Difference between revisions of "Lettrism"

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

===Anthologies=== | ===Anthologies=== | ||

* Jean-Paul Curtay, ''[https://monoskop.org/log/?p=20524 La poésie lettriste]'', Paris: Seghers, 1974, 380 pp. The first anthology of Lettrist poetry, also includes a historical essay by Curtay and a selection of Lettrist documents. {{fr}} | * Jean-Paul Curtay, ''[https://monoskop.org/log/?p=20524 La poésie lettriste]'', Paris: Seghers, 1974, 380 pp. The first anthology of Lettrist poetry, also includes a historical essay by Curtay and a selection of Lettrist documents. {{fr}} | ||

| + | * [[Media:Selected_Theoretical_Texts_from_Letterists_1983.pdf|"Selected Theoretical Texts from Letterists"]], ed. & trans. David W. Seaman, ''Visible Language'' 17:3, Jul 1983, pp 70-83. [http://visiblelanguagejournal.com/issue/67] {{en}} | ||

==Literature== | ==Literature== | ||

Revision as of 08:14, 28 August 2020

The Lettrism [or Letterism], founded in 1946 by Isidore Isou and Gabriel Pomerand, uses letters as "sounds" and then as "images". Poetry turns into music and writing becomes painting. The letterists extend these changing relationships to film, culture and society. In 1952 the movement divides because of diverging objectives: living art or the art of living. Jean-Louis Brau, Guy Debord and Gil Wolman founded the Lettrist International to "transcend art". Marc’O set up the group "Externalists" to encourage the uprising of youth. The Isouists asserted that their only doctrine came from a single creator. (Source)

Contents

Historical note

This section is based on a leaflet issued by Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid.

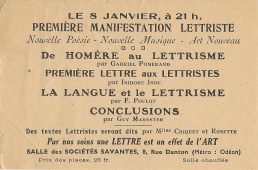

The Letter as Sound 1946-49

Lettrism takes its name from the letter that some young people, of the inter-war generation, wanted to use in ways other than words, which they believed had been killed by propaganda. The term is launched on January 8, 1946, in Paris, at the movement’s first manifestation, in the Salle des Sociétés Savantes. Gabriel Pomerand, Isidore Isou, Georges Poulot and Guy Marester announced a new poetic revolution: to make a poetry of letters, to realize “an international of direct communication” and to “make poetry out of everything.” Their collective manifesto was published in June of 1946 in the first issue of La Dictature lettriste. At the end of 1946, after hearing Pomerand speak, François Dufrêne said: “Poetry is a shout,” and joined the group. During the third manifestation, on April 3, 1947, Pomerand directed Octuor en K. On April 24, 1947 Gallimard published Introduction à une nouvelle poésie et une nouvelle musique by Isou. On June 20, 1947, at the lecture Après nous le lettrisme [After Us, Lettrism], the Dadaists asserted their paternity. On October 17, 1947, the autobiography that Isou had written in Paris was published: Agrégation d’un nom et d’un messie.

Between 1947 and 1949, while the Dadaists continued to claim precedence, Isou and Pomerand multiplied publications, lectures and scandals: Isou’s books, theoretical ones such as Une nouvelle poésie et une nouvelle musique, apologetical ones such as Agrégation d’un nom et d’un messie and attempted alliances such as Réflexions sur André Breton; group lectures on youth uprising, which Isou would develop in Traité d’économie nucléaire; lectures by Pomerand on prostitution, pederasty, rain and fine weather, that he published and had him sent to jail, such as his book Lettres ouvertes à un mythe. Le cri et son archange, which Isou wanted to appropriate, led Pomerand to break with him. Isou published Isou ou la Mécanique des femmes, which brought him legal troubles, like those of Pomerand.

1949 and the beginning of 1950 marked a move to the production of films and paintings. The documentary filmed about Saint Germain des Près, on which Jacques Baratier worked with Pomerand starting in 1947, was finished in 1949. This film interweaves different shots of Saint Germain with films extracts and symbolic scenes: Pomerand destroying a piano, burning a work by Picasso, shattering a stained glass window and shouting a poem. Titled Paris ton décor fout le camp [Paris, Your Decor is Flying the Coop] by Pomerand, and later Désordre [Disorder] by Baratier, was censured by the distributor, which replaced Pomerand’s commentary. In the middle of 1949, lettrism moved from the field of poetics to the field of plastic art, with the arrival of Gil Wolman and Brau who produced abstract writings, and with the arrival of Maurice Lemaître, who was very active with the publication of a sole issue of Front de la Jeunesse and in the first issue of Ur.

The Letter as Image 1950-52

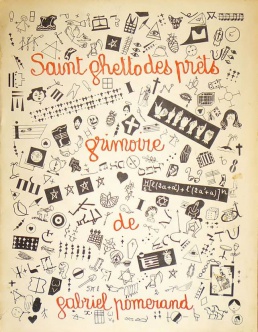

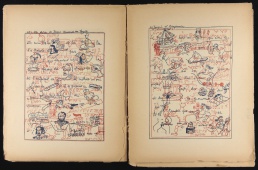

Through a combination of secret alphabets, drawings and rebus in metagraphy, Pomerand drew Saint ghetto des prêts [Saint Ghetto of the Loans], his commentary that had been censured. It appeared in 1950. That same year, Isou published Les Journaux des Dieux [Diaries of the Gods], an essay in which literature and painting merge, and which is illustrated with a metagraphy. At the end of 1950, Lemaître published the review Ur containing his metagraphic collages, theoretical texts by Claude Matricon in collaboration with Brau about the death of aesthetics and in collaboration with Wolman on the death of art, as well as texts by Isou on metagraphy.

In April of 1951 the diffusion of the unfinished film by Isou, Traité de Bave et d’éternité [Treaty on Venom and Eternity], attracted Guy Debord. In May of 1951, Pomerand showed his film La légende cruelle [The Cruel Legend], which disintegrates paintings by Léonor Fini. After Lemaître’s film, at the end of 1951, Le film est déjà commencé? [Has the Film Started Yet?], all the lettrist films of 1952 exhausted all possibilities offered by images: the single image in Wolman’s L’anticoncept [The Anticoncept], B/W sequences in Debord’s Hurlements en faveur de Sade [Howls for Sade], transparent images in Brau’s La Barque de la vie courante [The Boat of Current Life] and imaginary images in Dufrêne’s Tambours du jugement premier [Drums of the First Judgment], a movie devoid of film. They published their scripts and theories in the only number of the review Ion.

In 1951, five years after the reading of a manifesto by Jean Caillens on lettrist painting, Pomerand transferred the principles of Saint Ghetto des Prêts to approximately forty pictographic and metagraphic paintings, and twenty of 1952, such as Le Prisonnier [The Prisoner]. Some were published in June of 1952. On October 31, 1952 Isou had an exhibit of a series of 36 paintings, Les Nombres [The Numbers], which are a rebus representation of traditional form poems. He would also paint the coded text of his Introduction à la Métagraphologie, entitled Amos, on nine black and white photographs.

Lettrism, Art or Weapon? June-December 1952

Due to diverging objectives, the lettrists splintered into different groups.

The Externalists, whose name reflected the situation of youth “out” of the market, positioned themselves between reform and revolution. In June of 1952, the journal Soulèvement de la jeunesse, by Yolande du Luart and Marc’O, supporter of the future president of the Council, diffused political and artistic lettrist ideas. It shows Pomerand’s first paintings of 1951 and the 1952 paintings by Marc’O, du Luart and Poucette, who showed her lettrist paintings on December 10, accompanied by a lettrist sound system by François Dufrêne. This journal published the first text by Yves Klein. Jacques Spacagna became part of the group. Their externalist trade union had a short life.

The Lettrist International, founded in June of 1952 by Berna, Brau, Debord and Wolman, painted on a Parisian wall: Never work. On October 20, 1952, to denounce the spectacular promotion of the Chaplin film Limelight, they distributed a pamphlet entitled Finis les pieds plats [No More Flat Feet]. Disavowed by Isou, they responded that “the most urgent exercise of freedom is the destruction of idols” and they distanced themselves from Isou, who did the same to them. The conflict became public in the first issue of their review Internationale Lettriste. On Decembre 7, 1952, at the Aubervilliers Conference, Brau wrote their principles: “It is not to be greater than Picasso, but to have a life as exciting as Picasso, so far as Picasso had an exciting life”, and “It’s in transcending art that the approach still needs to be done.” The first Directive of the Situationist International would increase the revolutionary objective.

The Isouists convinced themselves that they would discover the laws of evolution and economic means, if they could go deep enough into their initial ideas. Lemaître wrote “A million arts can be created” (Ur no. 2) and “Sistème de Notasion pour les Lètries,” outcome-less. Later Isou would publish his generalizations, extended to immaterial. The group would return to plastic activities starting in 1961, with a second generation, post-war born, focused on the art market. All of them rewrote history, preserving the name “Lettrists”

Protagonists

Publications

Periodicals

- Ur. Cahiers pour un dictat culturel, 3+7 numbers, ed. Maurice Bismuth, Paris: Brunidor, 1950-53 (nos. 1-3) & 1963-67 (nos. 1-7). [1] [2]

- Ion. Centre de création, 1 issue, ed. Marc-Gilbert Guillaumain [Marc’O], Apr 1952, 286 pp. [3] [4]

Writings

See the respective pages of protagonists.

Anthologies

- Jean-Paul Curtay, La poésie lettriste, Paris: Seghers, 1974, 380 pp. The first anthology of Lettrist poetry, also includes a historical essay by Curtay and a selection of Lettrist documents. (French)

- "Selected Theoretical Texts from Letterists", ed. & trans. David W. Seaman, Visible Language 17:3, Jul 1983, pp 70-83. [5] (English)

Literature

- Jean-Paul Curtay, Lettrisme et hypergraphie. Gérard-Philippe Broutin, Jean-Paul Curtay, Jean-Pierre Gillard, François Poyet, Paris: Georges Fall, 1972. (French)

- Mirella Bandini, "Intorno ad un saggio di Isidore Isou: De l'impressionisme au lettrisme", Data, Autumn 1974, pp 83-87. (Italian),(English)

- Pietro Ferrua (ed.), Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Letterism, Paris & Portland, Oregon: Avant-Garde, 1979, 164 pp. (English)

- Visible Language 17(3): "Letterisme: A Point of View", ed. Stephen C. Foster, Jul 1983. [6] (English)

- Jean-Paul Curtay, Letterism and Hypergraphics: The Unknown Avant-Garde, 1945—1985, forew. Martha Wilson, New York: Franklin Furnace, 1985, [78] pp. Catalogue. (English)

- Stewart Home, "The Lettriste Movement", ch 2 in Home, The Assault on Culture: Utopian Currents from Lettrisme to Class War, London: Aporia Press and Unpopular Books, 1988; 2nd ed., AK Press, 1991. (English)

- Frédérique Devaux, Le cinéma lettriste, 1951-1991, Paris: Paris expérimental, 1992. (French)

- Roland Sabatier, Le Lettrisme: les créations et les créateurs, Z’Editions, 1999. (French)

- Sylvain Monsegu, "Lettrism", in Art Tribes, ed. Achille Bonito Oliva, Milan: Skira, 2002, pp 35-84. (English)

- Mirella Bandini, Pour une histoire du lettrisme, trans. Anne-Catherine Caron, Paris: Jean-Paul Rocher, 2003, 112 pp. (French)

- Per una storia del lettrismo, Gavorrano: TraccEdizioni, 2005, 123 pp. (Italian)

- Figures de la négation: avant-gardes du dépassement de l'art, ed. Yan Ciret, Saint-Étienne: Musée d'art moderne, 2004, 178 pp. TOC. Catalogue for exh. held 22 Nov 2003-22 Feb 2004. (French)

- Próximamente en esta pantalla: el cine letrista, entre la discrepancia y la sublevación, eds. Eugeni Bonet and Eduard Escoffet, Barcelona: MACBA, 2005. (Spanish)

- Bernard Girard, Paris, laboratoire des avant-gardes, 1945-1965, Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2008. Review: Pageard (Critique d'art). (French)

- Lenka Holubová Mikolášová, Lettrismus - akademická avantgarda, Prague: Univerzita Karlova, 2009. PhD dissertation. (Czech)

- Lettrisme: vue d’ensemble sur quelques dépassements précis, La Seyne-sur-Mer: Villa Tamaris, 2010, 264 pp. Catalogue. Review: Froger (Critique d'art). [7] [8] (French)

- Guillaume Robin, Lettrisme, le bouleversement des arts: essai sur le lettrisme et les différents mouvements artistiques, Paris: Hermann, 2010, 174 pp. Reviews: Froger (Critique d'art), Juillerat (La Critique), Blay (Kritikon Litterarum). [9] (French)

- Frédéric Acquaviva, "Wolman in the Open", in Gil J Wolman. I Am Immortal and Alive, ed. Clara Plasencia, Barcelona: MACBA, 2010, pp 10-43. [10] (English)

- "Wolman, al descobert", in Gil J Wolman. Sóc immortal i estic viu, Barcelona: MACBA, 2010, pp 10-43. [11] (Catalan)

- "Wolman, al descubierto", in Gil J Wolman. Sóc immortal i estic viu, Barcelona: MACBA, 2010, pp 146-166. [12] (Spanish)

- Fabrice Flahutez, Le lettrisme historique était une avant-garde, Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2011, 256 pp. [13] (French)

- Andrew V. Uroskie, "Beyond the Black Box: The Lettrist Cinema of Disjunction", October 135, MIT Press, Winter 2011, pp 21-48. (English)

- Hannah Feldman, "Sonic Youth, Sonic Space: Isidore Isou and the Lettrist Acoustics of Deterritorialization", ch 3 in Feldman, From a Nation Torn: Decolonizing Art and Representation in France, 1945-1962, Duke University Press, 2014, pp 77-108, n237-244.

- Kaira M. Cabañas, Off-Screen Cinema: Isidore Isou and the Lettrist Avant-Garde, University of Chicago Press, 2014. (English)

Resources

- Letterist works on UbuWeb

- Lelettrisme.com (archive.org) (French)

- Lettriste – Situationniste – 1e Partie "Savoir vivre": 1946–1963, by François Letaillieur (French)

- Centro Studi Lettristi (Italian)

- Lettrism in Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library (English)

- http://g-r-a-l.tumblr.com/

See also

Links

- Invisible Republic: Music, Lettrism, Avant-Gardes. International Conference on Music, Avant-Gardes and Counterculture, Center for English Studies, University of Lisbon, 25-27 Oct 2017.

| Visual art | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Movements – 1990s – East Central Europe – Writers – Historians – Care – Museums – References. | ||