Dziga Vertov

| |

| Born |

January 2, 1896 Białystok, Russian Empire (now Poland) |

|---|---|

| Died |

February 12, 1954 (aged 58) Moscow, Soviet Union (now Russia) |

| Web | UbuWeb Sound, Wikipedia |

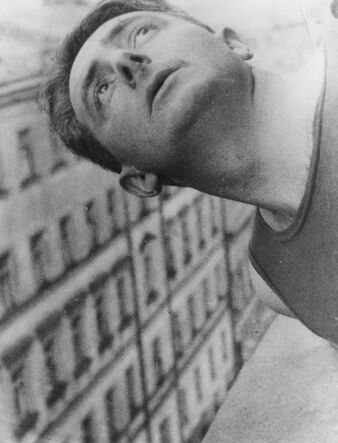

David Abelevich Kaufman (Давид Абелевич Кауфман; Denis Kaufman; pseudonym Dziga Vertov; Дзига Вертов) was a director, screenwriter, and theoretician of documentary film, one of the creators of its language. He came to Soviet documentary film in 1918, inspired by the ideas of the revolution, and became known as a vivid innovator and experimenter. Vertov’s films One Sixth of the World (1926), Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1930), Three Songs about Lenin (1934), and especially Man with a Movie Camera (1929) remain models for generations of documentary filmmakers.[1]

His filming practices and theories influenced the cinéma vérité style of documentary moviemaking and the Dziga Vertov Group, a radical filmmaking cooperative which was active in the 1960s.

Vertov's brothers Boris Kaufman and Mikhail Kaufman were also noted filmmakers, as was his second wife, Elizaveta Svilova.

Contents

- 1 Early years

- 2 Early film work

- 3 Kino-Pravda (1922–25)

- 4 Stride, Soviet! and One Sixth of the World (1926)

- 5 Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- 6 Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1930)

- 7 Three Songs about Lenin (1934)

- 8 Later years

- 9 Family

- 10 Reception and legacy

- 11 Archives and Collections

- 12 Filmography

- 13 Sound recordings

- 14 Bibliography

- 15 Notes

- 16 See also

- 17 Links

Early years[edit]

| A biography of Vertov presented here borrows from what appears to be the most informed English-language account of Vertov's life to this day, the film and Slavic literature scholar John MacKay's 2012 essay, "Dziga Vertov (1896-1954)"[2]. One of his numerous essays on Vertov informed by his archival research in Russia, Ukraine and Poland, it is to be followed by a book-length study[3]. Some visual material and English translations of Vertov's quotes are sourced from Andrey Smirnov's groundbreaking book on early sound experiments and electronic music in Russia, Sound in Z[4]. Additional sources were consulted. |

Białystok[edit]

Vertov was born David Abelevich (later changed to Denis Arkadievich) Kaufman into a Jewish book-dealer’s family in Białystok, Russian Empire (now Poland).

He was a pupil at the Białystok Modern School [realnoe uchilishche] from August 1905 through June 1914[5], and (from c1912) studied violin, piano and music theory at the city's conservatory as well.[6][7]

Petrograd[edit]

Starting in the fall of 1914, Vertov began a general course of study at psychologist Vladimir Bekhterev's famous Psychoneurological Institute in Petrograd[8] — the only Russian institution prior to the February Revolution (of 1917) that was accepting Jewish students.[9] His classmates counted the future globetrotting Soviet journalist Mikhail Koltsov (his former classmate from Białystok as well), future journalist Larissa Reisner, future film historian and filmmaker Grigorii Boltianskii, and future director Abram Room. Meanwhile, with the advance of German troops into Białystok in August 1915, Vertov's family became refugees in Petrograd and later Moscow. Vertov was recruited into a special musical section at a military academy in Chuguev, near Khar’kov, Ukraine – early in the fall of 1916, and never returned to his studies in the Psychoneurological Institute, although he may have intended to. He remained at the academy until the February Revolution of 1917, after which time he left for Moscow, the city that was to be his base for the remainder of his days.[10]

He took his pseudonym at around 1918. “Vertov” is a futurist neologism derived from the Russian verb vertit’sia, to spin or turn; “Dziga” is the Ukrainian word for a “(spinning) top”, although he has been signing his poems in that fashion since at least 1915. As an adult, he was formally addressed as "Denis Arkadievich Vertov", and this sort of Russification of name was typical for the young members of the Russophilic Jewish milieu in which he grew up.[11]

Experiments with sound[edit]

Impressed and influenced, like many others of his generation, by futurism, he began to write science fiction and sound poems, experimenting with the perception and arrangement of sound. During the summer 1916 vacation he began his first experiments with sound, producing verbal montage structures.[12]

In 1916 he attempted what would now be called sound poetry and audio art. As he put it: "I had an idea about the need to enlarge our ability for organized hearing. Not limiting this ability to the boundaries of usual music. I decided to include the entire audible world into the concept of 'Hearing'."[13] He attempted to create new forms of organization of sound by means of a rhythmic grouping of phonetic units. During his schooling Vertov struggled with text. Once, preparing for classes, he discovered that after organizing geographical place names in a rhythmic order, he could easily remember the entire sequence. This became his favourite method of memorizing.[14]

"As a result of these self-enforced experiments I became interested in the rhythmic organization of separate elements of the visible and audible world in general. The next stage was my passion for editing shorthand records. It concerned not only the formal connection of these pieces but also the interaction of meanings of separate pieces of shorthand records. It also concerned my experiments with gramophone recordings, where from the separate fragments of recordings on gramophone discs a new composition was created. But I was not satisfied experimenting with available pre-recorded sounds. In nature I heard considerably more different sounds, not just singing or a violin from the usual repertoire of gramophone discs."[15][16]

"On vacation, near Lake Ilmen. There was a lumber-mill which belonged to a landowner called Slavjaninov. At this lumber-mill I arranged a rendezvous with my girlfriend... I had to wait hours for her. These hours were devoted to listening to the lumber-mill. I tried to describe the audio impression of the lumber-mill in the way a blind person would perceive it. In the beginning I wrote down words, but then I attempted to write down all of these noises with letters.

Firstly, the weakness of this system was that the existing alphabet was not sufficient to be able to write down all of the sounds that you hear in a lumber-mill. Secondly, except for sounding vowels and consonants, different melodies, motifs, could still be heard. They needed to be written down as musical signs. But corresponding musical signs did not exist. I came to the conviction that by existing means I could only achieve onomatopoeia, but I couldn’t really analyze the heard factory or a waterfall... The inconvenience was in the absence of a device by means of which I could record and analyze these sounds. Therefore I temporarily left aside these attempts and switched back to work on the organization of words.

Working on the organization of words, I managed to destroy that contrast which in our understanding and perception exists between prose and poetry... Some of these works, which seemed to me more or less accessible to a wide audience, I tried to read aloud. More complex works, which required a long and careful reading, I wrote down on big yellow posters. I hung out these posters in the city. I attached them myself.

My work and the room where I worked were called the ‘Laboratory of Hearing’."[17]

Early film work[edit]

After the 1917 February Revolution Vertov was for several months studying law at Moscow University, also attending lectures in the Department of Mathematics.[18]

Kino-Nedelya (1918–19)[edit]

Koltsov, who became acquainted with the Bolshevik intellectuals Anatoly Lunacharsky and Grigorii Chicherin shortly after the October 1917 events, and was named chair of the newsreel division of the All-Russian Cinema Committee of the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment early in 1918, hired Vertov as his secretary in May of that year.[19] Although Vertov, unlike Koltsov, never joined the Bolshevik Party – indicating instead in a 1918 questionnaire that his political sympathies were “anarchist-individualist” in character – he became committed early on to the Soviet cause, as both an administrator and a filmmaker.[20]

Vertov, being frustrated by the absence of any adequate means for sound recording, switched to film. As he reflected: "Once in the spring of 1918... returning from a train station there lingered in my ears the signs and rumble of the departing train ... someone swearing ... a kiss ... someone’s exclamation ... laughter, a whistle, voices, the ringing of the station’s bell, the puffing of the locomotive ... whispers, cries, farewells ... And I thought to myself whilst walking: I must get a piece of equipment that won’t describe but will record, photograph these sounds. Otherwise it’s impossible to organize, to edit them. They rush past, like time. The movie camera perhaps? Record the visible ... Organize not the audible, but the visible world. Perhaps that’s the way out?"[21][22]

By the end of 1918, Vertov had taken over administrative responsibility for the first Soviet newsreel series, Kino-Nedelya [Кино-Неделя; Cinema Week] (43 issues between May 1918 and June 1919); in 1920 and 1921, he took part as administrator, programmer and film presenter on the "October Revolution" agitational train, one of a number of such trains that went through territories recently captured by the Red Army during the civil war, propagandizing for the new regime, and often carrying various high-level representatives of that regime onboard. (It was in connection with his work on this train that he met his first wife, pianist and fellow activist Olga Toom.) During this period, he made the acquaintance of many figures who would play important roles in Soviet fiction and non-fiction film, including actor and director Vladimir Gardin, director and pedagogue Lev Kuleshov, and cameramen Eduard Tisse and Aleksandr Levitskii. By 1922 he was one of those in charge of newsreel production at Moscow’s film studio, and remained at the center of non-fiction film work there until 1927.[23]

Vertov worked on the Kino-Nedelya series for three years, helping establish and run a film-car on Mikhail Kalinin's agit-train during the ongoing Russian Civil War between Communists and counterrevolutionaries. Some of the cars on the agit-trains were equipped with actors for live performances or printing presses; Vertov's had equipment to shoot, develop, edit, and project film. The trains went to battlefronts on agitation-propaganda missions intended primarily to bolster the morale of the troops; they were also intended to stir up revolutionary fervor of the masses.

Further newsreels[edit]

In 1919, Vertov compiled newsreel footage for his full-length documentary Anniversary of the Revolution; in 1921 he compiled History of the Civil War. He followed it with two short films, Battle of Tsaritsyn (1920, now lost), about a Civil War battle, the first film on which Vertov worked with the woman who would be his second wife and main lifelong collaborator, veteran film editor Elizaveta Svilova[24], and The Agit-Train VTSIK (1921) from touring together with President Kalinin the battlefronts of southwest Russia on a propaganda train known as The October Revolution. In 1922, he made the thirteen-reel History of Civil War (1922).[25][26]

Kino-Pravda (1922–25)[edit]

Although the initial idea for a major Soviet newsreel combining information and agitation came from director Fyodor Otsep of the non-state-owned “Rus’” firm, the Commissariat of Enlightenment (Narkompros) decided to entrust the task to Vertov’s documentary group, who were soon to become known as the kinoks (from the Russian kino [cinema] and oko [eye]). At the centre of that group were Svilova and cameramen Ivan Belyakov and Mikhail Kaufman; the latter had been demobilised in 1922, after having served as a driver and mechanic in the Red Army during the civil war, and was to be Vertov's close collaborator for the next seven years.[27]

Kino-Pravda [Cine-Truth] (23 issues between May 1922 and March 1925) was named in honor of Pravda, the Soviet daily newspaper founded by Lenin. Issued irregularly, it offered reportage on an extremely wide variety of subjects and acted as a laboratory for the development of a film vocabulary (particularly from the thirteenth issue onward). During this period, Vertov developed his montage techniques and honed his growing theories about cinema as the art form best suited for the masses. The evolution of the series was characterised both by the deployment of an increasingly rich repertoire of devices--including archival footage, news footage, animations, experiments with moving intertitles, reenactments, and (contrary to Vertov's stated principles) staged sequences--and by increasing structural and thematic unity; the series culminated in inventive treatments of single themes like the Young Pioneer organisation, the death of Lenin, or the visit of a peasant to the city. The fourteenth Kino-Pravda (late 1922) includes mobile constructivist intertitles designed by Rodchenko. With the production of Kino-Pravda no. 6, Kaufman became Vertov's principal cameraman. [28][29][30]

The use of the candid camera was adopted by the kinoks (the Council of Three and followers) in 1923 or 1924, possibly in large part as a result of Mikhail Kaufman's filming experience, since Vertov was primarily an editor, not a cameraman. In 1926 Mikhail Kaufman made the documentary film Moscow, whose structure, relating a day in the life of a great industrial city, seems to have influenced both Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) and Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera (1929).[31]

Kinoks' LEF manifesto[edit]

In December 1922, the group ("Council of Three") issued an appeal to Soviet filmmakers, published under the title "Kinoks: A Revolution (Appeal for a Beginning)" in the June 1923 issue of the magazine LEF, in which they derided all fiction films as backward, packed with lies and powerless while lauding those films that recorded the truth of real life ‘caught unawares’.[32][33]

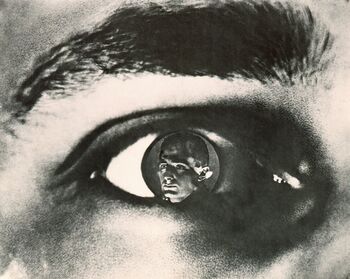

Kino-Eye (1924)[edit]

The culmination of the Kino-Pravda period is the feature-length film Kino-Eye: Life Caught Unawares [Kinoglaz: Zhizn’ vrasplokh] (1924), which comprises five autonomously structured reels joined only by the overriding theme of the activities of the Young Pioneer troops from Moscow’s “Red Defense” factory and from the village of Pavlovskoe, located near the capital. 1924 and Kino-Eye also saw the culmination of Vertov’s efforts to establish kinok groups throughout the USSR, mainly via the networks established by the still somewhat inchoate Pioneer organization.[34]

Stride, Soviet! and One Sixth of the World (1926)[edit]

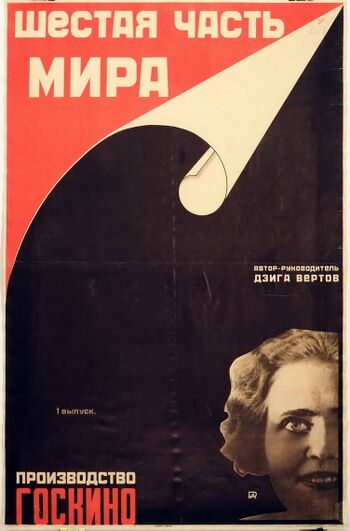

Vertov’s success with the Lenin memorial film Kino-Pravda 21 led to two major commissions: Stride, Soviet! (Shagai, Sovet!, 1926), an election-year promotional film for the Moscow City Soviet, and the grandiose One Sixth of the World (Shestaia Chast’ Mira, 1926), a film commissioned by the state trade organization Gostorg to promote Soviet exports abroad. Both films became occasions for remarkable experiments in structure, audience address, and intertitle construction, and aroused considerable interest, controversy and, from some of those who commissioned the films, ire.[35]

In particular, One Sixth of the World’s combination of savage anti-capitalist satire, ethnographic cataloguing, and ambiguous economic argumentation, all articulated across an arc of Walt Whitman-inflected poetic intertitles, proved difficult to assimilate, and the film was never, in fact, used for promotional purposes. Vertov was fired at the beginning of January 1927 from Moscow’s Sovkino studio, following the release of the film, after a series of ferocious arguments with studio head Ilya Trainin. The disputes initially centered on what was thought to be the excessive cost of the One Sixth production and on Trainin’s decision to pass directorial control over a planned found-footage film commemorating the tenth anniversary of the Revolution to Esfir Shub, reached the boiling point when Vertov, advocate of the non-scripted film, refused to present Trainin with a script for Man with a Movie Camera, footage for the never-realised first version of which Vertov had been amassing through 1925-26.[36]

After several months of melancholy unemployment (during which time he wrote a script for a never-to-be-produced film on Jewish agricultural settlement in the Crimea), Vertov was hired by VUFKU (the All-Ukrainian Photo-Film Directorate, based in Kyiv and at this time staffed with artists and administrators sympathetic to Ukrainian futurism), under whose auspices he made three masterpieces in quick succession.[37][38]

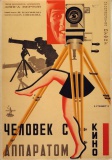

Man with a Movie Camera (1929)[edit]

|

Vertov was first contracted by VUFKU to make a film about industrialization in the Ukrainian SSR, with a focus on the construction of the Dnepr Hydroelectric Station. This film was released in 1928 as The Eleventh Year [Odinnadtsatyi]. Soon afterwards, he resumed work on his pet project, Man with a Movie Camera [Chelovek s kinoapparatom] (1929). This work, shown in Germany, France, England and the United States after its initial release, fell into almost total obscurity for the next thirty years. Now widely regarded as the most formally inventive and intellectually complex film of the silent era, Man with a Movie Camera has become a touchstone for discussions of documentary, experimental practice in film, and cinematic self-reflexivity. The film was also, however, his last collaboration with Mikhail Kaufman: relations between the brothers had become strained during the production of The Eleventh Year, and they were on non-speaking terms until 1933.[39]

This section is to be expanded.

Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1930)[edit]

Vertov’s final Ukrainian--and first sound--film, Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass [Entuziazm: Simfoniia Donbassa] (1930), shot in the heat of the First Five-Year Plan in the mines and factories of Eastern Ukraine, is both one of his most politically problematic works – the film was shot during the beginning stages of agricultural collectivization, though not during the most violent and destructive phases of that campaign – and one of his most artistically innovative, especially as regards its unprecedented and still astonishing use of documentary sound.[40]

First Five-Year Plan[edit]

The film at once depicts, celebrates, participates in and was shaped by the First Five-Year Plan for economic development (1928-1932), the Stalin regime’s ambitious industrialization campaign. The Donbass area of eastern Ukraine, rich in coal and iron deposits, in which Vertov, Svilova and their team of kinoks filmed and recorded most of Enthusiasm, was one of the main “fronts” of the Plan.[41]

The trope of the Donbass as absolute center seems to derive from a passage in a speech Lenin gave at the 11th Congress of the Russian CP in March 1922, a passage quoted verbatim on Vertov’s “idea chart”: “[The Donbass] is the center, the real basis of our entire economy. There can be no question of any renewal of heavy industry in Russia, no question of any real construction of socialism (for there is no way to build it except through heavy industry), if we do not revive the Donbass and bring it back up to the mark”[42] Securing the Donbass had been one of Lenin’s major strategic concerns during the Civil War.[43]

Collectivisation[edit]

The kinoks shot without sound in the Donbass from September to November 1929, continued in Leningrad during four days in January 1930 at St. Isaac’s Cathedral, at a sound movie theater and other locales around the city, while at the same time engaging in an intensive study of sound technology. After a crash course in the inventor Alexander Shorin’s system of sound recording (involving experiments conducted both at the professor’s laboratory and open-air), the group shot documentary sounds and images in and around Leningrad until May 1930. They were in Kharkov for the Eleventh Ukrainian Party Congress (5-15 June 1930), and soon after that went to the Donbass, where they remained until around the end of July.[44]

Collectivisation—that is, the forced conversion of villages into collective farms and the requisitioning of peasant property—began in deadly earnest in Ukraine in November 1929, while the kinoks were still in the Donbass hundreds of violent clashes occurred all over rural Ukraine between November 1929 and March 1930. (The horrors of collectivization culminated in the famine of 1932-33, in which nearly seven million people died, mostly in Ukraine.)[45]

In a diary entry from 1934/5, Vertov mourned that he "made [a] mistake when [he] gave in, submitted to management’s demands and began to edit Enthusiasm even though [he] knew full well that all the human documents [zasniatyi chelovecheskii material] were ruined due to technical reasons." [46]

Structure[edit]

The film begins with an overture on the “clearing of social space” (through the abolition of the twin “opiates” of religion and alcohol) as precondition for socialist construction (reels 1 and 2); moving to the long middle section on the industrialization of the Donbass region of Ukraine (reels 3 through 5); and a last movement (reel 6) where the products of industrialization flow back to the USSR (most notably to the countryside) and are celebrated.[47][48]

Musique concrète[edit]

The portable sound-on-film equipment specially built by Alexander Shorin allowed kinoks to record actual urban sounds: industrial noises in the harbour, sounds of the railroad and the railway station, streets and trams, utilized in the film.[52]

Vertov considered this film a Symphony of Noises and it is structured as a programmatic four-movement symphony in which leitmotivs and refrains develop a musical narration. Vertov was uninterested in using imitative instruments to recreate sounds and was irritated by such imitations in early sound films[53]; instead the kinoks developed the techniques based on montage and relying on varying the speed of recorded sounds in post-production. They could edit the soundtrack by cutting sounds, putting them in loops and combining them according to principles of musical composition. For this, in late November 1929 together with the composer Nikolai Timofeev Vertov developed a musical score that integrated noises and their transformation, distortion and variation, forerunning the aesthetics of musique concrète by nearly two decades[54]. Nevertheless, following political problems, he never returned to it.[55]

The shooting was not without obstacles. The sound equipment, in addition to the other gear, had to be pulled around most of the time by hand. At the film’s first preview on 1 November 1930 in Kiev, Vertov said that the recording apparatus, which he had at his disposal for 1 month and 10 days in the Donbass, weighed 78 poods (approximately 2,808 pounds), that they had no transportation for it, and that 80 percent of the group’s work consisted in “sheer physical labor.”[56]

Biomechanics[edit]

The film contains a unique documentary about the training of Aleksei Gastev’s CIT cadets, biomechanical ballet, recalling performances in Solomon Nikritin’s Projectionist Theatre.[57]

Reception[edit]

After its first public screenings in Europe in 1931 the film achieved significant success. In a note sent to Vertov from London, Charlie Chaplin wrote: "Never had I known that these mechanical sounds could be arranged to sound so beautiful. I regard it as one of the most exhilarating symphonies I have heard. Mr. Dziga Vertov is a musician. Professors should study with him and not argue."[58][59]

In Germany, after initially generating intense interest, the film was banned by the government in October 1931 (while Vertov was touring Europe), a prohibition that elicited protest from Joris Ivens, Hans Richter, Béla Balázs, and Lászlo Moholy-Nagy, among others.[60][61]

The Moscow screenings for political representatives were met with hostile reception.[62] In a more relaxed atmosphere in Kiev, Vertov responded to the criticism of the sound layer:

"Now, concerning the noises themselves: I declare categorically that there’s not one noise in the film. This notion of “noise” is deployed simply in order to scare workers in sound film away from the sounds that exist in nature. These existent [...] sounds are called “noises” only in order to distinguish them from so called music; that is, from those various “do, re, mi, fa”’s and the like, which we can handle very well and can distinguish wonderfully from one another—while at the same time [being] unable to distinguish one natural sound from another (for example the sound of a steam engine, the sound of a threshing-machine, a steamship piston, and so on) in all of its nuances. Yes, for a domestic lapdog, obviously, all sounds are the same—but we’re not domestic lapdogs, we’re not delicate, Western, flowery directors; we do not make, as Eisenstein does, gypsy romances; and for us, there are no noises. We must acknowledge that we began [in cinema] like literary people, that we’re not sufficiently literate in existing sounds and don’t distinguish among them. If [...] you go to the Donbass, then all you’ll hear [at first] is one uninterrupted roar and noise—that’s the first impression. But this wasn’t my first time in the Donbass;[63] I studied these sounds and saw that, yes, we really are domestic, and for us these sounds are “noise”—but for the worker in the Donbass every sound has a specific meaning; for him there are no “noises.” And if it seems to you, comrades, who know all the scales perfectly, that I am at this moment emitting pure noise, then I can assure you that I am [producing] no noise whatsoever."[64]

Three Songs about Lenin (1934)[edit]

By June 1932 Vertov was working at the Mezhrabpomfil’m studio, and spent most of the next year and a half working on what was to be his greatest popular success, Three Songs about Lenin [Tri pesni o Lenine] (1934). A tribute to Lenin that integrates many of the tropes and even some of the footage from Vertov’s 1920s films with “folk” music and poetry and innovative sync sound interviews, Three Songs about Lenin turned out to be the last film over which Vertov had relatively complete artistic control. The highly selective deployment of "folk" motifs from the Muslim regions of the USSR, together with his innovative sync sound interviews with workers, produced at once Vertov's most powerful representations of the coordination of national-ethnic and Soviet identities, and his most successful attempt to accommodate his experimental formal preoccupations with the new stress on narrative clarity and exemplary subjects typical of emergent socialist realism. He was awarded the Order of the Red Star in 1935, and had the opportunity to re-release the film in 1938, after adding a section of a speech by Stalin to the conclusion, and removing images of political luminaries who had in the interim become “enemies of the people” (Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev or Radek). Unlike Mikhail Koltsov, Vertov and Svilova escaped the Terror of 1937-38 physically unscathed; they even received a modest new apartment at the end of 1938, but no other “perks” were coming their way, as it turned out. It seems that Vertov's loss of the patronage of Koltsov (and no doubt others) during the Terror, his inability to sustain a working collective, his often vocal obstinacy, and his gradually declining health all contributed to the waning of his productivity from 1938 onward.[65]

Later years[edit]

For Lullaby [Kolybel’naia] (1937), he wrote a script attacking the historical exploitation (particularly the sexual exploitation) of women, but his conception was altered almost beyond recognition during the course of production. In the end, Lullaby, which also enjoyed a U.S. release but played only a few days on Soviet screens, ended up being less about women than about children and the “paternal care” offered to all Soviet citizens by the state, as personified by Stalin and given codified form in the 1936 constitution.[66]

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, in the wake of Lullaby, Vertov and Svilova ended up wandering from one studio to another, working on films that either went unreleased (Three Heroines [Tri geroini], 1938, about the famous women pilots Raskova, Osipenko, and Grizodubova), or unproduced altogether (The Girl and the Giant [Devochka i velikan], on which he conceived in 1940-41 with famous children’s author M. Il’in). Vertov's health had begun to fail from the mid-1930s, and while in Alma-Ata during World War II (where he made a remarkable film about Kazakh war production entitled To You, Front [Tebe, Front], 1942), he suffered a nervous breakdown.[67]

During the war, the Nazis murdered Vertov’s father, mother and all his close relatives from Bialystok and the surrounding area sometime between 1941 and 1943. Along with Mikhail and Boris, Vertov attempted to uncover the details about his family’s fate, but to no avail.[68]

Svilova was responsible for editing the very first film about Auschwitz [Osventsim] (1945), and worked with Roman Karmen on a major documentary about the Nuremberg Trials (Judgement of the Peoples [Sud narodov], 1946), which won a Stalin Prize; she herself had received this prize for her work with Yuli Raizman on Berlin (1945), which also garnered the best short film award at the 1946 Cannes Film Festival.[69]

Vertov’s last noteworthy film, The Oath of Youth [Kliatva Molodykh], about the commitment of Komsomol members to the war effort, was roundly criticised by studio supervisors in August 1944 and not accepted for wide release. In the months that followed, until the end of 1944, Vertov desperately proposed at least five different script ideas in rapid succession, but like virtually all the proposals he had offered since 1938, they went unproduced and unnoticed. After this point – that is, from 1944 until 1954, when he died - Vertov stopped presenting ideas for films, or new ideas about film, instead managing to find occasional work on non-descript News of the Day newsreels.[70]

Dziga Vertov died of stomach cancer in Moscow in 1954.

Family[edit]

Around the time when working on Anniversary of the Revolution (summer 1918), Vertov married the pianist Olga Toom (Ольга Тоом). She was briefly acquainted with the major Bolshevik activist Nadezhda Krupskaya (Lenin's wife), and Maria Uljanova (Мария Ульянова), worked in their secretariats, in the agit-trains and in the newspaper Pravda, accompanying them on numerous trips. They split in the early 1920. Vertov wrote a short poem on the occasion: "Hands require / a single loop to / connect us to the aspen autumn" [Руки требуют / Чтобы в единой петле / Соединила нас на осине осень]. [4] [5] [6]

Several years later, Vertov married his long-time collaborator Elizaveta Svilova.

Vertov's brother Mikhail Kaufman (1897-1980) was Vertov’s main cameraman and close collaborator between 1922 and 1929, and later became an important documentary director in his own right. His other brother, Boris (1903-1980), never practiced filmmaking in Russia, and began to work as a cameraman and sometime co-director in France in the mid-1920s, eventually doing the cinematography for the early films of Jean Lods, all the films of Jean Vigo, and, still later in the US, for films like Sidney Lumet’s Twelve Angry Men (1957) and Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954), for which he won an Academy Award.[71]

Reception and legacy[edit]

1928-35 marked the apex of Vertov’s worldwide fame and influence, and during those years, articles about his work were published everywhere from the US and Argentina to Czechoslovakia and Japan. He took two trips to Europe – from the beginning of May through the beginning of August 1929, and from July 1931 to the beginning of 1932 – during which time he showed his films in Germany, France, the Netherlands, and England, and met Germaine Dulac, Léon Moussinac, and Joris Ivens among others. Both trips were primarily lecture tours accompanied by film screenings.[72] For example, in June 1929 he presented his paper "What is Cinema-Eye" in Hanover, Berlin, Dessau, Essen and Stuttgart. [7]

Svilova, who retired immediately after Vertov’s death, dedicated the rest of her life to promoting his memory. Kopalin, too -- by now teaching in the documentary section of the state film school and one of the grand old men of Soviet nonfiction film -- began writing and publishing about Vertov’s films as early as June 1955. Articles about and references to Vertov and his films started to appear with some regularity in the pages of official Soviet film publications from 1956 onwards, and serious scholarship on Vertov (carried out by Nikolai Abramov, Sergei Drobashenko, Viktor Listov, Lev Roshal’, and others) was well underway in the USSR by the mid-1960s.[73]

Abroad, full retrospectives were staged as early as 1960 in Leipzig, followed by important screenings in Paris, Venice, and Vienna. The Western memory of Vertov was sustained by some of those who had known his work (Joris Ivens, Hans Richter, Leon Moussinac) and some who had not, like Georges Sadoul, whose posthumous book on Vertov (1971) appeared around the same time as Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s experimental Groupe Dziga Vertov collective, and preceded the major essays and books by Annette Michelson, Seth Feldman, Vlada Petrić, and (later) Yuri Tsivian, Thomas Tode, Aleksandr Deriabin, Emma Widdis, Oleg Aronson, Elizabeth Papazian and John MacKay among others. Although the late 1980s and 1990s saw the beginnings of a reconsideration of Vertov in light of his propaganda work on behalf of Soviet power, his reputation has been complicated rather than undermined by new research, including recent assimilations of Vertov to media studies (Lev Manovich[74], the Vienna-based "Digital Formalism" project).[75]

Archives and Collections[edit]

- The Russian State Archive of Literature and Art has Vertov's writings and pictures donated by Svilova.

- Vertov's collection at Svenska Filminstitutet, pursued by Anna-Lena Wibom, contains mainly photocopies of texts, but also frame enlargements and photos.

- The Dziga Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum includes film scripts, records, writings, photographs and collected news coverage originally collected by Svilova. Background.

Filmography[edit]

- Kino-nedelya [Кинонеделя; Cinema Week], 43 installments, 1919. [8] [9] [10]. Weekly newsreels. Produced by the Film Committee of the People's Commissariat of Public Education (Moscow). 1 June 1918 through 24 December 1919. Written and directed by Vertov.[76]

- Godovshchina revolyutsii [Годовщина революции; The Anniversary of the Revolution], 12 reels, 1919. [11]. Historical chronicle. Produced by the Film Committee of the People's Commissariat of Public Education (Moscow). Directed by Vertov.[77]

- Boy pod Tsaritsynym [Битва в Царицыне; The Battle of Tsaritsyn], 3 reels, 1919. Produced by the Revolutionary Military Council and the Film Committee of the People's Commissariat of Public Education (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov.[78]

- Protsess Mironova [Процесс Миронова; The Trial of Mironov; The Mironov Case], 1 reel, 1919. Produced by the Revolutionary Military Council and the Film Committee of the People's Commissariat of Public Education (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov.[79]

- Vskrytie moshchey Sergiya Radonezhskogo [The Disinterment of Serge Radoneski], 2 reels, 1921. Film-reportage. Produced by the Film Committee of the People's Commissariat of Public Education (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov.[80]

- Agitpoezd VTsIK [Агитпоезд ВТсИК; The Propaganda Train of the Russian Central Executive Committee], 1 reel, 1921. Travelogue. Produced by the Russian Central Executive Committee and the Film Committee of the People's Commissariat of Public Education (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov.[81]

- Istoriya grazhdanskoy voyny [История гражданской войны; A History of the Civil War], 13 reels, 1922. Historical chronicle. Produced by the Photo-Film Division (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov.[82]

- Protsess eserov [Процесс эсеров; The Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries; Trial of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party], 3 reels, 1922. Produced by the Photo-Film Division (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov.[83]

- Kinokalendar (State Film-Calendar), 55 issues, 1923-25. Daily and weekly (flash) newsreels. Produced by Goskino (Kultkino). 21 July 1923 through 5 May 1925. Written and directed by Vertov. Includes "Lenin Film-Calendar".[84]

- Kino-Pravda [Кино-Правда], 23 issues (30-37, 40, 43), 1922-25. [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20]. Film-newspaper. Produced by Goskino (Moscow). 5 June 1922 through 1925. Shooting plan, intertitles, and direction by Vertov. All installments of the Kino-pravda appeared under this title, with the exception of the eight issues: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow (13), 1923; Autumn Pravda (16), 1923; Black Sea--Sea of Ice--Moscow (19), 1924; Pioneers' Pravda (20), 1925; Leninist Kinopravda (21), 1924; Lenin Lives in the Peasant's Heart (22), 1925; Radio-Kinopravda (23), 1925; Give Us Air (Special issue), 1924.[85]

- Sovietskie igrushki [Советские игрушки; Soviet Toys], 1924.

- Kino-Glaz: zhizn' vrasplokh [Кино-глаз: Жизнь врасплох; Kino-Eye: Life Caught Unawares / Kino-Eye: Life Unrehearsed], first series, 6 reels, 1924. [21] [22]. Produced by Goskino (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov. Cameraman: Mikhail Kaufman.[86]

- Shagay, sovet! [Шагай, Совет!; Stride Soviet (The Moscow Soviet: Past, Present, and Future], 6 reels, 1926. [23] [24] Newsreels. Produced by Goskino (Kultkino) (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov. Cameraman: I. Belyakov. Film scout: Kopalin. Assistant to the director: Elizaveta Svilova.[87]

- Shestaya chast mira [Шестая часть мира; A Sixth of the World (Gostorg's Import-Export. Kino-Eye's Travels through the USSR], 6 reels, 1926. [25] [26] [27] [28]. Film-poem. Produced by Goskino (Kultkino) and Sovkino (Moscow). Written and directed by Vertov. Assistant director and chief cameraman: Mikhail Kaufman. Cameramen: I. Belyakov, S. Benderski, P. Sotov, N. Constantinov, A. Lemberg, N. Strukov, I. Tolchan. Film scouts: A. Kagarlitski, I. Kopalin, B. Kudinov.[88]

- Odinnadtsatyi [Одиннадцатый; The Eleventh Year / The Eleventh], 6 reels, 1928. [29] [30]. Newsreels. Produced by the Ukrainian Film and Photography Administration (VUFKU) (Kiev). Written and directed by Vertov. Cameraman: Mikhail Kaufman. Assistant to the director: Elizaveta Svilova.[89]

- Chelovek s kino-apparatom [Человек с киноаппаратом; Man with a Movie Camera], 6 reels, 1929. [31] [32] [33] [34]. Film-feuilleton. Produced by the Ukrainian Film and Photography Administration (VUFKU) (Kiev). Written and directed by Vertov. Chief cameraman: Mikhail Kaufman. Assistant to the director: Elizaveta Svilova.[90] With the Biosphere soundtrack, 2001.

- Entuziazm: Simfoniya Donbassa [Энтузиазм: Симфония Донбаса; Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass], 6 reels, 1930. [35] [36] [37] [38]. Documentary sound film. Produced by Ukrainfilm. Written and directed by Vertov. Cameraman: B. Zeitlin. Sound engineer: P. Shtro. Assistant to the director: Elizaveta Svilova.[91]

- Tri pesni o Lenine [Три песни о Ленине; Three Songs About Lenin], 6 reels, 1934. [39] [40] [41] [42]. Documentary sound film. Produced by Mezhrabpomfilm. Written and directed by Vertov. Cameramen: D. Sourenski, M. Magidson, B. Monastyrsky. Sound engineer: P. Shtro. Score by I. Shaporin. Assistant to the director: Elizaveta Svilova.[92]

- Kolybelnaya [Колыбельная; Lullaby], 7 reels, 1937. [43] [44]. Documentary sound film. Produced by Soiuzkinokhronika. Written and directed by Vertov. Co-director: Elizaveta Svilova. Soiuzkinokhronika cameramen. Score by D. and D. Pokrass. Sound engineer: I. Renkov. Lyrics by V. Lebedev-Kumach.[93]

- Pamyati Sergo Ordzhonikidze [Памяти Серго Орджоникидзе; In Memory of Sergo Ordzhonikidze], 2 reels, 1937. [45]. Special issue. Produced by Soiuzkinokhronika. Editor: Vertov. Co-director: Elizaveta Svilova.[94]

- Sergo Ordzhonikidze [Серго Орджоникидзе; Sergo Ordzhonikidze], 5 reels, 1937. Documentary sound film. Produced by Soiuzkinokhronika. Directed by Vertov, I. Bliokh, E. Svilova, V. Dobronitsky, Soloviev, Abjibeliachvili. Score by I. Dunayevsky. Sound engineers: I. Renkov, S. Semenov. Musical arrangements by D. Blok. Lyrics by Lebedev-Kumach.[95]

- Hail the Soviet Heroines!, 1 reel, 1938. Special issue. Produced by Soiuzkinokhronika. Written and directed by Vertov. Co-director: Elizaveta Svilova. Soiuzkinokhronika cameramen.[96]

- Tri geroini [Три героини; Three Heroines], 7 reels, 1938. Documentary sound film. Produced by Soiuzkinokhronika. Script by Vertov and Elizaveta Svilova. Directed by Vertov. Chief-cameraman: S. Semenov, with staff of Moscow, Khabarovsk and Novosibirsk newsreel studios. Train views: M. Troyanovsky. Score by D. and D. Pokrass. Sound engineers: A. Kampovski, Fomine, Korotkevitch. Lyrics by Lebedev-Kumach. Assistant to the director: S. Semov.[97]

- V rayone vysoty A [In the High Zone], 1941. Film-reportage shot on the front of the Great Patriotic War (Film-Newspaper no. 87). Produced by the Central Newsreel Studio. Directed by Vertov. Cameramen: T. Bunimovitch, P. Kassatkin.[98]

- Krov za krov, smert za smert [Кровь за кровь, смерть за смерть; Blood for Blood, Death for Death (The Misdeeds of the Fascist Invaders in the USSR)], 1 reel, 1941. Produced by the Central Newsreel Sutdio. Filmed by cameramen serving at the front. Directed by Vertov.[99]

- На линии огня - операторы кинохроники [Newsreel Cameraman in the Line of Fire], 1941. Film-reportages shot on the fronts of the Great Patriotic War. (Film-Newspaper no. 77). Written and directed by Vertov. Co-director: Elizaveta Svilova. Aerial sequences by N. Vikhirev.[100]

- Kazakhstan - frontu! [Казахстан — фронту!; To You, Front! (Kazakhstan for the Front)], 5 reels, 1942. [46]. Documentary sound film. Produced by the Alma-Ata Film Studio. Written and directed by Vertov. Co-director: Elizaveta Svilova. Chief cameraman: B. Pumpiansky. Score by G. Popov, V. Velikanov. Sound engineer: K. Bakk. Lyrics by V. Lougovskoy.[101]

- V gorakh Ala-Tau [В горах Ала-Тау; In the Mountains of Ala-Tau], 2 reels, 1944. Documentary sound film. Produced by the Alma-Ata Film Studio. Written and directed by Vertov. Cameraman: B. Pumpiansky. Co-director: Elizaveta Svilova.[102]

- Klyatva molodykh [Клятва молодых; The Oath of Youth], 3 reels, 1944. Produced by the Central Documentary Film Studio. Directed by Vertov, Elizaveta Svilova. Cameramen: I. Belyakov, G. Amirov, B. Borkovsky, B. Dementiev, S. Semenov, V. Kossitsyn, E. Stankevitch.[103]

- Novosti dnya [Новости дня; Daily News], 1944-54. Film-newspaper. Produced by the Central Documentary Film Studio. Vertov's involvement was occasional. 1944: no. 18; 1945: nos. 4, 8, 12, 15, 20; 1946: nos. 2, 8, 18, 24, 34, 52, 67, 71; 1947: nos. 6, 13, 21, 30, 37, 48, 51, 65, 71; 1948: nos. 8, 19, 23, 29, 34, 39, 44, 50; 1949: nos. 19, 27, 43, 45, 51, 55; 1950: nos. 7, 58; 1951: nos. 15, 33, 43, 54; 1952: nos. 9, 15, 31, 43, 54; 1953: nos. 18, 27, 35, 55; 1954: nos. 31, 46, 60.[104]

- DVDs

- Man with the Movie Camera, DVD, Film Preservation Associates, 1998; 2002. Score by The Alloy Orchestra. Audio commentary track by Yuri Tsivian. [47]

- The Cinematic Orchestra, Man With A Movie Camera, DVD, Ninja Tune, 2003. [48] [49]

- Man with a Movie Camera, DVD, 2005, Madman Films. With Three Songs about Lenin. Score by Michael Nyman. [50] [51]

- Entuziazm (Simfonija Donbassa), 2-disc DVD, Edition Filmmuseum 01, 2005; 2nd ed., 2006; 3rd ed., 2007. Restored version and unrestored version plus documentary on Peter Kubelka's restoration (65 min). [52] [53]

- Sestaja cast' mira & Odinnadcatyj, 2-disc DVD, Edition Filmmuseum 53, 2009; 2nd ed., 2010. Both films with score by Michael Nyman. [54] [55]

- Landmarks of Early Soviet Film: A 4-Disc DVD Collection of 8 Groundbreaking Films: 1924-1930, with Vertov's Stride, Soviet!, Flicker Alley, 2011. [56] [57]

Sound recordings[edit]

- on UbuWeb: Enthusiasm! (1930), Laboratory Of Hearing (1916), Radio-Ear / Radio-Pravda (1916).

Bibliography[edit]

Articles and talks by Vertov (selection)[edit]

- "My. Variant manifesta" [Мы, Вариант манифеста], Kino-fot [Кино-Фот] 1 (25 August 1922), pp 11-12; repr. in Vertov, Statii, dnevniki, zamysly, ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, pp 45-49. [58] [59]. The first appearance in print of the program of the kinok-documentalist group formed by Vertov in 1919. As Vertov testifies, the original conception for the manifesto goes back to 1919. In the article "From Kino-Eye to Radio-Eye" he writes: "Moscow. The end of 1919. An unheated room. A small vent-window with a broken pane. Next to the window a table. On the table, a glass of yesterday's undrunk tea that has turned to ice. Near the glass is a manuscript. We read: 'Manifesto on the Disarmament of Theatrical Cinematography.' One of the variants of this manifesto, entitled 'WE', was later (1922) published in the magazine Kinofot (Moscow)."[105] The article includes two illustrations: one of a "bespredmetnaja grafika" [abstract drawing] by Aleksandr Rodchenko, dating from 1915, the second is the diagram intended to illustrate Vertov's concept of the interval. (Russian)

- "Wir. Variante eines Manifestes", in Aufsätze, Tagebücher, Skizzen, 1967, pp 55-57; repr. in Texte zur Theorie des Films, ed. Franz-Josef Albersmeier, Reclam, 1998, pp 31-35. (German)

- "Variationer på ett manifest", trans. Carl Henrik Svenstedt, in Film: en antologi, 1971, pp 29-33. (Swedish)

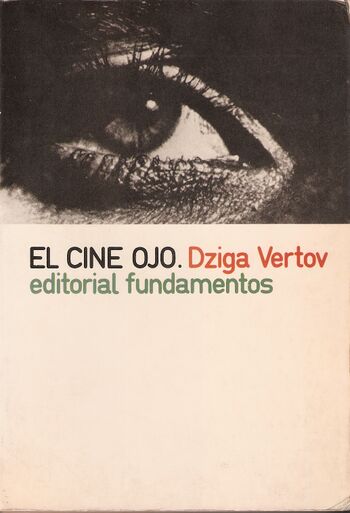

- "Nosotros: Variante del manifiesto", in El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, pp 15-19. (Spanish)

- "We: A Version of a Manifesto", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O’Brien, University of California Press, 1984, pp 5-9. (English)

- "NoS: Variante de manifesto". (Portuguese)

- "Kinoki. Perevorot", LEF 3 (1923), pp 135-143; reprinted in Statii, dnevniki, zamysly, ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, pp 50-58. Portions of a projected book by Vertov. The article is one of the more important theoretical statements made by the director during the mid-1920s. While in part developing the theses of the manifesto "WE", it sums up the creative experience that Vertov received while working on the magazines Kinonedelia [Film-week] and Kinopravda [Film-truth] and on his first short films, The Anniversary of the Revolution, The Battle of Tsaritsyn, and The Trial of Mironov. Vertov also summarizes his theoretical observations from those years on the specific nature of cinema.[106] (Russian)

- "Kinoks - Revolucion", in El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, pp 20-31. (Spanish)

- "Kinoks: A Revolution", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O’Brien, University of California Press, 1984, pp 11-21. (English)

- "Kinoki – Umsturz", in Texte zur Theorie des Films, ed. Franz-Josef Albersmeier, Reclam, 1998, pp 36-50. (German)

- "O znacenii neigrovoj kinematografii", 1923; first printed in Statii, dnevniki, zamysly, ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, pp 69-72. An abridged shorthand report of a talk by Vertov at a public debate held at ARRK [Association of Workers in Revolutionary Cinematography] on 26 September 1926.[107] (Russian)

- "La importancia del cine no interpretado", in El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, pp 45-49. (Spanish)

- "On the Significance of Nonacted Cinema", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O'Brien, University of California Press, University of California Press, 1984, pp 35-38. (English)

- "Pozhdenie Kinoglaza", dated 1924; first printed in Statii, dnevniki, zamysly, ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, pp 73-75. Theses for an article.[108] (Russian)

- "Nacimiento del cine-ojo", in El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, pp 51-53. (Spanish)

- "The Birth of Kino-Eye", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O’Brien, University of California Press, 1984, pp 40-42. (English)

- "O Kinoglaze", 1924; first printed in Statii, dnevniki, zamysly, ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, pp 75-79. An abridged shorthand report of a speech by Vertov at a conference of the kinoks on 9 June 1924. The speech clearly characterizes Vertov's attitude toward so-called intermediate trends in cinematography (according to the kinoks, the films of Eisenstein were included in this category). Calling works of this type "acted films in newsreel trousers", "surrogates", etc., Vertov saw in them a danger for the Soviet documentary. New material pertaining to the history of the film journal Kinopravda is also contained in this speech.[109] (Russian)

- "El Kinopravda", in El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, pp 53-59. (Spanish)

- "On Kinopravda", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O'Brien, University of California Press, 1984, pp 42-47. (English)

- "Kinoglaz", in Na putiakh iskusstva: Sbornik statei [On the Paths of Art], Moscow: Proletkult, 1926; repr. in Statii, dnevniki, zamysly, ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, pp 89-104. Slightly abridged.[110] (Russian)

- "Cine-ojo", in El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, pp 71-89. (Spanish)

- "Kino-Eye", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O’Brien, University of California Press, 1984, pp 60-79. (English)

- "Kinoglaz", in Aufsätze, Tagebücher, Skizzen, 1967; repr. in Texte zur Theorie des Films, ed. Franz-Josef Albersmeier, Reclam, 1998, pp 51-53. (German)

- "Chelovek s kino-apparatom", dated 1928; first printed in Statii, dnevniki, zamysly, ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, pp 106-109. Theses for an article.[111] (Russian)

- "El hombre de la camara", in El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, pp 92-94. (Spanish)

- "The Man with the Movie Camera", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O'Brien, University of California Press, 1984, pp 82-85. (English)

Vertov's selected writings[edit]

- Statii, dnevniki, zamysly [Статьи. Дневники. Замыслы], ed. Sergei Drobashenko, Moscow: Izd. Iskusstva, 1966, 320 pp. (Russian)

- Aufsätze, Tagebücher, Skizzen, ed. Hermann Herlinghaus, Leipzig: Institut für Filmwissenschaft, 1967, 375 pp. (German)

- Articles, journaux, projets, trans. Sylviane Mossé and Andrée Robel, Paris: Union générale d'éditions, 1972, 442 pp. (French)

- El cine-ojo, trans. Francisco Llinas, Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos, 1973, 215 pp. (Spanish)

- Człowiek z kamerą: wybór pism, trans. Tadeusz Karpowski, Warsaw: Wydawn. Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1976, 291 pp. (Polish)

- Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, University of California Press, 1984, 408 pp. (English)

- Aus den Tagebüchern, eds. Peter Konlechner and Peter Kubelka, Vienna: Österreichisches Filmmuseum, 1967, 150 pp. (German)

- Schriften zum Film, Munich: Hanser, 1976, 170 pp. (German)

- Tagebücher, Arbeitshefte, eds. Thomas Tode and Alexandra Gramatke, UVK: Konstanz, 2000, 276 pp. Foreword, [60] (German)

- Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, ed. Yuri Tsivian, trans. Julian Graffy, Gemona: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004, xv+422 pp. (English)

- Iz nasledia 1: Dramaturgicheskeie opyty [Из наследия. Том 1. Драматургические опыты], ed. Aleksander Deriabin (Александр Дерябин), Moscow: Eisenstein Centre, 2004, 536 pp. (Russian)

- Iz nasledia 2: Statii i vystupleniia [Из наследия. Том 2. Статьи и выступления], eds. D.V. Kruzhkova (Д. В. Кружкова) and S.M. Ishevskaia, Moscow: Eisenstein Centre, 2008, 648 pp. (Russian)

- Memorias de un cineasta bolchevique, trans. Joaquín Jordà, Madrid: Capitán Swing Libros, 2009. (Spanish)

- L'occhio della rivoluzione. Scritti dal 1922 al 1942, ed. Pietro Montani, Mimesis, 2011, 276 pp. (Italian)

Books on Vertov[edit]

- Nikolai Abramov (Николай Абрамов), Dziga Vertov [Джига Вертов], Moscow: Izd. Akademii Nauk, 1962, 165 pp. (Russian)

- Dziga Vertov, trans. Barthelemy Amengual, Lyon: Serdoc, 1965. (French)

- Luda and Jean Schnitzer, Dziga Vertov, 1896-1954, Paris: Anthologie du cinema, 1968. (French)

- Georges Sadoul, Dziga Vertov, Paris: Champ libre, 1971, 171 pp. Preface by Jean Rouch. (French)

- El cine de Dziga Vertov, Era, 1973, 223 pp. (Spanish)

- V. Listov, Istoriia smotrit v obiektiv, Moscow, 1973. On Vertov as documentarian and film journalist. (Russian)

- Antonín Navrátil, Dziga Vertov. Revolucionář dokumentárního filmu, Prague: Čs. filmový ústav, 1974, 252 pp. (Czech)

- Pietro Montani, Dziga Vertov, Firenze: La nuova Italia, 1975, 139 pp. (Italian)

- Elizabeta Ignatyevna Vertova-Svilova (Елизавета Игнатьевна Вертова-Свилова), Anna L. Vinogradova (Анна Львовна Виноградова) (eds.), Dziga Vertov v vospominanijach sovremennikov [Дзига Вертов в воспоминаниях современников; Dziga Vertov in the Reminiscences of His Contemporaries], Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1976, 280 pp. (Russian)

- Dontsho Hitrov (ed.), Dziga Vertov, Sofia: Bulgarska natsionalna filmoteka, 1977, 80 pp. (Bulgarian)

- Seth Feldman, Evolution of Style in the Early Work of Dziga Vertov, New York: Arno Press, 1977, 233 pp. A facsimile reprint of a Ph.D. dissertation. (English)

- Seth Feldman, Dziga Vertov, A Guide to References and Resources, Boston: G.K.Hall, 1979, 232 pp. A chronological survey of Vertov's career with annotated filmography and bibliography. (English)

- Vasco Granja, Dziga Vertov, Livros Horizonte, 1981, 96 pp. Excerpt. (Portuguese)

- Lev Roshal (Лев Моисеевич Рошаль), Dziga Vertov [Дзига Вертов], Moscow, 1982, 263 pp. (Russian)

- Vlada Petrić, Constructivism in Film: The Man with the Movie Camera: A Cinematic Analysis, Cambridge University Press, 1987, 337 pp; 2nd ed., 2012. (English)

- Frédérique Devaux, L'Homme à la caméra de Dziga Vertov, Brussels: Yellow Now, 1990, 126 pp. (French)

- Jean-Pierre Esquenazi (ed.), Vertov: L'invention du réel!, Paris: L'Harmattan, 1997, 286 pp. (French)

- Natascha Drubek-Meyer, Jurij Murasov (eds.), Apparatur und Rhapsodie: zu den Filmen des Dziga Vertov, Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2000, 283 pp. [61] (German)

- François Zourabichvili, "The eye of montage: Dziga Vertov and Bergsonian materialism", in The brain is the screen: Deleuze and the philosophy of cinema, ed. Gregory Flaxman, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. (English)

- Graham Roberts, The Man with the Movie Camera, London: I. B. Tauris, 2001, 108 pp. (English)

- Yuri Tsivian (ed.), Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, trans. Julian Graffy, Gemona: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004, xv+422 pp. (English)

- Thomas Tode, Barbara Wurm, Österreichisches Filmmuseum (eds.), Dziga Vertov. The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum / Dziga Vertov. Die Vertov-Sammlung im Österreichischen Filmmuseum, Vienna: Austrian Film Museum/SYNEMA, 2006, 288 pp. TOC, [62]. (German)/(English)

- Klemens Gruber (ed.), Verschiedenes über denselben: Dziga Vertov 1896-1954, Vienna/Cologne/Weimar: Böhlau, 2006, 125 pp. TOC. (German)

- Jeremy Hicks, Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film, London & New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007. (English)

- Peggy Ahwesh, Keith Sanborn (eds.), Vertov from Z to A, trans. Keith Sanborn, New York: Ediciones la Calavera, 2008, 169 pp. (English)

- David Tomas, Vertov, Snow, Farocki: Machine Vision and the Posthuman, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, 304 pp. (English)

- Kino-oko. Wokół Wiertowa i konstruktywizmu / Kino-Eye. Around Vertov and Constructivism, Białystok: Galeria Arsenał, 2017, 79 pp. Exh. cat. Exhibition. (Polish)/(English)

- John MacKay, Dziga Vertov: Life and Work (Volume 1: 1896-1921), Academic Studies Press, 2018, xcvi+372 pp. Publisher. Reviews: Morley (SEER), Belodubrovskaya (New Rev Film & TV Stud), Williams (Filmint), Liebman (Cineaste). [63] (English)

Journal issues devoted to Vertov[edit]

- Maske und Kothurn 42:1 (1996), Special Issue: "Dziga Vertov zum 100. Geburtstag", ed. Klemens Gruber, Vienna: Böhlau 1996. Proceedings from the Vertov-Symposium Wien 1996. (German)

- Maske und Kothurn 50:1 (2004), Special Issue: "Der kreiselnde Kurbler. Dziga Vertov zum 100. Geburtstag Bd. 2: Vorträge und Gespräche des Vertov-Symposiums in Wien", eds. Klemens Gruber and Aki Beckmann, Vienna: Böhlau 1996. (German)

- October 121: "New Vertov Studies", eds. Annette Michelson and Malcolm Turvey, Summer 2007. TOC. (English)

- Malcolm Turvey, "Vertov: Between the Organism and the Machine", pp 5-18. (English)

- Simon Cook, "Our Eyes, Spinning Like Propellers: Wheel of Life, Curve of Velocities, and Dziga Vertov's Theory of the Interval", pp 79–91. (English)

- Maske und Kothurn 55:3 (2009), Special Issue: "Digital Formalism. Die kalkulierten Bilder des Dziga Vertov", eds. Klemens Gruber and Barbara Wurm with Vera Kropf, Vienna: Böhlau, 230 pp. (German) [64]

Book chapters, papers and articles on Vertov[edit]

- Vertov's biographies

- Herbert Marshall, "Dziga Vertov", in Masters of the Soviet Cinema: Crippled Creative Biographies, Routledge, 1983; 2013, pp 61-97. (English)

- Annette Michelson, "Introduction", in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, University of California Press, 1984, pp xv-lxi. (English)

- Petrić, "Appendix 4: Biographical sketch of Vertov's career, 1896-1954", in Constructivism in Film, 1987, pp 221-228. (English)

- Jonathan Dawson, "Dziga Vertov", Sense of Cinema, 2003. (English)

- John MacKay, "Dziga Vertov (1896-1954)", in Russia's People of Empire, eds. Stephen M. Norris and Willard Sunderland, Indiana University Press, 2012, pp 282-294. [65] (English)

- On Vertov's early life

- Valerie Pozner, "Vertov before Vertov: Psychoneurology in Petrograd", in Dziga Vertov: The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum, eds. Thomas Tode and Barbara Wurm, 2006, pp 12-15. (English)

- On Vertov's poetry

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 33-37. (English)

- On Kino-Pravda

- Aleksei Gan, Da zdravstvuet demonstratsiia byta! [Да здравствует демонстрация быта!; Long Live the Demonstration of Everyday Life!], Moscow: Goskino, 1923, 16 pp (edition of 2000), JPG. An ideological pamphlet emphasizing the political significance of Vertov's Kino-Pravda series; includes a still of Trotsky on a tribune taken from Kino-Pravda 13 (1923). (Russian)

- Seth Feldman, "Cinema weekly and Cinema truth; Dziga Vertov and the Leninist proportion", Sight and Sound 43:1 (Winter 1973/1974), pp 34-37. A study of Vertov's newsreel series and assessment of his influence on later Soviet filmmakers. (English)

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 40-80. (English)

- On Kino-Eye

- Roshal', Dziga Vertov, 1982, pp 103-111. (Russian)

- Joseph Christopher Schaub, "Presenting the Cyborg's Futurist Past: An Analysis of Dziga Vertov's Kino-Eye", Postmodern Culture 8:2 (January 1998). (English)

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 99-122. (English)

- Hicks, Defining Documentary Films, 2007, pp 15-20. (English)

- John MacKay, "Vertov and the Line: Art, Socialization, Collaboration", in Film, Art, New Media: Museum Without Walls?", ed. Angela Dalle Vacche, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp 81-96. (English)

- John MacKay, "Kinoglaz (Vertov, 1924)", in Il cinema russo attraverso i film, eds. Alessia Cervini and Alessio Scarlato, Rome: Carocci, 2013. (Italian). Translated from English.

- Kristin Romberg, "Labor Demonstrations: Aleksei Gan's Island of the Young Pioneers, Dziga Vertov's Kino-Eye, and the Rationalization of Artistic Labor", October 145 (Summer 2013), pp 38-66. (English)

- On Vertov and Constructivism

- Yuri Tsivian, "Turning Objects, Toppled Pictures: Give and Take between Vertov's Films and Constructivist Art", October 121 (Summer 2007), pp 92-110. (English)

- On Vertov and LEF

- Natasha Kolchevska, "The Faktoviki at the Movies: Novyj Lef's Critique of Ejzenstejn and Vertov", Russian Language Journal 41:138-139 (1987), pp 139-151. (English)

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 265-287. (English)

- On Vertov's relationship to Eisenstein

- Petrić, Constructivism in Film, 1987, pp 48-60. (English)

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 125-152. (English)

- On Stride, Soviet!

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 157-181. (English)

- John MacKay, "Stride Soviet (1926) and Vertovian Technophobia", 2008. (English)

- On One Sixth of the World

- Joseph Freeman, "The Soviet Cinema", in Voices of October: Art and Literature in Soviet Russia, New York: Vanguard, 1930, pp 217-264. (English)

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 182-250. (English)

- Oksana Sarkisova, "Across One Sixth of the World: Dziga Vertov, Travel Cinema, and Soviet Patriotism", October 121 (Summer 2007), pp 19-40. (English)

- Irina Sandomirskaia, "One Sixth of the World: Avant-garde Film, the Revolution of Vision, and the Colonization of the USSR Periphery during the 1920s (Towards a Postcolonial Deconstruction of the Soviet Hegemony)", in From Orientalism to Postcoloniality, ed. Kerstin Olofsson, Huddinge: Södertörns högskola, 2008, pp 8-31. (English)

- On The Eleventh Year

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 288-317. (English)

- John MacKay, "Film Energy: Process and Metanarrative in Dziga Vertov’s The Eleventh Year (1928)", October 121 (Summer 2007), pp 41-78. (English)

- Devin Fore, "The Metabiotic State: Dziga Vertov's The Eleventh Year", October 145 (Summer 2013), pp 3-37. (English)

- On Man with a Movie Camera

- Annette Michelson, "From Magician to Epistemologist: Vertov's The Man With a Movie Camera", Artforum 10:7 (1972), pp 60-72; repr. in The Essential Cinema, ed. P. Adams Sitney, New York University Press and Anthology Film Archives, 1975, 95-111; repr., October 162, Fall 2017, pp 112-132. (English)

- Noel Carroll, "Causation, the Ampliation of Movement and Avant-garde Film", Millennium 10-11 (Fall-Winter 1981/82), pp 61-82. (English)

- Stephen Crofts, Olivia Rose, "An Essay Towards Man with a Movie Camera", Screen 18 (1977), pp 9-60. (English)

- Martin F. Norden, "The Avant-garde cinema of the 1920s: connections to Futurism, Precisionism, and Suprematism", Leonardo 17:2 (1984) pp 108-112. (English)

- Petrić, Constructivism in Film: The Man with the Movie Camera: a Cinematic Analysis, 1987. (English)

- Jonathan L. Beller, "The Circulating Eye", Communication Research 20:2 (April 1993), pp 298-313. (English)

- Yuri Tsivian, "Dziga Vertov's Frozen Music", Griffithiana 54 (October 1995) pp 92-121. Cue sheets and a music scenario for Chelovek s kinoapparatom from Vertov's archive at Russia's State Archive of Literature. Reproduces Vertov's handwritten notes. (English)

- Seth Feldman. "'Peace Between Man and Machine': Dziga Vertov's The Man with a Movie Camera.", in Documenting the Documentary: Close Readings of Documentary Film and Video, eds. Barry Keith Grant and Jeannette Sloniowski, Wayne State University Press, 1998, pp 40-53. (English)

- Jonathan L. Beller, "Dziga Vertov and the Film of Money", Boundary 2 26:3 (1999), pp 151-199. "The films of Dziga Vertov portray capitalist cinema as influencing the unconscious, rendering the viewer susceptible to any ideal the filmmaker chose to insert. His 1929 Man with a Movie Camera suggested an alternative circulation of value, and although that did not prove viable, cinema retains the power to transform all aspects of political economy." (English)

- Malcolm Turvey, "Can the Camera See? Mimesis in Man With a Movie Camera", October 89 (Summer 1999). (English)

- Pearl Latteier, "Gender and the Modern Body: Men, Women and Machines in Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera", Post Script: Essays in Film and the Humanities 22:1 (Fall 2002), pp 23-34. (English)

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 318ff. (English)

- Anne Nesbet, "Understanding Man With a Movie Camera", Film Quarterly 59:1 (Fall 2005), p 3. Discusses Yuri Tsivian's project of bringing hundreds of films and some rare manuscripts by Dziga Vertov to the 23rd Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Sacile, Italy, in October 2004. (English)

- Sergio Delgado, "Dziga Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera and the Phenomenology of Perception", Film Criticism 34:1 (2009), pp 1-16. (English)

- Anke Hennig, "Čelovek s kinoapparatom", in Noev kovčeg russkogo kino. Ot 'Sten'ki Razina' do 'Stiljag', eds. Ekaterina Vassilieva and Nikita Braguinski, Vinnytsia: Globus, 2012, pp 77-82. (Russian)

- John MacKay, "Man with a Movie Camera: An Introduction", 2013. (English)

- David Tomas, Vertov, Snow, Farocki, 2013. (English)

- Malcolm Turvey, "City Symphony and Man With a Movie Camera", in The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s, MIT Press, 2013, pp 135-161. (English)

- On Vertov's European travels

- Thomas Tode, "Ein Russe projiziert in die Planetariumskuppel: Dsiga Wertows Reise nach Deutschland", in Die ungewöhnlichen Abenteuer des Dr. Mabuse im Lande der Bolschewiki, ed. Oksana Bulgakova, Berlin: Freunde der Deutschenn Kinemathek, 1995, pp 143-51. (German)

- Thomas Tode, "Ein Russe auf dem Eifelturm: Vertov in Paris", in Apparatur und Rhapsodie: Zu den Filmen des Dziga Vertov, pp 43-72. (German)

- On Vertov's departure from Sovkino

- Tsivian, Lines of Resistance, 2004, pp 252-262. (English)

- On Enthusiasm

- Lucy Fischer, "Enthusiasm: From Kino-Eye to Radio-Eye", Film Quarterly 31:2 (Winter 1977-78), pp 25-34. Discusses Vertov's theories regarding sound and image and their relationship, using as an example his then recently reconstructed film. (English)

- Lucy Fischer, "Restoring 'Enthusiasm'" (Interview), Film Quarterly 31:2 (Winter 1977-78), pp 35-36. Peter Kubelka describes the restoration of Enthusiasm. (English)

- Scott Bukatman, "Battles with Songs: The Soviet Historical Film as Historical Document", in Persistence of Vision 3-4 (Summer 1986), pp 23-34. (English)

- John MacKay, "Disorganized Noise: Enthusiasm and the Ear of the Collective", KinoKultura 7, Jan 2005, p 51. (English)

- Devin Fore, "Dziga Vertov, The First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema", Configurations 18:3 (2010), pp 363-382. (English)

- Andrey Smirnov, "Dziga Vertov - Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass", in Smirnov, Sound in Z: Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Early 20th-century Russia, London: Koenig Books & Sound and Music, 2013, pp 166-167. (English)

- Lilya Kaganovsky, "The Materiality of Sound: Dziga Vertov's Enthusiasm and Esfir Shub's K.Sh.E.", ch 2 in Kaganovsky, The Voice of Technology: Soviet Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1928-1935, Indiana University Press, 2018, pp 70-107. (English)

- On Three Songs about Lenin

- Anna-Lena Wilbom, "Tre sånger om Lenin: sex stillbilder, filmtexter och dagboksanteckningar", Chaplin 6 (1972), Stockholm, pp 217-223. (Swedish)

- Annette Michelson, "The Kinetic Icon in the Work of Mourning: Prolegomena to the Analysis of a Textual System", October 52 (Spring 1990), pp 16-39. (English)

- Vlada Petrić, "Vertov, Lenin And Perestroika - The Cinematic Transposition Of Reality", Historical Journal Of Film Radio And Television 15:1 (March 1995), pp 3-17. Analysis of Vertov's films and ideas, concerned particularly with Tri pesni o Lenine, discussing how he represented reality in an attempt to change the people's consciousness. (English)

- Mariano Prunes, "Dziga Vertov's Three Songs about Lenin (1934): A Visual Tour through the History of the Soviet Avant-Garde in the Interwar Years", Criticism 45:2 (Spring 2003). (English)

- John MacKay, "Allegory and Accommodation: Vertov's Three Songs of Lenin (1934) as a Stalinist Film", Film History: An International Journal 18:4 (2006), pp 376-391. [66] (English)

- Lilya Kaganovsky, "“Les Silences de la voix”: Dziga Vertov's Three Songs of Lenin", ch 5 in Kaganovsky, The Voice of Technology: Soviet Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1928-1935, Indiana University Press, 2018, pp 178-226. (English)

- On Lullaby

- John MacKay, "The subjective camera in Vertov's Lullaby (1937)", 2013. Talk. (English)

- Historical overview of Vertov reception

- John MacKay, "The 'Spinning Top' Takes Another Turn: Vertov Today", KinoKultura 8 (April 2005). (English)

- On Dziga Vertov Group

- Jane de Almeida (ed.), Grupo Dziga Vertov, Sao Paulo: Witz, 2005. (Brazilian Portuguese)

- Jean-Luc Godard y el Grupo Dziga Vertov, 1968-1974, Barcelona: Prodimag, 2008, 61 pp. Booklet for videodiscs set. [67] (Spanish)

- On Vertov's films as database cinema

- Lev Manovich, "Database as a Symbolic Form", Convergence 80:5, 1999, pp 80-99. (English)

- Lev Manovich, "Prologue: Vertov's Dataset", in The Language of New Media, MIT Press, 2001, pp xiv-xxxvi. (English)

- Seth Feldman, "Vertov After Manovich", Canadian Journal of Film Studies 16:1 (Spring 2007), pp 39-50. (English)

- More

- Kazimir Malevich, "I likuyut liki na ekranakh" [И ликуют лики на экранах; And Images Triumph on the Screen], Киножурнал АРК 10 (1925), pp 8-9. Compares Vertov and Eisenstein. (Russian)

- "And Visages Are Victorious on the Screen", in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (Russian)/(English)

- Kazimir Malevich, "Zhivopisnye zakony v problemakh kino" [Живописные законы в проблемах кино], Kino i kul'tura [Кино и культура] 7-8 (1929), pp 22-26. (Russian)

- "Painterly Laws in the Problems of Cinema", trans. Cathy Young, in Margarita Tupitsyn, Malevich and Film, Yale University Press, 2002, pp 147-159. (English)

- "Pictorial Laws in Cinematic Problems", in The White Rectangle: Writings on Film, ed. Oksana Bulgakowa, Potemkin Press, 2002. (Russian)/(English)

- Tamara Selezneva, "Nasledie Dzigi Vertova i iskaniia 'cinéma-vérité'" [The Heritage of Dziga Vertov and the Aspiration of 'cinéma vérité'], in Razmyshleniia u ekrana, ed. E.S. Dobin, St. Petersburg: Iskusstvo, 1966, pp 337-367. Compares Vertov's work and method with that of Rouch, Leacock, and Pennebaker. (Russian)

- Sergej I. Jutkevic, "Dziga Vertov", in Le cinema sovietique par ceux qui l'ont fait, eds. Luda and Jean Schnitzer and Marcel Martin, Paris: Les editeurs francais reunis, 1966. (French)

- Cinema in Revolution: The Heroic Era of the Soviet Film, trans. David Robinson, London: Secker & Warburg, 1973. (English)

- M. Enzensberger, "Dziga Vertov", Screen 13:4 (Winter 1972-73), pp 90-107. (English)

- Richard M. Barsam, "Beginnings of the Soviet Propagandist Tradition: Dziga Vertov", in Nonfiction Film: A Critical History, E.P. Dutton, 1973; rev. & exp.ed., Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992, pp 66-75. (English)

- Erik Barnouw, Documentary: a History of the Non-fiction Film, Oxford University Press, 1974. (English)

- Malcolm Le Grice, Abstract Film and Beyond, MIT Press, 1977. (English)

- Vlada Petrić, "Dziga Vertov as Theorist", Cinema Journal 18:1 (Autumn 1978), pp 29-44. Analysis of Vertov's early writings in relation to his film Man with a Movie Camera. (English)

- Anna Lawton, "Rhythmic Montage in the Films of Dziga Vertov: A Poetic Use of the Language of Cinema", Pacific Coast Philology, Vol. 13 (October 1978), pp 44-50. (English)

- Alan Williams, "The Camera-Eye and the Film: Notes on Vertov's Formalism", Wide Angle 3 (1979), pp 12-17. (English)

- Peter Weibel, "Eisenstein, Vertov and the Formal Film", trans. Phillip Drummond, in Film as Film: Formal Experiment in Film, 1910-1975, London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1979, pp 46-51. (English)

- Gilles Deleuze, "Towards a gaseous perception", in Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam, University of Minnesota Press, 1986, pp 80-86, n229-230. (English)

- Ben Singer. "Connoisseurs of Chaos: Whitman, Vertov and the 'Poetic Survey'", Literature/Film Quarterly 15:4 (Fall 1987), pp 247-258. (English)

- L. Kirby, "From Marinetti to Vertov: Woman on the Track of Avant-garde Representation", Quarterly Review of Film Studies 10:4 (April 1989), pp 309-323. The ambiguous depiction of woman as (or opposed to) machine in futurist theory and avant-garde films such as Man with a Movie Camera. (English)

- Jeremy Murray-Brown, "False Cinema: Dziga Vertov and Early Soviet Film", The New Criterion 8:3 (November 1989), pp 21-33. (English)

- Vlada Petrić, "The Vertov Dilemma: Film-Eye vs Film-Truth", Spectator 12:1 (Fall 1991), pp 6-17. [68] (English)

- Patricia R. Zimmermann, "Strange Bedfellows - The Legacy Of Vertov And Flaherty (Introduction To Soviet And American Documentary Film Seminar)", Journal Of Film And Video 44:1-2 (Spring-Summer 1992), pp 4-8. (English)

- Patricia R. Zimmermann, "Reconstructing Vertov: Soviet Film Theory and American Radical Documentary", Journal of Film and Video 44:1-2 (Spring-Summer 1992), pp 80-90. (English)

- William C. Wees, "The Camera-Eye: Dialectics of a Metaphor", in Light Moving in Time: Studies in the Visual Aesthetics of Avant-Garde Film, University of California Press, 1992, pp 11-30. [69] (English)

- Philip Vilas Bohlman, Music, Modernity, and the Foreign in the New Germany, 1994, pp 121-152. (English)

- Vlada Petrić, "Vertov's Cinematic Transposition of Reality", in Beyond Document: Essays on Nonfiction Film, ed. Charles Warren, Wesleyan University Press, 1996, pp 271-294. (English)

- Douglas Kahn, "Russian Revolutionary Film", in Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts, MIT Press, 1999, pp 139-156. (English)

- Oksana Sarkisova, "Present Perfect or Present Progressive? Temporality in Early Soviet Avant-Garde Visual Arts", Studies in Slavic Cultures 1 (January 2000), pp 103-132. (English)

- Thomas W. Sheehan, "Wittgenstein and Vertov: Aspectuality and Anarchy", Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture 24:3 (Fall 2002), pp 95-113. (English)

- Marina Goldovskaya (Марина Голдовская), Zhenshchina s kinoapparatom [Женщина с киноаппаратом], Moscow: Materik (Материк), 2002, 251 pp. [70] (Russian)

- Woman with a Movie Camera: My Life as a Russian Filmmaker, trans. Antonina W. Bouis, forew. Robert Rosen, University of Texas Press, 2006. (English)

- Nicole Armour, "The Machine Art of Dziga Vertov and Busby Berkeley", Images 5, c2004. (English)

- Malcolm Turvey, "The Revelationist Tradition: Exegesis: II", in Doubting Vision Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp 31-37. (English)

- Yates McKee, "Post-Communist Notes on Some Vertov Stills", in Communities of Sense: Rethinking Aesthetics and Politics, eds. Beth Hinderliter, et al., Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2009, pp 267-293. (English)

- Kirill Medvedev (Кирилл Медведев), Kirill Adibekov (Кирилл Адибеков), борьба на два фронта. жан-люк годар и группа дзига вертов, 1968-1972, свободное марксистское издательство, 2010. (Russian) (Russian)

- John MacKay, "A Revolution in Film", Artforum (April 2011), pp 196-203, n238. (English)

- Klemens Gruber, "Das überrumpelte Leben. Dziga Vertov als Choreograph", in Versehen. Tanz in allen Medien, eds. Helmut Ploebst and Nicole Haitzinger, Munich: epodium, and Vienna: corpus, 2011, pp 34-51. (German)

- Christian Quendle, "Rethinking the camera eye: dispositif and subjectivity", New Review of Film and Television Studies 9:4 (December 2011), pp 395-414. (English)

- Joshua Malitsky, "The Dialectics of Thought and Vision in the Films of Dziga Vertov, 1922-1927", in Post-Revolution Nonfiction Film: Building the Soviet and Cuban Nations, Indiana University Press, 2013. [71] (English)

- Andrey Smirnov, Sound in Z: Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Early 20th-century Russia, London: Koenig Books & Sound and Music, 2013. (English)

- "The Laboratory of Hearing", pp 25-28. (English)

- John MacKay, "Built on a Lie: Propaganda, Pedagogy, and the Origins of the Kuleshov Effect", in The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies, 2013, pp 215-232. (English)

- Lev Manovich, "Visualizing Vertov", 2013, 38 pp. (English)

- Karen Pearlman, John MacKay, John Sutton, "Creative Editing: Svilova and Vertov's Distributed Cognition", Apparatus 6: "Women at the Editing Table: Revising Soviet Film History of the 1920s and 1930s", eds. Adelheid Heftberger and Karen Pearlman, Berlin, 2018. (English)

- Articles on Vertov on Seance.ru. (Russian)

Bibliographies[edit]

- Dziga Vertov, East European Cinema: A Bibliography of Materials in the UC Berkeley Library (English)

Documentary films about Vertov[edit]

- Mir bez igry [Мир без игры], dir. Sergei Drobashenko, 54 min, 1966. [72] (Russian)

- Dziga Vertov, dir. Peter Konlechner (director of the Austrian Film Museum), 60 min, 1974. Includes footage of Svilova commenting on the excerpts from Vertov's films and their cooperation.

- Dziga i yego brat'ya [Дзига и его братья], dir. Evgeny Tsymbal, 2002. (Russian)

- Vse Vertovy [Все Вертовы], dir. Vladimir Nepevny, 2002. (Russian)

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Goldovskaya 2006, p. 253

- ↑ MacKay 2012a

- ↑ MacKay 2014

- ↑ Smirnov 2013

- ↑ MacKay 2012a, p. 284

- ↑ Michelson 1984, p. xxiii

- ↑ Smirnov 2013a, p. 25

- ↑ MacKay 2012a, p. 284

- ↑ Smirnov 2013a, p. 25

- ↑ MacKay 2012a, p. 285

- ↑ MacKay 2012a, p. 285

- ↑ Smirnov 2013a, p. 25

- ↑ Speech, 5 April 1935, in Vertov, Iz Nasledia 2, 2008, p 291. Trans. Andrey Smirnov.

- ↑ Smirnov 2013a, p. 25

- ↑ Speech, 5 April 1935, in Vertov, Iz Nasledia 2, 2008, p 291. Trans. Andrey Smirnov.

- ↑ Smirnov 2013a, p. 25

- ↑ Smirnov 2013a, pp. 25-26

- ↑ Michelson 1984, p. xxiii