Difference between revisions of "Cybernetic Serendipity"

m (Text replacement - "sci-hub.tw" to "sci-hub.se") |

m (Text replacement - "sci-hub.se" to "sci-hub.st") |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Reichardt_Jasia_ed_Cybernetic_Serendipidity_The_Computer_and_the_Arts.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Reichardt_Jasia_ed_Cybernetic_Serendipidity_The_Computer_and_the_Arts.jpg|thumb|350px|Exhibition catalogue, 1968, [http://monoskop.org/log/?p=388 Log], [[Media:Reichardt_Jasia_ed_Cybernetic_Serendipidity_The_Computer_and_the_Arts.pdf|PDF]] (b&w), [[Media:Reichardt_Jasia_ed_Cybernetic_Serendipidity_The_Computer_and_the_Arts_1969.pdf|PDF]] (hi-res color).]] |

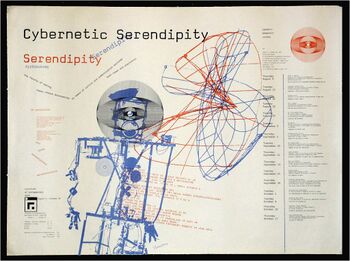

| − | [[Image:Cybernetic_Serendipity_exhibition_poster.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Cybernetic_Serendipity_exhibition_poster.jpg|thumb|350px|Exhibition poster by [[Franciszka Themerson]].]] |

'''Cybernetic Serendipity''' was an exhibition of cybernetic art curated by [[Jasia Reichardt]] and shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, [[London]], from 2 August to 20 October 1968. Later it moved to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., running there from 16 July to 31 August 1969; and finally to the recently founded Exploratorium in San Francisco, where it ran from 1 November to 18 December 1969. | '''Cybernetic Serendipity''' was an exhibition of cybernetic art curated by [[Jasia Reichardt]] and shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, [[London]], from 2 August to 20 October 1968. Later it moved to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., running there from 16 July to 31 August 1969; and finally to the recently founded Exploratorium in San Francisco, where it ran from 1 November to 18 December 1969. | ||

| − | The show featured a comprehensive assortment of pioneer techno-artists including [[Edward Ihnatowicz]], [[Liliane Lijn]], [[Gustav Metzger]], [[Nam June Paik]], [[Nicolas Schöffer]], and [[Jean Tinguely]], and as represented by a number of their more noteworthy pieces including Paik's ''Robot K-456'' (1964), Schöffer's ''CYSP-1'' (1956); and Tinguely's ''Méta-Matic'' (1961). It also included works by engineers, mathematicians, composers and poets, an impression of all of which can be gathered from a [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8TJx8n9UsA 1968 video narrated by Jasia Reichardt]. Reichardt also went on to serve as the editor of a book, ''Cybernetics, Art and Ideas'' (1971), extending this study of the relationship between cybernetics and arts. | + | The show featured a comprehensive assortment of pioneer techno-artists including [[Edward Ihnatowicz]], [[Liliane Lijn]], [[Gustav Metzger]], [[Nam June Paik]], [[Nicolas Schöffer]], and [[Jean Tinguely]], and as represented by a number of their more noteworthy pieces including Paik's ''Robot K-456'' (1964), Schöffer's ''CYSP-1'' (1956); and Tinguely's ''Méta-Matic'' (1961). It also included works by engineers, mathematicians, composers and poets, an impression of all of which can be gathered from a [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8TJx8n9UsA 1968 video narrated by Jasia Reichardt]. Reichardt also went on to serve as the editor of a book, ''[[Reichardt#Reichardt1971|Cybernetics, Art and Ideas]]'' (1971), extending this study of the relationship between cybernetics and arts. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Press release (1968)== | ||

| − | |||

<blockquote>«Cybernetics - derives from the Greek «kybernetes» meaning «steersman»; our word «governor» comes from the Latin version of the same word. The term cybernetics was first used by Norbert Wiener around 1948. In 1948 his book «Cybernetics» was subtitled «communication and control in animal and machine.» The term today refers to systems of communication and control in complex electronic devices like computers, which have very definite similarities with the processes of communication and control in the human nervous system. A cybernetic device responds to stimulus from outside and in turn affects external environment, like a thermostat which responds to the coldness of a room by switching on the heating and thereby altering the temperature. This process is called feedback. Exhibits in the show are either produced with a cybernetic device (computer) or are cybernetic devices in themselves. They react to something in the environment, either human or machine, and in response produce either sound, light or movement. Serendipity – was coined by Horace Walpole in 1754. There was a legend about three princes of Serendip (old name for Ceylon) who used to travel throughout the world and whatever was their aim or whatever they looked for, they always found something very much better. Walpole used the term serendipity to describe the faculty of making happy chance discoveries. Through the use of cybernetic devides to make graphics, film and poems, as well as other randomising machines which interactc with the spectator, many happy discoveries were made. Hence the title of this show.» <br> | <blockquote>«Cybernetics - derives from the Greek «kybernetes» meaning «steersman»; our word «governor» comes from the Latin version of the same word. The term cybernetics was first used by Norbert Wiener around 1948. In 1948 his book «Cybernetics» was subtitled «communication and control in animal and machine.» The term today refers to systems of communication and control in complex electronic devices like computers, which have very definite similarities with the processes of communication and control in the human nervous system. A cybernetic device responds to stimulus from outside and in turn affects external environment, like a thermostat which responds to the coldness of a room by switching on the heating and thereby altering the temperature. This process is called feedback. Exhibits in the show are either produced with a cybernetic device (computer) or are cybernetic devices in themselves. They react to something in the environment, either human or machine, and in response produce either sound, light or movement. Serendipity – was coined by Horace Walpole in 1754. There was a legend about three princes of Serendip (old name for Ceylon) who used to travel throughout the world and whatever was their aim or whatever they looked for, they always found something very much better. Walpole used the term serendipity to describe the faculty of making happy chance discoveries. Through the use of cybernetic devides to make graphics, film and poems, as well as other randomising machines which interactc with the spectator, many happy discoveries were made. Hence the title of this show.» <br> | ||

London, 1968</blockquote> | London, 1968</blockquote> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 15: | ||

==Resources== | ==Resources== | ||

* [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8TJx8n9UsA Video introduction by Jasia Reichardt], 7 min. | * [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8TJx8n9UsA Video introduction by Jasia Reichardt], 7 min. | ||

| − | * [http://ubu.com/sound/cybernetic.html Cybernetic Serendipity Music], 1968. | + | * [http://ubu.com/sound/cybernetic.html Cybernetic Serendipity Music], 1968, [https://archive.org/details/cybernetic-serendipity-music IA]. |

* [http://cyberneticserendipity.net/ Cybernetic Serendipity Archive] | * [http://cyberneticserendipity.net/ Cybernetic Serendipity Archive] | ||

| Line 20: | Line 21: | ||

* [http://monoskop.org/log/?p=388 ''Cybernetic Serendipidity. The Computer and the Arts: a Studio International Special Issue''], ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Studio International, Jul 1968; 2nd ed., rev., Sep 1968, 103 pp; repr., New York: Praeger, 1969, 101 pp; repr., London: Studio International Foundation, 2018, 101 pp. Exh. catalogue. Features a cover designed by Franciszka Themerson; an introduction by Jasia Reichardt; an overview of cybernetics and its founder, Norbert Wiener; separate sections dedicated to the connections between the computer and music, dance, poetry, painting, film, architecture, and graphics; a glossary; and a bibliography. | * [http://monoskop.org/log/?p=388 ''Cybernetic Serendipidity. The Computer and the Arts: a Studio International Special Issue''], ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Studio International, Jul 1968; 2nd ed., rev., Sep 1968, 103 pp; repr., New York: Praeger, 1969, 101 pp; repr., London: Studio International Foundation, 2018, 101 pp. Exh. catalogue. Features a cover designed by Franciszka Themerson; an introduction by Jasia Reichardt; an overview of cybernetics and its founder, Norbert Wiener; separate sections dedicated to the connections between the computer and music, dance, poetry, painting, film, architecture, and graphics; a glossary; and a bibliography. | ||

* [https://monoskop.org/log/?p=20482 ''The Magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts'' 5], ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, Aug 1968, 38 pp. With texts by Martin Gardner, Pierre Barbaud, and Charles Csuri. | * [https://monoskop.org/log/?p=20482 ''The Magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts'' 5], ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, Aug 1968, 38 pp. With texts by Martin Gardner, Pierre Barbaud, and Charles Csuri. | ||

| − | * ''The Magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts'' 6, ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, Sep 1968, 38 pp. With texts by Daphne Oram, Max Bense, Petar Milojevic, and Nam June Paik. | + | * [https://monoskop.org/log/?p=20482 ''The Magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts'' 6], ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, Sep 1968, 38 pp, [https://archive.org/details/ETC0726 IA]. With texts by Daphne Oram, Max Bense, Petar Milojevic, and Nam June Paik. |

==Literature== | ==Literature== | ||

| + | |||

* Jonathan Benthall, [http://dada.compart-bremen.de/docUploads/Benthall_What_the_computer_saw_SI1968_220.pdf "What the computer saw"], 1968. Catalogue review. | * Jonathan Benthall, [http://dada.compart-bremen.de/docUploads/Benthall_What_the_computer_saw_SI1968_220.pdf "What the computer saw"], 1968. Catalogue review. | ||

| + | |||

* "Exhibitions: Cybernetic Serendipity", ''Time'', 4 Oct 1968. [http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,838821,00.html] | * "Exhibitions: Cybernetic Serendipity", ''Time'', 4 Oct 1968. [http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,838821,00.html] | ||

| − | * Jasia Reichardt, [https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/cybernetic-serendipity-getting-rid-of-preconceptions-jasia-reichardt "Cybernetic Serendipity'—Getting Rid of Preconceptions"], ''Studio International'' 176:905, London, Nov 1968, pp 176-177. | + | |

| + | * [[Jasia Reichardt]], [https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/cybernetic-serendipity-getting-rid-of-preconceptions-jasia-reichardt "Cybernetic Serendipity'—Getting Rid of Preconceptions"], ''Studio International'' 176:905, London, Nov 1968, pp 176-177. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Jack Burnham]], [[Media:Burnham_Jack_1980_Art_and_Technology_The_Panacea_That_Failed.pdf|"Art and Technology: The Panacea That Failed"]], in ''The Myths of Information: Technology and Postindustrial Culture'', ed. Kathleen Woodward, Madison, WI: Coda Press, 1980; repr. in ''[[Media:Hanhardt_John_ed_Video_Culture_A_Critical_Investigation.pdf|Video Culture: A Critical Investigation]]'', ed. John Hanhardt, Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1986. | ||

| + | |||

* Edward A Shanken, [http://web.archive.org/web/20050310115453/http://www.duke.edu/~giftwrap/CyberArtExc.html "Cybernetics and Art: Cultural Convergence in the 1960s"], 2000. | * Edward A Shanken, [http://web.archive.org/web/20050310115453/http://www.duke.edu/~giftwrap/CyberArtExc.html "Cybernetics and Art: Cultural Convergence in the 1960s"], 2000. | ||

| − | * Mihai Nadin, [http://web.archive.org/web/20071019034101/http://www.code.uni-wuppertal.de/uk/computational_design/who/nadin/publications/articles_in_books/aesthet.html "The Aesthetic Challenge of the Impossible"], n.d. | + | |

| + | * [[Mihai Nadin]], [http://web.archive.org/web/20071019034101/http://www.code.uni-wuppertal.de/uk/computational_design/who/nadin/publications/articles_in_books/aesthet.html "The Aesthetic Challenge of the Impossible"], n.d. | ||

| + | |||

* Brent MacGregor, [http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.87.4857&rep=rep1&type=pdf "Cybernetic Serendipity Revisited"], in ''Creativity & Cognition 2002'', 2002, pp 11-13; [http://viola.informatik.uni-bremen.de/typo/fileadmin/media/lernen/McGregor2008.pdf repr.], in ''White Heat Cold Logic'', ed. Paul Brown, et al., MIT Press, 2008. | * Brent MacGregor, [http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.87.4857&rep=rep1&type=pdf "Cybernetic Serendipity Revisited"], in ''Creativity & Cognition 2002'', 2002, pp 11-13; [http://viola.informatik.uni-bremen.de/typo/fileadmin/media/lernen/McGregor2008.pdf repr.], in ''White Heat Cold Logic'', ed. Paul Brown, et al., MIT Press, 2008. | ||

| − | * Brent MacGregor, [http://sci-hub. | + | |

| − | * Rainer Usselmann, [http://sci-hub. | + | * Brent MacGregor, [http://sci-hub.st/10.1145/581710.581713 "Cybernetic Serendipity Revisited"], in ''Proceedings of the 4th conference on Creativity & cognition'', Oct 2002. |

| − | * Jasia Reichardt, "Cybernetic Serendipity", Paraflows 06 symposium, 2005, [http://radio.sztaki.hu/node/get.php/666pr588 Programme audio, 96 kbps, mp3, 26:13] | + | |

| + | * Rainer Usselmann, [http://sci-hub.st/10.1162/002409403771048191 "The Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA London"], ''Leonardo'' 36:5, Oct 2003, pp 389-396. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Jasia Reichardt]], "Cybernetic Serendipity", Paraflows 06 symposium, 2005, [http://radio.sztaki.hu/node/get.php/666pr588 Programme audio, 96 kbps, mp3, 26:13] | ||

| + | |||

* Regine, [http://www.we-make-money-not-art.com/archives/2006/07/-via-autonomous.php "Cybernetic Serendipity"], ''we-make-money-not-art'', Jul 2006. | * Regine, [http://www.we-make-money-not-art.com/archives/2006/07/-via-autonomous.php "Cybernetic Serendipity"], ''we-make-money-not-art'', Jul 2006. | ||

| − | * María Fernández, [http://sci-hub. | + | |

| + | * María Fernández, [http://sci-hub.st/10.1080/00043249.2008.10791311 "Detached from HiStory: Jasia Reichardt and ''Cybernetic Serendipity''"], ''Art Journal'' 67:3, Fall 2008, pp 6-23. | ||

| + | |||

* Catherine Mason, [http://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/cybernetic-serendipity-history-and-lasting-legacy "Cybernetic Serendipity: History and Lasting Legacy"], ''Studio International'', 11 Mar 2018. | * Catherine Mason, [http://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/cybernetic-serendipity-history-and-lasting-legacy "Cybernetic Serendipity: History and Lasting Legacy"], ''Studio International'', 11 Mar 2018. | ||

| Line 49: | Line 64: | ||

{{Avant-garde art exhibitions and events}} | {{Avant-garde art exhibitions and events}} | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Series:Computer art]] |

Latest revision as of 23:36, 27 January 2023

Cybernetic Serendipity was an exhibition of cybernetic art curated by Jasia Reichardt and shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, from 2 August to 20 October 1968. Later it moved to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., running there from 16 July to 31 August 1969; and finally to the recently founded Exploratorium in San Francisco, where it ran from 1 November to 18 December 1969.

The show featured a comprehensive assortment of pioneer techno-artists including Edward Ihnatowicz, Liliane Lijn, Gustav Metzger, Nam June Paik, Nicolas Schöffer, and Jean Tinguely, and as represented by a number of their more noteworthy pieces including Paik's Robot K-456 (1964), Schöffer's CYSP-1 (1956); and Tinguely's Méta-Matic (1961). It also included works by engineers, mathematicians, composers and poets, an impression of all of which can be gathered from a 1968 video narrated by Jasia Reichardt. Reichardt also went on to serve as the editor of a book, Cybernetics, Art and Ideas (1971), extending this study of the relationship between cybernetics and arts.

Contents

Press release (1968)[edit]

«Cybernetics - derives from the Greek «kybernetes» meaning «steersman»; our word «governor» comes from the Latin version of the same word. The term cybernetics was first used by Norbert Wiener around 1948. In 1948 his book «Cybernetics» was subtitled «communication and control in animal and machine.» The term today refers to systems of communication and control in complex electronic devices like computers, which have very definite similarities with the processes of communication and control in the human nervous system. A cybernetic device responds to stimulus from outside and in turn affects external environment, like a thermostat which responds to the coldness of a room by switching on the heating and thereby altering the temperature. This process is called feedback. Exhibits in the show are either produced with a cybernetic device (computer) or are cybernetic devices in themselves. They react to something in the environment, either human or machine, and in response produce either sound, light or movement. Serendipity – was coined by Horace Walpole in 1754. There was a legend about three princes of Serendip (old name for Ceylon) who used to travel throughout the world and whatever was their aim or whatever they looked for, they always found something very much better. Walpole used the term serendipity to describe the faculty of making happy chance discoveries. Through the use of cybernetic devides to make graphics, film and poems, as well as other randomising machines which interactc with the spectator, many happy discoveries were made. Hence the title of this show.»

London, 1968

Statement by the curator (2005)[edit]

«One of the journals dealing with the Computer and the Arts in the mid-sixties, was Computers and the Humanities. In September 1967, Leslie Mezei of the University of Toronto, opened his article on «Computers and the Visual Arts» in the September issue, as follows: «Although there is much interest in applying the computer to various areas of the visual arts, few real accomplishments have been recorded so far. Two of the causes for this lack of progress are technical difficulty of processing two-dimensional images and the complexity and expense of the equipment and the software. Still the current explosive growth in computer graphics and automatic picture processing technology are likely to have dramatic effects in this area in the next few years.» The development of picture processing technology took longer than Mezei had anticipated, partly because both the hardware and the software continued to be expensive. He also pointed out that most of the pictures in existence in 1967 were produced mainly as a hobby and he discussed the work of A. Michael Noll, Charles Csuri, Jack Citron, Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, and H.P. Paterson. All these names are familiar to us today as the pioneers of computer art history. Mezei himself too was a computer artist and produced series of images using maple leaf design and other national Canadian themes. Most of the computer art in 1967 was made with mechanical computer plotters, on CRT displays with a light pen or from scanned photographs. Mathematical equations that produced curves, lines or dots, and techniques to introduce randomness, all played their part in those early pictures. Art made with these techniques was instantaneously recognisable as having been produced either by mechanical means or with a program. It didn't actually look as if it had been done by hand. Then, and even now, most art made with the computer carries an indelible computer signature. The possibility of computer poetry and art was first mentioned in 1949. By the beginning of the 1950s it was a topic of conversation at universities and scientific establishments, and by the time computer graphics arrived on the scene, the artists were scientists, engineers, architects. Computer graphics were exhibited for the first time in 1965 in Germany and in America. 1965 was also the year when plans were laid for a show that later came to be called «Cybernetic Serendipity,» and presented at the ICA in London in 1968. It was the first exhibition to attempt to demonstrate all aspects of computer-aided creative activity: art, music, poetry, dance, sculpture, animation. The principal idea was to examine the role of cybernetics in contemporary arts. The exhibition included robots, poetry, music and painting machines, as well as all sorts of works where chance was an important ingredient. It was an intellectual exercise that became a spectacular exhibition in the summer of 1968.

Jasia Reichardt, London, 2005

Resources[edit]

- Video introduction by Jasia Reichardt, 7 min.

- Cybernetic Serendipity Music, 1968, IA.

- Cybernetic Serendipity Archive

Publications[edit]

- Cybernetic Serendipidity. The Computer and the Arts: a Studio International Special Issue, ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Studio International, Jul 1968; 2nd ed., rev., Sep 1968, 103 pp; repr., New York: Praeger, 1969, 101 pp; repr., London: Studio International Foundation, 2018, 101 pp. Exh. catalogue. Features a cover designed by Franciszka Themerson; an introduction by Jasia Reichardt; an overview of cybernetics and its founder, Norbert Wiener; separate sections dedicated to the connections between the computer and music, dance, poetry, painting, film, architecture, and graphics; a glossary; and a bibliography.

- The Magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts 5, ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, Aug 1968, 38 pp. With texts by Martin Gardner, Pierre Barbaud, and Charles Csuri.

- The Magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts 6, ed. Jasia Reichardt, London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, Sep 1968, 38 pp, IA. With texts by Daphne Oram, Max Bense, Petar Milojevic, and Nam June Paik.

Literature[edit]

- Jonathan Benthall, "What the computer saw", 1968. Catalogue review.

- "Exhibitions: Cybernetic Serendipity", Time, 4 Oct 1968. [1]

- Jasia Reichardt, "Cybernetic Serendipity'—Getting Rid of Preconceptions", Studio International 176:905, London, Nov 1968, pp 176-177.

- Jack Burnham, "Art and Technology: The Panacea That Failed", in The Myths of Information: Technology and Postindustrial Culture, ed. Kathleen Woodward, Madison, WI: Coda Press, 1980; repr. in Video Culture: A Critical Investigation, ed. John Hanhardt, Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1986.

- Edward A Shanken, "Cybernetics and Art: Cultural Convergence in the 1960s", 2000.

- Brent MacGregor, "Cybernetic Serendipity Revisited", in Creativity & Cognition 2002, 2002, pp 11-13; repr., in White Heat Cold Logic, ed. Paul Brown, et al., MIT Press, 2008.

- Brent MacGregor, "Cybernetic Serendipity Revisited", in Proceedings of the 4th conference on Creativity & cognition, Oct 2002.

- Rainer Usselmann, "The Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA London", Leonardo 36:5, Oct 2003, pp 389-396.

- Jasia Reichardt, "Cybernetic Serendipity", Paraflows 06 symposium, 2005, Programme audio, 96 kbps, mp3, 26:13

- Regine, "Cybernetic Serendipity", we-make-money-not-art, Jul 2006.

- María Fernández, "Detached from HiStory: Jasia Reichardt and Cybernetic Serendipity", Art Journal 67:3, Fall 2008, pp 6-23.

- Catherine Mason, "Cybernetic Serendipity: History and Lasting Legacy", Studio International, 11 Mar 2018.

See also[edit]

Links[edit]

- Serendipity Symposium 2017 of the Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence and Simulation of Behaviour (AISB), St Mary’s University, London, 15 Jun 2017.

- 50th Anniversary, Creativity and Collaboration: Revisiting Cybernetic Serendipity colloquium, Washington, D.C., 13-14 Mar 2018. Videos and report.

- Resource by Yuri Pattison

- Cybernetic Serendipity on MediaArtNet

- Cybernetic Serendipity on compArt daDA

- Wikipedia

| Art exhibitions and events | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Second Spring Exhibition of OBMOKhU (Moscow, 1920-21), Congress of International Progressive Artists (Düsseldorf, 1922), Congress of the Constructivists and Dadaists (Weimar, 1922), First Russian Art Exhibition (Berlin, 1922), New Art Exhibition (Vilnius, 1923), Zenit Exhibition (Belgrade, 1924), Contimporanul Exhibition (Bucharest, 1924), Machine-Age Exposition (New York, 1927), a.r. International Collection of Modern Art (Łódź, 1931), New Tendencies (Zagreb, 1961-73), The Responsive Eye (New York, 1965), 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering (New York, 1966), Cybernetic Serendipity (London, 1968), Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form (Bern, 1969), Information (New York, 1970), Software - Information Technology: Its New Meaning for Art (New York, 1970), Documenta 5 (Kassel, 1972), Pictures (New York, 1977), Biennial of Dissent (Venice, 1977), Les Immatériaux (Paris, 1985), Magiciens de la Terre (Paris, 1989), Hybrid Workspace (Kassel, 1997) | ||