_A talk given at the [Shadow Libraries](http://www.sgt.gr/eng/SPG2096/)

symposium held at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) in

[Athens](/Athens "Athens"), 17 March 2018. Moderated by [Kenneth

Goldsmith](/Kenneth_Goldsmith "Kenneth Goldsmith") (UbuWeb) and bringing

together [Dusan Barok](/Dusan_Barok "Dusan Barok") (Monoskop), [Marcell

Mars](/Marcell_Mars "Marcell Mars") (Public Library), [Peter

Sunde](/Peter_Sunde "Peter Sunde") (The Pirate Bay), [Vicki

Bennett](/Vicki_Bennett "Vicki Bennett") (People Like Us), [Cornelia

Sollfrank](/Cornelia_Sollfrank "Cornelia Sollfrank") (Giving What You Don't

Have), and Prodromos Tsiavos, the event was part of the _[Shadow Libraries:

UbuWeb in Athens](http://www.sgt.gr/eng/SPG2018/) _programme organised by [Ilan

Manouach](/Ilan_Manouach "Ilan Manouach"), Kenneth Goldsmith and the Onassis

Foundation._

This is the first time that I was asked to talk about Monoskop as a _shadow

library_.

What are shadow libraries?

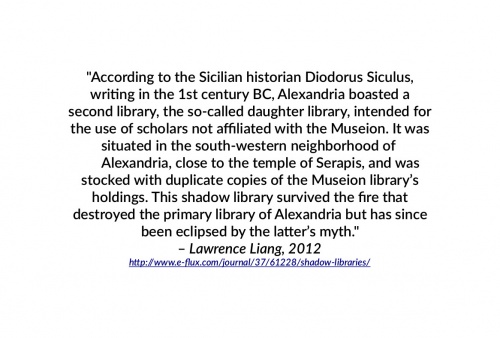

[Lawrence Liang](/Lawrence_Liang "Lawrence Liang") wrote a think piece for _e-

flux_ a couple of years ago,

in response to the closure of Library.nu, a digital library that had operated

from 2004, first as Ebooksclub, later as Gigapedia.

He wrote that:

[](http://www.e-flux.com/journal/37/61228

/shadow-libraries/)

In the essay, he moves between identifying Library.nu as digital Alexandria

and as its shadow.

In this account, even large libraries exist in the shadows cast by their

monumental precedessors.

There’s a lineage, there’s a tradition.

Almost everyone and every institution has a library, small or large.

They’re not necessarily Alexandrias, but they strive to stay relevant.

Take the University of Amsterdam where I now work.

University libraries are large, but they’re hardly _large enough_.

The publishing market is so huge that you simply can’t keep up with all the

niche little disciplines.

So either you have to wait days or weeks for a missing book to be ordered

somewhere.

Or you have some EBSCO ebooks.

And most of the time if you’re searching for a book title in the catalogue,

all you get are its reviews in various journals the library subscribes to.

So my colleagues keep asking me.

Dušan, where do I find this or that book?

You need to scan through dozens of texts, check one page in that book, table

of contents of another book, read what that paper is about.

[](/Digital_libraries#Libraries

"Digital libraries#Libraries")

Or scrapes it from somewhere, since most books today are born digital and live

their digital lives.

...

Digital libraries need to be creative.

They don’t just preserve and circulate books.

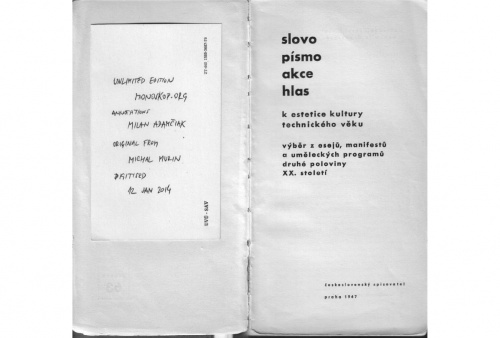

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=10262)

They engage in extending print runs, making new editions, readily

reproducible, unlimited editions.

[](https://monoskop.org/images/d/de/Hirsal_Josef_Groegerova_Bohumila_eds_Slovo_pismo_akce_hlas.pdf#page=87)

This one comes with something extra. Isn’t this beautiful? You can read along

someone else.

In this case we know these annotations come from the Slovak avant-garde visual

poet and composer [Milan Adamciak](/Milan_Adamciak "Milan Adamciak").

[](/Milan_Adamciak

"Milan Adamciak")

...standing in the middle.

A couple of pages later...

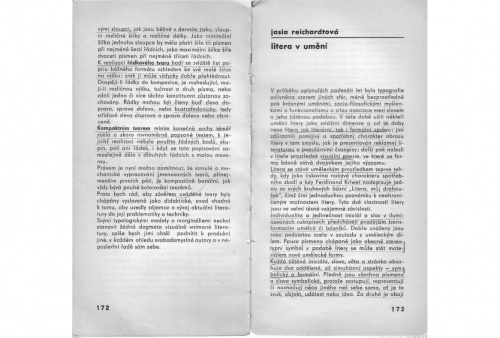

[](https://monoskop.org/images/d/de/Hirsal_Josef_Groegerova_Bohumila_eds_Slovo_pismo_akce_hlas.pdf#page=117)

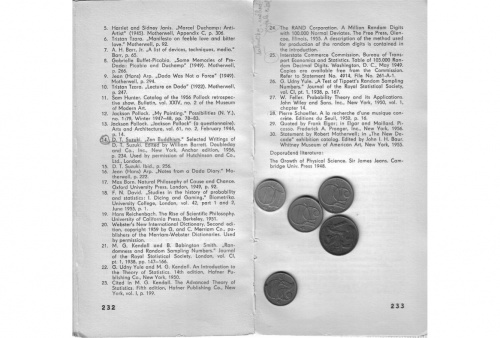

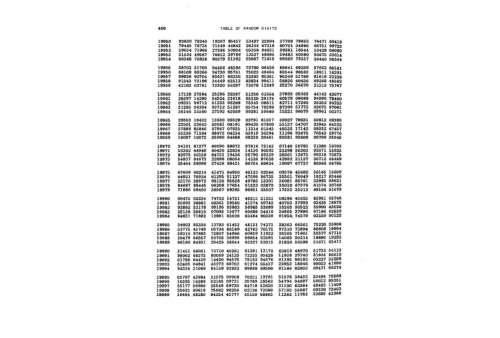

...you can clearly see how he found out about a book containing one million

random digits [see note 24 on the image]. The strangest book.

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=5780)

He was still alive when we put it up on Monoskop, and could experience it.

...

Digital libraries may seem like virtual, grey places, nonplaces.

But these little chance encounters happen all the time there.

There are touches. There are traces. There are many hands involved, visible

hands.

They join writers’ hands and help creating new, unlimited editions.

They may be off Google, but for many, especially younger generation these are

the places to go to learn, to share.

Rather than in a shadow, they are out in the open, in plain sight.

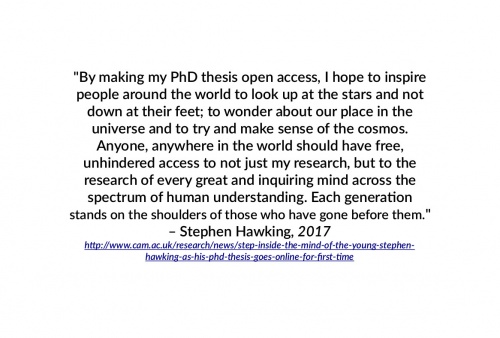

[](http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news

/step-inside-the-mind-of-the-young-stephen-hawking-as-his-phd-thesis-goes-

online-for-first-time)

This made rounds last year.

As scholars, as authors, we have reasons to have our works freely accessible

by everyone.

We do it for feedback, for invites to lecture, for citations.

Sounds great.

So when after long two, three, four, five years I have my manuscript ready,

where will I go?

Will I go to an established publisher or an open access press?

Will I send it to MIT Press or Open Humanities Press?

Traditional publishers have better distribution, and they often have a strong

brand.

It’s often about career moves and bios, plans A’s and plan B’s.

There are no easy answers, but one can always be a little inventive.

In the end, one should not feel guilty for publishing with MIT Press.

But at the same time, one should neither feel guilty for scanning and sharing

such a book with others.

...

You know, there’s fighting, there are court cases.

[Aaaaarg](/Aaaaarg "Aaaaarg"), a digital library run by our dear friend [Sean

Dockray](/Sean_Dockray "Sean Dockray"), is facing a Canadian publisher.

Open Library is now facing the Authors Guild for lending scanned books

deaccessioned from libraries.

They need our help, our support.

But collisions of interests can be productive.

This is what our beloved _Cabinet_ magazine did when they found their PDFs

online.

They converted all their articles into HTML and put them online.

The most beautiful takedown request we have ever received.

[](https://monoskop.org/log/?p=16598)

So what is at stake? What are these digital books?

They are poor versions of print books.

They come with no binding, no paper, no weight.

They come as PDFs, EPUBs, JPEGs in online readers, they come as HTML.

By the way, HTML is great, you can search it, copy, save it, it’s lightweight,

it’s supported by all browsers, footnotes too, you can adapt its layout

easily.

That’s completely fine for a researcher.

As a researcher, you just need source code:

you need plain text, page numbers, images, working footnotes, relevant data

and code.

_Data and code_ as well:

this is where online companions to print books come in,

you want to publish your research material,

your interviews, spreadsheets, software you made.

...

Here we distinguish between researchers and readers.

As _readers_ we will always build our beautiful libraries at home, and

elsewhere,

filled with books and... and external harddrives.

...

There may be _no contradiction_ between the existence of a print book in

stores and the existence of its free digital version.

So what we’ve been asking for is access, basic access. The access to culture

and knowledge for research, educational, noncommercial purposes. A low budget,

poor bandwidth access. Access to badly OCR’d ebooks with grainy images. Access

to culture and knowledge _light_.

Thank you.

Dusan Barok

_Written on 16-17 March 2018 in Athens and Amsterdam. Published online on 21

March 2018._

Dockray

Openings and Closings

2013

Militarization of campuses

Early, on a recent November morning, 400 Military Police with tear gas and helicopters arrested 72 people, almost all students of the University of Sao Paulo. Those people were occupying the Rectory in response to an other arrest – of 3 fellow students – which was itself a consequence of the contract that the university administration signed with the MP, an agreement inviting the police back onto campus after decades in which this presence was essentially prohibited. University “autonomy” had been established by Article 207 of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution to close a chapter on Brazil’s military rule, during which time the Military Police enforced a series of decrees aimed at eliminating opposition to the dictatorship, including the local articulation of the 1960’s student movement. The 1964 Suplicy de Lacerda law forbade student organizations from engaging in politics; in 1968, Institutional Act No. 5 did away with the writ of habeus corpus; and Decree 477 a year later gave university and education authorities the right to expel students and professors involved in protests. A similar provision of “university asylum” restricted the access of policemen onto Greece’s campuses for 35 years. Like Brazil, this measure was adopted after the fall of a military regime that had violently crushed student uprisings and, like Brazil, this prohibition on police incursions into campuses collapsed in 2011. Greek politicians abolished the law in order to more effectively implement austerity measures imposed by European financial interests. Ten days after the raid at the University of Sao Paulo, the chancellor of the University of California, Davis ordered police to clear a handful of tents from a campus quadrangle. Because the peaceful demonstration was planned in solidarity with other actions on UC campuses drawing inspiration from the “occupy movement,” police force swiftly and forcefully dismantled the encampment. Students were pepper-‐sprayed at close range by a well-‐armored policeman wearing little concern. Such examples of the militarization of university campuses have become more common, especially in the context of growing social unrest. In California, they demonstrate the continued influence of Ronald Reagan, not simply for implementing neoliberal policies that have slashed public programs, produced a trillion dollars in US student loan debt and contracted the middle class; but also for campaigning in 1966 for governor of California on a promise to crack down on campus activists, making partnerships with conservative school officials and the FBI in order to “clean out left-‐wing elements” from the University of California. Linda Katehi – that UC Davis chancellor – was also an author of a 2011 report that recommended terminating university asylum to the Greek government. The report noted that “the politicization of students… represents a beyond-‐reasonable involvement in the political process,” continuing on to state that “Greek University campuses are not secure” because of “elements that seek political instability.”

Mobilization of books

After the Military Police operation in Sao Paulo, the rector appeared on television to accuse the students of preparing Molotov cocktails; independent media, on the other hand, described the students carrying left-‐wing books. Even more recently at UC Riverside, a contingent faculty member holding a cardboard shield that was painted to look like the cover of Figures of the Thinkable, by Cornelius Castoriadis, was dragged across the pavement by police and charged with a felony, “assault with a deadly weapon.” In Berkeley, students covered a plaza in books, open and facedown, after their tent occupation was broken up. Many of the crests and seals of universities feature a book, no doubt drawing on the book as both a symbol of knowledge and an actual repository for it. And by extension, books have been mobilized at various moments in recent occupations and protests to make material reference to education and the metastasizing knowledge economy. No doubt the use of radical theory literalizes an attempt to bridge theory and practice, while evoking a utopian imaginary, or simply taking Deleuze’s words at face value: “There is no need to fear or hope, but only to look for new weapons.” Against a background of library closures and cutbacks, as well as the concomitant demands for the humanities and social sciences to justify themselves in economic terms, it is as if books have come into view, desperately, like a rat in daylight. There is almost nowhere for them to go – the space in the remaining libraries is being given over to audio-‐visual material, computer terminals, public programming, and cafes, while publishers are shifting to digital distribution models that are designed to circumvent libraries entirely. So books have come out onto the street. Militarization of Books When knowledge does escape the jurisdiction of both the state and the market, it’s often at the hands of students (both the officially enrolled and the autodidacts). For example, returning to Brazil, the average cost of required reading material for a freshman is more than six months of minimum wage pay, with up to half of the texts not available in Brazil or simply out of print. Unsurprisingly, a system of copy shops provides on-‐demand chapters, course readers, and other texts; but the Brazilian Association of Reprographic Rights has been particularly hostile to the practice. One year before Sao Paulo, at the Federal University in Rio de Janeiro, seven armed police officers in three cars (accompanied by the Chief of the Delegation for the Repression of Immaterial Property Crimes) raided the Xerox room of the School of Social Work, arresting the operator of the machines and confiscating all illegitimate copies. Similar shows of force have proliferated ever since Brazilian copyright law was amended in 1998 to eliminate the exceptions that had previously afforded the right to copy books for educational purposes. This act of reproduction, felt by students and faculty to be inextricably linked to university autonomy and the right to education, coalesced into a movement by 2006, Copiar Livro é Direito! (Copying Books is a Right!) Illicit copies, when confiscated, usually are destroyed. In this sense, it is worthwhile to understand such an event as a contemporary form of censorship, certainly not out of any ideological disapproval of the publication’s actual content, but rather an objection to the manner of its circulation. Many books banned (and burned) during the dictatorship were obviously a matter of content – those that could “destroy society’s moral base” might “put into practice a subversive plan that places national security in danger.” Even if explicit sexuality, crime, and drug use within literature are generally tolerated today (not everywhere, of course) the rhetoric contained within the 1970 decree that instituted censorship is still alive in matters of circulation. During negotiations for the multi-‐national Anti-‐Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), the Bush and Obama administrations denied the public information, stating that it was “properly classified in the interest of national security.” Certain parts of the negotiations became known through Wikileaks and ACTA was revealed as a vehicle for exporting American intellectual property enforcement. Protecting intellectual property is essential, politicians claim, to maintaining the American “way of life,” although today this has less to do with the moral base of the country than the economic base – workers and corporations. America, Obama said in reference to ACTA, would use the “full arsenal of tools available to crack down on practices that blatantly harm our businesses.” Universities, those institutions for the production of knowledge, are deeply embedded in struggles over intellectual property, and moreover deployed as instruments of national security. The National Security Higher Education Advisory Board, which includes (surprise) Linda Katehi, brings together select university presidents and chancellors with the FBI, CIA, and other agencies several times per year. Developed to address intellectual property at the level of cyber-‐theft (preventing sensitive research from falling into the hands of terrorists) the congenial relationship between university administrations and the FBI raises the spectre of US government spying on student activists in the 1960’s and early 1970’s. Financialization of publishing To the side of such partnerships with the state, the forces of financialization have been absorbed into universities, again with the welcome of administrations. Towering US student loan debt is one very clear index; another, less apparent, but growing, is the highly controlled circulation of academic publishing, especially journals and textbooks. Although apparently marginal (or niche) in topic, the vertical structure of the corporations behind most journals is surprisingly large. The Dutch company Elsevier, for example, publishes 250,000 articles per year, and earned $1.6 billion (a profit margin of 36%) in 2010. Texts are written, peer reviewed, and edited on a voluntary basis (usually labor costs are externalized, for example to the state or university). They are sold back to university libraries at extraordinarily high prices, and the libraries are obliged to pay because their constituency relies on access to research as a material for further research. When the website library.nu was taken-‐down recently for providing access to over 400,000 digital texts, it was not the major “commercial” publishers that were behind the action, but a coalition of 17 educational publishers, including Elsevier, Springer, Taylor and Francis, the Cambridge University Press, and Macmillan. On the heels of FBI raids on prominent torrent sites, and with a similar level of coordination, this publishers’ alliance hired private investigators to deploy software “specifically developed by IT experts” to secure evidence. In order to expand their profitability, corporate academic publishers exploit and reinforce entrenched hierarchies within the academia. Compensation comes in the forms of CV lines and disciplinary visibility; and it is that very validation that individuals need to find and secure employment at research institutions. “Publish or die” is not anything new, but as employment grows increasingly temporary and managerial systems for assessment and quantifying productivity proliferate, it has grown more ominous. Beyond intensifying internal hierarchies, this publishing situation has widened the gap between the university and the rest of the world (even as it subjects the exchange of knowledge to the logic of the stock market); publications are meant for current students and faculty only, and their legitimacy is regularly checked against ID cards, passwords, and other credentials. One without such legitimacy finds themselves on the wrong side of a paywall. Here, we discover the quotidian dimension to the militarization of the university, in the inconveniences of proximity cards, accounts, and login screens. If our contemporary forms of censorship are focused on the manner of a thing’s circulation, then systems of control would be oriented towards policing access. Reprographic machines and file-‐sharing software are obvious targets but, with the advent of tablet computers (such as Apple’s iPad, marketed heavily towards students), so are actual textbooks. The practice of reselling textbooks, a yearly student money-‐saving ritual that is perfectly legal under the first-‐sale doctrine, has long represented lost revenue to publishers. So many, including MacMillan and McGraw-‐Hill, have moved strongly into the e-‐textbook market, which allows them to shut the door on the secondary market because students are no longer buying the things themselves, but only temporary access to the things.

Opening of Access

Open Access publishing articulates an alternative, in order to circumvent the entire parasitical apparatus and ultimately deliver texts to readers and researchers for free. In large part, its success depends on whether or not researchers choose to publish their work with OA journals or with pay-‐for-‐access ones. If many have chosen the latter, it is because of factors like reputation and the interrelation between publishing and departmental structures of advancement and power. Interestingly, it is institutions with the strongest reputations that are also pushing for more ‘openness.’ Princeton University formally adopted an open-‐access policy in 2011 (the sixth Ivy League school to do so) in order to discourage the “fruits of [their] scholarship” from languishing “artificially behind a pay wall.” MIT has long promoted openness of its materials, from OpenCourseWare (2002) to its own Open Access policy (2009), to a new online learning infrastructure, MITx. Why is it that elite, private schools are so motivated to open themselves to the world? Would this not dilute their status? The answer is obvious: opening up their research gives their faculty more exposure; it produces a positive image of an institution that is generous and genuinely interested in generating knowledge; and ultimately it builds the university’s brand. They are not giving away degrees and certainly not research positions – rather they are mobilizing their intellectual capital to attract publicity, students, donations, and contracts. We can guess what ‘opening up the university’ means for the institution and the faculty, but what about for the students, including those who may not have the proper title, those learners not enrolled? MITx is an adaptation of the common practice of distance learning, which has a century-‐and-‐a-‐half long history, beginning with the University of London’s External Programme. There are populist overtones (Charles Dickens called the External Programme the “People’s University”) to distance learning that coincide with the promises of public education more generally, namely making higher education available to those traditionally without means for it. History has provided us with less than desirable motivations for distance education – the Free University of Iran was said to have been desirable to the Shah’s regime because the students would never gather – but current western programs are influenced by other concerns. Beyond publicity and social conscience, many of these online learning programs are driven by economics. At the University of California, the Board of Regents launched a pilot program as part of a plan to close a 4.7 billion dollar budget gap, with the projection that such a program could add 25,000 students at 1.1% of the normal cost. Aside from MITx’s free component (it brings in revenue as well if people want to actually get “credit”) most of these distance-‐learning offerings are immaterial commodities. UCLA Extension is developing curricula and courses for Encore Career Institute, a for-‐profit venture bringing together Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and a chairwoman of the UC Regents, whose goal is to “deliver some of the fantastic intellectual property that UC has.” And even MITx is not without its restricted-‐access bedfellows; its pilot online course requires a textbook, which is owned by Elsevier. Students are here conceived of truly as consumers of product, and education has become a subgenre of publication. The classroom and library are seen as inefficient mechanisms for delivering education to the masses or, for that matter, for the delivering the masses to creditors, advertisers, and content providers. Clearly, classrooms will continue to exist, especially in the centers for the reproduction of the elite, such as those proponents of Open Access previously mentioned. But everywhere else, post-‐ classroom (and post-‐library) education is exploding. Students do not gather here and they certainly don’t sit-‐in or take over buildings; they don’t argue outside during a break, over a cigarette, nor do they pass books between themselves. I am not, however, a fatalist on this point – these may be networks of access managed by capital and policed by the state, but new collective forms and subjectivities are already emerging, exploiting or evading the logic of accounts, passwords, and access. They find each other across borders and across disciplines.

Negating Access

After the capitalist restructuring of the 1970s and 1980s, how do we understand the scenes of people clashing with police formations; the revival of campus occupations as a tactic; the disappearance of university autonomy; the withdrawal of learning into the disciplined walls of the academy; in short, how do we understand a situation that appears quite like before? One way – the theme of this essay – would be through the notion of “access.” If access has moved from a question of rights (who has access?) to a matter of legality and economics (what are the terms and price for access, for a particular person?) then over the past few decades we have witnessed access being turned inside-‐out, in a manner reminiscent of Marx’s “double freedom” of the proletariat: having access to academic resources while not being able to access each other. Library cards, passwords, and keys are assigned to individuals; and so are contracts, degrees, loans, and grades. Students (and faculty) are individuated at every turn, perhaps no more clearly than in online learning where each body collapses into their own profile. Access is not so much a passage into a space as it is an apparatus enclosing the individual. (In this sense, Open Access is one configuration of this apparatus). Two projects that I have worked within over the past 7 years – a file-‐sharing website for texts, AAAARG.ORG, and a proposal-‐based learning platform, The Public School – are ongoing efforts in escaping this regime of access in order to create some room to actually understand all of these conditions, their connection to larger processes, and the possibilities for future action. The Public School has no curriculum, no degrees, and nothing to do with the public school system. It is simply a framework within which people propose ideas for things they want to learn about with others; a rotating committee might organize this proposal into an actual class, bringing together a group of strangers and friends who find a way to teach each other. AAAARG.ORG is a collective library comprised of scans, excerpts, and exports that members of its public have found important enough to share with each other. They are premised, in part, on the proposition that making these kinds of spaces is an active, contingent process requiring the coordination, invention, and self-‐ reflection of many people over time. The creation of these kinds of spaces involves a negation of access, often bringing conflict to the surface. What this means is that the spaces are not territories on which pedagogy happens, but rather that the collective activity of making and defending these spaces is pedagogical.

In the militarized raids of campus occupations and knowledge-‐sharing assemblages, the state is acting to both produce and defend a structure that generates wealth from the process of education. While there are occasional clashes over content, usually any content is acceptable that circulates through this structure, and the very failure to circulate (to attract grant funding, attention, or feedback) becomes the operative, soft form of suppression. A resistant pedagogy should look for openings – and if they don’t exist, break them open – where space grows from a refusal of access and circulation, borders and disciplines; from an improvised diffusion that generates its own laws and dynamics. But a cautionary note – any time new social relations are born out of such an opening in space and time, a confrontation with power is not far behind.