you want to publish your research material,

your interviews, spreadsheets, software you made.

...

Here we distinguish between researchers and readers.

As _readers_ we will always build our beautiful libraries at home, and

elsewhere,

filled with books and... and external harddrives.

...

There may be _no contradiction_ between the existence of a print book in

stores and the existence of its free digital version.

So what we’ve been asking for is access, basic access. The access to culture

and knowledge for research, educational, noncommercial purposes. A low budget,

poor bandwidth access. Access to badly OCR’d ebooks with grainy images. Access

to culture and knowledge _light_.

Thank you.

Dusan Barok

_Written on 16-17 March 2018 in Athens and Amsterdam. Published online on 21

March 2018._

Bodo

In the Name of Humanity

2016

# In the Name of Humanity

By [Balazs Bodo](https://limn.it/researchers/bodo/)

As I write this in August 2015, we are in the middle of one of the worst

refugee crises in modern Western history. The European response to the carnage

beyond its borders is as diverse as the continent itself: as an ironic

contrast to the newly built barbed-wire fences protecting the borders of

Fortress Europe from Middle Eastern refugees, the British Museum (and probably

other museums) are launching projects to “protect antiquities taken from

conflict zones” (BBC News 2015). We don’t quite know how the conflict

artifacts end up in the custody of the participating museums. It may be that

asylum seekers carry such antiquities on their bodies, and place them on the

steps of the British Museum as soon as they emerge alive on the British side

of the Eurotunnel. But it is more likely that Western heritage institutions,

if not playing Indiana Jones in North Africa, Iraq, and Syria, are probably

smuggling objects out of war zones and buying looted artifacts from the

international gray/black antiquities market to save at least some of them from

disappearing in the fortified vaults of wealthy private buyers (Shabi 2015).

Apparently, there seems to be some consensus that artifacts, thought to be

part of the common cultural heritage of humanity, cannot be left in the hands

of those collectives who own/control them, especially if they try to destroy

them or sell them off to the highest bidder.

The exact limits of expropriating valuables in the name of humanity are

heavily contested. Take, for example, another group of self-appointed

protectors of culture, also collecting and safeguarding, in the name of

humanity, valuable items circulating in the cultural gray/black markets. For

the last decade Russian scientists, amateur librarians, and volunteers have

been collecting millions of copyrighted scientific monographs and hundreds of

millions of scientific articles in piratical shadow libraries and making them

freely available to anyone and everyone, without any charge or limitation

whatsoever (Bodó 2014b; Cabanac 2015; Liang 2012). These pirate archivists

think that despite being copyrighted and locked behind paywalls, scholarly

texts belong to humanity as a whole, and seek to ensure that every single one

of us has unlimited and unrestricted access to them.

The support for a freely accessible scholarly knowledge commons takes many

different forms. A growing number of academics publish in open access

journals, and offer their own scholarship via self-archiving. But as the data

suggest (Bodó 2014a), there are also hundreds of thousands of people who use

pirate libraries on a regular basis. There are many who participate in

courtesy-based academic self-help networks that provide ad hoc access to

paywalled scholarly papers (Cabanac 2015).[1] But a few people believe that

scholarly knowledge could and should be liberated from proprietary databases,

even by force, if that is what it takes. There are probably no more than a few

thousand individuals who occasionally donate a few bucks to cover the

operating costs of piratical services or share their private digital

collections with the world. And the number of pirate librarians, who devote

most of their time and energy to operate highly risky illicit services, is

probably no more than a few dozen. Many of them are Russian, and many of the

biggest pirate libraries were born and/or operate from the Russian segment of

the Internet.

The development of a stable pirate library, with an infrastructure that

enables the systematic growth and development of a permanent collection,

requires an environment where the stakes of access are sufficiently high, and

the risks of action are sufficiently low. Russia certainly qualifies in both

of these domains. However, these are not the only reasons why so many pirate

librarians are Russian. The Russian scholars behind the pirate libraries are

familiar with the crippling consequences of not having access to fundamental

texts in science, either for political or for purely economic reasons. The

Soviet intelligentsia had decades of experience in bypassing censors, creating

samizdat content distribution networks to deal with the lack of access to

legal distribution channels, and running gray and black markets to survive in

a shortage economy (Bodó 2014b). Their skills and attitudes found their way to

the next generation, who now runs some of the most influential pirate

libraries. In a culture, where the know-how of how to resist information

monopolies is part of the collective memory, the Internet becomes the latest

in a long series of tools that clandestine information networks use to build

alternative publics through the illegal sharing of outlawed texts.

In that sense, the pirate library is a utopian project and something more.

Pirate librarians regard their libraries as a legitimate form of resistance

against the commercialization of public resources, the (second) enclosure

(Boyle 2003) of the public domain. Those handful who decide to publicly defend

their actions, speak in the same voice, and tell very similar stories. Aaron

Swartz was an American hacker willing to break both laws and locks in his

quest for free access. In his 2008 “Guerilla Open Access Manifesto” (Swartz

2008), he forcefully argued for the unilateral liberation of scholarly

knowledge from behind paywalls to provide universal access to a common human

heritage. A few years later he tried to put his ideas into action by

downloading millions of journal articles from the JSTOR database without

authorization. Alexandra Elbakyan is a 27-year-old neurotechnology researcher

from Kazakhstan and the founder of Sci-hub, a piratical collection of tens of

millions of journal articles that provides unauthorized access to paywalled

articles to anyone without an institutional subscription. In a letter to the

judge presiding over a court case against her and her pirate library, she

explained her motives, pointing out the lack of access to journal articles.[2]

Elbakyan also believes that the inherent injustices encoded in current system

of scholarly publishing, which denies access to everyone who is not

willing/able to pay, and simultaneously denies payment to most of the authors

(Mars and Medak 2015), are enough reason to disregard the fundamental IP

framework that enables those injustices in the first place. Other shadow

librarians expand the basic access/injustice arguments into a wider critique

of the neoliberal political-economic system that aims to commodify and

appropriate everything that is perceived to have value (Fuller 2011; Interview

with Dusan Barok 2013; Sollfrank 2013).

Whatever prompts them to act, pirate librarians firmly believe that the fruits

of human thought and scientific research belong to the whole of humanity.

Pirates have the opportunity, the motivation, the tools, the know-how, and the

courage to create radical techno-social alternatives. So they resist the

status quo by collecting and “guarding” scholarly knowledge in libraries that

are freely accessible to all.

Both the curators of the British Museum and the pirate librarians claim to

save the common heritage of humanity, but any similarities end there. Pirate

libraries have no buildings or addresses, they have no formal boards or

employees, they have no budgets to speak of, and the resources at their

disposal are infinitesimal. Unlike the British Museum or libraries from the

previous eras, pirate libraries were born out of lack and despair. Their

fugitive status prevents them from taking the traditional paths of

institutionalization. They are nomadic and distributed by design; they are _ad

hoc_ and tactical, pseudonymous and conspiratory, relying on resources reduced

to the absolute minimum so they can survive under extremely hostile

circumstances.

Traditional collections of knowledge and artifacts, in their repurposed or

purpose-built palaces, are both the products and the embodiments of the wealth

and power that created them. Pirate libraries don’t have all the symbols of

transubstantiated might, the buildings, or all the marble, but as

institutions, they are as powerful as their more established counterparts.

Unlike the latter, whose claim to power was the fact of ownership and the

control over access and interpretation, pirates’ power is rooted in the

opposite: in their ability to make ownership irrelevant, access universal, and

interpretation democratic.

This is the paradox of the total piratical archive: they collect enormous

wealth, but they do not own or control any of it. As an insurance policy

against copyright enforcement, they have already given everything away: they

release their source code, their databases, and their catalogs; they put up

the metadata and the digitalized files on file-sharing networks. They realize

that exclusive ownership/control over any aspects of the library could be a

point of failure, so in the best traditions of archiving, they make sure

everything is duplicated and redundant, and that many of the copies are under

completely independent control. If we disregard for a moment the blatantly

illegal nature of these collections, this systematic detachment from the

concept of ownership and control is the most radical development in the way we

think about building and maintaining collections (Bodó 2015).

Because pirate libraries don’t own anything, they have nothing to lose. Pirate

librarians, on the other hand, are putting everything they have on the line.

Speaking truth to power has a potentially devastating price. Swartz was caught

when he broke into an MIT storeroom to download the articles in the JSTOR

database.[3] Facing a 35-year prison sentence and $1 million in fines, he

committed suicide.[4] By explaining her motives in a recent court filing,[5]

Elbakyan admitted responsibility and probably sealed her own legal and

financial fate. But her library is probably safe. In the wake of this lawsuit,

pirate libraries are busy securing themselves: pirates are shutting down

servers whose domain names were confiscated and archiving databases, again and

again, spreading the illicit collections through the underground networks

while setting up new servers. It may be easy to destroy individual

collections, but nothing in history has been able to destroy the idea of the

universal library, open for all.

For the better part of that history, the idea was simply impossible. Today it

is simply illegal. But in an era when books are everywhere, the total archive

is already here. Distributed among millions of hard drives, it already is a

_de facto_ common heritage. We are as gods, and might as well get good at

it.[6]

## About the author

**Bodo Balazs,** PhD, is an economist and piracy researcher at the Institute

for Information Law (IViR) at the University of Amsterdam. [More

»](https://limn.it/researchers/bodo/)

## Footnotes

[1] On such fora, one can ask for and receive otherwise out-of-reach

publications through various reddit groups such as

[r/Scholar](https://www.reddit.com/r/Scholar) and using certain Twitter

hashtags like #icanhazpdf or #pdftribute.

[2] Elsevier Inc. et al v. Sci-Hub et al, New York Southern District Court,

Case No. 1:15-cv-04282-RWS

[3] While we do not know what his aim was with the article dump, the

prosecution thought his Manifesto contained the motives for his act.

[4] See _United States of America v. Aaron Swartz_ , United States District

Court for the District of Massachusetts, Case No. 1:11-cr-10260

[5] Case 1:15-cv-04282-RWS Document 50 Filed 09/15/15, available at

[link](https://www.unitedstatescourts.org/federal/nysd/442951/).

[6] I of course stole this line from Stewart Brand (1968), the editor of the

Whole Earth catalog, who, in return, claims to have been stolen it from the

British anthropologist Edmund Leach. See

[here](http://www.wholeearth.com/issue/1010/article/195/we.are.as.gods) for

the details.

## Bibliography

BBC News. “British Museum ‘Guarding’ Object Looted from Syria. _BBC News,_

June 5. Available at [link](http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-

arts-33020199).

Bodó, B. 2015. “Libraries in the Post-Scarcity Era.” In _Copyrighting

Creativity_ , edited by H. Porsdam (pp. 75–92). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

———. 2014a. “In the Shadow of the Gigapedia: The Analysis of Supply and Demand

for the Biggest Pirate Library on Earth.” In _Shadow Libraries_ , edited by J.

Karaganis (forthcoming). New York: American Assembly. Available at

[link](http://ssrn.com/abstract=2616633).

———. 2014b. “A Short History of the Russian Digital Shadow Libraries.” In

Shadow Libraries, edited by J. Karaganis (forthcoming). New York: American

Assembly. Available at [link](http://ssrn.com/abstract=2616631).

Boyle, J. 2003. “The Second Enclosure Movement and the Construction of the

Public Domain.” _Law and Contemporary Problems_ 66:33–42. Available at

[link](http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.470983).

Brand, S. 1968. _Whole Earth Catalog,_ Menlo Park, California: Portola

Institute.

Cabanac, G. 2015. “Bibliogifts in LibGen? A Study of a Text‐Sharing Platform

Driven by Biblioleaks and Crowdsourcing.” _Journal of the Association for

Information Science and Technology,_ Online First, 27 March 2015 _._

Fuller, M. 2011. “In the Paradise of Too Many Books: An Interview with Sean

Dockray.” _Metamute._ Available at

[link](http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/paradise-too-many-books-

interview-sean-dockray).

Interview with Dusan Barok. 2013. _Neural_ 10–11.

Liang, L. 2012. “Shadow Libraries.” _e-flux._ Available at

[link](http://www.e-flux.com/journal/shadow-libraries/).

Mars, M., and Medak, T. 2015. “The System of a Takedown: Control and De-

commodification in the Circuits of Academic Publishing.” Unpublished

manuscript.

Shabi, R. 2015. “Looted in Syria–and Sold in London: The British Antiques

Shops Dealing in Artefacts Smuggled by ISIS.” _The Guardian,_ July 3.

Available at [link](http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/03/antiquities-

looted-by-isis-end-up-in-london-shops).

Sollfrank, C. 2013. “Giving What You Don’t Have: Interviews with Sean Dockray

and Dmytri Kleiner.” _Culture Machine_ 14:1–3.

Swartz, A. 2008. “Guerilla Open Access Manifesto.” Available at

[link](https://archive.org/stream/GuerillaOpenAccessManifesto/Goamjuly2008_djvu.txt).