Kazimir Malevich

| |

| Born |

February 23, 1879 near Kiev, Russia (now Ukraine) |

|---|---|

| Died |

May 15, 1935 (aged 56) Leningrad, Soviet Union |

Born 1879 near Kiev to ethnic Poles as the first of 14 children, he is baptised in the Roman Catholic Church. His father manages a sugar factory. Family moves often and he spends most of his childhood in the villages of Ukraine amidst sugar-beet plantations, far from centers of culture. 1895-96 studies drawing in Kiev.

1896-1904 lives in Kursk. 1904 moves to Moscow after the death of his father. 1904-10 studies at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow. 1911 participates in the second exhibition of the group Soyuz Molodyozhi (Union of Youth) in St Petersburg, together with Tatlin; 1912 at the group's third exhibition along the works by Ekster, Tatlin and others. 1912 participates in an exhibition by the collective Donkey's Tail in Moscow. By that time his works were influenced by Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov. 1912 shows the first time outside Russia, at the Blaue Reiter Exhibition. March 1913 a major exhibition of Aristarkh Lentulov's paintings in Moscow, Malevich absorbs the cubist principles. 1913 well-received Cubo-Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun with Malevich's stage-set. 1914 exhibits in the Salon des Independants in Paris with Archipenko, Delaunay, Ekster and Meller, among others.

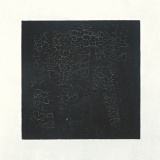

1915 lays down the foundations of Suprematism in manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism. 1915 paints Black Square. 1915–1916 works with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. 1916–1917 participates in exhibitions of the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow together with Altman, Burliuk and Ekster, among others. 1918 paints White on White. 1918 decorates a play, Mystery Bouffe, by Mayakovsky produced by Meyerhold. Interested in aerial photography and aviation, which leads him to abstractions inspired by or derived from aerial landscapes.

1918-19 a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, the Commission for the Protection of Monuments and the Museums Commission. 1919-22 teaches at the Vitebsk Practical Art School where he leads the UNOVIS group; 1922-27 at the Leningrad Academy of Arts; 1927-29 at the Kiev State Art Institute; 1930 at the House of the Arts in Leningrad. 1926 his book The World as Non-Objectivity is published in Munich, only translated into English in 1959; where he outlines his Suprematist theories. 1923 appointed director of Petrograd State Institute of Artistic Culture, which is forced to close in 1926 after a Communist party newspaper called it "a government-supported monastery" rife with "counterrevolutionary sermonizing and artistic debauchery." Summer 1925 meets Eisenstein for the first time, in the village of Nemchinovka, outside Moscow, where Malevich used to spend the summers since the early 1910s. 1925-26 publishes three essays on film in the 'Film Journal ARK', calling for a new language of experimental film to evolve from fine art, as opposed to the traditional sources, photography and theatre. 1927 travels to Warsaw, then to Berlin (29 March-5 June) and Munich for a retrospective which finally brings him international recognition. At his own request, he is introduced by Alexander von Riesen, his escort in Berlin, to Hans Richter. Arranges to leave most of the paintings behind when he returns to the Soviet Union. Stalinist regime turns against forms of abstraction, considering them a type of "bourgeois" art, that could not express social realities; many of his works were confiscated and he is banned from creating and exhibiting similar art. Quietly tolerated by the Communists. Died of cancer in 1935 in Leningrad.

Works

With El Lissitzky, Study for Backcloth for Vitebsk Committee for the Struggle against Unemployment, 1919.

Literature

By Malevich

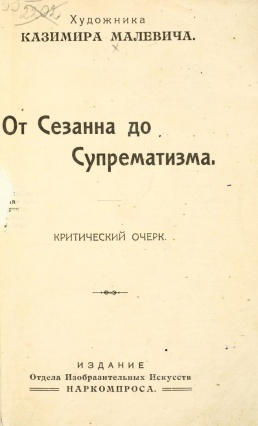

- Ot Sezanna do Suprematizma. Kriticheskiy ocherk [От Сезанна до Супрематизма: Критический очерк], Moscow: Narkompros, 1920, 16 pp. (in Russian) [1]

- Bog ne skinut. Iskusstvo, tserkov’, fabrika, 1922. (in Russian). [2]

- Die gegenstandslose Welt, Bauhausbuch 11, Munich: A. Langen, 1927, 104 pp. (in German). Russian original written in 1923. Excerpt.

- The Non-Objective World, Chicago, 1959.

Articles by Malevich on film

- "On Exposers. Posters" (1925), in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (in Russian/English)

- "I likuyut liki na ekranakh" [И ликуют лики на экранах; And Images Triumph on the Screen], Киножурнал АРК 10 (1925), pp 8-9. (in Russian). Compares Vertov and Eisenstein.

- "And Visages Are Victorious on the Screen", in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (in Russian/English)

- "Khudozhnik i kino" [Художник и кино], Киножурнал АРК 2 (1926). (in Russian)

- "The Artist and the Cinema", in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (in Russian/English)

- "Zhivopis' i problemy arkhitekturnogo priblizheniya novoy klassicheskoy arkhitekturnoy sistemy" [Живопись и проблемы архитектурного приближения новой классической архитектурной системы], 1927, 3 pp. (in Russian). First printed as a facsimile with a French translation in C. Czwiklitzer, Lettres autographes des peintures et sculptures, Basle, 1976, pp 487-488. Russian version repr. as "Художественно-научный фильм Живопись и проблемы архитектурного приближения новой классической архитектурной системы", in Malevich, Классический авангард 3, ed. А.С.Шатских, Vitebsk: Сб; ed. Т.В.Котович. Vitebsk: Областной краеведческий музей, 1999. pp 33-40. A script for an "artistic-scientific film", in manuscript. After seeing Hans Richter's film in Berlin in 1927, Malevich hoped to get assistance from him. The script was lost until the late 1950s. In 1970, Richter began to make an animation based on Malevich's script but the project was left unfinished. [3]

- "Art and the Problems of Architecture. The Emergence of a New Plastic System of Architecture", in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (in Russian/English)

- "[Painting and Photography]. A Letter to Laszlo Moholy-Nagy" (1927), in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (in Russian/English)

- "Kino, grammofon, radio i khudozhestvennaya kul'tura" [Кино, граммофон, радио и художественная культура], early 1928. (in Russian). Manuscript. First printed in Malevich, vol. IV, ed. Troels Andersen, pp 163-176. [4]

- "Cinema, Gramophone, Radio, and Artistic Culture", in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (in Russian/English)

- "Zhivopisnye zakony v problemakh kino" [Живописные законы в проблемах кино], Kino i kul'tura [Кино и культура] 7-8 (1929), pp 22-26. (in Russian)

- "Painterly Laws in the Problems of Cinema", trans. Cathy Young, in Margarita Tupitsyn, Malevich and Film, Yale University Press, 2002, pp 147-159.

- "Pictorial Laws in Cinematic Problems", in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (in Russian/English)

Collected Writings

- Essays on Art 1915-1933, Vol. 1, ed. Troels Andersen, Rapp & Whiting, 1969, 259 pp; New York, 1971.

- The World as Non-Objectivity: Unpublished Writings 1922-25, ed. Troels Andersen, Copenhagen, 1976.

- Essays on Art 1915-1933, Vol. 2, ed. Troels Andersen, Rapp & Whiting, 1978.

- The Artist, Infinity, Suprematism: Unpublished Writings 1913-33, ed. Troels Andersen, trans. Xenia Hoffman, Copenhagen: Borgen, 1978, 260 pp.

- Das weisse Rechteck: Schriften zum Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Berlin: Potemkin Press, 1997, 154 pp. (in German/Russian)

- Черный квадрат [Black Square], 2001. (in Russian)

- Собрание сочинений в пяти томах [Collected Writings in 5 Volumes], Moscow: Gilea. (in Russian)

- Том 1. Статьи, манифесты, теоретические сочинения и другие работы. 1913—1929, 1995. [6]

- Том 2. Статьи и теоретические сочинения, опубликованные в Германии, Польше и на Украине. 1924 - 1930, 1998.

- Том 3. Супрематизм. Мир как беспредметность, или Вечный покой, 2000.

- Том 4. Трактаты и лекции первой половины 1920-х годов. С приложением переписки К.С. Малевича и Эль Лисицкого (1922-1925), 2003.

- Том 5. Произведения разных лет. Статьи. Трактаты. Манифесты и декларации. Проекты. Лекции. Записи и заметки. Поэзия, 2004. [7]

Catalogues

- Suprematism, New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2003.

- Nas budet troe, Moscow: Sepherot Foundation, 2012.

On Malevich

- Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863-1922, Thames and Hudson, 1986.

- Stephen Bann (ed.), The Tradition of Constructivism, Viking Press, 1974.

- John E. Bowlt (ed.), Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902-1934, Viking Press, 1976.

- Margit Rowell, Angelica Zander Rudenstine, Art of the Avant-Garde in Russia: Selections from the George Costakis Collection, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1981.

- Margarita Tupitsyn, Malevich and Film, Yale University Press, 2002, 192 pp. With essays by Kazimir Malevich and Victor Tupitsyn. Contents, [8]

- Kent Mitchell Minturn, "Seeing Malevich, Cinematically", Art Journal 63:4 (Winter 2004), pp 141-144. A review of Bulgakowa's and Tupitsyn's books.

- Charlotte Douglas, Christina Lodder (eds.), Rethinking Malevich: Proceedings of a Conference in Celebration of the 125th Anniversary of Kazimir Malevich’s Birth, London: Pindar Press, 2007, 381 pp.

- Constructivism in Europe: From Malevich to Kandinsky, Beijing: Art Museum of China, 2012.

See also

External links

- http://www.kazmalevich.info (Russian)

- Biography and works

- Suprematist works by Malevich

- Video

- "Malevich’s Burial Site Is Found, Underneath Housing Development", August 2013.

- The Malevich Archive in the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

- Malevich at Wikipedia

- http://users.i.com.ua/~lak/russian/film-malevich.htm