Hugo Ball

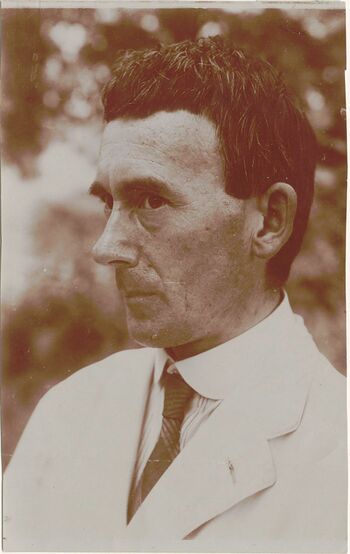

Hugo Ball, Zürich, c.1921. Photo: Hans Holdt. [9] | |

| Born |

February 22, 1886 Pirmasens, German Empire |

|---|---|

| Died |

September 14, 1927 (aged 41) Sant'Abbondio, Switzerland |

| Web | UbuWeb Sound, Dada Companion, Wikipedia |

Hugo Ball (1886–1927) was a German author, poet and one of the leading Dada protagonists.

Contents

Life and work[edit]

Born into a strict and highly devout Catholic family, Hugo Rudolf Ball was a sensitive child, who grew up fearing the severity of his mother's faith. As a young man, he was apprenticed to a leather factory, but after suffering a nervous breakdown, he was allowed by his family to attend university in Munich and Heidelberg, where he studied German literature, philosophy, and history, and began a dissertation on Friedrich Nietzsche. Describing his search for philosophical meaning as "my problem, my life, my suffering," Ball devoted himself to intense study, reading widely across various systems of thought, including German moral philosophy, Russian anarchism, modern psychoanalysis, and Indian and early Christian mysticism. It was Ball who provided the Dada movement in Zurich with the philosophical roots of its revolt.

From 1910 to 1913 Ball embarked on a career in the theater, first studying acting with Max Reinhardt and then working as a director and stage manager for various theater companies in Berlin, Plauen, and Munich. His ambition was to develop a theater modeled on the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk—a synthesis of all the arts—that could motivate social transformation and rejuvenation. He also began writing, contributing critical reviews, plays, poems, and articles to the expressionist journals Die Neue Kunst [The New Art] and Die Aktion, both of which, in style and in content, anticipated the format of later Dada journals. In Die Aktion, poems written jointly by Ball and Hans Leybold appeared under the pseudonym Ha Hu Baley. Leybold, a young and rebellious expressionist writer, was one of Ball's best friends and an active influence on his intellectual development. Also important to the formation of Ball's ideas, especially during the Dada period, were Vasily Kandinsky, the abstract painter and leader of the expressionist Blaue Reiter group, and Richard Huelsenbeck, a young doctor and student who would later become central to Dada in Zurich and Berlin, both of whom he met for the first time in Munich in 1912–1913.

In 1914 Ball applied for military service three times and was rejected on each occasion for medical reasons. The trauma he experienced when he took a private trip to the front in Belgium prompted him to abandon the theater and move to Berlin, where he began to delve into political philosophy, especially the anarchist writings of Peter Kropotkin and Mikhail Bakunin. He began writing a book on Bakunin that would continue to occupy him for the rest of his life. With Huelsenbeck, Ball staged several antiwar protests in Berlin, the first of which took place in February 1915 and was a memorial to fallen poets, including Hans Leybold, who had been mortally wounded at the front. Other expressionist evenings hosted by Ball and Huelsenbeck included the kind of aggressive and theatrical readings that would characterize Dada performances.

In mid-1915 Ball and Emmy Hennings, a cabaret singer whom he had met in Munich and whom he would marry in 1920, left Berlin for neutral Zurich. There, in February 1916, after stints with theatrical companies and vaudeville troupes, they opened the Cabaret Voltaire. At the Cabaret, Ball was organizer, promoter, performer, and the primary architect of Dada's philosophical activism. He advocated the intentional destruction and clearing away of the rationalized language of modernity that for him represented all that had led to the "agony and death throes of this age." His poetry was an attempt to "return to the innermost alchemy of the word" in order to discover, or to found, a new language untainted by convention. One of Ball's most innovative poetic forms was the sound poem, a string of noises which, when premiered at the Cabaret in June 1916, he performed with a mesmerizing, almost liturgical intensity. In his diary account of the reading, Ball recorded how his chanting had transported him back into his childhood experience of Mass, leaving him physically and emotionally exhausted.

In July 1916 Ball left the Dada circle in Zurich in order to recuperate in the small village of Vira-Magadino in the Swiss countryside. When he returned in January 1917, it was at the request of Huelsenbeck and Tristan Tzara, who wanted him to help organize Galerie Dada, an exhibition space that opened in March 1917. Events at the Galerie included lectures, performances, dances, weekend soirées, and tours of the exhibitions. Although Ball supported the educative goals of the Galerie, he was at odds with Tzara over Tzara's ambition to make Dada into an international movement with a systematic doctrine. He left Zurich in May 1917 and did not again actively participate in Dada activities.

By the end of 1917 Ball was living in Bern, writing for the radical Die Freie Zeitung [The Free Newspaper], an independent paper for democratic politics. Ball contributed articles on German and Soviet politics, propaganda, and morality. He also returned to his study of Bakunin and prepared a manuscript of his 1915 Zur Kritik der deutschen Intelligenz [Critique of the German Intelligentsia] for publication. The Critique was a virulent attack on Prussian militarism and its effect on German culture that Ball had written partly in response to the nationalistic fervor that gripped Germany during World War I.

After 1920, when he and Hennings moved to the small Swiss village of Agnuzzo, Ball became increasingly mystical and removed from political and social life, returning to a devout Catholicism and plunging into an ambitious study of fifth- and sixth-century Christian saints. He began revising his personal diaries for the years 1910–1921, and in 1927 these writings were published as Die Flucht aus der Zeit (Flight Out of Time). Containing philosophical writings and acute observations of Dada performances and personalities, it remains one of the seminal documents of the Dada movement in Zurich. (Source)

Portraits[edit]

Hugo Ball, 1916. [1]

Hugo Ball, c.1921. [2]

Emmy Hennings and Hugo Ball, Agnuzzo, 1921. [3]

Annemie Schütt-Hennings, Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, Albori, 1925. [4]

Annemie Schütt-Hennings, Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, Salerno, 1926. [5]

Works[edit]

Recordings[edit]

Publications[edit]

- Die Nase des Michelangelo. Tragikomödie in vier Auftritten, Leipzig: Ernst Rowohlt, 1911, 71 pp. (German)

- Der Henker von Brescia: drei Akte der Not und Ekstase [1914], ed. Franz L. Pelgen, afterw. Hansjörg Viesel, Leipzig: Faber & Faber, 1995, 80 pp. (German)

- editor, Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich: Meierei, 1916, 31 pp, KHZ, UbuWeb, IDL. Single-issue magazine. (German),(French)

- Flametti, oder, Vom Dandysmus der Armen. Roman, Berlin: Erich Reiss, 1918, 224 pp, KHZ, IDA, IDA. Novel. (German)

- Flametti, eller, De fattigas dandyism: roman, trans. Dagmar Bergh-Palmros, Helsingfors: Schildt, 1920, 227 pp. (Swedish)

- Flametti, avagy, a szegények dandyzmusa, trans. Péter Nemes, Budapest: József Attila Kör, and Pécs: Jelenkor, 1998, 194 pp. (Hungarian)

- Flametti, o, Del dandismo dei poveri, trans. Piergiulio Taino, Pasian di Prato: Campanotto, 2006, 270 pp. (Italian)

- Flametti, ou, Du dandysme des pauvres, trans. Pierre Gallissaires, Senouillac: Vagabonde, 2013, 248 pp. (French)

- Flametti, o, El dandismo de los pobres: una novela sobre la prehistoria del dadaísmo, trans. & notes Fernando González Viñas, Córdoba: Berenice, 2013, 261 pp. (Spanish)

- Flametti or the Dandyism of the Poor, trans. Catherine Schelbert, intro. Marc Dachy, Cambridge, MA: Wakefield Press, 2014, 169 pp. (English)

- Flametti, aneb, O dandysmu chudých, trans. Věra Koubová, Prague: Rubato, 2016, 229 pp. (Czech)

- Zur Kritik der deutschen Intelligenz, Bern: Der Freie Verlag, 1919, 327 pp, KHZ, DTA, IDA, IDA; new ed., rev., as Die Folgen der Reformation, Munich: Duncker & Humblot, 1924. (German)

- Crítica de la inteligencia alemana, trans. J.M. Pomares, intro. Hermann Hesse and G.H. Kaltenbrunner, Barcelona: Edhasa, 1971, 326 pp. (Spanish)

- Critique of the German Intelligentsia, trans. Brian L. Harris, intro. Anson Rabinbach, Columbia University Press, 1993, xlii+273 pp. (English)

- Critica dell'intellettuale tedesco, trans. Piergiulio Taino, Udine: Campanotto, 2007, 191 pp. (Italian)

- Crítica de la inteligencia alemana, intro. Germán Cano, Palencia: Capitán Swing Libros, 2011, 302 pp. (Spanish)

- Tenderenda der Phantast. Roman [1914-1920], Zürich: Arche, 1967, 135 pp; repr., eds. Raimund Meyer and Julian Schütt, Innsbruck: Haymon, 1999; new ed., ed. & afterw. Klaus Detjen, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2015. Novel. [10] (German)

- Tenderenda roman, trans. & intro. Cecilia Hansson, Lund: Coyote, 1994, 77 pp. (Swedish)

- "Tenderenda the Fantast", trans. Malcolm Green, in Hugo Ball, Richard Huelsenbeck, Walter Serner, Blago Bung, Blago Bung, Bosso Fatakal: First Texts of German Dada, ed. Malcolm Green, London: Atlas Press, 1995. (English)

- Tenderenda de fantast, trans. Jan H. Mysjkin, Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2000, 93 pp. (Dutch)

- Ball and Hammer: Hugo Ball's Tenderenda the Fantast, intro., ed. & notes Jeffrey T. Schnapp, trans. Jonathan Hammer, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, x+134 pp. (English)

- Tenderenda el fantástico, trans. Jorge Segovia and Violetta Beck, Vigo: Maldoror, 2005, 116 pp. (Spanish)

- Tenderenda le fantasque, trans. Pierre Galissaires, Paris: Vagabonde, 2005, 139 pp. (French)

- Fantasten tenderenda, trans. Peter Laugesen, Copenhagen: Bebop, 2009, 101 pp. (Danish)

- Tenderenda fantasta, trans. Věra Koubová, Prague: Rubato, 2016, 113 pp. (Czech)

- Byzantinisches Christentum. Drei Heiligenleben (zu Joannes Klimax, Dionysius Areopagita und Symeon dem Styliten), Munich: Duncker & Humblot, 1923; new ed., ed. & comm. Bernd Wacker, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2011. (German)

- Dionysios Areopagita, intro. Robert Braun, afterw. Daniel Andreae, trans. Alf Ahlberg, Stockholm: Natur och kultur, 1958, 191 pp. (Swedish)

- Vizantijskoe christianstvo, trans. A.P. Shurbelyev, St. Petersburg: Vladimir Dalʹ, 2008, 379 pp. (Russian)

- Cristianesimo bizantino: vite di tre santi, trans. Piergiulio Taino, Milan: Adelphi, 2015, 316 pp, EPUB. (Italian)

- Cristianismo bizantino: tres vidas de santos, trans. Fernando González Viñas, afterw. Bernd Wacker, Córdoba: Berenice, 2016, 467 pp. (Spanish)

- Bizantinsko krščanstvo: življenje treh svetnikov, trans. Alfred Leskovec, afterw. Tadej Rifel, Ljubljana: KUD Logos, 2016, 288 pp. (Slovenian)

- Hermann Hesse. Sein Leben und sein Werk, Berlin: S. Fischer, 1927, 242 pp, PDF, PDF. (German)

- Hermann Hesse: la vita e le opere, intro. & trans. Stefano Masi, Padova: Liviana, 1993, xv+173 pp. (Italian)

- Hermann Hesse: sa vie et son oeuvre, trans. Sabine Wolf, Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2000, 188 pp. (French)

- Hermann Hesse: su vida y su obra, trans. Carlos Fortea Gil, Barcelona: Acantilado, 2008, 219 pp. (Spanish)

- Die Flucht aus der Zeit, Munich: Duncker & Humblot, 1927, 330 pp, KHZ; new ed., forew. Herman Hesse, Munich: Kösel & F. Pustet, 1931, 330 pp; new ed., forew. Emmy Ball-Hennings, Luzern: J. Stocker, 1946, xxix+311 pp; new ed., ed., notes & afterw. Bernhard Echte, Zürich: Limmat, 1992, 365 pp. Diary. (German)

- Flight Out of Time: A Dada Diary, ed. & intro. John Elderfield, trans. Ann Raimes, New York: Viking Press, 1974, lxiv+254 pp; new ed., University of California Press, lxiv+274 pp. (English)

- Jidai kara no tōsō: dada sōritsusha no nikki [時代からの逃走: ダダ創立者の日記], trans. Yoshio Dohi and Kōichi Kondō, Tokyo: Misuzushobō, 1975. (Japanese)

- La fuite hors du temps: journal 1913-1921, trans. Sabine Wolf, Monaco: Rocher, 1993, 386 pp. (French)

- Flykten ur tiden, trans., comm. & afterw. Cecelia Hannson, Lund: Ellerstroms, 2000, 254 pp. (Swedish)

- La huida del tiempo: un diario, con el primer manifiesto dadaísta, forew. Paul Auster, trans. Roberto Bravo de la Varga, Barcelona: Acantilado, 2005, 373 pp. (Spanish)

- La fuga dal tempo: fuga saeculi, trans. Pier Giulio Taino, Pasian di Prato: Campanotto, 2006, 191 pp. (Italian)

- De vlucht uit de tijd, trans. Hans Driessen, Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2016, 351 pp. (Dutch)

- Útěk z doby, trans. Nikola Mizerová and Pavel Novotný, Prague: Rubato, 2016, 390 pp. (Czech)

- Collected works

- Gesammelte Gedichte mit Photos und Faksimiles, ed. Annemarie Schütt-Hennings, Zürich: Arche, 1963. (German)

- Sämtliche Werke und Briefe, 10 vols., Göttingen: Wallstein, 2003-2011. Incl. correspondence (1904-1927): ARG, v.10/1, ARG, v.10/2, ARG, v.10/3. (German)

- Selected works

- Litania till den helige Hugo: texter om och av Hugo Ball, trans., intro. & comm. Cecilia Hansson, Lund: Coyote, 1997, 78 pp. (Swedish)

- Ausgewaehlte Gedichte, 2010. (German)

- Bagatelle, ed. Elena Moreno Sobrino, ills. Louis Houtin, Saarbrücken: Calambac, 2014. (German)

- Die Katze, ed. Elena Moreno Sobrino, ills. Nele Aron, Saarbrücken: Calambac, 2014. (German)

- O, Großpapa, o Graspopo, ed. Elena Moreno Sobrino, ills. Ando Ueno, Saarbrücken: Calambac, 2014. (German)

- Correspondence

- Briefe 1911-1927, Benziger, 1957. (German)

- More

Literature[edit]

- Emmy Ball-Hennings (ed.), Hugo Ball. Sein Leben in Briefen und Gedichten, forew. Hermann Hesse, Berlin: Fischer, 1929, 312 pp. (German)

- Emmy Ball-Hennings, Hugo Balls Weg zu Gott: ein Buch der Erinnerung, Munich: Josef Kösel, 1931, 189 pp. (German)

- Emmy Ball-Hennings, Ruf und Echo: mein Leben mit Hugo Ball, Einsiedeln: Benziger, 1953, 291 pp; repr., afterw. Christian Döring, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1990, 313 pp. (German)

- Hugo Ball Almanach, 30 vols., ed. Stadt Pirmasens, Pirmasens, 1977-2006. Published annually. (German)

- Philip Mann, Hugo Ball: An Intellectual Biography, London: University of London, Institute of Germanic Studies, 1987. (English)

- Sabine Werner-Birkenbach, Hugo Ball und Hermann Hesse – eine Freundschaft, die zu Literatur wird. Kommentare und Analysen zum Briefwechsel, zu autobiographischen Schriften und zu Balls Hesse-Biographie, Stuttgart: Akademischer Verlag, 1995. (German)

- Bernd Wacker, Dionysios DADA Areopagita. Hugo Ball und die Kritik der Moderne, Paderborn: Schöningh, 1996. (German)

- Renée Riese Hubert, "Zurich Dada and Its Artist Couples", in Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, ed. Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, MIT Press, 1998, pp 516-545. (English)

- Tom Sandqvist, Kärlek och dada: Hugo Ball och Emmy Hennings, Stockholm: Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposion, 1998, 367 pp. (Swedish)

- Erika Süllwold, Das gezeichnete und ausgezeichnete Subjekt. Kritik der Moderne bei Emmy Hennings und Hugo Ball, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 1999, 325 pp. (German)

- Cornelius Zehetner, Hugo Ball. Portrait einer Philosophie, Vienna: Turia & Kant, 2000. (German)

- Hal Foster, "Dada Mime", October 105: "Dada", Summer 2003, pp 166-176. (English)

- Christoph Schmidt, Die Apokalypse des Subjekts. Ästhetische Subjektivität und politische Theologie bei Hugo Ball, Bielefeld: Aisthesis, 2003. (German)

- Eva Zimmermann, Bernhard Echte, Regina Bucher (eds.), Hugo Ball. Dichter, Denker, Dadaist, Wädenswil: Nimbus, 2007. (German)

- Hugo Ball Almanach. Neue Folge, eds. Stadt Pirmasens and Hugo-Ball-Gesellschaft, Munich: text+kritik, 2010ff. Published annually. (German)

- Michael Braun, Hugo Ball. Der magische Bischof der Avantgarde, Heidelberg: Das Wunderhorn, 2011. (German)

- Wiebke-Marie Stock, Denkumsturz. Hugo Ball. Eine intellektuelle Biographie, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2012. (German)

- Bärbel Reetz, Das Paradies war für uns. Emmy Ball-Hennings und Hugo Ball, Berlin: Insel, 2015, 477 pp. (German)

- Alfred Sobel, „Gute Ehen werden in der Hölle geschlossen“. Das wilde Leben des Künstlerpaares Hugo Ball und Emmy Hennings zwischen Dadaismus und Glaube, Kißlegg: Fe-Medienverlag, 2015. (German)

- Emily Hage, "A 'Living Magazine': Hugo Ball's Cabaret Voltaire", The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory 91:4, 2016, 395-441.

- Eveline Hasler, Und werde immer Ihr Freund sein. Hermann Hesse, Emmy Hennings und Hugo Ball, Nagel & Kimche, 2017. (German)