»Public Library. Rethinking the Infrastructures of

Knowledge Production«

Exhibition at Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart, 2014

**The present-day social model of authorship is co-substantive with the

normative regime of copyright. Copyright’s avowed role is to triangulate a

balance between the rights of authors, cultural industries, and the public.

Its legal foundation is in the natural right of the author over the products

of intellectual labor. The recurrent claims of the death of the author,

disputing the primacy of the author over the work, have failed to do much to

displace the dominant understanding of the artwork as an extension of the

personality of the author.**

The structuralist criticism positing an impersonal structuring structure

within which the work operates; the hypertexual criticism dissolving

boundaries of work in the arborescent web of referentiality; or the remix

culture’s hypostatisation of the collective and re-appropriative nature of all

creativity – while changing the meaning we ascribe to the works of culture –

have all failed to leave an impact on how the production of works is

normativized and regulated.

And yet the nexus author–work–copyright has transformed in fundamental ways,

however in ways opposite to what these openings in our social epistemology

have suggested. The figure of the creator, with the attendant apotheosis of

individual creativity and originality, is nowadays more forcefully than ever

before being mobilized and animated by the efforts to expand the exclusive

realm of exploitation of the work under copyright. The forcefulness though

speaks of a deep-seated neurosis, intimating that the purported balance might

not be what it is claimed to be by the copyright advocates. Much is revealed

as we descend into the hidden abode of production.

## _Of Copyright and Authorship_

Copyright has principally an economic function: to unambiguously establish

individualized property in the products of intellectual labor. Once the legal

title is unambiguously assigned, there is a property holder with whose consent

the contracting, commodification, and marketing of the work can proceed. In

that aspect, copyright is not very different from the requirement of formal

freedom that is granted to the laborer to contract out their own labor power

as a commodity to capital, allowing then the capital to maximize the

productivity and appropriate the products of the worker’s labor – which is in

terms of Marx »dead labor.« In fact, the analogy between the contracting of

labor force and the contracting of intellectual work does not stop there. They

also share a common history.

The liberalism of rights and the commodification of labor have emerged from

the context of waning absolutism and incipient capitalism in Europe of the

seventeenth and the eighteenth century. Before the publishers and authors

could have their monopoly over the exploitation of their publications

instituted in the form of copyright, they had to obtain a privilege to print a

book from royal censors. First printing privileges granted to publishers, for

instance in early seventeenth century Great Britain, came with the burden

placed on publishers to facilitate censorship and control over the

dissemination of the growing body of printed matter in the aftermath of the

invention of movable type printing.

The evolution of regulatory mechanisms of contemporary copyright from the

context of absolutism and early capitalism receives its full relief if one

considers how peer review emerged as a self-censoring mechanism within the

Royal Academy and the Académie des sciences. [1] The internal peer review

process helped the academies maintain the privilege to print the works of

their members, which was given to them only under the condition that the works

they publish limit themselves to matters of science and make no political

statements that could otherwise sour the benevolence of the monarch. Once they

expanded to print in their almanacs, journals, and books the works of authors

outside of the academy ranks, they both expanded their scientific authority

and their regulating function to the entire nascent field of modern science.

The transition from the privilege tied to the publisher to the privilege tied

to the natural person of the author would unfold only later. In Great Britain

this occurred as the guild of printers, Stationers’ Company, failed to secure

the extension of its printing privilege and thus, in order to continue with

the business of printing books, decided to advocate a copyright for the

authors instead, which resulted in the passing of the Copyright Act of 1709,

also known as the Statute of Anne. Thus the author became the central figure

in the regulation of literary and scientific production. Not only did the

author now receive the exclusive rights to the work, the author was also made

– as Foucault has famously analyzed – the identifiable subject of scrutiny,

censorship, and political sanction by the absolutist state or the church.

And yet, although the romantic author now took center stage, copyright

regulation, the economic compensation for the work, would long remain no more

than an honorary one. Until well into the eighteenth century literary writing

and creativity in general were regarded as resulting from the divine

inspiration and not from the individual genius of the author. Money earned in

the growing business with books mostly stayed in the hands of the publishers,

while the author received an honorarium, a flat sum that served as a »token of

esteem.« [2] It was only with the increasingly vocal demand by the authors to

secure material and political independence from the patronage and authority

that they started to make claims for rightful remuneration.

## _Of Compensation and Exploitation

_

The moment of full-blown affirmation of romantic author-function marks a

historic moment of redistribution and establishment of compromise between the

right of publishers to economic exploitation of the works and the right of

authors to rightful compensation for their works. Economically this was made

possible by the expanding market for printed books in the eighteenth and the

nineteenth century, while politically this was catalyzed by the growing desire

for autonomy of scientific and literary production from the system of feudal

patronage and censorship in gradually liberalizing modern capitalist

societies. The autonomy of production was substantially coupled to the

production for the market. However, the irenic balance could not last

unobstructed. Once the production of culture and science was subsumed under

the exigencies of the market, it had to follow the laws of commodification and

competition that no commodity production can escape.

With the development of big corporation and monopoly capitalism, [3] the

purported balance between the author and the publisher, the innovator or

scientist and the company, the labor and the capital, the public circulation

and the pressures of monetization has become unhinged. While the legislative

expansions of protections, court decisions, and multilateral treaties are

legitimated on basis of the rights of creators, they have become the economic

basis for the monopolies dominating the commanding heights of the global

economy to protect their dominant position in the world market. The levels of

concentration in the industries with large portfolios of various forms of

intellectual property rights is staggering. The film industry is a US$88

billion industry dominated by six major studios. The recorded music industry

is an almost US$20 billion industry dominated by three major labels. The

publishing industry is a US$120 billion industry, where the leading ten earn

in revenues more than the next 40 largest publishing groups. Among patent

holding industries, the situation is a little more diversified, but big patent

portfolios in general dictate the dynamics of market power.

Academic publishing in particular draws a stark relief of the state of play.

It is a US$10 billion industry dominated by five publishers, financed up to

75% from the subscriptions of libraries. It is notorious for achieving extreme

year on year profit margins – in the case of Reed Elsevier regularly well over

20%, with Taylor & Francis, Springer, and Wiley-Blackwell only just lagging

behind. [4] Given that the work of contributing authors is not paid, but

financed by their institutions (provided they are employed at an institution)

and that the publications nowadays come mostly in the form of electronic

articles licensed under subscription for temporary use to libraries and no

longer sold as printed copies, the public interest could be served at a much

lower cost by leaving commercial closed-access publishers out of the equation.

However, given the entrenched position of these publishers and their control

over the moral economy of reputation in academia, the public disservice that

they do cannot be addressed within the historic ambit of copyright. It

requires politicization.

## _Of Law and Politics_

When we look back on the history of copyright, before there was legality there

was legitimacy. In the context of an almost completely naturalized and

harmonized global regulation of copyright the political question of legitimacy

seems to be no longer on the table. An illegal copy is an object of exchange

that unsettles the existing economies of cultural production. And yet,

copyright nowadays marks a production model that serves the power of

appropriation from the author and market power of the publishers much more

than the labor of cultural producers. Hence the illegal copy is again an

object begging the question as to what do we do at a rare juncture when a

historic opening presents itself to reorganize how a good, such as knowledge

and culture, is produced and distributed in a society. We are at such a

juncture, a juncture where the regime regulating legality and illegality might

be opened to the questioning of its legitimacy or illegitimacy.

1. Jump Up For a more detailed account of this development, as well as for the history of printing privilege in Great Britain, see Mario Biagioli: »From Book Censorship to Academic Peer Review,« in: _Emergences:_ _Journal for the Study of Media & Composite Cultures _12, no. 1 [2002], pp. 11–45.

2. Jump Up The transition of authorship from honorific to professional is traced back in Martha Woodmansee: _The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics_. New York 1996.

3. Jump Up When referencing monopoly markets, we do not imply purely monopolistic markets, where one company is the only enterprise selling a product, but rather markets where a small number of companies hold most of the market. In monopolistic competition, oligopolies profit from not competing on prices. Rather »all the main players are large enough to survive a price war, and all it would do is shrink the size of the industry revenue pie that the firms are fighting over. Indeed, the price in an oligopolistic industry will tend to gravitate toward what it would be in a pure monopoly, so the contenders are fighting for slices of the largest possible revenue pie.« Robert W. McChesney: _Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism Is Turning the Internet Against Democracy_. New York 2013, pp. 37f. The immediate effect of monopolistic competition in culture is that the consumption is shaped to conform to the needs of the large enterprise, i.e. to accommodate the economies of scale, narrowing the range of styles, expressions, and artists published and promoted in the public.

4. Jump Up Vincent Larivière, Stefanie Haustein, and Philippe Mongeon: »The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers in the Digital Era,« in: _PLoS ONE_ 10, no. 6 [June 2015]: e0127502, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.

Tomislav Medak is a philosopher with interests in contemporary political

philosophy, media theory and aesthetics. He is coordinating the theory program

and publishing activities of the Multimedia Institute/MAMA (Zagreb/Croatia),

and works in parallel with the Zagreb-based theatre collective BADco.

Barok

Communing Texts

2014

Communing Texts

_A talk given on the second day of the conference_ [Off the

Press](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/22-23-may-2014/program/) _held at

WORM, Rotterdam, on May 23, 2014. Also available

in[PDF](/images/2/28/Barok_2014_Communing_Texts.pdf "Barok 2014 Communing

Texts.pdf")._

I am going to talk about publishing in the humanities, including scanning

culture, and its unrealised potentials online. For this I will treat the

internet not only as a platform for storage and distribution but also as a

medium with its own specific means for reading and writing, and consider the

relevance of plain text and its various rendering formats, such as HTML, XML,

markdown, wikitext and TeX.

One of the main reasons why books today are downloaded and bookmarked but

hardly read is the fact that they may contain something relevant but they

begin at the beginning and end at the end; or at least we are used to treat

them in this way. E-book readers and browsers are equipped with fulltext

search functionality but the search for "how does the internet change the way

we read" doesn't yield anything interesting but the diversion of attention.

Whilst there are dozens of books written on this issue. When being insistent,

one easily ends up with a folder with dozens of other books, stucked with how

to read them. There is a plethora of books online, yet there are indeed mostly

machines reading them.

It is surely tempting to celebrate or to despise the age of artificial

intelligence, flat ontology and narrowing down the differences between humans

and machines, and to write books as if only for machines or return to the

analogue, but we may as well look back and reconsider the beauty of simple

linear reading of the age of print, not for nostalgia but for what we can

learn from it.

This perspective implies treating texts in their context, and particularly in

the way they commute, how they are brought in relations with one another, into

a community, by the mere act of writing, through a technique that have

developed over time into what we have came to call _referencing_. While in the

early days referring to texts was practised simply as verbal description of a

referred writing, over millenia it evolved into a technique with standardised

practices and styles, and accordingly: it gained _precision_. This precision

is however nothing machinic, since referring to particular passages in other

texts instead of texts as wholes is an act of comradeship because it spares

the reader time when locating the passage. It also makes apparent that it is

through contexts that the web of printed books has been woven. But even though

referencing in its precision has been meant to be very concrete, particularly

the advent of the web made apparent that it is instead _virtual_. And for the

reader, laborous to follow. The web has shown and taught us that a reference

from one document to another can be plastic. To follow a reference from a

printed book the reader has to stand up, walk down the street to a library,

pick up the referred volume, flip through its pages until the referred one is

found and then follow the text until the passage most probably implied in the

text is identified, while on the web the reader, _ideally_ , merely moves her

finger a few milimeters. To click or tap; the difference between the long way

and the short way is obviously the hyperlink. Of course, in the absence of the

short way, even scholars are used to follow the reference the long way only as

an exception: there was established an unwritten rule to write for readers who

are familiar with literature in the respective field (what in turn reproduces

disciplinarity of the reader and writer), while in the case of unfamiliarity

with referred passage the reader inducts its content by interpreting its

interpretation of the writer. The beauty of reading across references was

never fully realised. But now our question is, can we be so certain that this

practice is still necessary today?

The web silently brought about a way to _implement_ the plasticity of this

pointing although it has not been realised as the legacy of referencing as we

know it from print. Today, when linking a text and having a particular passage

in mind, and even describing it in detail, the majority of links physically

point merely to the beginning of the text. Hyperlinks are linking documents as

wholes by default and the use of anchors in texts has been hardly thought of

as a _requirement_ to enable precise linking.

If we look at popular online journalism and its use of hyperlinks within the

text body we may claim that rarely someone can afford to read all those linked

articles, not even talking about hundreds of pages long reports and the like

and if something is wrong, it would get corrected via comments anyway. On the

internet, the writer is meant to be in more immediate feedback with the

reader. But not always readers are keen to comment and not always they are

allowed to. We may be easily driven to forget that quoting half of the

sentence is never quoting a full sentence, and if there ought to be the entire

quote, its source text in its whole length would need to be quoted. Think of

the quote _information wants to be free_ , which is rarely quoted with its

wider context taken into account. Even factoids, numbers, can be carbon-quoted

but if taken out of the context their meaning can be shaped significantly. The

reason for aversion to follow a reference may well be that we are usually

pointed to begin reading another text from its beginning.

While this is exactly where the practices of linking as on the web and

referencing as in scholarly work may benefit from one another. The question is

_how_ to bring them closer together.

An approach I am going to propose requires a conceptual leap to something we

have not been taught.

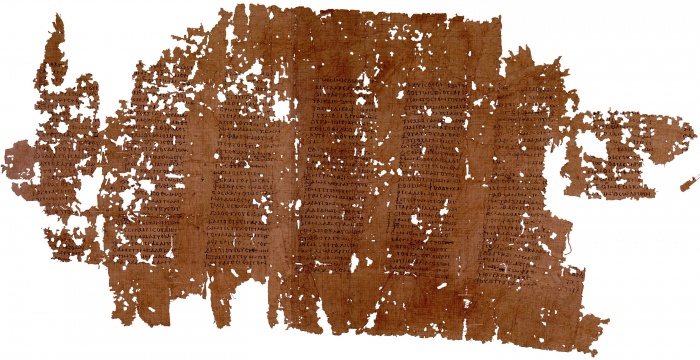

For centuries, the primary format of the text has been the page, a vessel, a

medium, a frame containing text embedded between straight, less or more

explicit, horizontal and vertical borders. Even before the material of the

page such as papyrus and paper appeared, the text was already contained in

lines and columns, a structure which we have learnt to perceive as a grid. The

idea of the grid allows us to view text as being structured in lines and

pages, that are in turn in hand if something is to be referred to. Pages are

counted as the distance from the beginning of the book, and lines as the

distance from the beginning of the page. It is not surprising because it is in

accord with inherent quality of its material medium -- a sheet of paper has a

shape which in turn shapes a body of a text. This tradition goes as far as to

the Ancient times and the bookroll in which we indeed find textual grids.

[](/File:Papyrus_of_Plato_Phaedrus.jpg)

A crucial difference between print and digital is that text files such as HTML

documents nor markdown documents nor database-driven texts did inherit this

quality. Their containers are simply not structured into pages, precisely

because of the nature of their materiality as media. Files are written on

memory drives in scattered chunks, beginning at point A and ending at point B

of a drive, continuing from C until D, and so on. Where does each of these

chunks start is ultimately independent from what it contains.

Forensic archaeologists would confirm that when a portion of a text survives,

in the case of ASCII documents it is not a page here and page there, or the

first half of the book, but textual blocks from completely arbitrary places of

the document.

This may sound unrelated to how we, humans, structure our writing in HTML

documents, emails, Office documents, even computer code, but it is a reminder

that we structure them for habitual (interfaces are rectangular) and cultural

(human-readability) reasons rather then for a technical necessity that would

stem from material properties of the medium. This distinction is apparent for

example in HTML, XML, wikitext and TeX documents with their content being both

stored on the physical drive and treated when rendered for reading interfaces

as single flow of text, and the same goes for other texts when treated with

automatic line-break setting turned off. Because line-breaks and spaces and

everything else is merely a number corresponding to a symbol in character set.

So how to address a section in this kind of document? An option offers itself

-- how computers do, or rather how we made them do it -- as a position of the

beginning of the section in the array, in one long line. It would mean to

treat the text document not in its grid-like format but as line, which merely

adapts to properties of its display when rendered. As it is nicely implied in

the animated logo of this event and as we know it from EPUBs for example.

In the case of 'reference-linking' we can refer to a passage by including the

information about its beginning and length determined by the character

position within the text (in analogy to _pp._ operator used for printed

publications) as well as the text version information (in printed texts served

by edition and date of publication). So what is common in printed text as the

page information is here replaced by the character position range and version.

Such a reference-link is more precise while addressing particular section of a

particular version of a document regardless of how it is rendered on an

interface.

It is a relatively simple idea and its implementation does not be seem to be

very hard, although I wonder why it has not been implemented already. I

discussed it with several people yesterday to find out there were indeed

already attempts in this direction. Adam Hyde pointed me to a proposal for

_fuzzy anchors_ presented on the blog of the Hypothes.is initiative last year,

which in order to overcome the need for versioning employs diff algorithms to

locate the referred section, although it is too complicated to be explained in

this setting.[1] Aaaarg has recently implemented in its PDF reader an option

to generate URLs for a particular point in the scanned document which itself

is a great improvement although it treats texts as images, thus being specific

to a particular scan of a book, and generated links are not public URLs.

Using the character position in references requires an agreement on how to

count. There are at least two options. One is to include all source code in

positioning, which means measuring the distance from the anchor such as the

beginning of the text, the beginning of the chapter, or the beginning of the

paragraph. The second option is to make a distinction between operators and

operands, and count only in operands. Here there are further options where to

make the line between them. We can consider as operands only characters with

phonetic properties -- letters, numbers and symbols, stripping the text from

operators that are there to shape sonic and visual rendering of the text such

as whitespaces, commas, periods, HTML and markdown and other tags so that we

are left with the body of the text to count in. This would mean to render

operators unreferrable and count as in _scriptio continua_.

_Scriptio continua_ is a very old example of the linear onedimensional

treatment of the text. Let's look again at the bookroll with Plato's writing.

Even though it is 'designed' into grids on a closer look it reveals the lack

of any other structural elements -- there are no spaces, commas, periods or

line-breaks, the text is merely one flow, one long line.

_Phaedrus_ was written in the fourth century BC (this copy comes from the

second century AD). Word and paragraph separators were reintroduced much

later, between the second and sixth century AD when rolls were gradually

transcribed into codices that were bound as pages and numbered (a dramatic

change in publishing comparable to digital changes today).[2]

'Reference-linking' has not been prominent in discussions about sharing books

online and I only came to realise its significance during my preparations for

this event. There is a tremendous amount of very old, recent and new texts

online but we haven't done much in opening them up to contextual reading. In

this there are publishers of all 'grounds' together.

We are equipped to treat the internet not only as repository and library but

to take into account its potentials of reading that have been hiding in front

of our very eyes. To expand the notion of hyperlink by taking into account

techniques of referencing and to expand the notion of referencing by realising

its plasticity which has always been imagined as if it is there. To mesh texts

with public URLs to enable entaglement of referencing and hyperlinks. Here,

open access gains its further relevance and importance.

Dušan Barok

_Written May 21-23, 2014, in Vienna and Rotterdam. Revised May 28, 2014._

Notes

1. ↑ Proposals for paragraph-based hyperlinking can be traced back to the work of Douglas Engelbart, and today there is a number of related ideas, some of which were implemented on a small scale: fuzzy anchoring, 1(http://hypothes.is/blog/fuzzy-anchoring/); purple numbers, 2(http://project.cim3.net/wiki/PMWX_White_Paper_2008); robust anchors, 3(http://github.com/hypothesis/h/wiki/robust-anchors); _Emphasis_ , 4(http://open.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/01/11/emphasis-update-and-source); and others 5(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragment_identifier#Proposals). The dependence on structural elements such as paragraphs is one of their shortcoming making them not suitable for texts with longer paragraphs (e.g. Adorno's _Aesthetic Theory_ ), visual poetry or computer code; another is the requirement to store anchors along the text.

2. ↑ Works which happened not to be of interest at the time ceased to be copied and mostly disappeared. On the book roll and its gradual replacement by the codex see William A. Johnson, "The Ancient Book", in _The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology_ , ed. Roger S. Bagnall, Oxford, 2009, pp 256-281, 6(http://google.com/books?id=6GRcLuc124oC&pg=PA256).

Addendum (June 9)

Arie Altena wrote a [report from the

panel](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/off-the-press-report-day-

ii/) published on the website of Digital Publishing Toolkit initiative,

followed by another [summary of the

talk](http://digitalpublishingtoolkit.org/2014/05/dusan-barok-digital-imprint-

the-motion-of-publishing/) by Irina Enache.

The online repository Aaaaarg [has

introduced](http://twitter.com/aaaarg/status/474717492808413184) the

reference-link function in its document viewer, see [an

example](http://aaaaarg.fail/ref/60090008362c07ed5a312cda7d26ecb8#0.102).