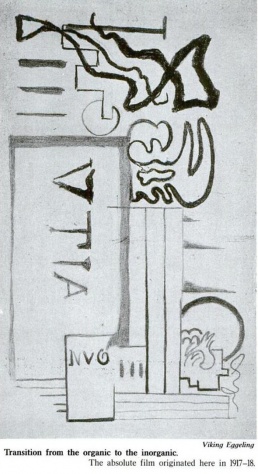

Viking Eggeling

Viking Eggeling, c1925. From El Lissitzky & Hans Arp, Die Kunstismen/Les Ismes De L’Art/The Isms of Art: 1914-1924, 1925. | |

| Born |

October 21, 1880 Lund, Sweden |

|---|---|

| Died |

May 19, 1925 (aged 44) Berlin, Germany |

Viking Eggeling was an avant-garde artist and filmmaker connected to Dada, Constructivism and Abstract art and was one of the pioneers in absolute film and visual music. His 1924 film Symphonie diagonale [Diagonal Symphony] is one of the seminal abstract films in the history of experimental cinema.

Life and work

Family

Helmut Viking Fredrik Eggeling grew up in Lund, Sweden, as the youngest child in a large family of Fredrik Eggeling (1822-1895) and his second wife, Elisabeth Lundborg (1839-1889). He had eleven siblings, the oldest born in 1852. His father immigrated to Sweden from Nieder-Sachsen, Germany, around 1850, and opened a music shop [Eggelings musikhandel] in Lund and worked as a music teacher.[1]

Early years

Viking was orphaned in 1895 and two years later in May he moved to Germany, where he began commercial training at Flensburg. He shortly worked as a bookkeeper at a watch-factory at Le Locle in Switzerland (c1900), then moved to Milan (c1901-1907), where he was taking night classes at the Brera Academy and took up studying art history, determined to become an artist. In 1903 he married Nora Sidney Marie (Noné) Fiernkranz from Vienna. In 1907 he worked as a drawing-master at the Lyceum Alpinum at Zuoz in Switzerland, briefly visiting Berlin in 1910. Over the whole decade he had supported himself with work as a bookkeeper.[2]

Paris, Zürich and Dada (c1911-19)

From c1911 to c1915 he lived in Paris, probably after separating from his wife. There he was acquainted with Amedeo Modigliani, Jean Arp, Othon Friesz, Moise Kisling. Modigliani painted his portrait in 1916. At this point his art was influenced by Cubism, but soon grew more abstract. He never dated and only rarely signed his works.[3]

In the years c1915-1917 he lived first at Ascona and later other places in Switzerland, with his wife Marion, née Klein. During this time, he started working on his 'universal language', a theory of harmony for painting which was to open up a way for meaningful communication between viewer and artist.[4]

During one of his stays at the Mount Verita Lebensreform colony at Anconà, Italy, Eggeling met the author Yvan Goll, one of the principle advocates of film as art amongst German literary circles. In 1920, Goll published the article entitled Das Kinodram where he states emphatically that “the basis of all future art is the cinema.” During 1918 Goll helped Eggeling with first preliminary works for the latter’s abstract film (probably Horizontal-Vertikal-Messe) cutting geometrical forms and mounting them onto the celluloid support. According to Claire Goll, the two also discussed the foundations of abstract film which Goll still called Kinomalerei [cinema-painting].[5]

In c1918 Viking and Marion settled down in Zürich. There he re-connected with Jean Arp and took part in several Dada activities, befriending Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Sophie Taeuber, and the other dadaists connected to the Cabaret Voltaire. In March 1919 he also joined the group Das neue Leben [New Life], started the year before in in Basel by Arp, Fritz Baumann, Augusto Giacometti, Janco, Taeuber, and Otto Morach, among others. The group supported an educational approach to modern art, coupled with socialist ideals and Constructivist aesthetics. In its art manifesto, the group declared its ideal of "rebuild[ing] the human community" in preparation for the end of capitalism. In April 1919 Eggeling was co-founder of the similar group Radikale Künstler [Radical Artists], a more political section of Das neue Leben group, that also counted Hans Richter.[6]

Eggeling's major concern during this period was to find a medium for the metaphysical problems which obsessed him, to articulate his forms of "universelle Sprache" [universal language] in order that they should serve as 'communication signs'. He was to give expression to these speculations in many hundreds of studies, until he finally gave shape to his form language in the large scroll drawings, which in their turn were to serve as models (score) for his later film experiments. Eggeling executed these scrolls during his years in Switzerland and showed them to his colleagues Arp, Tzara, Janco, and Richter.[7]

Viking Eggeling, 1919. Drawing by Marcel Janco.

Collaboration with Richter (1919-21)

In 1918 Eggeling had through Tristan Tzara been introduced to Hans Richter. When the Dada group began to break up in the summer of 1919, Richter invited Eggeling to come with him to Germany and stay at his parents' estate in Klein-Kölzig, 150km south-east of Berlin.[8] There they would continue to work intimately on form studies and experiments for over two years.

In Germany their first stop was Berlin, where he met with Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch and other artists. Here he also joined the Novembergruppe [November Group], a radical political group that featured many artists connected to Dada, Bauhaus and Constructivism.[9]

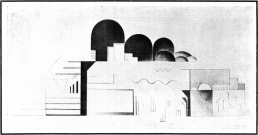

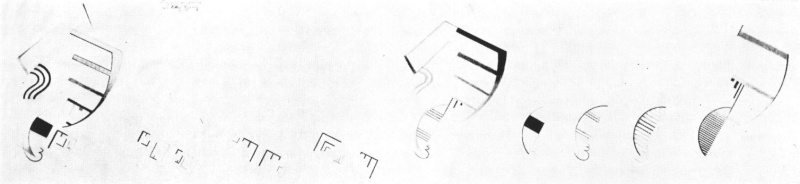

Towards the end of 1919 he moved to Klein-Kölzig to accompany Richter. Eggeling probably separated from his wife in c1920 and stayed on alone with the Richter family.[10] He continued his experiments with "picture rolls". These scrolls were sequences of painted images on long rolls of paper that investigate the transformation of geometrical forms and could be up to 15 meters in length. As they were to be "read" from left to right, this soon evolved into cinematographic experimentation on film stock.

Neither artist knew any of the technical rudiments of filmmaking. So, in 1920 the pair decided to start a campaign to persuade UFA (Universum-Film A.G.) in Berlin to produce their film. They had the idea of producing, as a part of this campaign, an 8-page pamphlet, Universelle Sprache [Universal Language], which would set out their ideas about a language of elementary pictorial elements, and which they could likewise send out to people of influence (Albert Einstein among others). Their campaign was successful, for UFA provided them with a studio and a technician.[11]

Eggeling's first scroll drawings, Horizontal-Vertikal-Messe I-III [Horizontal-vertical Orchestra], served as a synopsis or score for these initial film experiments, while Richter worked on his Präludium. They contacted Theo van Doesburg, who paid them a visit in Klein-Kölzig, first for three days but remained three weeks, and in May 1921 reported about their film experiments in De Stijl. Articles in other journals followed. In August 1921, Eggeling published his manifesto in the Hungarian journal MA (the same year its extended version appeared in De Stijl under Richter's sole name[12]).[13] A book which has probably had a major influence on Eggeling when he was formulating his theories, is Kandinsky's Über das Geistige in der Kunst.[14]

In the end, however, the UFA technician and the artists did not get along and the resulting collaboration was a disaster. Eggeling’s first UFA animation tests (1920/21) were so unsatisfactory that he would not show them in public.[15]

Following a difference with Richter, Eggeling broke off their collaboration some time towards the end of 1921 and moved to Berlin.[16][17]

In one version of his encounter with Eggeling, Richter said the following (in Richter, "Avant-Garde Film in ", 1949):

"I spent two years, 1916–1918, groping for the principles of what made for rhythm in painting. [...] In 1918, Tristan Tzara brought me together with a Swedish painter from Ascona, who, as he told me, also experimented with similar problems. His name was Viking Eggeling. His drawings stunned me with their extraordinary logic and beauty, a new beauty. He used contrasting elements to dramatize two (or more) complexes of forms and used analogies in these same complexes to relate them again. In varying proportions, number, intensity, position, etc., new contrasts and new analogies were born in perfect order, until there grew a kind of ‘functioning’ between the different form units, which made you feel movement, rhythm, continuity... as clear as in Bach. That’s what I saw immediately!"

Berlin (from 1921) and Symphonie diagonale (1923-25)

In Berlin Eggeling installed himself at Wormserstrasse 6a, near Wittenbergplatz, Charlottenburg, in a primitive studio which was freezingly cold in winter, hot and stuffy in summer. After a brief to his sister in Sweden in the summer of 1922, he bought a film camera and a projector, both of them manually operated. Eggeling constructed an animation table, a simple box covered with a sheet of glass, and made himself a dark room in a space adjoining the studio.[18]

His friends and acquaintances counted Erich Buchholz, Raoul Hausmann, Werner Graeff, Arthur Segal, El Lissitzky, Naum Gabo, Nathan Altmann, Hannah Höch, Zhenia Bogoslavskaya, Henryk Berlewi, Kurt Schwitters and others. In October 1922, Berlin saw the First Russian Art Exhibition, the first complete presentation of the new Soviet abstract art in the West.[19]

Axel Olson, then a young Swedish artist who was staying in Berlin to study under Archipenko, wrote to his parents in November 1922 that Eggeling was working "to evolve a musical-cubistic style of film - completely divorced from the naturalistic style which he considers lunatic and scandalous".[20]

During 1922 and 1923 Eggeling attempted several more animation tests with Horizontal-Vertikal-Messe, but they still seemed inadequate. In the summer of 1923 via Werner Graeff he met Erna Niemeyer, then a Bauhaus student who just finished her second year in Weimar, and who undertook to animate his Symphonie diagonale [Diagonal Symphony] scrolls[21]. At this point, Eggeling abandoned the Horizontal-Vertikal-Messe entirely. For over a year, the two worked on a new film in his studio flat, in appalling poverty. The Ascania-Werke placed some of the necessary apparatus at his disposal, and one of their engineers, who was interested in Eggeling's film experiments, used to help him when some detail in the technical equipment did not function as it should. At the beginning of the experiments the separate elements of the composition were cut out of black sheets of paper, but later tin-foil was used, which proved more suitable. The film was made by the usual technique for animated film, ie. single frame exposures (stop-motion photography).[22]

While working on Symphonie diagonale, inspired by Henri Bergson's L'évolution créatrice of 1907 (particularly its 1912 German edition[23]), Eggeling was evolving a theory based on his film experiments and his studies of form and colour. He called his theory Eidodynamik [visual dynamics], a name thought up for him by his close friend Charlotte Wolff[24]. Little is known about it, but the fundamental principle was the projection of coloured lights against the sky to bear the elements of form.[25] Fernand Léger was the film-maker who interested Eggeling most among the experimentalists of that day.[26]

The film was completed in Autumn 1924 and shown on 5 November at a private performance at the Gloria Palace to which Eggeling had invited his friends and those who had helped him and shown interest in his work. The gathering included Adolf Behne, Arthur Segal, László Moholy-Nagy, Erich Buchholz (all with wives), El Lissitzky, Ernst Kállai, Alfréd Kemény, and Werner Graeff, with Behne commenting on Eggeling’s new opus for the auditorium.[27]

A day earlier, on 4 November, the film was screened for an invited audience at Verband Deutscher Ingenieuren on the Pariser Platz, and later the same month for an invited circle in Paris when Eggeling paid a short visit to finally meet there Fernand Léger, probably in connection with the premiere screening in the middle of November of Léger’s and Dudley Murphy’s film Ballet mécanique. On 21 April 1925 Symphonie diagonale was certified by the German film censors. It was stated to have a length of 149 metres, which at a projection speed of 18 frames a second corresponds to exactly 7 minutes and 10 seconds.[28]

The reviews appeared in Das Kunstblatt by Paul F. Schmidt[29] and Film-Kurier by B.G. Kawan[30]. His collaborator Erna Niemeyer returned to Weimar before the end of the year.[31]

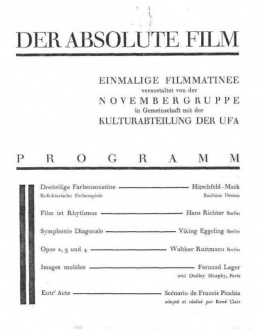

On 3 May 1925, Symphonie diagonale was shown publicly for the first time at a matinée performance jointly arranged by the Novembergruppe and the UFA at the UFA Palast on Kurfürstendamm in Berlin. The program, which was repeated on May 10, was composed as follows (from Kunst der Zeit. Zeitschrift für Kunst und Literatur 3:1/3 (1928): Zehn Jahre Novembergruppe, Berlin, 1928, p 39)[32]:

Film-Matinee, 3.Mai 1925.

Der absolute Film.

Hirschfeld-Mack, Dessau (Bauhaus), Dreiteilige Farbensonatine, Reflektorische Farbenspiele.

Hans Richter, Berlin, Film ist Rhythmus.

Viking Eggeling, Berlin, Symphonie diagonale.

Walther Ruttmann, Berlin, Opus 2, 3 und A.

Fernand Léger und Dudley Murphy, Paris, Images mobiles. [Ballet mécanique.]

Scénario de Francis Picabia, adapté et réalisé par René Clair, Entr'acte.

Eggeling was not present at this performance. He had for some months been a patient at the Norbert-Krankenhaus at Schöneberg in Berlin, and died there on May 19 of syphilis.[33]

- Commentaries on Symphonie diagonale

Ré Soupault gave a detailed account of her collaboration on the film in 1977, printed in the Film as Film exhibition catalogue (1979).[34]

Standish Lawder wrote that "in Diagonal Symphony the emphasis is on objectively analyzed movement rather than expressiveness on the surface patterning of lines into clearly defined movements, controlled by a mechanical, almost metronomic tempo. The spatial complexities and ambiguities of Richter's film are almost non-existent here. Above all, a sober quality of rhythm articulation remains the most pronounced quality of the film."[35]

Gösta Werner in his book Viking Eggeling Diagonalsymfonin (1997) gives an account of the genesis of Symphonie diagonale and of the restoration under his guidance of the copy in the Swedish Film Institute’s Cinemathèque, and presents the hypothesis that Diagonal Symphony is in fact the first movement of a “film symphony” conceived by Eggeling in four parts, four movements as in a symphony: "The thought has been proposed that Diagonal Symphony is only a fragment and that Eggeling intended it as the first movement of a longer film which would then have more palpably justified the designation ‘symphony’. It is just seven minutes long – the normal duration of the first movement of a classical symphony is between five and ten minutes. It has an ingeniously developed imaginative sonata form with a wealth of imitative work. Diagonals and sharp angles play a visually dominant role and contrast with softer visual motifs."[36]

Films

- Horizontal-Vertikal-Messe [Horizontal-vertical Orchestra] (now lost)

- Symphonie diagonale [Diagonal Symphony], 7 min, 1924. [1]

Exhibitions

Major exhibitions including works by Eggeling[37](selection until 1930):

- Cabaret Voltaire, with the Dadaists, Zurich, 1916.

- Galerie Wolfsberg, Zurich, 1919.

- with the Novembergruppe, Berlin, 1922.

- Sammlung Gabrielson Göteborg, Berlin, 1923.

- The International Theatre Exposition, New York, 1926.

- Zehn Jahre Novembergruppe, Berlin, 1928.

Notes

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 17-19

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 20-21

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 35

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 35-36

- ↑ Robbers 2012, pp. 334

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 36-39

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 40

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 40

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 45

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 46

- ↑ Elder 2007, p. 34

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 70

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 46-48

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 75

- ↑ Elder 2007, p. 34

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 49

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 69

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 49

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 49-50

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 50

- ↑ Soupault 1979, p. 76

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 51-52

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 80

- ↑ Soupault 1979, p. 76

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 73-85

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 52

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, pp. 52-53

- ↑ Ahlstrand 2012, p. 219

- ↑ Schmidt 1924

- ↑ Kawan 1924

- ↑ Soupault 1979, p. 76

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 53

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 53

- ↑ Soupault 1979

- ↑ Lawder 1975

- ↑ Ahlstrand 2012, pp. 221-222

- ↑ O'Konor 1971, p. 144

Literature

By Eggeling

- with Arp, Baumann, Giacometti, Henning, Heibig, Janco, Morach, Richter, "Manifest radikaler Künstler Zürich". Probably for the first time read by Hans Richter at the 8th Dada soirée, Saal zur Kaufleuten, Zürich, 9 April 1919. Published in Neue Zürcher Zeitung (4 May 1919), Zweites Sonntagblatt. Repr. in Manifeste und Proklamationen der europäischen Avantgarde (1909-1938), eds. Wolfgang Asholt and Walter Fähnder, Stuttgart/Weimar: J.B. Metzler, 1995, pp 174. (in German)

- "Elvi fejtegetések a mozgóművészetről" [Theoretical Presentation of the Art of Motion], MA, 6:8 (August 1921), Vienna, pp 105-108. [2]. Reprinted in F.I.L.M. - A magyar avant-garde film története és dokumentumai, ed. Peternák Miklós, Budapest: Képzőművészeti kiadó, 1991, pp 62-65. (in Hungarian)

- Compare with: Hans Richter, "Prinzipielles zur Bewegungskunst" [Principles of Movement Art], De Stijl 4:7 (July 1921), pp 109-112. (in German)

- with Raoul Hausmann, "Zweite präsentistische Deklaration. Gerichtet an die internationalen Konstruktivisten", MA 8:5/6 (1923), Vienna, p 5. Deutsches Sonderheft. Reprinted in Louise O'Konor, Viktor Eggeling: 1880-1925: Artist and film-maker: Life and work, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1971, pp 91-92; repr. in Manifeste und Proklamationen der europäischen Avantgarde (1909-1938), eds. Wolfgang Asholt and Walter Fähnder, Stuttgart/Weimar: J.B. Metzler, 1995, pp 300-301. (in German)

- Collected notes

- "Aus dem Nachlass Viking Eggelings", ed. Hans Richter, G 4 (March 1926), Berlin, pp 2-3. (in German)

- "Ur Viking Eggelings efterlämnade papper", in Apropå Eggeling, ed. K. G. Hultén. Stockholm, 1958, p 18. (in Swedish)

- "Anteckningar. Ett urval av Viking Eggelings efterlämnade anteckningar tolkade till svenska från den tyska originaltexten av Louise O'Konor", Konstrevy 43:4 (1967), Stockholm, pp 145-146. (Corrections, see: nos. 5/6, p 260) (in Swedish)

- "Posthumous notes edited and commented", in Louise O'Konor, Viktor Eggeling: 1880-1925: Artist and film-maker: Life and work, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1971, pp 78-85, 92-126, n258-264.

Books and Theses on Eggeling

- O'Konor, Louise (1971). Viktor Eggeling: 1880-1925: Artist and film-maker: Life and work. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. pp. 299.

- Viking Eggeling 1880-1925: modernist och filmpionjär: hans liv och verk, Stockholm: Atlantis, 2006, 173 pp. (in Swedish)

- Gösta Werner, Viking Eggeling Diagonalsymfonin: Spjutspets i återvändsgränd, Lund: Novapress, 1997, 144 pp. (in Swedish)

- Jimmy Pettersson, Viking Eggeling och Diagonalsymfonin: en dematerialisering av konstobjektet, Södertörn University College, 2011. Thesis. (in Swedish) [3]

Book chapters, Papers, Articles on Eggeling

- Tristan Tzara, "Chronique zurichoise, 1915-1919", in Dada Almanach. Im Auftrag des Zentralamts der deutschen Dada-Bewegung, ed. Richard Huelsenbeck, Berlin: Reiss, 1920, pp 10-29.

- Théo van Doesburg, "Abstracte filmbeelding", De Stijl 4:5 (May 1921), pp 71-75. [4]. Reprinted in De Stijl, 2, 1921-1932, Amsterdam, 1968, pp. 54-56.

- Ludwig Hilberseimer, "Bewegungskunst" [Art of Motion], Sozialistische Monatshefte 27:9 (23 May 1921), Berlin, pp 467-468. (in German) [5]. Draft for his later two articles (1922, 1923).

- "Dinamicheskaya zhivopis (Bespredmetnyi kinematograf)", Vesch/Gegenstand/Objet 3 (May 1922), Berlin, pp 17-19. Signed: Liudvig Gilberseimer. (in Russian)

- "Über Bewegungskunst von Eggeling/Richter", MA 8:5/6 (March 1923), pp 13-14. (in German)

- Adolf Behne, "Der Film als Kunstwerk", Sozialistische Monatshefte 27:20 (15 December 1921), Berlin, pp 1116-1118. (in German) [6]

- Ludwig Hilberseimer, "Berlin: Grosse Ausstellung 1922", Sozialistische Monatshefte 28:13 (12 September 1922), p 833. (in German) [7]

- Birger Brinck-E:son, "Linjemusik på vita duken. 'Konstruktiv film', ett intressant experiment av en svensk konstnär", Filmjournalen 5:4 (1923), Stockholm, p 50. (in Swedish)

- Filippo Tommasi Marinetti, "Le futurisme mondial. Manifeste à Paris. Le Futurisme", Revue synthétique illustrée 9 (January 1924), Milan, pp 1-3. (in French)

- Ernst Kállai, "Konstruktivismus", Jahrbuch der jungen Kunst, Bd. 5, Leipzig, 1924, pp 374-384. (in German)

- Schmidt, Paul P. (1924). "Eggelings Kunstfilm". Das Kunstblatt (Berlin) 8: 381 (German).

- Hans Richter, "Die schlecht trainierte Seele", G 3 (June 1924), Berlin, pp 34-35. (in German)

- Kawan, B. G. (22 November 1924). "Abstrakte Filmkunst". Film-Kurier (Berlin) (276): 381 (German). 3. Beiblatt.

- Adolf Behne, "Vicking Eggeling", Die Welt am Abend, Berlin, 23 May 1925; repr. in Kunst der Zeit. Zeitschrift für Kunst und Literatur 3:1/3 (1928): Sonderheft: Zehn Jahre Novembergruppe, Berlin, p 32. (in German)

- Emil Szittya, "Paris am Anfang der neuen Kunst", Das Kunstblatt, vol. 9, Berlin, 1925, pp 115-119. (in German)

- Willi Wolfradt, "Der absolute Film", Das Kunstblatt, vol. 9, Berlin, 1925, pp 187-188. (in German)

- Ludwig Hilberseimer, "Eggeling", Sozialistische Monatshefte, 31:8 (10 August 1925), Berlin, p 517. (in German)

- Hans Richter, "Viking Eggeling", G 4 (March 1926), Berlin, pp 14-16. (in German)

- Rudolf Schneider, "Formspiel durch Kino", Frankfurter Zeitung 511 (12 July 1926), p 1. (in German)

- Lisbeth Stern, "Film", Sozialistische Monatshefte 32:7 (12 July 1926), Berlin, pp 501-505. (in German)

- László Gara, "Az 'abszolút' film", Magyar írás 1 (1926), pp 7-8. Reprinted in F.I.L.M. - A magyar avant-garde film története és dokumentumai, ed. Peternák Miklós, Budapest: Képzőművészeti kiadó, 1991, pp 75-77. (in Hungarian)

- Miklos Ν. Bandi, "La Symphonie diagonale de Vicking Eggeling", Schémas 1 (1927), Paris, pp. 9-19; repr. in Jean Mitry, Le cinéma experimental, Paris: Seghers, 1974, pp 76-84. (in French)

- Nicolas Bandi, "Viking Eggeling 'diagonális szimfóniája'", in F.I.L.M. - A magyar avant-garde film története és dokumentumai, ed. Peternák Miklós, Budapest: Képzőművészeti kiadó, 1991, pp 66-74. (in Hungarian)

- Hans Arp, "Tibiis canere. Zurich 1915-1920", XXe siècle 1 (1938), Paris, pp. 41-44.

- Gösta Morin, "Eggeling, Johan Andreas Christian Friedrich (Fredrik)", in Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, vol. 12, Bonnier: Stockholm, Bonnier, 1949, pp 198-201. (in Swedish)

- [In commemoration of Viking Eggeling], in Viking Eggeling 1880-1925, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, 1950. Catalogue.

- Hans Richter, pp 9-10.

- Hans Arp, pp 10-11.

- Mies van der Rohe, p 11.

- Tristan Tzara, p 11.

- Georg Schmidt, pp 12-15.

- Hans Richter, "Om Viking Eggeling", in Apropå Eggeling, ed. K. G. Hultén. Stockholm, 1958, p 15-17. (in Swedish)

- Louise O'Konor, "Viking Eggelings filmexperiment", in Smalfilm 64. Årsbok för amatör-, industri- och undervisningsfilm, vol. 2, 1963, Stockholm, pp 60-67. (in Swedish)

- Louise O'Konor, "Viking Eggeling och bild-rullarna", Konstrevy, 41:6 (1965), Stockholm, pp 190-194. (in Swedish)

- Louise O'Konor, "The film experiments of Viking Eggeling", Cinema studies 2:2 (June 1966), London, pp 26-31.

- Louise O'Konor, "Två filmpionjärer", Dagens Nyheter, 5 April 1969, Stockholm, p 3. Concerns the film experiments of Walther Ruttmann and Viking Eggeling and Max Butting's score in the Svenska Filminstitutets dokumentationsavdelning, Stockholm, for Ruttmann's film Lichtspiel Opus. (in Swedish)

- Lawder, Standish D. (1975). The Cubist Cinema. New York: New York University Press. Review.

- Soupault, Ré (1979). "Viking Eggeling". Film as Film: Formal Experiment in Film, 1910-1975. London: Arts Council of Great Britain. pp. 75-77.

- Malcolm Le Grice, Abstract Film and Beyond, MIT Press, 1977.

- Malcolm Le Grice, "German Abstract Film in the Twenties", in Film as Film: Formal Experiment in Film, 1910-1975, London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1979, pp 30-36.

- Monika Zurhake, Filmische Realitätsaneignung. Ein Beitrag zur Filmtheorie, mit Analysen von Filmen Viking Eggelings und Hans Richters, Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1982. (in German)

- Júlia Szabó, "Fény és mozgás: Viking Eggeling és a magyar aktivizmus", Filmvilág 3 (1982). (in Hungarian)

- A.L. Rees, "The absolute film", in A History of Experimental Film and Video, London: British Film Institute, 1999, pp 37-40.

- Peter Wollen, "Viking Eggeling", in Paris Hollywood: Writings on Film, Verso, 2002, pp 39-54. [8]

- Elder, R. Bruce (2007). ""Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling: The Dream of Universal Language and the Birth of The Absolute Film"". In Graf, Alexander; Scheunemann, Dietrich. Avant-Garde Film. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi. pp. 3-53.

- A.L. Rees, "Movements in Film, 1912-40", in Film and Video Art, ed. Stuart Comer, London: Tate, 2009, pp 27-45.

- Lars Gustaf Andersson, John Sundholm, Astrid Söderbergh Widding, "Viking Eggeling and the Quest for Universal Language", in A History of Swedish Experimental Film Culture: From Early Animation to Video Art, Stockholm: Mediehistoriskt arkiv, 2010, pp 36-41, n216-217.

- Malcolm Cook, "Visual Music in Film, 1921-1924: Richter, Eggeling, Ruttman", in Music and Modernism, c. 1849-1950, ed. Charlotte de Mille, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011.

- Ahlstrand, Jan Torsten (2012). "Berlin and the Swedish Avant-Garde – GAN, Nell Walden, Viking Eggeling, Axel Olson and Bengt Österblom". In Ørum, Tania; Huang, Ping. A Cultural History of the Avant-Garde in the Nordic Countries 1900-1925. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi. pp. 201-227.

- Robbers, Lutz (2012). Modern Architecture in the Age of Cinema. Mies van der Rohe and the Moving Image. Princeton University. The dissertation elucidates, both historically and theoretically, the association between the architect Mies and the pioneers of abstract film Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling during the early 1920s.

See also

External links

- Bibliography of Works by Viking Eggeling, compiled by Timothy Shipe. [9]

- Viking Eggeling - Musik für die Augen, 9 pages (in German)

- Eggeling at Wikimedia Commons

- Eggeling at Wikipedia

- Eggeling at German Wikipedia