Zdeněk Pešánek

Zdeněk Pešánek and Jöna Pešánková in their studio with Mother with a Child, 1927.[1] | |

| Born |

June 12, 1896 Kutná Hora, Austria-Hungary (today Czech Republic) |

|---|---|

| Died |

November 21, 1965 (aged 69) Poustevny u Rumburka, Czechoslovakia |

A light-kinetic artist, painter, sculptor and architect. Zdeněk Pešánek belongs to the pioneers of abstract art, who had been creating light-kinetic works already in the 1920s. He also introduced a neon tube into the artistic context.

Life and work[edit]

Early years[edit]

Zdeněk Antonín Pešánek was born in 1896 in Kutná Hora to Karl Pešánek, a tax collector, and Marie Pešánková, a milliner. His mother came from a family of organ-builders and young Zdeněk used to spend his time in the organ workshop of his grandfather, Antonín Mölzer (1839–1916)[4].[4][5] Organ-building brings together the domains of music, carving, sculpting as well as the medium of electricity, and Pešánek later wrote that here he developed his "relation to the mechanism of apparatus".[6]

Studies[edit]

Pešánek studied at the school of sculpture and masonry in Hořice (Jičín) with Prof. Quido Tomáš Kocián (1914–17), sculpture and medal-making at the Academy of Fine Arts with Jan Štursa (1918–23), and architecture privately with Jan Kotěra. He came into contact with Devětsil group in c1922, befriending Jaromír Krejcar, Josef Chochola, Adolf Hoffmeister, Alois Wachsman, and most closely Artuš Černík.[7][8]

During his studies he found strong inspiration in the exhibitions of the futurists (1920–21), Tvrdošíjní group, and Alexandr Archipenko (1923). The years 1924–25 saw a breakthrough in his work. He entered Devětsil association and the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (both 1924), created a cycle of reliefs for the Post and Telegraphy Office in Brno (1924–25), Pomník letcům [Aviation Monument] in Prague (1925–26)[9], and began working on his Spectrophone.[10][11]

- Selected works

Working on the Transportation relief, 1925.[12]

Industry, from the relief series for Post and Telegraphy Office, Brno, 1924–25.[13]

Industry, model. From the relief series for Post and Telegraphy Office, Brno, 1924–25.[14]

Transportation, from the relief series for Post and Telegraphy Office, Brno, 1924–25.[15]

Architecture, from the relief series for Post and Telegraphy Office, Brno, 1924–25.[16]

New Society (Craddle), from the relief series for Post and Telegraphy Office, Brno, 1924–25.[17]

Smetana monument proposal, 1925.[18]

Aviation Monument, model, 1925.[19]

Spectrophone (1924–30)[edit]

In it, he bridged his pre-school interests with the leading Devětsil's theorist Karel Teige's proclaimed idea of "the mechanical kinetic and optophonetic image". Teige's call echoed the then prevailing considerations of time-based art such as the abstract cinema represented by the likes of Viktor Eggeling, although Pešánek took the concept of kinetic art elsewhere. In 1924–26 he constructed a colour piano, the first version of what he called Spectrophone (built most probably at his house in Kutná Hora[22]). The instrument projected visual kinetics onto a relief object. Originally he did not plan to include sound element, but soon, in the early 1926, he connected its light keyboard to a four-octave music keyboard. His interest in connecting visual kinetics with music did not originate in his own synaesthetic experiences, as was the case of Miroslav Ponc, but in the influence of Gustav Fechner's psychophysics. Pešánek assumed it will be possible to normalise the color scale so that he can connect it to the scale of musical tones, ie. to develop common interface to control both visuals and music. The premiere of the instrument was held on 8 April 1926 privately at his studio, with a performance of Mr. Heřman. Consequently, Pešánek received an invitation from Lessing-Hochschule for a public presentation of his instrument in Berlin, and established contact with the Petrof piano company in Hradec Králové to construct a new version.[23]

The second Spectrophone had three color registers (red, green, blue); each key could light up any color; control of the shapes of color fields was introduced; and a round-shaped projection required three meters in diameter. Construction took longer than expected, and the second version, built by Petrof's engineer Alois Zakl based on Pešánek's drawings, had instead its premiere on 13 April 1928 at the Municipal House [Obecní dům] in Prague, with Erwin Schulhoff playing compositions by A.N. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Sonata No. 9, Poem, Nocturnal, Vers la flamme and Sonata No. 10. The performance was criticised by Albert Wellek, among others, for its "naive error of inductivism or empiricism, that views the whole as a sum of the parts which can be combined among themselves.. The result is a dance of color grapes (or lampions), whose individual moments give way to often a quite charming purely impressionistic color expression." After his experiences with the three Spectrophones, Pešánek abandoned the idea of common interface to control both the music and visuals and in line with Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack's critique of earlier attempts of Louis Bertrand Castel admitted that music and visuals should be controlled separately.[24]

Third version (1928–30) returned to projection onto a relief object. Pešánek presented it at the Second Congress for Color-Tone Research [II. Kongress für Farbe-Ton-Forschung] at the University of Hamburg in October 1930, also attended by Oskar Fischinger and Hirschfeld Mack. He performed on the Spectrophone along the reproduced music of Richard Wagner's Siegfried Idyll, and delivered lecture entitled "Bildende Kunst vom Futurismus zur Farben–und Formkinetik". The reviews were positive, however after a failed attempt to initiate serial manufacturing of the Spectrophone, encouraged by positive responses from the institutes for the deaf in Prague and Brno (echoing Castel's utopia of helping the deaf to deepen their experience of music), he abandoned further work on it.[25][26]

Spectrophone, first version, 1925.[27]

Spectrophone, first version, 1925.[28]

Spectrophone, first version, 1925.[29]

Spectrophone, first version, 1925.[30]

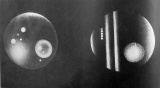

Spectrophone projection, 1928.[31]

Spectrophone projection, 1928.[32]

Spectrophone projection, 1928.[33]

Zdeněk Pešánek and Erwin Schulhoff, spring 1928.[34]

Erwin Schulhoff and Spectrophone, 1928.[35]

Invitation to the Spectrophone performance in Prague, April 1928.[36]

"Edisonka" (1926–30) and collaboration with Prague's Electric Company[edit]

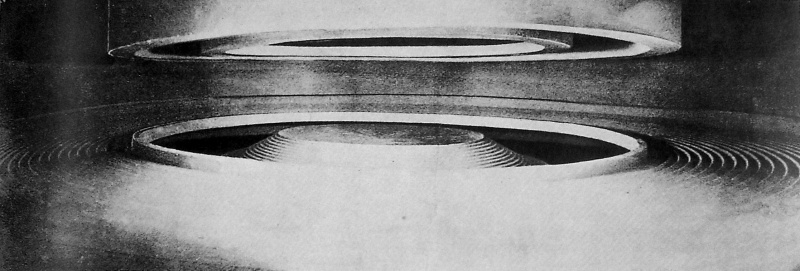

His light-kinetic sculpture for the Edison transformer station at Jeruzalémská street in Prague remains, along with László Moholy-Nagy's Light-Space Modulator (1922–30), a fundamental work of light-kinetic sculpture of the century. The sculpture can be considered an automatised version of (soundless version of) Spectrophone; it counted 420 colour bulbs (seven rows of white, yellow, green, blue, violet, red, and orange, 15 bulbs each, in each of four parts) and produced pre-programmed light-kinetic "shows" regularly from 7 to 8 PM. "Edisonka" was portrayed by Otakar Vávra and František Pilát in the short film Světlo proniká tmou [The Light Penetrates the Dark] (1931). It is hailed as the world's first public kinetic sculpture. It operated from October 1930 until 1937, and was Pešánek's first realisation in his over a decade-long collaboration with the Electric Company of the City of Prague [Elektrické podniky hlavního města Prahy]. Next to a number of light advertising works, Pešánek organised a lecture and workshop cycle O světle [About Light] (November 1931–1932) to discuss and introduce artistic considerations into context of street lighting and light advertising.[39][40]

Edisonka, 1929–30.[41]

"Edisonka", 1929–30.[42]

"Edisonka", 1929–30.[43]

"Edisonka", 1929–30.[44]

Mounting the sculpture, April 1930.[45]

Mounting the sculpture, April 1930.[46]

"Edisonka", model, 1929–30.[47]

"Edisonka", model, 1929–30.[48]

"Light workshops" advertisement, early 1930s.[49]

Světlo proniká tmou (The Light Penetrates the Dark, 1931),

dir. Otakar Vávra and František Pilát, 35mm, 4 min, 1931. Download (WEBM)

Teaching, UMPRUM[edit]

Pešánek furthered his educational efforts in establishing collaboration with Prague's Museum of Decorative Arts [Uměleckoprůmyslové museum] in 1936. The museum held his first solo exhibition (24 October–15 November 1936), and in 1939 he installed there permanent exhibition Krásné světlo [Beautiful Light] with an extensive section of his light-kinetic works (including spectrophones and reflection games; the exhibition was demolished during the Nazi occupation in 1942). He also worked with the magazine Výtvarná výchova and the School of Arts and Crafts in Bratislava. Its former director, Josef Vydra, edited Pešánek's book Kinetismus (1941) which was prepared as a practical guide for light-kinetic art.[50]

Sto let elektřiny (One Hundred Years of Electricity, 1932–36)[edit]

Being commissioned by the Electric Company of the City of Prague to decorate their new building of Zenger's Edison transformer station in Prague-Klárov, Pešánek created a series of four light-kinetic sculptures. They celebrated inventions in the field of electricity, namely Ampère's Law (1936 saw one hundred years since the death of Ampère), three-phase electric motor, transformer, and the fourth represented the growing electricity consumption in Prague since the 1880s. Originally he also considered another two pieces, inspired by lightning rod and dynamo, for which he created models. Next to the rhythmised system of colour bulbs used earlier, Pešánek worked with neon light for the first time, pioneering its use in the artistic context. New to his work were also the use of molded synthetic resin (celluloid and celon) and the predominance of industrial material. The works are abstract assemblages, although they incorporate objects like a hand, magnetic needle, inductor, diagram, or isolators. He worked with Erwin Schulhoff and Alois Hába on the acoustic part composed of concrete sounds (sirens, whirling of transformers) and rhythmic music. The work was first exhibited at Pešánek's solo exhibition in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague (1936), whose positive reception paved its way to the World Exposition in Paris (1937). New York's Museum of Modern Art and Dutch company Philips Lighting expressed interest in acquiring it, but both were met with disapproval from the Electric Company. Due to unfortunate circumstances, the work was not installed on its building and after its short appearance at Krásné světlo exhibition (1939) it was left forgotten in the basement of the Zenger station.[52][53]

Electric motor principle, from the cycle One Hundred Years of Electricity, 1932.[54]

Transformer principle, from the cycle One Hundred Years of Electricity, 1932.[55]

Fontána lázeňství (Spa Fountain, 1936–37)[edit]

Next to his Sto let elektřiny [One Hundred Years of Electricity], the Czechoslovak Pavillion at the World Exhibition in Paris (1937), whose theme was "art and technology in the modern life", included another light-kinetic sculpture by Pešánek: Fontána lázeňství [Spa Fountain] (1937). In the middle of a pool, Pešánek placed one vertical and one horizontal torso made from fiberglass; a long neon bulb protruding from the upper part of each torso curving towards the lower part of the torso in awkward angles accentuated not only the exterior, but simultaneously illuminating the interior. “In addition to neon pipes in two colors, several sections of colored light bulbs ran through the work alternating with white light bulbs. The changing colored light also enriched the play of light through the water beneath the pool.” And the whole work was coordinated to light in rhythmic synchronization with music. Although the public and French press was undoubtedly captivated by such a creation, critics at home considered his work marginal and an “undignified representation” of his native country. Interestingly, Pešánek himself considered this only a study and was faintly disappointed by its completion. He wanted to include an additional set of illuminated jetting columns of water with search lights, but it was never fulfilled for reasons of space. When it was proposed to rebuild this fountain in Prague, a site was selected; however, the Nazi occupation gave halt to the realisation.[56][5]

Both Pešánek's works for the Exposition were awarded gold medals in the category "Application of technology and electricity".[57]

Spa Fountain, model, 1936.[58]

Lying torso from the Spa Fountain, 1936.[59]

Lying torso from the Spa Fountain, 1936.[1]

Torso from the Spa Fountain, 1936. [2]

Torso from the Spa Fountain, 1936.[60]

Torso from the Spa Fountain, 1936.[61]

Female torso, 1936.[62]

Male torso, 1936.[63]

Sculpture for the main entrance of the Electric Company of the City of Prague, model, 1936.[64]

Post-war years[edit]

After the war, Pešánek continued working in the fields of light-kinetic art, light advertising and architecture, and despite limitations had several of his works realised. In 1949–56, while he was restricted from the artistic use of electricity due to the dogmatic interpretation of socialist realism, he worked at Stavoprojekt company under architect Jiří Kroha. In the late 1955, he initiated the Society of Light and Light Art at the Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, and worked there from November 1956 until 1964.[66] His wife Jöna (born Eugenie Kaiserová) died in 1948; he remarried to artist Berta Weissová in 1954.[67]

Light fountain, Slavic Agricultural Exhibition, Prague, 1948.[68]

Light fountain, Slavic Agricultural Exhibition, Prague, 1948.[69]

Light fountain, Slavic Agricultural Exhibition, Prague, 1948.[70]

Score for a light-kinetic banner, Technology of Tomorrow exhibition, Prague, 1956.[71]

Score for a kinetic advertising banner for a shop window, 1956.[72]

Kinetic advertising banner for a shop window, 1956.[73]

Later years[edit]

Despite receiving several awards, he remained outside of artistic circles of his time, and after the war his work began to be again appraised only in the mid-1960s, ie. through the Acta scaenographica magazine. In 1965, he met Frank Malina during the preparations of his exhibition in Prague. Zdeněk Pešánek died in 1965, and the same year the group Syntéza [Synthesis] was founded, bringing together young artists of kinetic and op art tendencies (Vladislav Čáp, Stanislav Zippe, Stanislav Toman, Jan Slavík, Lubomír Beneš, Jan Halada).[74][75]

A number of art historians contributed to rediscovery of Pešánek's work, including Vít Čapek, Jiří Zemánek, František Šmejkal, Krisztina Passuth, Jaroslav Anděl, Alice Štefančíková, and Karel Srp.

Exhibitions[edit]

- Solo exhibitions

- Zdeněk Pešánek – Světelné plastiky, Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, 1936.

- Zdeněk Pešánek – Světelné plastiky, Charles Square Gallery, Prague, 1966.

- Zdeněk Pešánek – Světelné plastiky, Benedikt Rejt Gallery, Louny, 1969.

- Pocta Zdeňku Pešánkovi (Pavel Opočenský / Stanislav Zippe), Felix Jenewein Gallery, Kutná Hora, 1996.

- Zdeněk Pešánek 1896/1965, retrospective, National Gallery, Prague, 1996–97; Guggenheim Museum, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris. Copies of Pešánek's works were created by Federico Díaz. [6]

- Selected group exhibitions

- World Exposition, Quai d'Orsai, Paris, 1937.

- Krásné světlo [Beautiful Light], Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, 1939–42.

- Slavic Agricultural Exhibition, Prague, 1948.

- Technology of Tomorrow, National Technical Museum, Prague, 1956.

- Umění bojující, Slavic Island, Prague, 1958. Traveled to Art Gallery, Karlovy Vary, and Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava.

- Kresby a plastiky žáků Jana Štursy [Drawing and sculpture from the students of Jan Štursa], National Gallery–Belvedere, Prague, 1964.

- Electra, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1983–84.

- Jitro kouzelníků (Umění, věda, společnost na přelomu tisíciletí) [Dawn of the Magicians? (Art, Science, Society on the Turn of Milleniums)], National Gallery, Prague, 1996–97.

- Laterna magica, Paris, 2002–03. [7]

- com.bi.nacion: Science meets Art, Kampa, Prague, 2005. [8]

- The Art of Light, ZKM, Karlsruhe, 2006–7. [9]

- Rytmy + Pohyb + Světlo: Impulsy futurismu v českém umění, Pilsen and Brno, 2012–2013. [10] [11]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 39

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 275

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 14

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 7

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 274

- ↑ Pešánek 1941, p. 28

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 274-276

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 194

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 28

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 275-276

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 33

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 30

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 31

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 32

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 34

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 35

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 19

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 277

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 69

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 55

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 276

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 44-63

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 44-63

- ↑ Pešánek 1941, pp. 34-44

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 44-63

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 48

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 49

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 50

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 51

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 58

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 58

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 59

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 56

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 56

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 57

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 134-135

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 79

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. xix-xx

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 120-149

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 131

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 139

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 140

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 141

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 130

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 130

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 133

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 133

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 148

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. xx

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 172

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 148

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 165-191

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 170

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 170

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 174-191

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 184

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 178-179

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 182

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 181

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 181

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 186

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 186

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 188

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 285

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 204-231

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, pp. 287

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 209

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 209

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 209

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 212

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 213

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 213

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. xxi

- ↑ Zemánek 1999, p. 229-231

Writings[edit]

Monograph[edit]

- Kinetismus: Kinetika ve výtvarnictví – barevná hudba, intro. František Kalivoda, Prague: Česká grafická Unie, 1941, 144 pp; repr., Prague: Akademie múzických umění, 2013; new ed., Prague: Akademie múzických umění, and Kunsthalle Prague, 2022, 174 pp. Publisher. (Czech)

- Kineticism, Prague: Academy of Performing Arts, and Kunsthalle Prague, 2022, 174 pp. With texts by Tomáš Pospiszyl and Peter Weibel. Publisher. (English)

Articles[edit]

- "Chraňme starý ráz Kutné Hory", Posázavským krajem, 12:36, 8.9.1922. (Czech)

- With Josef Chochola, "Arsinoe", Časopis československých architektů, XXIV, 1925, p 10. (Czech)

- With Josef Chochola, "Heslo: Černý kruh", Časopis československých architektů, XXIV, 1925, pp 55-59. (Czech)

- "Pomník padlým letcům v Praze", Tribuna, 17.17.1926, p 3. (Czech)

- With Josef Chochola, "Petřínská komunikace (původní zpráva)", Stavba, V, 1926-27, p 105. (Czech)

- "Barevný klavír", in Technický slovník naučný, Vol. 1, ed. Teyssler and Kotyška, Prague, 1927, p 1020-1021. (Czech)

- "Letectví a výtvarník", Letectví, 7:5, 1927, pp 104-106. (Czech)

- With J.A. Hollman, "Černý terč", Stavba, VI, 1927-28, p 23. (Czech)

- "Doslov", in Světlo a výtvarné umění v díle Zdeňka a Jöny Pešánkových, Elektrické podniky hlavního města Prahy, Autumn 1930, pp 25-27. (Czech)

- "Bildende Kunst vom Futurismus zur Farben- und Formkinetik (Mit Vorfuehrung eines Farbe-Ton-Klaviers)", in: Georg Anschutz (ed.), Farbe-Ton-Forschungen, Vol. 1, Hamburg: Meissner, 1931, pp. 193-204. (German)

- "Divadlo a světlo", Národní divadlo, 9:28, 26.4.1932, p 7. (Czech)

- "Ještě k představení 'Švejka'", Rudé právo, 28.7.1933. (Czech)

- "Světlo ve výtvarném umění", Výtvarná výchova 4:3, 1937-38, pp 6-9. (Czech)

- "Výtvarný kinetismus", Výtvarná výchova 6:4, 1939-40, pp 18-23. (Czech)

- "Vyznání architektovo", Brázda, 5:17, 29.4.1942, pp 197-199. (Czech)

- "Rozprava o historismu v malířství", Brázda, 5:18, 6.5.1942, pp 210-211. (Czech)

- "Forma výstavního prostoru s ohledem na význam užití světla jako tvárného prvku", Architekt SIA, XXXXII, 1943, pp 53-54. (Czech)

- "Do 10 let vystavíme náměstí Budovatelů (rozhovor deníku Práce se Z.Pešánkem)", Práce, 26.10.1947. (Czech)

- With Jiří Kroha, "Náměstí Budovatelů a železnice v severo-východním sektoru Prahy", Architektura ČSR, VI, 1947, pp 171-181. (Czech)

- With Borek Weiss, "Ervin Schulhoff a barevný klavír", in Ervin Schulhoff - vzpomínky, studie a dokumenty, ed. Věra Stará, Prague: Knižnice hudebních rozhledů, pp 68-78.

- "O světle, světle barevném a kinetickém ve výtvarném umění", Kultura, 33, 1958, pp 5-.

- "Poznámky k estetice světelné kinetiky", Výtvarné umění, 9:5 (21 September 1959), pp 220-227. (Czech)

- "Světlo jako umění", Literární noviny, 8:40, 3.10.1959, p 9. (Czech)

- "Světlo, světlo, světlo", Československý architekt, 5:18, 1959, p 3. (Czech)

- "Kinetismus", Acta scaenographica, 5:1, 1964-65, pp 2-8. (Czech)

- "Světelně kinetická plastika", Acta scaenographica, 5:2, 1964-65, pp 21-27. (Czech)

- "Světelně kinetický objekt", Acta scaenographica, 5:5, 1964-65, pp 81-82. (Czech)

- "Světelná fontána", Acta scaenographica, 5:7, 1964-65, pp 121-122. (Czech)

- "Die lichtkinetische Plastik", in Europa, Europa, eds. Christoph Brockhaus and Ryszard Stanisławski, 1994, pp 108-109. (German)

- "Kinetismus", in Utopien und Konflikte, eds. Jiří Ševčík and Peter Weibel, 2007, pp 57-63. (German)

- "Bemerkungen zur Ästhetik der Lichtkinetik", in Utopien und Konflikte, eds. Jiří Ševčík and Peter Weibel, 2007, pp 173-177. (German)

Catalogues[edit]

- Světelné plastiky Zdeňka Pešánka, Prague: Svaz československých výtvarných umělců, 1966, 8 pp. With text by Petr Hartmann. (Czech) [12]

- Zdeněk Pešánek: Světelné plastiky, Louny: Benedikt Rejt Gallery, 1969, 12 pp. With text by Petr Hartmann. (Czech) [13]

- Pocta Zdeňku Pešánkovi (Pavel Opočenský / Stanislav Zippe), Kutná Hora: Galerie Felixe Jeneweina města Kutné Hory, 1996, 15 pp. With texts by Jiří Machalický and Aleš Rezler. (Czech)

- Zdeněk Pešánek, 1896-1965, Prague: National Gallery, 1996, 12 pp. ISBN 8070351233. With text by Jiří Zemánek. (Czech)

Literature[edit]

Monographs, catalogues[edit]

- Světlo a výtvarné umění v díle Zdeňka a Jöny Pešánkových, Prague: Elektrické podniky hlavního města Prahy, 1930, 31 pp. (Czech)

- Adolf Felix, "Umění pohybu", pp 3-7; Antonín Nový, "Světelně-kinetická plastika architekta sochaře Zd. Pešánka na Edisonově transformační stanici u kostela sv. Jindřicha", pp 7-10; Jaroslav Jíra, "O světle v ulicích v cizině a u nás", pp 10-12; Artuš Černík, "Od sochy akademické ke světelně-barevné plastice", pp 13-20; J. Kubín, "Světelná technika a sochařství", pp 21-22; Arnošt Hošek, "Hudba tvarů a barev", pp 22-25; Zdeněk Pešánek, "Doslov", pp 25-27.

- Jiří Zemánek (ed.), Zdeněk Pešánek, 1896-1965, Prague: Národni galerie, and Gema Art, 1999, 450 pp. With texts by J. Zemánek, R. Švácha, J. Anděl, M. Juříková, and V. Havránek. [14] [15] (Czech)

- Kinetismus, eds. Peter Weibel with Christelle Havranek, Prague: Kunsthalle Praha, 2022, 272 pp. Exh. catalogue. Publisher. (English)

Selected articles[edit]

- Albert Wellek, "Das Farbeklavier", Der Auftakt 8:4 (25.4.1928), pp 85-89. (German)

- Ladislav Ptáček, "Kolonka a umění", in Almanach studentské kolonie na Letné: 1920-1930, Prague, 1931, pp 153-155. (Czech)

- František Kalivoda, "Nové podněty pro optofonetickou tvorbu", Výtvarná výchova 4:2, 1937, pp 1-45. (Czech)

- František Kalivoda, "Kinetismus Zdeňka Pešánka", Acta scaenographica, 5:1, 1964-65, pp 1-2. (Czech)

- Dušan Konečný, "Zdeněk Pešánek a kinetismus v Československu", Acta scaenographica, 6:11, 1965-66, pp 210-212. (Czech)

- Petr Hartmann, "Kinetická tvorba Zdeňka Pešánka", Výtvarné umění, 16:3, 1966, pp 424-433. (Czech)

- Dušan Konečný, Kinetizmus, Bratislava: Pallas, 1970, 88 pp. ISBN 9406870. (Slovak)

- Jaromír Fiala, "On My Work with the Pioneer of Kinetic Electric Light Art, Zdeněk Pešánek (1896-1965): A Memoire", Leonardo 3 (Summer 1980), pp 182-185. [16]

- Alice Štefánčíková, "Posel světla Zdeněk Pešánek", Revolver Revue, 21, (November 1992), pp 81-127. (Czech) [17]

- Jiří Zemánek, "Kinetismus Zdeňka Pešánka a umění instalace", Výtvarné umění, 4, 1994, pp 102-116. (Czech)

- Jiří Zemánek, "Ke genezi kinetického umění v českém poetismu - Teigova idea kinografické obrazové básně a Pešánkův barevný klavír", in Orbis Fictus - nová média v současném umění, Prague, 1995, pp 21-52. (Czech)

- Jiří Zemánek, "Zdeněk Pešánek a kinetika světla v českém umění 30.-70. let", in Orbis Fictus - nová média v současném umění, Prague, 1995, pp 53-66. (Czech)

- Pavla Pečinková, "Zdeněk Pešánek a László Moholy-Nagy", Kritická příloha Revolver Revue 7, April 1997, pp 28-36. (Czech)

- Anna Chadová, "Petrof, Schulhoff, Pešánek a barevný klavír", Hudební nástroje XXXI, No. 3, Hradec Králové, 1994, pp 146–149. (Czech)

- Jiří Zemánek, "Zdeněk Pešánek a kinetika světla v českém umění 30.–70. let", in: Ludvík Hlaváček, Marta Smolíková (eds.), Orbis Fictus, Prague: Oswald, 1995, pp 53-67. (Czech)

- Mahulena Nešlehová, "Impulses of Futurism and Czech Art", in International Futurism in Arts and Literature, Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2000.

- Jiří Zemánek, "Zdeněk Pešánek", in: Lanterna magika: New technologies in Czech art of the 20th century, Prague: KANT, 2002. [18]

- Sylva Poláková, "Rezonance českého světelného kinetismu", Sešit pro umění, teorii a příbuzné zóny 24, Prague, 2018, pp 42-58. [19] (Czech)

Theses[edit]

- Ondřej Menšík, Zdeněk Pešánek: Kinetismus a světelná kinetika, Brno: Masaryk University, 2006, 77 pp. Diploma thesis. (Czech)

- Jana Matulová, Barevná hudba, Brno: Masaryk University, 2008. Bachelor thesis. (Czech)

- Kateřina Drajsajtlová, Světelný klavír v uměleckém díle Alexandera Nikolajeviče Skrjabina a Zdeňka Pešánka, 2012, 62 pp, PDF. Bachelor thesis. (Czech)

- Lucie Linhová, Zdeněk Pešánek a jeho účast na Mezinárodní výstavě v Paříži v roce 1937, Prague: Charles University, 2012. Bachelor thesis. (Czech) [20]

- Sylva Poláková, "Rezonance filmově-architektonických konvergencí v oblasti výtvarného umění a prolamování do veřejného městského prostoru", ch 4 in Poláková, Konvergence filmu a architektury. Případ Prahy, Prague: Karlova univerzita, 2015, pp 101-137. Phd dissertation. (Czech)

Links[edit]

- Wikipedia-CZ

- Pešánek on abArt database

- Transformace: Pešánek / Díaz, Kunsthalle Prague, 30 Sep 2017.