Difference between revisions of "Media technology in Norway"

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

==Telegraphy, Radio== | ==Telegraphy, Radio== | ||

===Optical telegraph=== | ===Optical telegraph=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Ohlsens_telegraph.jpg|thumb|258px|Ohlsen's telegraph. [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29# | + | [[Image:Ohlsens_telegraph.jpg|thumb|258px|Ohlsen's optical telegraph [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29#23]. Six flaps had three possible positions (up, down, or obscured from view) which allowed 729 combinations, of which only 229 appeared in a [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/optiske/Dag_sign.htm signal book]. A message unit was called ''skrivelse'' [writing], ''rapport'' [report], ''depesje'', and from 1858 ''telegram''. Chappe's telegraph message was called ''dépêche télégraphique'' although Chappe himself preferred ''tachygraph''. [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29#21] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/historie/historie.htm] ]] |

| − | + | Until c1807, there was a flag signaling system in operation in Norway, between the coastal border with Sweden up to Stavanger. | |

| − | In 1802, on the king's request, 'coastal telegrapher' Krigsraad Claus Grooss | + | In 1802, on the king's request, 'coastal telegrapher' Krigsraad Claus Grooss wrote a report in preparation to build the optical telegraph system in Norway. The report considered several options: improvement of the 'vardene' fire system from the Viking times, adoption of the Swedish optical telegraph (developed by [[Abraham Niclas Edelcrantz]] in 1794[http://web.archive.org/web/19981207005630/http://www.it.kth.se/docs/early_net/ch-1-3.html]), and its Danish counterpart ([[Lorenz Fisker]], 1799[http://web.archive.org/web/19990424131240/http://tmpwww.electrum.kth.se/docs/early_net/ch-2-5.1.html]), however none of them were realised due to economical reasons. [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29#21] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/historie/historie.htm] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/signalvesenet.html] |

During the Napoleonic wars, Denmark-Norway and Sweden were neutral up until 1807, when Sweden joint the British, while after the British bombed Copenhagen, Denmark-Norway was forced by Napoleon in February 1808 to declare war on Sweden. | During the Napoleonic wars, Denmark-Norway and Sweden were neutral up until 1807, when Sweden joint the British, while after the British bombed Copenhagen, Denmark-Norway was forced by Napoleon in February 1808 to declare war on Sweden. | ||

| − | Shortly before that, Captain Ole Ohlsen was asked by the upper commander of Norway, prince Christian August, to reorganise the flag system; the result of which was that it took | + | Shortly before that, Captain Ole Ohlsen was asked by the upper commander of Norway, prince Christian August, to reorganise the flag system; the result of which was that it took 75 minutes to deliver a message from Fredriksvern to Christiania (today Oslo), with each station taking 2 minutes to receive and send the signal. [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29#23] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/historie/historie.htm] |

| − | + | ; Ohlsen's telegraph | |

| − | + | In 1808, still unhappy with the result, Ohlsen came up with his own version of Edelcrantz's optical telegraph. A telegraph line was eventually built along the coastal line between Hvaler and Namsos, followed by several mountain lines (the eastern from Hitteroy to Flekkefjord, the western from Stavenger and Bergenhus to Fedje, and the northern lines from Stadlandet to Kristiansund and from Kristiansten to Folda). The network counted 1300 km and 175 stations, built 6-8 km apart (other source claims 227 stations 4-5 km apart [http://web.archive.org/web/19990424131240/http://tmpwww.electrum.kth.se/docs/early_net/ch-2-5.1.html#2-5.1]). The system was used primarily by the Navy. Due to the rough weather conditions and high maintenance costs, the system collapsed after the war, in November 1814. [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29#23] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/historie/historie.htm] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/optiske/opt_tlgr.htm] [http://www.telemuseum.no/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=435&Itemid=102] | |

| − | |||

After 1804, Norway was part of the union with Sweden, where the optical telegraph system opened to civilian use in May 1837 and was used for business, weather forecasting, and search for missing persons. [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29#25] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/historie/historie.htm] | After 1804, Norway was part of the union with Sweden, where the optical telegraph system opened to civilian use in May 1837 and was used for business, weather forecasting, and search for missing persons. [http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/90d74156d548828adc9ef7eb4a1e8d14?index=29#25] [http://www.ludvigsen.hiof.no/webdoc/mastetelegrafen/historie/historie.htm] | ||

Revision as of 18:02, 22 September 2013

Contents

Lithography

After short-lived lithographic practice in Copenhagen and Stockholm, the German portrait painter and draftsman Louis (Friedrich Ludwig) Fehr and his son Gottlieb Louis moved to Oslo in October 1822 and started there the first lithographic printing house in the country. The company produced portraits of famous contemporaries, sheet music, illustrations for scientific publications of the University, administrative business forms (letterheads, invoices, exchange and lending documents), etc. Despite his growing business, Louis Fehr left Norway for Germany in Autumn 1824, and the company was taken over by his other son Carl Louis. [18] [19]

The bookseller Hans Thøger Winther, originally from Denmark (see below), opened his lithographic workshop in Oslo in 1823, and quickly became known for his extensive and varied production. He published portraits of famous Norwegians, landscapes and town prospects and lithographs of the Constitution. His large prospect of Oslo from 1835 provides an excellent view of the city and a number of important buildings. [20] [21]

Georg Prahl (Georg Carl Christian Wedel Prahl) opened a lithographic workshop in Bergen from Autumn 1828. He printed portraits, prospects, sheet music, maps, or a popular school atlas (1836). In connection with lithographs of national and peasant costumes he worked with artists such as Jacob Mathias Calmeyer, Joachim Frich, JFL Dreier and Hans Leganger Reusch. Between 1852–55 he served as chairman of Bergen Art Association [Bergens Kunstforening]. [22] [23]

Among more known painters, Erik Werenskiold, Edvard Munch (from 1894) and Henrik Sørensen worked with lithography. [24]

There are several lithographic workshops operating in Norway today. Grafisk Stentrykk in Oslo was established in 1991 and has two large 'snellpresser' automatic printing machines as well as possibilities for hand press-printing, intaglio printing (photogravure), and die stamping.

Photography

Photographers

- Hans Thøger Winther was born in Thisted in the north of Denmark, and moved to Christiania (today Oslo) in 1801 where he opened a book and music store [Boghandling [25] ] in his house in 1822, lithographic printing house [Steentrykkeri [26] ] in the basement in 1823, rental book library in 1825, book publishing house [Bogtrykkeri [27] ] in 1827, and published several magazines. He was making photographs between 1839 and 1851, as a hobby, never opening a studio. He had heard of Daguerre's discovery in 1839 and without knowing the details experimented with three techniques, direct positive on paper, negative/positive, and diapositive (it is not known that this technique was utilized in photography elsewhere). In 1842 he switched to using paper negatives. Wrote articles on photography as early as October 1839, and the first Norwegian handbook of photography, Anviisning til paa trende forskjellige Veie at frembringe og fastholde Lysbilleder paa Papir, published in 1845. [28] [29] [30]

- O.F. Knudsen was photographing in Christiania in 1840-61. [31]

- Carl Cetti Bendixen from Hamburg worked as daguerreotypist in Bergen in 1843. [32]

- Carl Stelzner, portrait painter and daguerreotypist with a studio in Hamburg, with many Norwegians among his students. He shortly worked in Christiania in August 1843. [33]

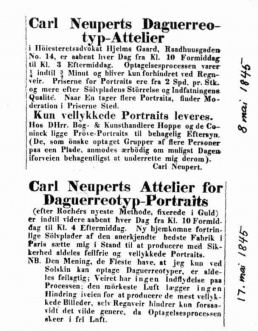

- Carl Neupert, student of Steltzner in Hamburg, ran his studio in Christiania from 15 May 1844 until 1846. He was also active in Kristiansand (1844), Trondheim (1844), Bergen (1844), St. Petersburg (1847), and in Helsinki and other locations in Finland (1848-49). [34] [35] [36]

- Frederik Ulrik Krogh showed a daguerreotype depicting Barrière de la Chapelle in Paris in the Bergen Art Association already in 1840. He worked in Bergen (1844-48) and Stavanger (1844-45). [37]

- Marcus Selmer from Denmark had his studio in Bergen from 1852 until his death in 1900. [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43]

- Knud Knudsen, learnt photography probably from Selmer in Bergen in the late 1850s, and ran his studio there from 1864 to c1915. [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52]

- Anders Beer Wilse created massive photodocumentation of Norway in the first half of the 20th century. [53] [54] [55] [56] [57]

Events

- On 4 February 1839, Den Constitutionelle newspaper reported about Arago's speech in Paris from 7 January.

- October 1840, daguerreotype exhibition in Bergen.

- New Year of 1841, daguerreotype exhibition at Christiania Art Society [Christiania kunstforening], Christiania.

- Norsk fotohistorie – frå daguerreotypi til digitalisering exhibition, Preus museum, 2007. [58]

Resources

- Fotoregistrene [Photo Register], a database of photographers and photo collections/archives in Norway, started in 1992-93, ran by The National Library together with Preus Museum.

- DigitaltMuseum, contains historical photographs fotografier, artifacts, art, altogether more than a million items.

- OsloBilder hosts scans of ten daguerreotypes.

- Other resources.

Preservation

- Fotonettverket [Photography Network], national network for the preservation and dissemination of vernacular photography, includes more than twenty museums, archives and libraries.

Literature

- Ragna Sollied, Eldre bergenske fotografer, Bergen: Eget forlag, 1967. (in Norwegian)

- Ragna Sollied, Eldre norske fotografer, Bergen, 1972. (in Norwegian)

- Susanne Bonge, Eldre norske fotografer. Fotografer og amatørfotografer i Norge frem til 1920, Bergen: Universitetsbiblioteket i Bergen, 1980, 533 pp. (in Norwegian) Contains information about 800 photographers.

- Roger Erlandsen, Vegard S. Halvorsen, Kåre Olsen, Inger Lise Rønning, Norske fotosamlinger 1989-90, Ad Notam Gyldendal, 1989, 232 pp. (in Norwegian)

- Robert Meyer, Den glemte tradisjonen. Oppkomst og utvikling av en nasjonal landskapsfotografi i Norge frem til 1914: en temautstilling fra Robert Meyers fotohistoriske samlinger i anledning av 150-årsjubileet for fotografi, Oslo Kunstforening, 1989, 91 pp. Catalogue. (in Norwegian)

- Oddlaug Reiakvam, Bilderøyndom – Røyndomsbilde: Fotografi som kulturelle tidsuttrykk Oslo: Samlaget, 1997. Dissertation. (in Norwegian)

- Liv Hausken, Om det utidige. Medieanalytiske undersøkelser av fotografi, fortelling og stillbildefilm, Institutt for medievitenskap, Universitetet i Bergen, 1998. Dissertation. (in Norwegian)

- Roger Erlandsen, Pas nu paa! Nu tar jeg fra Hullet! Om fotografiens første hundre år i Norge – 1839-1940, Inter-View & Norges fotografforbund, 2000, 323 pp. (in Norwegian) [59]

- Gunnar Iversen, Yngue Sandhei Jacobsen (eds.), Estetiske teknologier 1700-2000, Scandinavian Academic Press, Oslo, 2003. (in Norwegian) [60]

- Peter Larsen, Sigrid Lien, Norsk fotohistorie. Frå daguerreotypi til digitalisering, Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget, 2007, 344 pp. (in Norwegian) [61], Review, Review.

- Jonas Ekeberg, Harald Østgaard Lund, 80 millioner bilder - Norsk kulturhistorisk fotografi 1855-2005, Forlaget, 2008, 343 pp. (in Norwegian) [62], Review.

- CecilieTyri Holt, Edvard Munchs fotografier, Forlaget, 2013. (in Norwegian)

Telegraphy, Radio

Optical telegraph

Until c1807, there was a flag signaling system in operation in Norway, between the coastal border with Sweden up to Stavanger.

In 1802, on the king's request, 'coastal telegrapher' Krigsraad Claus Grooss wrote a report in preparation to build the optical telegraph system in Norway. The report considered several options: improvement of the 'vardene' fire system from the Viking times, adoption of the Swedish optical telegraph (developed by Abraham Niclas Edelcrantz in 1794[63]), and its Danish counterpart (Lorenz Fisker, 1799[64]), however none of them were realised due to economical reasons. [65] [66] [67]

During the Napoleonic wars, Denmark-Norway and Sweden were neutral up until 1807, when Sweden joint the British, while after the British bombed Copenhagen, Denmark-Norway was forced by Napoleon in February 1808 to declare war on Sweden.

Shortly before that, Captain Ole Ohlsen was asked by the upper commander of Norway, prince Christian August, to reorganise the flag system; the result of which was that it took 75 minutes to deliver a message from Fredriksvern to Christiania (today Oslo), with each station taking 2 minutes to receive and send the signal. [68] [69]

- Ohlsen's telegraph

In 1808, still unhappy with the result, Ohlsen came up with his own version of Edelcrantz's optical telegraph. A telegraph line was eventually built along the coastal line between Hvaler and Namsos, followed by several mountain lines (the eastern from Hitteroy to Flekkefjord, the western from Stavenger and Bergenhus to Fedje, and the northern lines from Stadlandet to Kristiansund and from Kristiansten to Folda). The network counted 1300 km and 175 stations, built 6-8 km apart (other source claims 227 stations 4-5 km apart [70]). The system was used primarily by the Navy. Due to the rough weather conditions and high maintenance costs, the system collapsed after the war, in November 1814. [71] [72] [73] [74]

After 1804, Norway was part of the union with Sweden, where the optical telegraph system opened to civilian use in May 1837 and was used for business, weather forecasting, and search for missing persons. [75] [76]

Electromagnetic telegraph

In 1848, King Oscar I. took a personal initiative in restoring the optical telegraph system on the basis of politically turbulent situation in Europe. Marine lieutenant C.T. Nielsen was sent to study optical telegraphy in Sweden, and he reported that it was replaced by the electric one. [77]

The question was reopened in 1852 since the reports about civilian use of telegraph were coming from abroad. It was turned down by the parliament for financial reasons; the project was finally approved in April 1854. The newly founded Kongelige Elektriske Telegraf quietly opened Norway's first civilian telegraph line between Christiania and Drammen on 1 January 1855. In 1857 the countrywide network was made political priority. The same year Bergen was connected, Trondheim followed in 1858. [78]

In 1861, the 170 km long telegraph line (Lofotlinja) became functional on the Lofoten archipelago. It was a mix of sea cables and land lines, and served nine fishing settlements which were reappearing there during the fishing season (January-March): Skrova, Brettesnes, Svolvær, Ørsvåg (moved to Kabelvåg in 1862), Henningsvær, Steine, Ballstad, Reine and Sørvågen. The line was connected with the rest of the country and Europe in 1867. [79] [80] [81]

By 1870 the whole country was connected.

Telegraph Company which opened in 1855 was among the first to allow women to work (1858), however in the 1880s only 10 percent of all operators were female. In 1920 they achieved the equal pay.

Wireless telegraph

From 1901 military experimented with wireless telegraphy, and in 1902 succeeded in transmitting signal between a ship at Ferder and Horten, 40 km away from each other. During the Union crisis in 1905 the military already had equipment to communicate between ships and the ships and the land. First private ships with radio were Ellis and Preston in 1906, and the next years Marconi and Telefunken companies were selling radio equipment to commercial ships. [82]

Aside from the Navy, developments in wireless telegraphy in Norway were also motivated by the needs of fisheries, the country's major industry ever since the Middle Ages. The ability to send and receive messages about where the fish were and about changes in the weather was invaluable.

In 1902, Hermod Petersen, an engineer from the telecom authorities visited Sørvågen. His investigations concluded that it would be possible to establish a wireless link from Værøy and Røst to Sørvågen, ie. to Lofoten and the rest of the country. The Norwegian parliament (Storting) granted 15,000 kroner to the project. The tests carried out in 1903 exceeded all expectations, and on 1 May 1906, a wireless link was opened between Sørvågen, situated on a tip of the Moskenesøya island, and Røst, on an island over 50 km away, using a Telefunken device. The line became the second radiotelegraph (spark telegraph) for civilian use in the world, after Italy. Petersen wrote an article about the project in the monthly sheet Tekniske Meddelelser fra Telegrafstyrelsen. In 1906, the staff at Sørvågen telegraph station made an unsuccessful effort to establish contact with Emperor Wilhelm II's ship, the "Hohenzollern II". The first successful connection with a ship at sea was eventually established on 1 July 1908. [83] [84] [85] [86] A station in Sørvågen, Moskenes, became the Sørvågen museum in 1914 and later a branch of the Norsk Telemuseum [Norwegian Telecom Museum]). The four telegraph buildings that had been in use from 1861 are still in relatively good condition, as is the 70 metre high radio mast. [87] [88]

Two coastal radios were set up by Navy in Tjøme, Vestfold, and Flekkerøy near Kristiansand, in 1905. They were mostly made to listen to emergency channel for boat traffic and had 100 km range during the day and 400 km at night, having connection with Norwegian boats in Copenhagen, Dutch coast and far out in the North Sea. In 1910 they were taken over by the Telegraph Administration [Statstelegrafen] and used for civilian correspondence as well. [89]

Shortly after, coastal radio (wireless telegraph) stations were built at Finneset (on Spitsbergen, Svalbard, November 1911; from 1925 called Svalbard Radio; moved to Longyearbyen in 1930), Ingøy (north of Hammerfest, 1911), Bergen (September 1912[90]), and elsewhere. [91] [92]

Radio

The state-owned Norwegian Telegraphy Administration [Telegrafvesenet] started working on a radio broadcasting in 1922. After consulting other countries, it recommended that the government own and operate the transmission infrastructure. Norway abolished the ban on listening to foreign radio without a permit in 1923. At the same time a permit became necessary to operate a transmitter. Financing of broadcasting was based on a combination of advertisements, license fees for owning a radio and fee on purchasing a radio. Several companies allied in 1922 for permits to operate radio channels. To avoid similar problems as had occurred in the United States, the administration tried to limited manufacturers of radios from also owning the channels. [93]

Kringkastingsselskapet [The Broadcasting Company] was granted the first permit in 1924. It had more than 2000 shareholders, with major parts owned by Marconi Company, Telefunken and Western Electric. It had a permit to operate a transmitter in Christiania with a reach of 150 kilometers. It was owned by Kringkastingsselskapet, but operated by the Telegraphy Administration. An additional five transmitters were built in Eastern Norway during the 1920s. These included Rjukan in 1925, Notodden and Porsgrunn in 1926 and Hamar and Fredrikstad in 1927. Norway was allocated three AM broadcasting frequencies in 1926. Other radio channels were established in Bergen in 1925, Tromsø in 1926 and Ålesund in 1927. [94]

The company began broadcasting on 29 April 1925 [95]. In 1928 it received permissions to operate in most of the country. In the beginning it was broadcasting a lot of music.

After several scandals, in 1933 Kringkastingsselskapet became part of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation [Norsk Rikskringkasting] (NRK) newly established as a government-owned, national broadcaster, with exclusive right to broadcast voice, music, pictures, etc, in the country. Its first channel, NRK 1, began operating the same year. [96]

Literature

- Det Norske telegrafvesen: 1855-1929, Oslo: Telegrafstyret, 1929.

- Johan Medby, Gjennom splittelse og vanmakt til samling og styrke: det underordnede personale ved Telegrafverket i Oslo: interessestrid og faglig rørsle gjennom 50 år, Oslo, 1950.

- Thorolf Rafto, Telegrafverkets historie 1855–1955, Bergen: John Grieg, 1955, 637 pp. (in Norwegian)

- Anton Blom, Norsk telegraf- og telefonforbund: gjennom 25 år 1930-1955, Oslo: Forbundet, 1955.

- Ole Kallelid, Leif Kjetil Skjæveland, Faget som varte i 100 år: historien til den trådløse telegrafien, Oslo: Norsk telemuseum, 1995, 64 pp.

- Ragnar Østvik, Nasjonen kommer frem over trådene : brytningstid i norsk telefonhistorie 1930-1948, Dragvoll: Senter for teknologi og samfunn, 1997. (in Norwegian)

- Harald Rinde, Tall om tele: introduksjon til telegraf- og telefonstatistikken ca 1855-1993, Sandvika : Handelshøyskolen BI, 1997. (in Norwegian)

- Richard Andersen, Dagfinn Bernstein, Kringkastingens tekniske historie, Oslo: Norsk rikskringkasting, 1999. (in Norwegian)

- Harald Rinde, Norsk telekommunikasjonshistorie: Et telesystem tar form 1855-1920, Oslo: Gyldendal, 2005. (in Norwegian)

- Per H. Lehne, "Enlightening 100 years of telecom history – From ‘Technical Information’ in 1904 to ‘Telektronikk’ in 2004", Telektronikk 100 (3), 2004, pp 3–9.

- Per H. Lehne, "The second wireless in the world", Telektronikk 100 (3), 2004, pp 209–213.

Sound recording

The oldest preserved sound recording made in Norway, 1879.

- A sound recording on tinfoil was made by the music retailer Peder Larsen Dieseth using Edison phonograph on 5 February 1879 at the Tivoli in Oslo. In 1934 Dieseth donated it to the National Museum of Science and Technology, and in 2009 it was digitised by the Research Institute for Industry at the University of Southampton; the recovery process is described here. [97] [98]

- The first gramophone disc in the country was recorded in December 1904 at the Grand Hotel in Oslo. The entertainer Adolf Østbye sang the song Bal i Hallingdal with Carl Mathisen on accordion. The disc is part of the Teknisk Museum's collection. [99] [100] [101]

- Literature

- Ivar Roger Hansen, Per Dahl (eds.), Verneplan for norske lydfestinger, Norsk lydinstitutt, 1997. [102]

- Vidar Vangberg, Norsk lydhistorie, 1879-1935: Historikk og veiledning i innsamling, registrering og anvendelse av historiske lydsamlinger, Oslo: Nasjonalbiblioteket, 1999, 87 pp. (in Norwegian)

- Vidar Vangberg, Da de første norske grammofonstjernene sang seg inn i evigheten: Norsk grammofonhistorie 100 år Oslo: Nasjonalbiblioteket, 2005, 186 pp. (in Norwegian). With a CD containing 25 recordings, mostly from the years 1904-05. [103]

- Hans Fredrik Dahl, Henrik Grue Bastiansen, Norsk mediehistorie, Vol. 2, 2008, 608 pp. (in Norwegian) [104]

- Thomas Bårdsen, Fra evig is til evig tid. Bevaring av 100 år gamle lydopptak, for de neste 1000 år, Nesna, 2010. Master's Thesis. (in Norwegian)