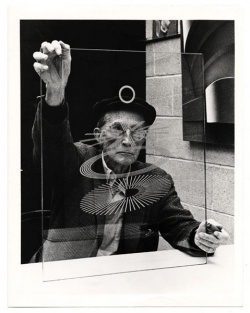

Marcel Duchamp

c1960. | |

| Born |

May 28, 1887 Blainville, France |

|---|---|

| Died |

October 2, 1968 (aged 81) Neilly-sur-Seine, France |

| Web | Aaaaarg, Wikipedia, Using "Academia.edu" as base chain is not permitted during the annotation process., Open Library |

Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) was a painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Dadaism, avant-garde and conceptual art.

In 1904, he joined his artist brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, in Paris, where he studied painting at the Académie Julian until 1905. Duchamp’s early works were Post-Impressionist in style. He exhibited for the first time in 1909 at the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne in Paris. His paintings of 1911 were directly related to Cubism but emphasized successive images of a single body in motion. In 1912, he painted the definitive version of Nude Descending a Staircase; this was shown at the Salon de la Section d’Or of that same year and subsequently created great controversy at the Armory Show in New York in 1913.

Duchamp’s radical and iconoclastic ideas predated the founding of the Dada movement in Zurich in 1916. By 1913, he had abandoned traditional painting and drawing for various experimental forms, including mechanical drawings, studies, and notations that would be incorporated in a major work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23; also known as The Large Glass). In 1914, Duchamp introduced his readymades—common objects, sometimes altered, presented as works of art—which had a revolutionary impact upon many painters and sculptors. In 1915, Duchamp traveled to New York, where his circle included Katherine Dreier and Man Ray, with whom he founded the Société Anonyme in 1920, as well as Louise and Walter Arensberg, Francis Picabia, and other avant-garde figures.

After playing chess avidly for nine months in Buenos Aires, Duchamp returned to France in the summer of 1919 and associated with the Dada group in Paris. In New York in 1920, he made his first motor-driven constructions and invented Rrose Sélavy, his feminine alter ego. Duchamp moved back to Paris in 1923 and seemed to have abandoned art for chess but in fact continued his artistic experiments. From the mid-1930s, he collaborated with the Surrealists and participated in their exhibitions. Duchamp settled permanently in New York in 1942 and became a United States citizen in 1955. During the 1940s, he associated and exhibited with the Surrealist émigrés in New York, and in 1946 began Etant donnés: 1. la chute d’eau 2. le gaz d’éclairage, a major assemblage on which he worked secretly for the next 20 years. [1]

Publications

- with Beatrice Wood and Henri-Pierre Roché, The Blind Man, 2 issues, New York: Henri Pierre Roché, 1917. Magazine. (English)

- with Beatrice Wood and Henri-Pierre Roché, Rongwrong, New York, 1917, JPGs. Magazine. (French)

- with Man Ray, New York Dada, 1921. One-issue magazine. (English)

- as Rrose Sélavy, Some French Moderns Says McBride, New York: Société Anonyme, 1922, 18 sheets. A collection of essays by the art editor and critic Henry McBride, published in the New York Sun and the New York Herald, 1915-1922, compiled and designed by Duchamp. (English)

- with Katherine S. Dreier and Man Ray (as Société Anonyme), International Exhibition of Modern Art, New York: Société Anonyme and Museum of Modern Art, 1926, 124 pages. Catalogue. (English)

- A L'Infinitif, New York: Cordier & Ekstrom, 1966, 32 pp. Manuscript notes from 1912-20. (English)

- Notes and Projects for the Large Glass, ed. Arturo Schwarz, New York: H.N. Abrams, 1969. (English)

Catalogues, writings and interviews

- Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Marcel Duchamp, New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1957. Catalogue. (English)

- Marchand du sel: Écrits de Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michel Sanouillet, Paris: Terrain vague, 1959; new ed., corr. & augm., as Duchamp du signe: Écrits, ed. Michel Sanouillet with Elmer Peterson, Paris: Flammarion, 1976, 314 pp; 1994. (French)/(English)

- Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, eds. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, New York: Oxford University Press, 1973; UK ed. as The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp, London: Thames and Hudson, 1975, 195 pp. (English)

- Escritos. Duchamp du Signe, trans. Josep Elias and Carlota Hesse, Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1978, 254 pp. (Spanish)

- Die Schriften, Bd. 1: Zu Lebzeiten veröffentlichte Texte, trans. & ed. Serge Stauffer, Zurich: Regenboden, 1981. (German)

- Interview with James Johnson Sweeney, in Wisdom: Conversations with the Elder Wise Men of Our Day, ed. James Nelson, New York: W.W. Norton, 1958, pp 89-99. Conducted late 1955 in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (English)

- Pierre Cabanne, Etretiens avec Marcel Duchamp, Paris: Pierre Belfond, 1967; Allia, 2014, 160 pp. (French) [2]

- Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett, London: Thames and Hudson, 1971; Da Capo Press, 1987, 136 pp. (English)

- The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Arturo Schwarz, New York: H.N. Abrams, 1969; 3rd ed., New York: Delano Greenidge, 1997, 750 pp. (English)

- Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life, ed. & intro. Pontus Hulten, MIT Press, 1993, 650 pp. Texts by Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont; with 1,200 illustrations; published as the catalogue to the Palazzo Grassi (Venice) exhibition in June 1993. (English)

- with Calvin Tomkins, The Afternoon Interviews, Badlands Unlimited/National Philistine, 2013, 110 pp. Conducted 1964 in New York. (English)

- Bibliography

- Timothy Shipe, "Marcel Duchamp: A Selective Bibliography", Dada/Surrealism 16 (1987), pp 231-265; upd. in The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, 3rd ed., ed. Arturo Schwarz, New York, 1997; upd., with Kathryn M. Floyd, in Etant donné Marcel Duchamp 5ff (2003). (English)

Literature

- Calvin Tomkins, "Marcel Duchamp", in The Bride and the Bachelors: Five Masters of the Avant-Garde, Viking, 1965; new ed., exp., new intro., Viking, 1968; Penguin, 1976, 306 pp, Log. (English)

- Calvin Tomkins, The World of Marcel Duchamp, 1887–1968, New York: Time-Life Books, 1966; rev.ed., 1972, Log. Draws on interviews and materials gathered for Tomkins’ 1965 profile of Duchamp in The New Yorker. (English)

- Jean-François Lyotard, Les transformateurs Duchamp, Paris: Galilée, 1977. (French)

- Duchamp’s TRANS/formers, trans. Ian McLeod, Venice, CA: Lapis Press, 1990, 208 pp, Log. (English)

- Thierry De Duve (ed.), The Definitely Unfinished Marcel Duchamp, MIT Press, 1991, 550 pp.

- October 70: "The Duchamp Effect", MIT Press, Fall 1994, 146 pp, ARG. (English)

- Dalia Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit, University of California Press, 1995, HTML. (English)

- Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996; 2014. PDF (pp 1-43). (English)

- Thierry de Duve, Kant after Duchamp, MIT Press, 1996, PDF. (English)

- Jerrold Seigel, The Private Worlds of Marcel Duchamp: Desire, Liberation, and the Self in Modern Culture, University of California Press, 1997, HTML.

- Jindřich Chalupecký, Úděl umělce. Duchampovské meditace, afterw. Pavla Pečinková, Prague: Torst, 1998, 456 pp, Log. (Czech)

- Alice Goldfarb Marquis, Marcel Duchamp: The Bachelor Stripped Bare, Boston: MFA Publications, 2002, 368 pp, Log. (English)

- John F. Moffitt, Alchemist of the Avante-Garde: The Case of Marcel Duchamp, SUNY Press, 2003, 468 pp, Log. (English)

- Herbert Molderings, John Brogden, Duchamp and the Aesthetics of Chance: Art as Experiment, Columbia University Press, 2010, PDF.

- Cahiers Philosophiques 131: "Marcel Duchamp" (2012). (French) [3] [4]

- 3 New York Dadas and the Blind Man: Marcel Duchamp, Henri-Pierre Roché, Beatrice Wood, London: Atlas, 2014. [5] (English)

Documentary

- Marcel Duchamp: Iconoclaste et Inoxydable, dir. Fabrice Maze, 2009.