UNOVIS

UNOVIS (Utverditeli Novogo Iskusstva [Advocates of New Art], also known as POSNOVIS, Posledovateli Novogo Iskusstva [Followers of the New Art], and MOLPOSNOVIS [Young Followers of New Art]) was a short-lived but influential group of Russian artists, founded and led by Kazimir Malevich at the Vitebsk Art School in 1919.

Contents

In 1919, the MOLPOSNOVIS group was formed by students at the Vitebsk Art School, later joined by some of the school's professors and soon transformed into POSNOVIS. The group was very active, working on numerous projects and experiments, in most if not all media available at the time. In January 1920 Malevich was invited to teach at the school by Chagall and immediately appointed by the director of the school at the time, Vera Ermolaeva, to head a teaching studio. In February 1920, under his leadership, the group worked on a Suprematist ballet, choreographed by Nina Kogan, inspired by Alexei Kruchenykh's influential futurist opera, Victory Over the Sun. Following the production, POSNOVIS underwent more changes and was renamed UNOVIS on 14 February 1920.

In early 1920 Chagall asked Malevich to succeed him as director; Malevich accepted and radically reorganized not only UNOVIS but the entire school's curriculum. UNOVIS was transformed into a highly structured organization, forming the UNOVIS Council. Meanwhile the group's theories and styles were rapidly evolving at the hands of Malevich and his students and colleagues, including notable artists El Lissitzky, Nikolai Suetin, Ilya Chashnik, Vera Ermolaeva, Anna Kagan, and Lev Yudin, amongst others. The group's objective was now to introduce Suprematist designs and ideals to society, working with and for the Soviet government: "organization of design work for new types of useful structures and requirements, and implementation; the formulation of tasks of new architecture; elaboration of new ornamentation (textiles, printed textiles, castings and other products); designs of monumental decorations for use in the embellishment of towns on national holidays; designs for internal and external decoration and painting of accommodation, and implementation; creation of furniture and all objects of practical use; creation of a contemporary type of book and other achievements in the field of printing."

The group took this plan to the streets, furnishing much of Vitebsk in Suprematist art and propaganda. Still, Malevich had more ambitious plans and urged his students to do bigger, more permanent works -- namely architecture. Lissitzky, who was director of the architectural faculty, worked with his student Ilya Chashnik, drafting unorthodox plans for free-floating buildings and enormous steel and glass structures along with more practical designs for housing complexes and even a speaker's podium for the town square. Chashnik would go on to succeed Lissitzky as head of the architectural facility along with his fellow student, Lazar Khidekel.

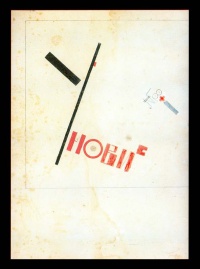

Embracing the Communist ideal, the group chose to share credit and responsibility for all works produced. They signed all works with a solitary black square, a homage to the artwork by Malevich. This would become the de facto seal of UNOVIS and took the place of individual names or initials.

In June 1920 the group's ambitions accelerated, culminating in a print collection of UNOVIS theories and participation in the 'First All-Russian Conference of Teachers and Students of Arts' in Moscow. UNOVIS students travelled there to distribute artworks, newsletters, manifestos, flyers, and copies of Malevich's On New Systems in Art and copies of the UNOVIS Almanac. UNOVIS succeeded in achieving recognition and became respected as an established and influential movement.

In August 1920, UNOVIS included about 40 people: Avidon, I. Baytin, F. Belostotskaya, O. Bernstein, M. Wexler, E. Volkhonsky, I. Gavris, Grigorovich, A. Girutskaya, B. Ermolaeva, L. Zevin, I. Zeldin, AL Zuperman, N. Ivanova, N. Kogan, Korsakov, L. Klyatskin, Kudryashov, M. Kunin, El Lissitzky, E. Magara, K. Malevich, P. Miturich, B. Noskov, GA Noskov, MM Noskov, E. Royak, Rubin, D. Sannikov, Sifman, B. Strzheminsky, N. Suetin Fradkin, L. Khidekel, L. Tsiperson, A. Zeitlin, I. Chashnik, I. Chervinko, L. Yudin.

In April 1922, Malevich with his group (Suetin, Chashnik, Ermolaeva, Hidekilem) moved to Petrograd, where they continued developing ideas of UNOVIS.

In total, UNOVIS as the union was involved in 8 exhibitions: 3 in Vitebsk, 3 in Moscow, First Russian Art Exhibition in Berlin (1922), and The Exhibition of All Areas Over Five Years in St. Petersburg (1923).

While their influence on art lasted for generations, their popularity immediately following the conference was short-lived. By 1922, the core group splintered and two contrasting, adverse factions formed. Malevich and his followers championed practical, productive methods of changing society while the rest favored a more philosophical Suprematism, working on furthering Suprematist theory and ideology. By this time most of the native artists associated with UNOVIS had moved on to other schools, cities, and movements. Even after the group's dissolution, publications bearing the UNOVIS black square appeared for years.

Works

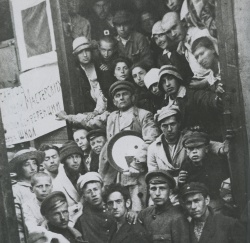

View of UNOVIS exhibition at VKhUTEMAS, Moscow, 1921, showing the works by Kudriashev, Klutsis, and Lissitzky.

View of UNOVIS exhibition at VKhUTEMAS, Moscow, 1921.

Publications

- Almanakh UNOVIS [Альманах Уновис] 1, Vitebsk, 1920, 52 pp, 35.5 х 25.3 cm; facsimile repr., forew. & comm. Tatiana Goriacheva, Moscow: ScanRus [Сканрус], 2003. [4] [5] [6] (Russian)

- UNOVIS. Listok Vitebskogo Tvorkoma, 1 [Уновис. Листок Витебского Творкома № 1], 20 Nov 1920. With texts by Kazimir Malevich, Lazar Khidekel, Ilya Chashnik, and Nina Kogan. (Russian)

Literature

- Aleksandra Shatskikh (Александра Шатских), Vitebsk. Zhizn' iskusstva 1917-1922 [Витебск. Жизнь искусства 1917-1922], Moscow: Yazyki russkoy kultury, 2001, 256 pp. Interview. Review: Zeltser (NK 2002). (Russian)

- Tatiana Goriacheva, "The Almanac Unovis: A Chronicle of Malevich's Vitebsk Experiment", Tretyakov Gallery Magazine 1 (2003), HTML-en, HTML-ru. (English)/(Russian)

- Pamela Kachurin, "The Center of Artistic Life: The People's School of Art in Vitebsk, 1919-1923", ch. 2 in Kachurin, Making Modernism Soviet: The Russian Avant-Garde in the Early Soviet Era, 1918-1928, Northwestern University Press, 2013, pp 37-70. (English)

- Tatyana Goryacheva (Татьяна Горячева), "Almanakh UNOVIS No 1. Vitebsk, 1920" [Альманах УНОВИС № 1. Витебск, 1920], n.d. (Russian)