Alex Mlynárčik

| Born |

October 14, 1934 Žilina, Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia) |

|---|---|

| Collections | Art museums in Slovakia (Web umenia), Kontakt (Vienna), Nedbalka (Bratislava), Artandconcept Gallery (Prague) |

Alex Mlynárčik (1934) is a Slovak artist.

In 1951 he was caught crossing the border in Austria and imprisoned. Later he worked as painter, decorator and photographer. He studied at Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava (Prof. Milly and Prof. Matejka, 1959-65) and Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (Prof. Sychra). In 1965-67 he worked as assistant at Bratislava's Academy.

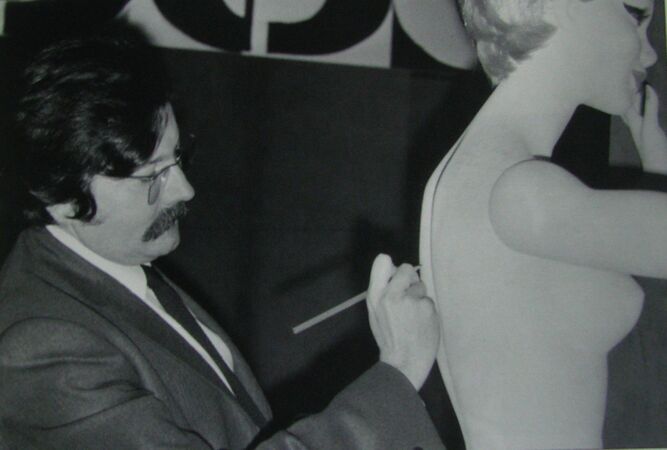

Mlynárčik began making art in the early 1960s, making unremarkable mixed-media compositions on wood. On first visiting Paris in 1964 he found an immediate affinity with Nouveau Réalisme (César, Arman, Saint Phalle, Christo), the impact of which can be seen in the development of his 'permanent manifestations' (1965 onwards), three-dimensional assemblages overlaid with public graffiti as a kind of consumer palimpsest.[1]

He realized many decorative projects for architecture, paintings, sculptures, glass works and metal works and dedicated earnings to his manifestations, interpretations, games and celebrations.[2]

In the 1970s and 1980s he lived in Prague, with regular work stays in Žilina and Paris. In 1972 he was exluded from Slovak Association of Fine Artists and considered to be a promoter of "ideas of bourgeois western art". He was granted stipend from Ford Foundation (1972) and Guggenheim Foundation (1986). In 1990-91 he was director of Arts Gallery in Žilina.

Works[edit]

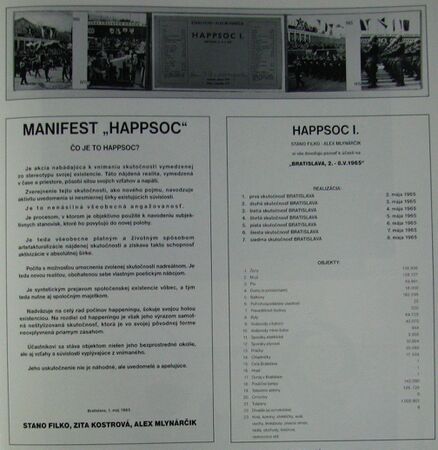

Happsoc I (1965)[edit]

Alex Mlynárčik, Stano Filko and Zita Kostrová, Happsoc I, 1965, Bratislava.

Alex Mlynárčik, Stano Filko and Zita Kostrová, Happsoc I, 1965, Bratislava.

Happsoc I, 1965/1975. Source.

The impact of Nouveau Réalisme on Mlynárčik can also be seen in Happsoc I (a neologism of ‘happenings’, ‘happy’, 'society' and 'socialism') by Mlynárčik, Stano Filko and the theorist Zita Kostrová. The trio announced a series of 'realities' to take place in Bratislava during the week of 2–9 May 1965. On 1 May, the three members wrote a manifesto explaining their planned artistic action and idea of art, which was founded upon the then current vogue for nominalism, that is, excising an experience or event from the flow of everyday life and declaring it to be a work of art. In this particular instance, it was the whole city of Bratislava and its society that was announced as an exhibition. However, the manifesto also went beyond the reductiveness of neo-Duchampian nominalism by including a parody of a national census that had taken place the previous month, listing twenty-three types of object and their number to be found in Bratislava: one castle, one Danube, 142,090 lampposts, 128,729 television aerials, six cemeteries, 138,936 females, 128,727 males, 49,991 dogs, and so on. The manifesto and data were sent to 400 people in the form of a printed invitation to Happsoc I, which designated the city of Bratislava during the week of 1–9 May as a work of art. This period was framed by two public holidays: Workers’ Day, a key event in the socialist calendar, and 9 May, which commemorated the liberation of Slovakia by the Soviet Army in 1945. It seems evident that this framing sought to draw attention to two types of participation: official parades, on the one hand, and the artists’ creation of an invisible, involuntary and imaginary participation, on the other.[3]

Happsoc II and III (1965-1966)[edit]

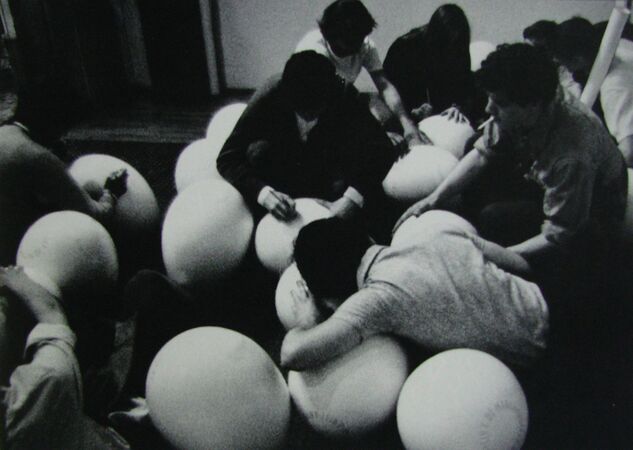

Alex Mlynárčik, Stano Filko, Happsoc II: 7 dní stvorenia [Happsoc II: The Seven Days of Creation], 1965, Bratislava.

The next Happsoc experiment was more ambitious: Happsoc II: The Seven Days of Creation [Happsoc II: 7 dní stvorenia] took place later that year (25–31.12.1965), also between two significant holidays (Christmas and the New Year); it comprised an invitation in the form of a semi-scored series of instructions for participants. Happsoc III: The Altar of Contemporaneity, by Stano Filko, went on to posit the appropriation of the entire territory of Czechoslovakia as the artist’s own work in June 1966, and the gesture is typical of his fervently megalomaniac cosmic conceptualism.[4]

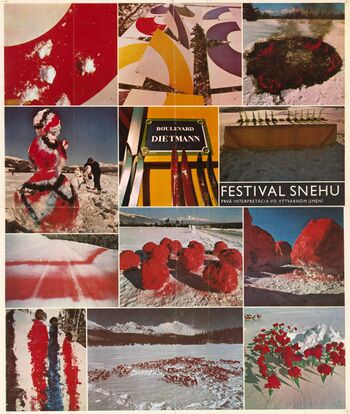

First Snow Festival (1970)[edit]

As tightly scored conceptual experiments with the social, Happsoc stands in sharp contrast to Mlynárčik’s subsequent participatory works in the later 1960s, which were more emphatically physical, visual and collective. Mlynárčik referred to these events as ‘permanent manifestations of joining art and life’.[5]

One of his most striking works of this period is the collaboratively authored First Snow Festival (1970), with the artist Miloš Urbásek and the experimental musicians Milan Adamčiak and Róbert Cyprich, which was organised as an unofficial parallel to the world skiing championships in the High Tatras. The leitmotif of the First Snow Festival was the recreation of works of art from the Renaissance to the present day; the main material was snow, which the artists used in various ways, interpreting works that seem to have no apparent or direct link to snow or skiing, but which usefully indicate the degree of international contact between artists at this time. Urbásek, for example, painted a series of snowmen in a Homage to Niki de Saint Phalle, while Róbert Cyprich's Cross-Country Homage to Walter de Maria comprised two parallel ski tracks in the snow for fifty kilometres. Milan Adamčiak paid homage to Otto Piene of the Zero Group with a work comprising a burning circle in the snow. Other artists referenced included figures from US Pop (Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, Oldenburg, Segal), European contemporaries (Arman, Christo, Kounellis, Miralda, Uecker) and historical figures such as Brueghel, da Vinci, Malevich and Magritte. The emphasis was on transient material, and playful reappropriation of works of art, amounting to a temporary improvised biennial in the snow.[6]

Other works[edit]

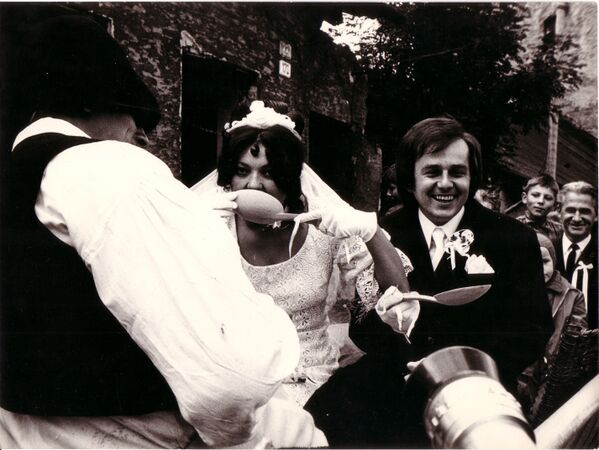

Other works by Mlynárčik took the form of festivals restaging historic works of art, such as Renoir (Moulin de la Galette [Juniones], Piešťany, 1970) and an equestrian painting by Degas (Edgar Degas’ Memorial, Bratislava, 1971), restaged in the form of a horse race, complete with competitions and prizes. Eva's Wedding (Žilina, 1972) was also based on a work of art: the painting Dedinská svatba [Village Wedding] (1946) by the Slovak artist Ľudovít Fulla, whose seventieth anniversary was being celebrated that year.[7]

Ville dei Mysteri [Vila mystérií], 1966-1967. [1]

with Miloš Urbásek, La tentation [Pokušenie], 1967.

Eva's Wedding, 1972. Photograph, 18 x 24 cm. Source.

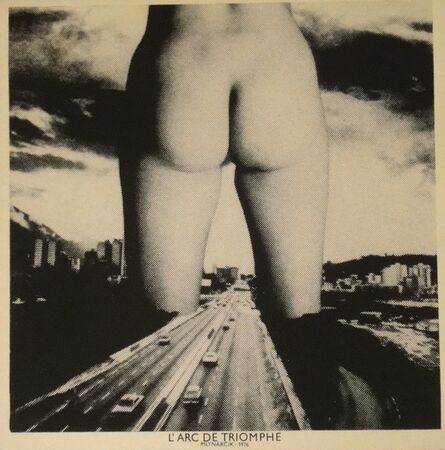

L'Arc de triomphe, 1976. Serigraph, 50 x 50 cm. Source.

Notes[edit]

Writings[edit]

- with Stano Filko and Zita Kostrová, "Čo je HAPPSOC? - skutočnosť (manifest). Teória anonymity", 1 May 1965; repr. in Stano Filko: II., 1965-69. Tvorba. Works-Creations. Werk-Schaffung. Ouvrages, Bratislava: A-Press, 1970; repr. in Pierre Restany, Inde. Alex Mlynárčik, Bratislava: SNG, and Paris: Lara Vincy Gallery, 1995, p 27; repr. in Slovenské výtvarné umenie 1949-1989 z pohľadu dobovej literatúry, ed. Jana Geržová, Bratislava: VŠVU, 2006. (Slovak)

- "Was Ist Happsoc? - Realität (Manifest). Die Theorie der Anonymität", in Stano Filko: II., 1965-69. Tvorba. Works-Creations. Werk-Schaffung. Ouvrages, Bratislava: A-Press, 1970; repr. in Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa, ed. Klaus Groh, Cologne: Dumont, 1972. (German)

- "Quest-ce que nous appelons HAPPSOC? - La réalité (Manifeste)", in Stano Filko: II., 1965-69. Tvorba. Works-Creations. Werk-Schaffung. Ouvrages, Bratislava: A-Press, 1970. (French)

- "What Does HAPPSOC Mean? - Reality (Manifesto). Theory of Anonymity", in Stano Filko: II., 1965-69. Tvorba. Works-Creations. Werk-Schaffung. Ouvrages, Bratislava: A-Press, 1970. (English)

- with Erik Dietmann, "Účastníkom medzinárodného bienále mladých Danuvius 68", 22 Aug 1968; repr. in Pierre Restany, Inde. Alex Mlynárčik, Bratislava: SNG, and Paris: Lara Vincy Gallery, 1995, p 67; repr. in Slovenské výtvarné umenie 1949-1989 z pohľadu dobovej literatúry, ed. Jana Geržová, Bratislava: VŠVU, 2006. (Slovak)

- with Miloš Urbásek, "Manifest o „interpretácii" vo výtvarnom umení", Jun 1969; repr. in Slovenské výtvarné umenie 1949-1989 z pohľadu dobovej literatúry, ed. Jana Geržová, Bratislava: VŠVU, 2006, pp 231-232. (Slovak)

- "Manifesto Concerning 'Interpretation' in Fine Art", trans. Zuzana Flaskova, ed. Sven Spieker, post, New York: MoMA, 2018. [2] (English)

Catalogues[edit]

- Pierre Restany, Inde. Alex Mlynárčik, Bratislava: SNG, and Paris: Lara Vincy Gallery, 1995.

Literature[edit]

- Jindřich Chalupecký, "Příběh Alexe Mlynárčika", in Chalupecký, Na hranicích umění. Několik příběhů, Munich: Arkýř, 1987; Prague: Prostor, 1990, pp 106-122. (Czech)

- Zora Rusinová, "Alex Mlynárčik", in Umenie akcie 1965-1989, ed. Zora Rusinová, Bratislava: Slovenská národná galéria, 2001, pp 21-40. (Slovak)

- Andrea Bátorová, Aktionskunst in der Slowakei in den 1960er Jahren. Aktionen von Alex Mlynárčik, Lit Verlag, 2009, 408 pp. TOC. Based on author's 2007 dissertation. (German)

- Andrea Euringer-Bátorová, Akčné umenie na Slovensku v 60. rokoch 20. storočia. Akcie Alexa Mlynárčika, Bratislava: Slovart, and Bratislava: Vysoká škola výtvarných umení, 2012, 326 pp. Publisher. (Slovak)

- The Art of Contestation: Performative Practices in the 1960s and 1970s in Slovakia, Bratislava: Comenius University, 2019, 216 pp. Review: Bryzgel (ArtMargins). (English)

- Claire Bishop, "Slovakia: Permanent Manifestations", in Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Verso Books, 2012, pp 140-147. (English)

- Boris Kršňák, et al., Ume? Nie! Príbeh zbierky Artandconcept, Bratislava: Petrus, 2020. (Slovak)

Interviews[edit]

- Ján Budaj, "Rozhovor po roku. Rozhovor vo štvorke", in Ján Budaj, 3SD [1981], 2nd ed., samizdat, 1988; repr. in "Samizdatové programové, teoretické a historické texty (výber)", ed. Radislav Matuštík, in Umenie akcie 1965-1989, ed. Zora Rusinová, Bratislava: Slovenská národná galéria, 2001, pp 276-277. Conducted 6 June 1981. (Slovak)

- "Conversation in an unrated pub", trans. Jana Krajnakova, in 1968-1989: Political Upheaval and Artistic Change, eds. Claire Bishop and Marta Dziewańska, Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2009, pp 223-225. Translated from the second edition of Budaj's samizdat publication 3SD (1988). (English)

Documentary film[edit]

See also[edit]

- Deň radosti (A Day of Joy), documentary film by Dušan Hanák about Mlynárčik's If All Trains of the World performance (1971)

- VAL

- Sound art in Slovakia (1960s-2000s)

Links[edit]

- Biography and works in CEAD

- Biography and selected works on artandconcept.eu

- Alex Mlynárčik: Závery 89. zjazdu už nesplníme, public art installation, Stanica, Žilina, 2009.