_A talk given at the [Shadow Libraries](http://www.sgt.gr/eng/SPG2096/)

symposium held at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) in

[Athens](/Athens "Athens"), 17 March 2018. Moderated by [Kenneth

Goldsmith](/Kenneth_Goldsmith "Kenneth Goldsmith") (UbuWeb) and bringing

together [Dusan Barok](/Dusan_Barok "Dusan Barok") (Monoskop), [Marcell

Mars](/Marcell_Mars "Marcell Mars") (Public Library), [Peter

Sunde](/Peter_Sunde "Peter Sunde") (The Pirate Bay), [Vicki

Bennett](/Vicki_Bennett "Vicki Bennett") (People Like Us), [Cornelia

Sollfrank](/Cornelia_Sollfrank "Cornelia Sollfrank") (Giving What You Don't

Have), and Prodromos Tsiavos, the event was part of the _[Shadow Libraries:

UbuWeb in Athens](http://www.sgt.gr/eng/SPG2018/) _programme organised by [Ilan

Manouach](/Ilan_Manouach "Ilan Manouach"), Kenneth Goldsmith and the Onassis

Foundation._

This is the first time that I was asked to talk about Monoskop as a _shadow

library_.

What are shadow libraries?

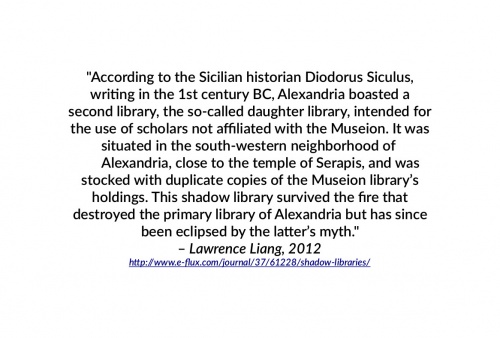

[Lawrence Liang](/Lawrence_Liang "Lawrence Liang") wrote a think piece for _e-

flux_ a couple of years ago,

in response to the closure of Library.nu, a digital library that had operated

from 2004, first as Ebooksclub, later as Gigapedia.

He wrote that:

[](http://www.e-flux.com/journal/37/61228

/shadow-libraries/)

In the essay, he moves between identifying Library.nu as digital Alexandria

and as its shadow.

In this account, even large libraries exist in the shadows cast by their

monumental precedessors.

There’s a lineage, there’s a tradition.

Almost everyone and every institution has a library, small or large.

They’re not necessarily Alexandrias, but they strive to stay relevant.

Take the University of Amsterdam where I now work.

University libraries are large, but they’re hardly _large enough_.

The publishing market is so huge that you simply can’t keep up with all the

niche little disciplines.

So either you have to wait days or weeks for a missing book to be ordered

somewhere.

Or you have some EBSCO ebooks.

And most of the time if you’re searching for a book title in the catalogue,

all you get are its reviews in various journals the library subscribes to.

So my colleagues keep asking me.

Dušan, where do I find this or that book?

You need to scan through dozens of texts, check one page in that book, table

of contents of another book, read what that paper is about.

[](/Digital_libraries#Libraries

"Digital libraries#Libraries")

Or scrapes it from somewhere, since most books today are born digital and live

their digital lives.

...

Digital libraries need to be creative.

They don’t just preserve and circulate books.

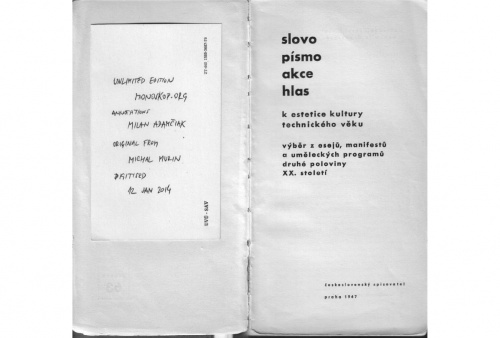

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=10262)

They engage in extending print runs, making new editions, readily

reproducible, unlimited editions.

[](https://monoskop.org/images/d/de/Hirsal_Josef_Groegerova_Bohumila_eds_Slovo_pismo_akce_hlas.pdf#page=87)

This one comes with something extra. Isn’t this beautiful? You can read along

someone else.

In this case we know these annotations come from the Slovak avant-garde visual

poet and composer [Milan Adamciak](/Milan_Adamciak "Milan Adamciak").

[](/Milan_Adamciak

"Milan Adamciak")

...standing in the middle.

A couple of pages later...

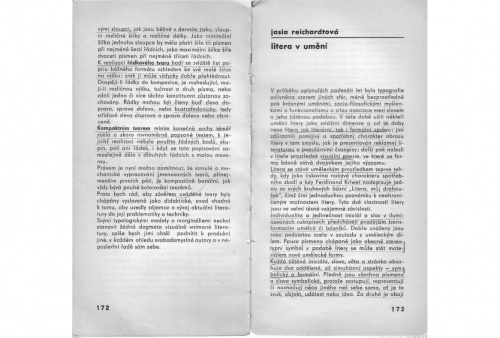

[](https://monoskop.org/images/d/de/Hirsal_Josef_Groegerova_Bohumila_eds_Slovo_pismo_akce_hlas.pdf#page=117)

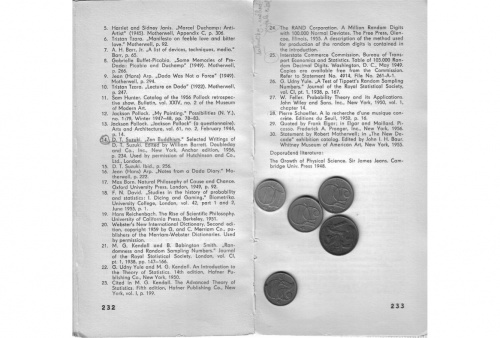

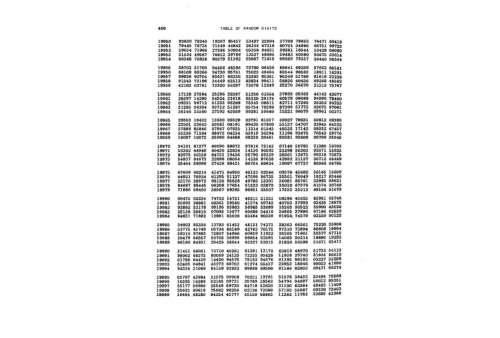

...you can clearly see how he found out about a book containing one million

random digits [see note 24 on the image]. The strangest book.

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=5780)

He was still alive when we put it up on Monoskop, and could experience it.

...

Digital libraries may seem like virtual, grey places, nonplaces.

But these little chance encounters happen all the time there.

There are touches. There are traces. There are many hands involved, visible

hands.

They join writers’ hands and help creating new, unlimited editions.

They may be off Google, but for many, especially younger generation these are

the places to go to learn, to share.

Rather than in a shadow, they are out in the open, in plain sight.

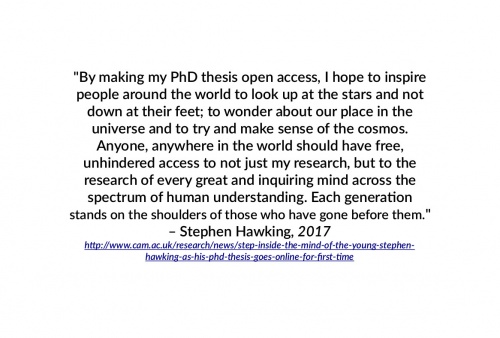

[](http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news

/step-inside-the-mind-of-the-young-stephen-hawking-as-his-phd-thesis-goes-

online-for-first-time)

This made rounds last year.

As scholars, as authors, we have reasons to have our works freely accessible

by everyone.

We do it for feedback, for invites to lecture, for citations.

Sounds great.

So when after long two, three, four, five years I have my manuscript ready,

where will I go?

Will I go to an established publisher or an open access press?

Will I send it to MIT Press or Open Humanities Press?

Traditional publishers have better distribution, and they often have a strong

brand.

It’s often about career moves and bios, plans A’s and plan B’s.

There are no easy answers, but one can always be a little inventive.

In the end, one should not feel guilty for publishing with MIT Press.

But at the same time, one should neither feel guilty for scanning and sharing

such a book with others.

...

You know, there’s fighting, there are court cases.

[Aaaaarg](/Aaaaarg "Aaaaarg"), a digital library run by our dear friend [Sean

Dockray](/Sean_Dockray "Sean Dockray"), is facing a Canadian publisher.

Open Library is now facing the Authors Guild for lending scanned books

deaccessioned from libraries.

They need our help, our support.

But collisions of interests can be productive.

This is what our beloved _Cabinet_ magazine did when they found their PDFs

online.

They converted all their articles into HTML and put them online.

The most beautiful takedown request we have ever received.

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=16598)

So what is at stake? What are these digital books?

They are poor versions of print books.

They come with no binding, no paper, no weight.

They come as PDFs, EPUBs, JPEGs in online readers, they come as HTML.

By the way, HTML is great, you can search it, copy, save it, it’s lightweight,

it’s supported by all browsers, footnotes too, you can adapt its layout

easily.

That’s completely fine for a researcher.

As a researcher, you just need source code:

you need plain text, page numbers, images, working footnotes, relevant data

and code.

_Data and code_ as well:

this is where online companions to print books come in,

you want to publish your research material,

your interviews, spreadsheets, software you made.

...

Here we distinguish between researchers and readers.

As _readers_ we will always build our beautiful libraries at home, and

elsewhere,

filled with books and... and external harddrives.

...

There may be _no contradiction_ between the existence of a print book in

stores and the existence of its free digital version.

So what we’ve been asking for is access, basic access. The access to culture

and knowledge for research, educational, noncommercial purposes. A low budget,

poor bandwidth access. Access to badly OCR’d ebooks with grainy images. Access

to culture and knowledge _light_.

Thank you.

Dusan Barok

_Written on 16-17 March 2018 in Athens and Amsterdam. Published online on 21

March 2018._

Dockray

The Scan and the Export

2010

the image, corrects the contrast, crops out the use

less bits, sharpens the text, and occasionally even

attempts to read it. All of this computation wants

to repress any traces of reading and scanning, with

the obvious goal of returning to the pure book, or

an even more Platonic form.

That purified, originary version of the text

might be the e-book. Publishers are occasionally

skipping the act of printing altogether and selling

the files themselves, such that the words reserved

for “

well-scanned”books ultimately describe ebooks: clean, searchable, small (i.e., file size). Al

though it is perfectly understandable for a reader

to prefer aligned text without smudges or other

markings where “

paper”is nothing but a pure,

bright white, this movement towards the clean has

its consequences. Distinguished as a form by the

fact that it is produced, distributed, and consumed

digitally, the e-book never leaves the factory.

A minimal gap is, however, created between

the file that the producer uses and the one that

the consumer uses— imagine the cultural chaos

if the typical way of distributing books were as

Word documents!— through the process of export

ing. Whereas scanning is a complex process and

material transformation (which includes exporting

at the very end), exporting is merely converting

formats. But however minor an act, this conver

sion is what puts a halt to the writing and turns

the file into a product for reading. It is also at this

stage that forms of “

digital rights management”ate

applied in order to restrict copying and printing of

the file.

Sharing and copying texts is as old as books

themselves— actually, one could argue that this is

almost a definition of the book— but computers

and the Internet have only accelerated this

activity. From transcription to tracing to photocopying

to scanning, the labour and material costs involved

in producing a copy has fallen to nothing in our

present digital file situation. Once the scan has

generated a digitized version of some kind, say a

PDF, it easily replicates and circulates. This is not

aberrant behaviour, either, but normative comput

er use: copy and paste are two of the first choices

in any contextual menu. Personal file storage has

slowly been migrating onto computer networks,

particularly with the growth of mobile devices, so

Sean Dockray

The Scan and the Export

The scan is an ambivalent image. It oscillates

back and forth: between a physical page and a

digital file, between one reader and another, be

tween an economy of objects and an economy of

data. Scans are failures in terms of quality, neither

as “

readable”as the original book nor the inevi

table ebook, always containing too much visual

information or too little.

Technically speaking, it is by scanning that

one can make a digital representation of a physical

object, such as a book. When a representation of

that representation (the image) appears on a digital

display device, it hovers like a ghost, one world

haunting another. But it is not simply the object

asserting itself in the milieu of light, informa

tion, and electricity. Much more is encoded in

the image: indexes of past readings and the act of

scanning itself.

An incomplete inventory of modifications to

the book through reading and other typical events

in the life of the thing: folded pages, underlines,

marginal notes, erasures, personal symbolic sys

tems, coffee spills, signatures, stamps, tears, etc.

Intimacy between reader and text marking the

pages, suggesting some distant future palimpsest in

which the original text has finally given way to a

mass of negligible marks.

Whereas the effects of reading are cumulative,

the scan is a singular event. Pages are spread and

pressed flat against a sheet of glass. The binding

stretches, occasionally to the point of breaking.

A camera driven by a geared down motor slides

slowly down the surface of the page. Slight move

ment by the person scanning (who is also a scan

ner; this is a man-machine performance) before

the scan is complete produces a slight motion blur,

the type goes askew, maybe a finger enters the

frame of the image. The glass is rarely covered in

its entirety by the book and these windows into

the actual room where the scanning is done are

ultimately rendered as solid, censored black. After

the physical scanning process comes post-produc

tion. Software— automated or not— straightens

99

one's files are not always located on one's

equipment. The act of storing and retrieving shuffles

data across machines and state lines.

A public space is produced when something

is shared— which is to say, made public — but this

space is not the same everywhere or in all

circumstances. When music is played for a room full of

people, or rather when all those people are simply

sharing the room, something is being made public.

Capitalism itself is a massive mechanism for

making things public, for appropriating materials,

people, and knowledge and subjecting them to its

logic. On the other hand, a circulating library, or a

library with a reading room, creates a public space

around the availability of books and other forms of

material knowledge. And even books being sold

through shops create a particular kind of public,

which is quite different from the public that is

formed by bootlegging those same books.

ft would appear that publicness is not simply a

question of state control or the absence of money.

Those categorical definitions offer very little to

help think about digital files and their native

tendency to replicate and travel across networks.

What kinds of public spaces are these, coming into

the foreground by an incessant circulation of data?

Tw o paradigmatic forms of publicness can be

described through the lens of the scan and the

export, two methods for producing a digital text.

Although neither method necessarily results in a

file that must be distributed, such files typically

are. In the case of the export, the system of

distribution tends to be through official, secure

digital repositories; limited previews provide a

small window into the content, which is ultimately

accessible only through the interface of the

shopping cart. On the other hand, the scan is

created by and moves between individuals, often

via improvised and itinerant distribution systems.

The scan travels from person to person, like a

virus. As long as it passes between people, that

common space between them stays alive. That

space might be contagious; it might break out into

something quite persuasive, an intimate publicness

becoming more common.

The scan is an image of a thing and is therefore

different from the thing (it is digital, not physical,

and it includes indexes of reading and scanning),

whereas a copy of the export is essentially identical

to the export. Here is one reason there will exist

many variations of a scan for a particular text,

while there will be one approved version (always a

clean one) of the export. A person may hold in his

or her possession a scan of a book but, no matter

what publishers may claim, the scan will never be

the book. Even if one was to inspect two files and

find them to be identical in every observable and

measurable quality, it may be revealed that these

are in fact different after all: one is a legitimate

copy and the other is not. Legitimacy in this case

has nothing whatsoever to do with internal traits,

such as fidelity to the original, but with external

ones, namely, records of economic transactions in

customer databases.

In practical terms, this means that a digital

book must be purchased by every single reader.

Unlike the book, which is commonly purchased,

read, then handed it off to a friend (who then

shares it with another friend and so on until it

comes to rest on someone’

s bookshelf) the digital

book is not transferable, by design and by law.

If ownership is fundamentally the capacity to give

something away, these books are never truly ours.

The intimate, transient publics that emerge out

of passing a book around are here eclipsed by a

singular, more inclusive public in which everyone

relates to his or her individual (identical) file.

Recently, with the popularization of digital

book readers (a device for another man-machine

pairing), the picture of this kind of publicness has

come into greater definition. Although a group of

people might all possess the same file, they will be

viewing that file through their particular readers,

which means surprisingly that they might all be

seeing something different. With variations built

into the device (in resolution, size, colour, display

technology) or afforded to the user (perhaps to

change font size or other flexible design ele

ments), familiar forms of orientation within the

writing disappear as it loses the historical struc

ture of the book and becomes pure, continuous

text. For example, page numbers give way to the

more abstract concept of a "location" when the

file is derived from the export as opposed to the

scan, from the text data as opposed to the

physical object. The act of reading in a group is also

100

different ways. An analogy: they are not prints

from the same negative, but entirely different

photographs of the same subject. Our scans are

variations, perhaps competing (if we scanned the

same pages from the same edition), but, more

likely, functioning in parallel.

Gompletists prefer the export, which has a

number of advantages from their perspective:

the whole book is usually kept intact as one unit,

the file; file sizes are smaller because the files are

based more on the text than an image; the file is

found by searching (the Internet) as opposed to

searching through stacks, bookstores, and attics; it

is at least theoretically possible to have every file.

Each file is complete and the same everywhere,

such that there should be no need for variations.

At present, there are important examples of where

variations do occur, notably efforts to improve

metadata, transcode out of proprietary formats,

and to strip DRM restrictions. One imagines an

imminent future where variations proliferate based

on an additive reading— a reader makes highlights,

notations, and marginal arguments and then

redistributes the file such that someone's

"reading" of a particular text would generate its own public,

the logic of the scan infiltrating the export.

different — "Turn to page 24" is followed by the

sound of a race of collective page flipping, while

"Go to location 2136" leads to finger taps and

caresses on plastic. Factions based on who has the

same edition of a book are now replaced by those

with people who have the same reading device.

If historical structures within the book are

made abstract then so are those organizing

structures outside of the book. In other words, it's not

simply that the book has become the digital book

reader, but that the reader now contains the

library itself! Public libraries are on the brink of be

ing outmoded; books are either not being acquired

or they are moving into deep storage; and physical

spaces are being reclaimed as cafes, restaurants,

auditoriums, and gift shops. Even the concept

of donation is thrown into question: when most

public libraries were being initiated a century ago,

it was often women's clubs that donated their

collections to establish the institution; it is difficult to

imagine a corresponding form of cultural sharing

of texts within the legal framework of the export.

Instead, publishers might enter into a contract

directly with the government to allow access to

files from computers within the premises of the

library building. This fate seems counter-intuitive,

considering the potential for distribution latent

in the underlying technology, but even more so

when compared to the "traveling libraries" at the

turn of the twentieth century, which were literally

small boxes that brought books to places without

libraries (most often, rural communities).

Many scans, in fact, are made from library

books, which are identified through a stamp or a

sticker somewhere. (It is not difficult to see how

the scan is closely related to the photocopy, such

that they are now mutually evolving technolo

gies.) Although it circulates digitally, like the

export, the scan is rooted in the object and is

never complete. In a basic sense, scanning is slow

and time-consuming (photocopies were slow and

expensive), and it requires that choices are made

about what to focus on. A scan of an entire book

is rare— really a labour of love and endurance;

instead, scanners excerpt from books, pulling out

the most interesting, compelling, difficult-to-find,

or useful bits. They skip pages. The scan is partial,

subjective. You and I will scan the same book in

About the Author

Sean Dockray is a Los Angeles-based artist. He is a

co-director of Telic Arts Exchange and has initiated several

collaborative projects including AAAARG.ORG and The

Public School. He recently co-organized There is

nothing less passive than the act of fleeing, a 13-day seminar at

various sites in Berlin organized through The Public School

that discussed the promises, pitfalls, and possibilities for

extra-institutionality.

101

t often the starting-point is an idea composed of

a group of centrally aroused sensations due to simultaneous

excitation of a group

This would probably

in every case he in large part the result of association by

contiguity in terms of the older classification, although

there might be some part played by the immediate

excitation of the separatefP pby an external stimulus. Starting

from this given mass of central elements, all change comes

from the fact that some of the elements disappear and are

replaced by others through a second series of associations

by contiguity. The parts of the original idea which remain

serve as the excitants for the new elements which arise.

The nature of the process is exactly like that by which

the elements of the first idea were excited, and no new

process comes in. These successive associations are thus

really in their mechanism but a series of simultaneous

associations in which the elements that make up the different

ideas are constantly changing, but with some elements

that persist from idea to idea. There is thus a constant

flux of the ideas, but there is always a part of each idea

that persists over into the next and serves to start the

mechanism of revival There is never an entire stoppage

in the course of the ideas, never an absolute break in the

series, but the second idea is joined to the one that precedes

by an identical element in each.

124

A short time later, this control of urban noise had been implemented almost

everywhere, or at least in the politically best-controlled cities, where repetition

is most advanced.

We see noise reappear, however, in exemplary fashion at certain ritualized

moments: in these instances, the horn emerges as a derivative form of violence

masked by festival. All we have to do is observe how noise proliferates in echo

at such times to get a hint of what the epidemic proliferation of the essential

violence can be like. The noise of car horns on New Year's Eve is, to my mind,

for the drivers an unconscious substitute for Carnival, itself a substitute for the

Dionysian festival preceding the sacrifice. A rare moment, when the hierarchies

are masked behind the windshields and a harmless civil war temporarily breaks

out throughout the city.

Temporarily. For silence and the centralized monopoly on the emission,

audition and surveillance of noise are afterward reimposed. This is an essential

control, because if effective it represses the emergence of a new order and a

challenge to repetition.

103

Thus, with the ball, we are all possible victims; we all expose our

selves to this danger and we escape back and forth of "I."

The "I" in the game is a token exchanged. And

this passing, this network of passes, these vicariances of subjects weave

the collection. I am I now, a subject, that is to say, exposed to being

thrown down, exposed to falling, to being placed beneath the compact

mass of the others; then you take the relay, you are substituted for "I"

and become it; later on, it is he who gives it to you, his work done, his

danger finished, his part of the collective constructed. The "we" is made

by the bursts and occultations of the "I." The "we" is made by passing

the "I." By exchanging the "I." And by substitution and vicariance of

the "I."

That immediately appears easy to think about. Everyone carries

his stone, and the wall is built. Everyone carries his "I," and the "we" is

built. This addition is idiotic and resembles a political speech. No.

104

But then let them say it clearly:

The practice of happiness is subversive when it becom es collective.

Our will tor happiness and liberation is their terror, and they react by terrorizing

us with prison, when the repression of work, of the patriarchal family, and of sex

ism is not enough.

But then let them say it clearly:

To conspire means to breathe together.

And that is what we are accused of, they want to prevent us from breathing

because we have refused to breathe In Isolation, in their asphyxiating places of

work, in their individuating familial relationships, in their atomizing houses.

There is a crime I confess I have committed:

It is the attack against the separation of life and desire, against sexism in Interindividual relationships, against the reduction of life to the payment of a salary.

105

Counterpublics

The stronger modification of ... analysis — one in which

he has shown little interest, though it is clearly of major

significance in the critical analysis of gender and sexuality — is that some

publics are defined by their tension with a larger public. Their

participants are marked off from persons or citizens in general.

Discussion within such a public is understood to contravene the rules

obtaining in the world at large, being structured by alternative dis

positions or protocols, making different assumptions about what

can be said or what goes without saying. This kind of public is, in

effect, a counterpublic: it maintains at some level, conscious or

not, an awareness of its subordinate status. The sexual cultures of

gay men or of lesbians would be one kind of example, but so would

camp discourse or the media of women's culture. A counterpublic

in this sense is usually related to a subculture, but there are

important differences between these concepts. A counterpublic, against

the background of the public sphere, enables a horizon of opinion

and exchange] its exchanges remain distinct from authority and

can have a critical relation to power; its extent is in principle

indefinite, because it is not based on a precise demography but

mediated by print, theater, diffuse networks of talk, commerce, and ...

106

The term slang, which is less broad than language variety is described

by ... as a label that is frequently used to denote

certain informal or faddish usages of nearly anyone in the speech community.

However, slang, while subject to rapid change, is widespread and

familiar to a large number of speakers, unlike Polari. The terms jargon

and argot perhaps signify more what Polari stands for. as they are asso

ciated with group membership and are used to serve as affirmation or

solidarity with other members. Both terms refer to "obscure or secret

language’or language of a particular occupational group ...

While jargon tends to refer to an occupational sociolect,

or a vocabulary particular to a field, argot is more concerned with language

varieties where speakers wish to conceal either themselves or aspects of

their communication from non-members. Although argot is perhaps the

most useful term considered so far in relation to Polari. there exists a

more developed theory that concentrates on stigmatised groups, and could

have been created with Polari specifically in mind: anti-language.

For ..., anti-language was to anti-society what language

was to society. An anti-society is a counter-culture, a society within a

society, a conscious alternative to society, existing by resisting either

pas-sively or by more hostile, destructive means. Anti-languages are

generated by anti-societies and in their simplest forms arc partially relexicalised

languages, consisting of the same grammar but a different vocabulary

... in areas central to the activities ot subcultures.

Therefore a subculture based around illegal drug use would have words tor

drugs, the psychological effects of drugs, the police, money and so on. In

anti-languages the social values of words and phrases tend to be more

emphasised than in mainstream languages.

... found that 41 per cent of the criminals he

interviewed cave "the need for secrecy" as an important reason lor using

an anti-language, while 38 per cent listed 'verbal art'. However ...

in his account of the anti-language or grypserka of Polish

prisoners. describes how, for the prisoners, their identity was threatened and

the creation of an anti-society provided a means by wtnclt an alternative

social structure (or reality) could be constructed, becoming the source of

a second identity tor the prisoners.

107

Streetwalker theorists cultivate the ability to sustain and create hangouts by hanging

out. Hangouts are highly fluid, worldly, nonsanctioned,

communicative, occupations of space, contestatory retreats for the

passing on of knowledge, for the tactical-strategic fashioning

of multivocal sense, of enigm atic vocabularies and gestures,

for the development of keen commentaries on structural

pressures and gaps, spaces of complex and open-ended recognition.

Hangouts are spaces that cannot be kept captive by the

private / public split. They are worldly, contestatory concrete

spaces within geographies sieged by and in defiance of logics

and structures of domination.20 The streetwalker theorist

walks in illegitim ate refusal to legitimate oppressive

arrangements and logics.

Common

108

As we apprehend it, the process of instituting com

munism can only take the form of a collection of

acts of communisation, of making common such-and-such

space, such-and-such machine, such-and-such knowledge.

That is to say, the elaboration

of the mode of sharing that attaches to them.

Insurrection itself is just an accelerator, a decisive

moment in the process.

... is a collection of places, infrastructures,

communised means; and the dreams, bodies,

murmurs, thoughts, desires that circulate among those

places, the use of those means, the sharing of those

infrastructures.

The notion of ... responds to the necessity of

a minimal formalisation, which makes us accessible

as well as allows us to remain invisible. It belongs

to the communist way that we explain to ourselves

and formulate the basis of our sharing. So that the

most recent arrival is, at the very least, the equal of

the elder.

Whatever singularity, which wants to appropriate be longing itself,

its own being-in-language, and thus rejects all identity and every

condition of belonging, is the principal enemy of the State. Wherever these

singularities peacefully demonstrate their being in common there will be a

Tiananmen, and, sooner or later, the tanks will appear.