MAVO

MAVO was formed in July 1923 through the union of two new forces in Japanese Western-style art (yoga): the artist Tomoyoshi Murayama, self-proclaimed interpreter of European modernism, and the already established Japanese Futurist art movement. Nearly all the artists involved in Mavo had previously participated in the Miraiha Bijutsu Kyokai (Futurist Art Association). In addition to Murayama, Mavo's initial membership included four former Futurists: Masamu Yanase, Kamenosuke Ogata, Shuzo Oura, and Shinro Kadowaki. There were a number of different explanations of Mavo's naming, all of which differed on key points but generally served the important purpose of giving the group an enigmatic and stylish aura.

After its founding, Mavo quickly expanded to include Osamu Shibuya, Shuichiro Kinoshita, Iwane Sumiya, Tatsuo Okada, Michinao Takamizawa, Kimimaro Yabashi, Tatsuo Toda, Masao Kato, and Kyojiro Hagiwara, among others. Until the group's dissolution at the end of 1925, Mavo artists engaged in diverse artistic activities including the publication of a magazine, art criticism, book illustration, poster design, dance and theatrical performances, and architectural projects. (Source)

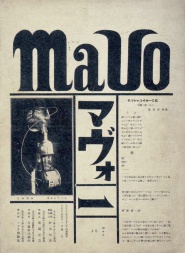

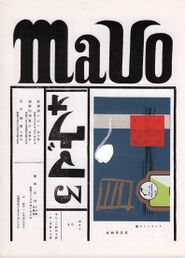

Magazine

MAVO magazine was edited by Tatsuo Okada and Tomoyoshi Murayama and appeared in 7 issues between July 1924 and August 1925. By the third issue, the magazine was thick with advertisements and the usage of actual newspaper as its pages [1].

The contents were thematically diverse and included essays on art (which often touched on sociocultural issues), poetry, and short theatrical texts. Throughout the pages were original linocuts and photographic reproductions of assemblage, painting, and graphic works. Oftentimes, these photographs were incorporated into new collages in the magazine itself. A Mavo trademark was the group's recycling of materials and elements from other projects in a continuous effort to refer back to their own artistic production. [2]

- Reprint

- Nihon Kindai Bungakkan, Tokyo, 1991.

Publications

(in Japanese)

- "Mavo Manifesto", in the pamphlet for the first Mavo exhibition at Denpōin Temple in Asakusa, 1923; repr. in Nihon no Dada 1920-1970, ed. Yoshio Shirakawa, Tokyo: Hakuba Shobō and Kazenobara, 1988, pp 35-36.

- Tomoyoshi Murayama, Ichimei ishikiteki kōsei shugi e no dōtei [現在の藝術と未來の藝術 一名、意識的構成主義への道程], 1924.

- Artists' books

- Hagiwara Kyōjirō, Shikei senkoku [Death Sentence], Tokyo: Chōryūsha, 1925, 161+6 pp. Illustrated by Mavo. Anthology of visual poetry. [3]

- Ernst Toller, Tsubame no sho [The Swallow Book], trans. Tomoyoshi Murayama, Tokyo: Chōryūsha, 1925, 106 pp. Illustrated by Tatsuo Okada. [4]

- Hideo Saito, Aozameta douteikyo [The Pale-Faced Virgin's Mad Thoughts], Tokyo: Chōryūsha, 1926, 120 pp. Illustrated by Tatsuo Okada. Anthology of visual poetry. [5] [6]

Literature

- Gennifer Weisenfeld, "Mavo's Conscious Constructivism: Art, Individualism, and Daily Life in Interwar Japan", Art Journal 55:3 (Autumn 1996), pp 64-73.

- William Gardner, "詩と新メディア : 萩原恭次郎の「広告塔!」を中心にした一九二〇年代のアヴァンギャルド論考" [Poetry and New Media: An Essay on the 1920's Avant-garde, Forcusing on Hagiwara Kyojiro's "Advertising Tower !"], Comparative Literature and Culture 16 (1999). (in Japanese)

- Gennifer Weisenfeld, Mavo: Japanese Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1905-1931, University of California Press, 2002, 368 pp.

See also

Links

- http://www.japandesign.ne.jp/HTM/REPORT/art_review/25/index4.html

- http://hiroyasu-tangerine.blogspot.com/2010/11/mavo.html

- http://comic-mavo.com/index.php?id=59

- http://mavo.takekuma.jp/manga/memo/aboutmavo.html

- http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/MAVO

| Avant-garde and modernist magazines | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Poesia (1905-09, 1920), Der Sturm (1910-32), Blast (1914-15), The Egoist (1914-19), The Little Review (1914-29), 291 (1915-16), MA (1916-25), De Stijl (1917-20, 1921-32), Dada (1917-21), Noi (1917-25), 391 (1917-24), Zenit (1921-26), Broom (1921-24), Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet (1922), Die Form (1922, 1925-35), Contimporanul (1922-32), Secession (1922-24), Klaxon (1922-23), Merz (1923-32), LEF (1923-25), G (1923-26), Irradiador (1923), Sovremennaya architektura (1926-30), Novyi LEF (1927-29), ReD (1927-31), Close Up (1927-33), transition (1927-38). | ||

| Full list | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Entretiens politiques et littéraires (1890-93), Moderní revue (1894-1925), Volné směry (1897-1948), Mir iskusstva (1898-1904), Vesy (1904-09), Poesia (1905-09, 1920), Zolotoe runo (1906-10), The Mask (1908-29), Apollon (1909-17), Ukraïnska khata (1909-14), Der Sturm (1910-32), Thalia (1910-13), Rhythm (1911-13), Trudy i dni (1912), Simbolul (1912), The Glebe (1913-14), Ocharovannyi strannik (1913-16), Revolution (1913), Blast (1914-15), The Little Review (1914-29), Futuristy (1914), Zeit-Echo (1914-17), The Egoist (1914-19), L'Élan (1915-16), 291 (1915-16), Orpheu (1915), La Balza futurista (1915), MA (1916-25), SIC (1916-19), flamman (1916-21), The Blindman (1917), Nord-Sud (1917-18), De Stijl (1917-20, 1921-32), Dada (1917-21), Klingen (1917-20, 1942), Noi (1917-25), 391 (1917-24), Modernisme et compréhension (1917), Anarkhiia (1917-18), Iskusstvo kommuny (1918-19), Formiści (1919-21), S4N (1919-25), La Cité (1919-35), Aujourd'hui (1919), Exlex (1919-20), L'Esprit nouveau (1920-25), Orfeus (1920-21), Action (1920-22), Proverbe (1920-22), Ça ira (1920-23), Zenit (1921-26), Kinofon (1921-22), Het Overzicht (1921-25), Jednodńuwka futurystuw (1921), Nowa sztuka (1921-22), Broom (1921-24), Život (1921-48), Creación (1921-24), Jar-Ptitza (1921-26), New York Dada (1921), Aventure (1921-22), Spolokhi (1921-23), Gargoyle (1921-22), Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet (1922), Kino-fot (1922-23), Le Coeur à barbe (1922), Die Form (1922, 1925-35), 7 Arts (1922-28), Manomètre (1922-28), Ultra (1922), Út (1922-25), Dada-Jok (1922), Dada Tank (1922), Dada Jazz (1922), Mécano (1922-23), Contimporanul (1922-32), Zwrotnica (1922-23, 1926-27), Secession (1922-24), Stavba (1922-38), Gostinitsa dlya puteshestvuyuschih v prekrasnom (1922-24), Putevi (1922-24), Klaxon (1922-23), Akasztott Ember (1922-23), MSS (1922-23), Perevoz Dada (1922-49), Egység (1922-24), L'Architecture vivante (1923-33), Merz (1923-32), LEF (1923-25), G (1923-26), The Next Call (1923-26), Russkoye iskusstvo (1923), Disk (1923-25), Irradiador (1923), Surréalisme (1924), Almanach Nowej Sztuki (1924-25), La Révolution surréaliste (1924-29), Blok (1924-26), Pásmo (1924-26), DAV (1924-37), Bulletin de l'Effort moderne (1924-27), ABC (1924-28), CAP (1924-28), Athena (1924-25), Punct (1924-25), 75HP (1924), Le Tour de Babel (1925), Periszkop (1925-26), Integral (1925-28), Praesens (1926, 1930), Sovremennaya architektura (1926-30), bauhaus (1926-31), Das neue Frankfurt (1926-31), L'Art cinématographique (1926-31), Dokumentum (1926-27), Kritisk Revy (1926-28), Novyi LEF (1927-29), i 10 (1927-29), Nova generatsiia (1927-30), ReD (1927-31), Dźwignia (1927-28), Tank (1927-28), Close Up (1927-33), Horizont (1927-32), transition (1927-38), Discontinuité (1928), Munka (1928-39), Quosego (1928-29), Urmuz (1928), Unu (1928-32), Revista de Antropofagia (1928-29), 50 u Evropi (1928-29), Documents (1929-30), L'Art Contemporain - Sztuka Współczesna (1929-30), Adam (1929-40), Art concret (1930), Zvěrokruh (1930), Alge (1930-31), Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution (1930-33), Levá fronta (1930-33), Kvart (1930-37, 1945-49), Nová Bratislava (1931-32), Linja (1931-33), Spektrum (1931-33), Nadrealizam danas i ovde (1931-32), Ulise (1932-33), Die neue Stadt (1932-33), Mouvement (1933), PLAN (1933-36), Karavan (1934-35), Ekran (1934), Axis (1935-37), Acéphale (1936-39), Telehor (1936), aka (1937-38), Plastique (1937-39), Plus (1938-39), Les Réverbères (1938-39). | ||