Difference between revisions of "Alfred Stieglitz"

Sorindanut (talk | contribs) |

Sorindanut (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

* Richard Whelan, ''Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography'', New York: Little, Brown, 1995. | * Richard Whelan, ''Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography'', New York: Little, Brown, 1995. | ||

* Marcia Brennan, ''Painting gender, constructing theory: the Alfred Stieglitz Circle and American formalist aesthetics'', The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2001. | * Marcia Brennan, ''Painting gender, constructing theory: the Alfred Stieglitz Circle and American formalist aesthetics'', The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2001. | ||

| + | * Martin W. Sandler, ''Photography: An Illustrated History'', Oxford University Press, [[ISBN: 0195126084]], 2002. | ||

* Ya'ara Gil Glazer, "A new kind of history? The challenges of contemporary histories of photography", ''Journal of Art Historiography'', no. 3, December 2010 [http://arthistoriography.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/media_183179_en.pdf]. | * Ya'ara Gil Glazer, "A new kind of history? The challenges of contemporary histories of photography", ''Journal of Art Historiography'', no. 3, December 2010 [http://arthistoriography.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/media_183179_en.pdf]. | ||

Revision as of 09:06, 17 December 2013

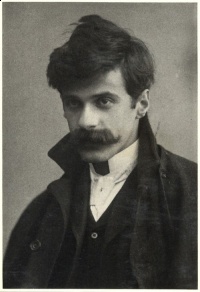

Alfred Stieglitz, self-portrait, ca. 1894 | |

| Born |

January 1, 1864 Hoboken, New Jersey, US |

|---|---|

| Died |

July 12, 1946 (aged 82) New York, US |

Alfred Stieglitz (1864 – 1946) was an American photographer and promoter of photography as art. In early history of photography he represents pictorialist movement. There is no standard definition of the term, but but in general it refers to a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of "creating" an image rather than simply recording it.

Life and work

In 1880s the family moves to Europe and yound Alfred Stieglitz began studying mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin. Here he meets in a chemistry class Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, who was an important scientist and researcher in the then developing field of photography. He bought his first camera and traveled through the European countryside, taking many photographs of landscapes and peasants in Germany, Italy and the Netherlands. In 1884 his parents returned to America, but Stieglitz remained in Germany for the rest of the decade.

During this time Stieglitz began to collect the first books of what would become a very large library on photography and photographers in Europe and the U.S. He read extensively as he collected, and through his library he formulated his initial thinking about aesthetics and photography.

In 1887 he wrote his very first article, "A Word or Two about Amateur Photography in Germany", for the new magazine The Amateur Photographer. Soon he was regularly writing articles on the technical and aesthetic aspects of photography for magazines in England and Germany.

Stieglitz's first photographic recognition was with The Last Joke, Bellagio (1887), photograph who won 1st place in the annual holiday competition held by the British magazine Amateur Photographer.

Several German and British photographic magazines began publishing his work from 1888, when he won both first and second prizes in the same competition. In 1890 after the death of her sister Flora, he returned to New York.

Camera Work (1903-1917)

While magazine Camera Notes set the standard for photographic magazines in the United States, Stieglitz raised the bar even farther with the subsequent journal Camera Work. In 1903 he left the "Camera Club" of New York, established his own group of photographers (the Photo-Secession), and commenced Camera Work, over which he had total control as both editor and publisher. Issued quarterly until the outbreak of World War I, this periodical definitively proved that photography was, indeed, as potent a form of art as painting and sculpture.

Stieglitz achieved this largely through the photogravure plates that graced the 50 issues of Camera Work. He often asked photographers to supply original negatives for plate making and to approve proofs, and he demanded the highest quality from his printers. The gravures usually were printed on delicate Japanese tissue, mounted on textured papers, and individually tipped into the magazines. In each issue, the illustrations were segregated from the magazine's text, creating discrete portfolios of images for quiet contemplation. Stieglitz believed the gravures were equivalents of original photographs, on equal standing with the photographers' platinum or gum-bichromate prints. Prominent pictorialists such as Gertrude Kaesebier, Edward Steichen and Stieglitz himself were well represented in the pages of Camera Work. In 1917, Stieglitz published the last issue, featuring realistic and abstract images by Paul Strand that signaled the dawning of photographic modernism. Today, Camera Work is probably the single best-known example of gravure printing [1].

Gallery

Literature

- Articles and books about Stieglitz

- Newhall Beaumont, The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day, 1939 (1st ed.), New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1982:167-168.

- Richard Whelan, Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography, New York: Little, Brown, 1995.

- Marcia Brennan, Painting gender, constructing theory: the Alfred Stieglitz Circle and American formalist aesthetics, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2001.

- Martin W. Sandler, Photography: An Illustrated History, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 0195126084, 2002.

- Ya'ara Gil Glazer, "A new kind of history? The challenges of contemporary histories of photography", Journal of Art Historiography, no. 3, December 2010 [2].