Difference between revisions of "John Cage"

| Line 909: | Line 909: | ||

* Stuart Sanders Smith, "Having Words with John Cage", ''Percussive Notes'' 30:3, Feb 1992, pp 48, 50-52. In this interview Cage talks about ''Hymns and Variations'' and ''Apartment House 1776''; the relationship between composer and performer; Thoreau; ''Empty Words'' and “Mureau”; value judgments; the ''Black Mountain Piece'' and the work of Artaud; and productive ways to engage in improvisation. | * Stuart Sanders Smith, "Having Words with John Cage", ''Percussive Notes'' 30:3, Feb 1992, pp 48, 50-52. In this interview Cage talks about ''Hymns and Variations'' and ''Apartment House 1776''; the relationship between composer and performer; Thoreau; ''Empty Words'' and “Mureau”; value judgments; the ''Black Mountain Piece'' and the work of Artaud; and productive ways to engage in improvisation. | ||

| − | * Ellsworth Snyder, "John Cage Discusses Fluxus", ''Visible Language'' 26:1/2, 1992, pp 59-68. This 1991 interview focuses on Cage’s response to the work of | + | * Ellsworth Snyder, [[Media:Snyder Ellsworth 1992 John Cage Discusses Fluxus.pdf|"John Cage Discusses Fluxus"]] [28 Dec 1991], ''Visible Language'' 26:1/2, 1992, pp 59-68. This 1991 interview focuses on Cage’s response to the work of [[Maciunas]] and the [[Fluxus]] movement, [[Duchamp]] and the [[Dada|Dadaists]], and the reemergence of both movements. He uses both Dada and Fluxus to discuss the nature and purpose of art and what art might mean. [http://visiblelanguagejournal.com/issue/97] |

* Viera Polakovičová, Daniel Matej, "Interview with John Cage", ''Slovak Music'' 2, Bratislava, 1992, pp 43-44. | * Viera Polakovičová, Daniel Matej, "Interview with John Cage", ''Slovak Music'' 2, Bratislava, 1992, pp 43-44. | ||

Revision as of 08:43, 28 August 2020

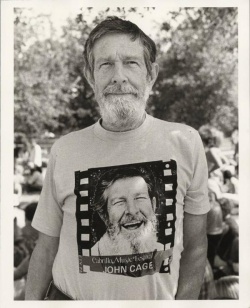

John Cage at the Cabrillo Music Festival, 1977, photographed by Betty Freeman. | |

| Born |

September 5, 1912 Los Angeles, United States |

|---|---|

| Died |

August 12, 1992 (aged 79) New York City, United States |

| Web | UbuWeb Sound, UbuWeb Film, Aaaaarg, Wikipedia, Open Library, Academia.edu |

John Milton Cage, Jr. (1912–1992) was an American composer, music theorist, writer, and artist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde.

Cage is largely credited with the establishment of experimentalism as a style in the 1950s, he was a great inspiration for conceptualist artists in the 1960s, and his music and pedagogical methods were central to the emergence of minimalism in the 1960s and after. Cage's importance extends beyond the field of music, and artists today working in film, literature, dance, theater, and the visual and performance art fields point to Cage as a formative figure. His impact is partially due his collaboration with influential figures in these various fields and partially due to his renown as an author, poet, and visual artist, in addition to his significance as a composer.

Contents

- 1 Life and work

- 2 Chronology

- 3 Compositions

- 3.1 Percussion ensemble

- 3.2 Keyboard

- 3.3 Works for voice

- 3.4 Musique concrète/Electronic music

- 3.5 Variable ensemble

- 3.6 Theater pieces/Simultaneities

- 3.7 Conceptual works

- 3.8 Music box

- 3.9 Radio plays (Hörspiele)

- 3.10 Solo instrumental works (other than keyboard)

- 3.11 Small ensemble

- 3.12 Large ensemble

- 3.13 Text compositions

- 3.14 Visual artworks

- 3.15 Films and Film scores

- 4 Sources and reference material

- 5 Biographical and historical studies

- 6 Other studies (selection)

- 7 Links

Life and work

Based on Sara Haefeli, John Cage: A Research and Information Guide, 2018.

Cage graduated from high school as valedictorian of his class and entered Pomona College, but he dropped out after only a year. Cage travelled to Europe and after returning to the United States started studying composition, first with Richard Buhlig, then with Adolph Weiss; finally Cage studied counterpoint with Arnold Schoenberg at USC and UCLA. Cage’s early music was shaped by his admiration for Schoenberg, but Schoenberg told him that he had no feel for harmony and that without an understanding of harmony he would run up against a wall. Cage replied that he would devote his life to “beating my head against that wall”. Cage repeated this story and a story that Schoenberg called him—not a composer—but an “inventor of genius” so often that much of his reputation and reception as a maverick outsider are based on these accounts.

In the earliest part of his career Cage collaborated with dancers and wrote primarily for percussion ensemble, often employing found objects as musical instruments. In 1940, while he was in his late twenties, he invented the prepared piano and, for his prepared piano piece Sonatas and Interludes, won awards from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Academy of Arts and Letters. In the early 1950s he developed means of composing using chance methods, influencing composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez. In response, Stravinsky sarcastically called the sixties the “Age of Aleatory”. Cage experimented with electronic music ten years before the advent of magnetic tape, and as soon as tape technology was available he created one of the first musique concrète pieces in America, Williams Mix (1951-1953).

Cage didn’t see much distinction between the different art worlds in which he participated. His work in all media was created by the same means of production and motivated by the same creative impulses. Cage often relied on philosophy to bolster his innovations in the arts and to lend legitimacy to his work. During different periods of creativity, Cage drew from different sources for this inspiration. Some of his earliest such encounters were with Southeast Asian philosophy, Indian aesthetics, and the works of Coomaraswamy. As Cage was developing his work with chance operations in the 1950s, he was drawn to East Asian philosophy, especially Zen Buddhism and the teachings of D. T. Suzuki. In his 1957 lecture “Experimental Music,” he described music as “a purposeless play,” which is “an affirmation of life—not an attempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living”. In the 1960s Cage’s work became increasingly political and theatrical and his inspirations were closer to home. Cage was particularly drawn to Thoreau’s Transcendental writings and to the work of Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller. Cage often asserted during this time that his work was meant to teach us how to live in an anarchic utopia: a world, he said, “without a conductor”.

The one word that is most often linked to Cage’s work is indeterminacy. Scholars have recently come to make a distinction between Cage’s use of indeterminacy from the term aleatoric. In aleatoric music, some element of the composition is left to chance or left open to the realization of the performer. This term is most often applied to the work of European composers such as Boulez, Stockhausen, or Lutoslawski, who may indicate extensive passages of notated pitches and rhythms but may leave the coordination of the parts open to chance. Cage’s approach to indeterminacy is different. The most common understanding of the term is applied to works that are indeterminate in their composition, or, in other words, are composed using chance operations. Cage experimented with a number of chance-generating devices (rolling dice, magic squares, etc.) until Christian Wolff gave him a copy of the I Ching in 1951.

The I Ching, or Book of Changes, is an ancient Chinese text that is typically used for divination purposes. Typically, one formulates a question for the I Ching and then tosses three coins a total of six times to create a hexagram, a collection of six straight and/or broken lines stacked on top of one another. There are sixty-four possible hexagrams, and when one is using the I Ching for divination purposes, the results have to be interpreted. Cage used the I Ching to produce numbers (1-64) that he then used to make choices between musical elements that were essentially potential “answers” to compositional “questions.” Cage connected this practice to the Zen Buddhist ideal of removing the ego from his creative work.

Cage’s first fully developed work using the I Ching is Music of Changes for Piano (1951). This work, despite its chance-generated origins, is traditionally notated and each performance of the piece should sound alike. Other works, however, may be traditionally composed but may be indeterminate in their realization. In other words, the resulting sounds will vary from performance to performance. Cage’s most accessible work, Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano, was composed by choice and not chance and yet is somewhat indeterminate in performance, depending on how the performer executes the preparations in the piano. Cage started to move more and more toward openness in every aspect of performance, and in the 1960s he started to write pieces that indicate what is to be done, not necessarily how it is supposed to sound. One such work is Variations IV (1963). Cage’s score is a simple set of instructions: “for any number of players, any sounds or combinations of sounds produced by any means, with or without other activities”.

Cage was fortunate to have the virtuosic pianist David Tudor as his primary musical collaborator and interpreter during the 1950s and 1960s. Tudor was an exceptionally gifted keyboard player and brilliant thinker, and Cage enjoyed creating puzzles for Tudor to solve. These puzzles could be made of exceeding virtuosic challenges (as in Music of Changes), issues of interpretation (as in works with graphic notations, perhaps most notably Solo for Piano), or technological challenges (as in Cartridge Music from 1960, written for various materials inserted into turntable cartridges). For works with indeterminate, open, graphic scores, Tudor was in effect co-composer with Cage, always writing out his own “realizations” to these musical puzzles.

Cage’s most notorious piece, 4‘33” (1952), requires the performer (at the premiere it was Tudor) to sit in silence for four minutes and thirty-three seconds, playing on the well-trained audience’s expectations of high-art music conventions and challenging the boundaries of what could be considered art. But the piece has also had a pedagogical purpose as it has challenged audiences to broaden their listening capabilities and to embrace all sound as potentially musical. Many of Cage’s works continue in this pedagogical vein, challenging audiences not only to listen in new ways but, with Cage’s more anarchic, participatory pieces, to also broaden their social and political philosophies and to start living differently.

For much of his career, Cage toured extensively with the Merce Cunningham Dance Troupe, collaborating with Cunningham and artist Robert Rauschenberg, and much of his time was spent raising money for the Company. As he became increasingly famous in the 1960s, Cage found he had limited time to compose, and as a solution he turned his life into art—publishing and performing his diaries and writing conceptual works without scores but with written sets of instructions of what was to be done, not necessarily what was to be heard. Despite his growing fame, Cage often struggled financially, sometimes taking on work outside the field of music to make ends meet.

While Cage’s work seems antithetical to the philosophy and aesthetic of the American academy, he started partnering with institutions of higher education. From 1956 to 1960 Cage was a faculty member at the New School for Social Research, and in the late 1960s and early 1970s he enjoyed the patronage of the University of Cincinnati; the University of Illinois; the University of California, Davis; and Wesleyan University. These institutions provided some financial stability as well as performance venues and resources.

In the late 1960s Cage was one of the first composers to write music using a computer, and, in collaboration with the groundbreaking computer music composer Lejaren Hiller at the University of Illinois, he composed the massive event HPSCHD (1967-1969). He also used the computer to expedite the time-consumptive process of creating I Ching hexagrams. Several large-scale works followed, including the Europeras 1-5, composed with borrowed source material from the operatic literature. While these works were “Wagnerian” in scope, other works from the same time period—the so-called Number Pieces, for example—are meditative studies, often quite fragmentary.

At the time of his death in 1992, Cage was recognized not only as an important composer but also as a writer, poet, visual artist, and mycologist. Cage’s scores, drawings, lithographs, and watercolors have been included in gallery and museum exhibitions around the world, and a three-volume Catalogue raisonné is currently in publication. Michael Pisaro asserts that “Cage’s impact on modern poetics sometimes seems to be nearly as great as the impact he had on music” and an excerpt from Cage’s “Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) 1965-1967” is included in the anthology American Poetry Since 1950: Innovators and Outsiders (New York, 1993).

Without a doubt, Cage’s most significant publication is Silence, a collection of lectures and writings by the composer that secured his notoriety. Since its release in 1961, Silence, according to Wesleyan University Press, has sold more than half a million copies worldwide. In the context of Cage’s large body of writings, Noël Carroll writes, “Even if he did not think that his music ‘said’ anything, he surrounded it with a great deal of doctrine, freighting his experiments with aesthetic, moral, and political relevance. Much of the writing is polemical, animated by a philosophical conception of music, or, as he would prefer to call it, of the ‘organization of sound’”.

Although the mainstream musical world even today often views Cage as a curiosity, music scholars started to take Cage seriously in the 1960s, despite the fact that by then he had been well respected in contemporary music and art circles for some time. Scholarly attention was sparked by his infamous Darmstadt appearance in 1958, where Cage delivered three provocative lectures outlining his musical philosophy, drawing a sharp divide between American experimentalism and the European avant-garde. One review of the lectures was headlined: “New Music Has Its Cheeky Clown”. Along with Cage’s critics, however, was a passionate group of devotees—at home and abroad—who had a significant impact on Cage’s reception. Cage’s important publication contract with C. F. Peters in 1961 further solidified his reputation.

Chronology

Based on Sara Haefeli, John Cage: A Research and Information Guide, 2018.

- 1912. John Milton Cage born to John Milton Cage and Lucretia Harvey in Los Angeles, California, 5 September.

- 1920-1928. Studies piano with his Aunt Phoebe and Fannie Charles Dillon.

- 1927. Cage wins the Southern California Oratorical Contest at the Hollywood Bowl with his speech “Other People Think.”

- 1928. Graduates from Los Angeles High School as valedictorian.

- 1928-1930. Attends Pomona Collese.

- 1930. Drops out of college and travels to Europe. Begins to compose.

- 1931. Returns to California. Studies composition with Richard Buhlig.

- 1934. Travels to New York on the advice of Henry Cowell to study with Adolph Weiss. Attends Cowell’s ethnomusicology classes at the New School for Social Research.

- 1935. Returns to California. Attends counterpoint classes with Schoenberg, both at the composer’s home and at USC and UCLA. Works odd jobs to make ends meet, including as children’s recreation director and as scientific patent researcher for his father. Gives lectures on modern art to groups of housewives. Marries Xenia Kashvaroff, 7 June.

- 1936. Works as an apprentice to filmmaker Oskar Fischinger. Composes first percussion pieces and first pieces to use rhythmic structures.

- 1937. Accompanist and composer for the UCLA modern dance studio.

- 1938. Joins the faculty at the Cornish School; gives courses on experimental music and dance composition, and accompanies Bonnie Bird’s dance classes. Meets Merce Cunningham. Organizes percussion ensemble using the instruments at the school and instruments he collects and builds out of found objects. 9 December, percussion ensemble concert; maybe the first in North America.

- 1939. Teaches at Mills College, summers 1939-1941. Co-teaches a course with Lou Harrison. Meets composer and critic Virgil Thomson and Peter Yates, critic, author, and host of the avant-garde music series Evenings on the Roof in Los Angeles. Moves to San Francisco; works as recreation leader for the WPA. Premiere of First Construction in Metal in Seattle, 9 December.

- 1940. Premiere of Bacchanale in Seattle, 28 April; first piece for prepared piano to accompany dancer Syvilla Fort.

- 1941. At the invitation of László Moholy-Nagy, moves to Chicago to teach class on experimental music at the Chicago Institute of Design. Cage and Harrison compose their collaborative work Double Music.

- 1942. Arts Club of Chicago percussion ensemble concert. Live broadcast of The City Wears a Slouch Hat with Kenneth Patchen on CBS, 31 May. Moves to New York in the summer. Meets Marcel Duchamp through Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim. Premiere of Credo in US with choreography by Cunningham, 1 August.

- 1943. Museum of Modern Art concert in February. Avoids being drafted by claiming that Xenia is in poor health.

- 1944. Serves as musical director of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company until 1966. Xenia leaves Cage.

- 1945. Moves to New York’s Lower East Side. Attends lectures by D. T. Suzuki at Columbia. Tours with Merce Cunningham Dance Company.

- 1946. Xenia and Cage divorce. Maro Ajemian gives first (incomplete) performance of the Sonatas and Interludes at New York’s Town Hall, 16 April. Meets Indian musician Gita Sarabhai; starts reading Coomaraswamy.

- 1947. Premiere of The Seasons, commission from the Ballet Society in New York, 18 May. Co-founds the art and literary magazine Possibilities with Robert Motherwell, but it folds after one issue.

- 1948. Teaches at Black Mountain College in the summer; meets several significant figures including the scientist Buckminster Fuller, the artist Willem de Kooning and his wife Elaine, sculptor Richard Lippold and his wife Louise (dancer), and the artist Josef Albers. Organizes Satie festival.

- 1949. Premiere of complete Sonatas and Interludes with Maro Ajemian at Carnegie Hall, 12 January. Receives award from the National Academy of Arts and Letters. Receives Guggenheim Fellowship. Travels to Europe with Cunningham. Meets composer Pierre Boulez. Concerts and dance concerts in Paris with Cunningham.

- 1950. Meets Morton Feldman walking out of a New York Philharmonic concert after a performance of Webern’s Symphony, Op. 21. First use of chance operations in Concerto for Prepared Piano. Moves to Monroe Street, New York City. Friend and student Christian Wolff gives Cage an edition of the I Ching. Participates in the Artists Club organized by Robert Motherwell and others; performs at the club “Lecture on Nothing” and “Lecture on Something.” Meets David Tudor, Cage’s primary pianist and collaborator through the mid-1960s.

- 1951. Wins First Prize for Music at the Woodstock Art Film Festival with score for Herbert Matter’s film Works of Colder. Premiere of Imaginary Landscape No. 4 at Columbia University, New York, 10 May.

- 1952. Premiere of Music of Changes, first fully chance-composed piece, 1 January. Premiere of first tape piece Imaginary Landscape No. 5, 18 January. Teaches at Black Mountain College during the summer. Meets Living Theater directors Julian Beck and Judith Malina. Reads Antonin Artaud’s The Theater and Its Double (translated by M. C. Richards). Cage performs Theatre Piece (also known as the Black Mountain Happening) with Cunningham, poets Charles Olson and M. C. Richards, artist Robert Rauschenberg, and Tudor. Premiere of 4′33″ in Woodstock, New York, inspired by Rauschenberg’s all-white paintings (1951), 29 August. Tours with Cunningham Company at colleges and universities in the U.S. during the fall.

- 1953. Premiere of Williams Mix at the University of Illinois, 22 March.

- 1954. Moves to intentional community in Stony Point, NY, with Cunningham, Tudor, Richards, and others. October concert tour with Tudor to Donaueschingen Festival of Contemporary Music; performs new prepared piano duets 31′57.9864″for a Pianist and 34′46.776″for a Pianist; also visits Cologne, Paris, Brussels, Stockholm, Zurich, Milan, and London.

- 1955. Meets Jasper Johns.

- 1956. Serves on the faculty at the New School for Social Research in New York, 1956-1960. Students in these classes include artists, musicians, poets, and composers, including George Brecht, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Toshi Ichiyanagi, Allan Kaprow, and Jackson Mac Low.

- 1958. 25-Year Retrospective Concert at Town Hall, New York, 15 May. Concert includes premiere of Concert for Piano and Orchestra and is recorded and released as a three-LP box set. Gallery exhibition of Cage’s scores at New York’s Stable Gallery timed to coincide with concert. Concertizes in Europe with Tudor and Cunningham, September-March. Darmstadt International Courses for New Music, 2-3 September. Meets conceptual artist and composer Nam June Paik. Delivers his lecture “Indeterminacy” at the Brussels World Fair. Meets Luciano Berio and his wife, Cathy Berberian, in Italy. Composes Fontana Mix at the electronic music studio “Studio di Fonologia” in Milan. Appears five times on the Italian quiz show “Lascia o Raddoppia” answering questions on mushrooms; wins about $8,000. Performs on the programs Amoves, Water Walk, and Sounds of Venice. Begins Variations series, composed between 1958 and 1967.

- 1959. Teaches three courses at the New School: Mushroom Identification, The Music of Virgil Thomson, and Experimental Composition.

- 1960. Signs an exclusive publishing contract with C. F. Peters. Fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University, Middleton, Connecticut. 1960-1961 academic year. Meets philosopher Norman O. Brown.

- 1961. Wesleyan University Press publishes Silence: Lectures and Writings. Premiere of Atlas Eclipticalis in Montreal, 3 August.

- 1962. Founds the New York Mycological Society. Tours Japan with David Tudor, Yoko Ono, and Ichiyanagi, October-December. Composes and premieres 0′00″ in Tokyo, 25 October.

- 1963. Organizes complete performance of Satie’s Vexations at the Cherry Lane Theater in New York, 9-10 September. The performance required a rotating team often pianists and lasted over eighteen hours. Co-founds the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts with Jasper Johns to help support artists including the Cunningham Dance Company.

- 1964. Cage’s father dies on 3 January. New York Philharmonic under the baton of Leonard Bernstein performs Atlas Eclipticalis at Lincoln Center, 6-9 February. Six-month world tour with Cunningham Dance Company.

- 1965. Becomes president of the Cunningham Dance Foundation and director of the Foundation for Contemporary Performing Arts. Meets Marshall McLuhan. Begins the series “Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).”

- 1966. Variations VII performed at the Experiments in Art and Technology “9 Evenings” at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, 13-23 October.

- 1967. Composer in Residence, University of Cincinnati. Associate at the Center for Advanced Study, University of Illinois 1967-1969; collaborates with Lejaren Hiller on computer-assisted composition. Musicircus premiere in the Stock Pavilion at the University of Illinois, 17 November. Publishes A Year From Monday. Wendell Berry introduces him to the journals of H. D. Thoreau, whose writings become an important influence on Cage’s anarchic political philosophy and are source material for later compositions.

- 1968. Elected member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters of the American Academy. Receives Thorne Music Grant. Performance of Reunion with Duchamp in Toronto, 5 March. Both Cage’s mother and Duchamp die in October.

- 1969. Premiere of HPSCHD, computer piece started in 1967 with collaborators Hiller, Ron Nameth, and Calvin Sumsion, 16 May. Creates visual artwork Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel with Sumsion. Artist in Residence at the University of California, Davis. “Mewantemooseicday” performance including 33⅓ and music of Satie, 21 November. Publishes Notations with Alison Knowles.

- 1970. Advanced Fellow at Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University. Writes “36 Mesostics Re and Not Re Marcel Duchamp.”

- 1971. Writes “62 Mesostics re Merce Cunningham.” Starts reading Mao Tse-tung. Writes “Mureau.”

- 1972. Writes Mushroom Book with Lois Long and Alexander Smith. European tour with Tudor. Moves to Manhattan apartment on the corner of West 18th Street and Sixth Avenue.

- 1973. Publishes M: Writings ’67-’72.

- 1974. Starts work on Etudes Australes and Empty Words. Premiere of Score (40 Drawings by Thoreau) and 23 Parts in Saint Paul, MN, 28 September.

- 1975. Premiere of Child of Tree in Detroit, 8 March.

- 1976. U.S. Bicentennial celebrations include premiere of Lecture on the Weather in Toronto and premiere of Renga and Apartment House 1776 in Boston with Seiji Ozawa.

- 1977. Adopts a macrobiotic diet on the advice of Yoko Ono.

- 1978. Print work at Crown Point Press in Oakland, California in January. Returns almost every year for a week or two for fifteen years. Publishes Writing through Finnegans Wake. Performance of Alia ricerca del silenzio perduto: II Treno for prepared train in Bologna, Italy, 26-28 June.

- 1979. Works at IRCAM with David Fullerman. Publishes Empty Words: Writings ’73-’78. Premiere of Roaratorio, an Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake in Donaueschingen, 20 October; begins long association with Klaus Schoning and the Electronic Music Studio at WDR in Cologne.

- 1980. Writes Third and Fourth Writings through Finnegans Wake.

- 1981. Premiere of Dance/4 Orchestras San Juan Bautista, CA, 22 August. Night-long performance of Empty Words at Christ Cathedral Church in Hartford, CT, 25-26 September; broadcast on KBOO. Premiere of Thirty Pieces for Five Orchestras in Pont-a-Mousson, France, 22 November.

- 1982. Publishes Composition in Retrospect. Whitney Museum of American Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art has special exhibits of Cage’s scores and prints. Publishes Mud Book with Long. Awarded Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in Paris. A House Full of Music performed by about 800 music-school children in Bremen, Germany, 10 May. Broadcast of James Joyce, Marcel Duchamp, Erik Satie: An Alphabet on WDR, Cologne, 6 July. Broadcast of Fifteen Domestic Minutes on National Public Radio, 15 September.

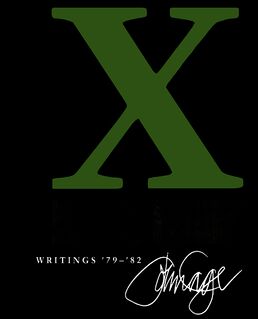

- 1983. Inducted as a member of the Percussive Arts Hall of Fame. Publishes X: Writings ’78-’82. Begins series of Ryoanji drawings and compositions.

- 1984. Starts using IBM personal computer with assistance from Andrew Culver and Jim Rosenberg. Writes “Writing Through Howl,” first computer-assisted mesostic. Starts work on “The First Meeting of the Satie Society.”

- 1985. Premiere of ASLSP in College Park, MD, 14 July.

- 1986. Performance of Ryoanji (all versions simultaneously) at New Music American festival in Houston, 5 April. Receives honorary Doctor of All the Arts from California Institute of the Arts. Premiere of Etcetera 2/4 Orchestras in Tokyo, 8 December.

- 1987. Premiere of Essay, 18 readings, 36 loudspeakers, 10 March. International 75th birthday celebrations, including week-long events at Los Angeles Festival. Begins Number Pieces with Two for flute and piano. Premiere of Europeras 1 & 2 in Frankfurt, 12 December.

- 1988. Creates New River Watercolors at Mountain Lake Workshop, Virginia, 3-8 April. Norton Lectures at Harvard, I-VI, during the 1988-1989 academic year.

- 1989. Inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Receives Kyoto Prize in Creative Arts and Moral Sciences. Performance of “Dancers on a Plane: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns” in London and Liverpool. Creates Steps paintings at Mountain Lake Workshop, Virginia.

- 1990. Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. exhibits New River Watercolors. Creates River Rocks Smoke at Mountain Lake Workshop, Virginia, April. Premiere of 14 for piano and orchestra in Zurich, 12 May. Premiere of Europeras 3 & 4, Almeida Music Festival in London, 17 June. Starts work on “Rolywholyover: A Circus” for Los Angeles Museum of Modern Art. Scottish National Orchestra produces a week of Cage music. Premiere of Scottish Circus, 20 September during Musica Nova festival.

- 1991. Premiere of Europera 5 in Buffalo, NY, 18 April. Premiere of Four3/Beach Birds collaboration with Cunningham in Zurich, 20 June; Zurich June Festival dedicated to Cage and James Joyce.

- 1992. 80th birthday celebrations, including Stanford University, Northwestern University, Frankfurt Fest, MoMA Summergarden Series in New York. Writes new orchestral works for the Hessischer Rundfunk in Frankfurt, Österreichische Rundfunk in Graz, and American Composers Orchestra in New York. Completes work on film with Henning Lohner, One11. Prepares Rolywholyover: A Circus for Museum for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Dies at his home in New York City, 12 August.

Compositions

Unpublished works are generally not included. See the New York Public Library John Cage Music Manuscript Collection for unpublished works information. There are a number of “one-off" events that are significant but are not published; only the most important are listed here. Based on Sara Haefeli, John Cage: A Research and Information Guide, 2018.

Percussion ensemble

Solo percussion works included in Solo Instrumental Works section.

- Quartet, 1935 (4 percussionists)

- Trio, 1936 (3 percussionists; Cage used mvmt. III. Waltz in his later composition Amores, 1943)

- First Construction (in Metal), 1939 (6 percussionists)

- Dance Music for Elfrid Ide, 1940 (2-6 percussionists, piano)

- Second Construction, 1940 (4 percussionists)

- Fads and Fancies in the Academy, 1940 (piano, 4 percussionists)

- Living Room Music (Stein), 1940 (percussion and speech quartet)

- Imaginary Landscape No. 2, 1940 (percussion quartet; withdrawn, unpublished)

- Double Music, 1941 (4 percussionists, collaboration with Lou Harrison)

- Third Construction, 1941 (4 percussionists)

- Imaginary Landscape No. 3, 1942 (6 percussionists)

- Credo in Us, 1942 (4 percussionists; including piano, radio/turntable)

- Forever and Sunsmell (e. e. cummings), 1942 (1 voice, 2 percussionists)

- Imaginary Landscape No. 2 (March No. 1), 1942 (5 percussionists; premiered as Imaginary Landscape No. 4, but Cage renamed it)

- Amores, 1943 (prepared piano, 3 percussionists)

- She Is Asleep (I. Quartet), 1943 (4 percussionists; 12 tom-toms; voice and prepared piano in 1943)

- Duet for Cymbal, 1964 (2 percussionists)

- But what about the noise of crumpling paper which he used to do in order to paint the series of “Papiers froissés" or tearing up paper to make “Papiers déchirés"? Arp was stimulated by water (sea, lake and flowing waters like rivers), forests, 1985 (percussion ensemble)

- Three2, 1991 (3 percussionists)

- Six, 1991 (6 percussionists)

- Four4, 1991 (4 percussionists)

Keyboard

Prepared piano (solo)

- Bacchanale, 1940

- Totem Ancestor, 1942

- And the Earth shall Bear Again, 1942

- In the Name of the Holocaust, 1942

- Primitive, 1942

- Our Spring Will Come, 1943

- A Room, 1943 (piano or prepared piano)

- She Is Asleep, 1943 (voice and prepared piano)

- Tossed as it is Untroubled (Meditation), 1943

- The Perilous Night, 1944

- Prelude for Meditation, 1944

- Root of an Unfocus, 1944

- Spontaneous Earth, 1944

- Triple-Paced (Second Version), 1944

- The Unavailable Memory of, 1944

- A Valentine Out of Season, 1944

- Daughters of the Lonesome Isle, 1945

- Mysterious Adventure, 1945

- Music for Marcel Duchamp, 1947

- Sonatas and Interludes, 1948

- Two Pastorales, 1952

- 31‘57.9864" for a Pianist, 1954 (for solo prepared piano, to be used in whole or in part to provide a solo or ensemble for any combination of pianists, string players, and percussionists)

Prepared piano (duo)

- A Book of Music, 1944

- Three Dances, 1945

Prepared piano and orchestra

- Concerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra, 1951 (prepared piano, Fl/Picc, Ob, Ca, 2 Cls, Bsn, Hrn, Tpt, 2 Tbns, Tba, 4 Perc, Hp, Pf/Cel, Str 5)

Piano (solo)

- Three Easy Pieces, 1933

- Two Pieces for Piano, 1935 (revised in 1974)

- Quest, 1935

- Metamorphosis, 1938

- Jazz Study, 1942

- Ad Lib, 1943

- Chess Pieces, 1943 (also as visual art work; this composition was originally conceived as an ink-and-gouache on Masonite painting)

- Soliloquy, 1945

- Ophelia, 1946

- Two Pieces, 1946

- The Seasons Ballet in One Act, 1947 (large ensemble version in 1947)

- Dream, 1948

- In a Landscape, 1948 (also version for harp)

- Haikus, 1951

- Music of Changes, 1951

- Waiting, 1952

- Seven Haiku, 1952

- For M.C. and D.T., 1952

- Music for Piano 1, 1952

- 4‘33", 1952 (revised in 1960)

- Music for Piano 2, 1953

- Music for Piano 3, 1953

- Music for Piano 4-19, 1953 (for any number of pianos)

- Music for Piano 20, 1953

- 34‘46.776" for a Pianist, 1954 (for solo piano, to be used in whole or in part to provide a solo or ensemble for any combination of pianists, string players, and percussionists)

- Music for Piano 21-36/37-52, 1955 (for any number of pianos)

- Music for Piano 53-68, 1956 (for any number of pianos)

- Music for Piano 69-84, 1956 (for any number of pianos)

- For Paul Taylor and Anita Dencks, 1957

- Winter Music, 1957 (1-20 pianos)

- TV Köln, 1958

- Music Walk, 1958 (1 or more pianists, with radio and/or recordings)

- Music for Piano 85, 1962 (piano and electronics, unpublished)

- Electronic Music for Piano, 1965 (piano and electronics)

- Cheap Imitation, 1969 (orchestrated version in 1972, violin version in 1977)

- Etudes Australes, 1975

- Etudes Boreales I-IV (for solo piano), 1978 (cello version in 1978)

- Perpetual Tango, 1984

- ASLSP, 1985

- One, 1987

- Swinging, 1989 (alternate title: Sports)

- One2, 1989

- The Beatles 1962-1970, 1990 (piano and tape)

- One5, 1990

Piano (two or more)

- Experiences No. 1, 1945 (2 pianos)

- Two2, 1989 (2 pianos)

Piano and orchestra

- Concert for Piano and Orchestra, 1958 (any solo or combination of Pf, Fl[Picc, AF], Cl, Bs[BarSax], Tpt, Tbn, Tba, 3 Vln, 2 Vla, Vc, and Cb, with optional conductor)

Toy piano

- Suite for Toy Piano, 1948 (toy piano or piano)

- Music for Amplified Toy Pianos, 1960 (1 or more toy pianos)

Carillon

- Music for Carillon No. 1, 1952

- Music for Carillon No. 2, 1954

- Music for Carillon No. 3, 1954

- Music for Carillon No. 4, 1961 (carillon and electronics)

- Music for Carillon No. 5, 1967

Organ

- Some of The Harmony of Maine, 1978 (organ and assistants)

- Souvenir, 1983

- Organ2/ASLSP, 1987

Works for voice

Solo voice

- Greek Ode, 1932 (Aeschylus; voice and piano)

- Three Songs, 1933 (Stein; voice and piano)

- Five Songs for Contralto, 1938 (e. e. cummings; contralto and piano)

- Forever and Sunsmell, 1942 (e. e. cummings; solo voice and two percussionists)

- The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs, 1942 (James Joyce; solo voice and closed piano)

- She Is Asleep, 1943 (voice and prepared piano, prepared piano version in 1943)

- Four Walls, 1944 (Cunningham; voice and piano)

- Experiences No. 2, 1948 (e. e. cummings; solo voice)

- A Flower, 1950 (for voice and closed piano)

- Aria, 1958 (solo voice)

- Solo for Voice 1, 1958 (solo voice)

- Solo for Voice 2, 1960 (1 or more voices)

- Song Books, 1970 (solo voice; each solo belongs to one of the following categories: 1. Song; 2. Song using electronics; 3. Theatre; 4. Theatre using electronics)

- Nowth upon Nacht, 1984 (Joyce; solo voice and piano)

- Eight Whiskus, 1984 (C. Mann; solo voice; solo violin version in 1985)

- Mirakus2, 1984 (solo voice)

- Selkus2, 1984 (solo low voice; notated in the alto clef)

- Sonnekus2, 1985 (solo voice)

- Four Solos for Voice (93-96), 1988 (solo 93 is for soprano, solo 94 for mezzo-soprano, solo 95 for tenor, and solo 96 for bass)

Multiple voices

- Hymns and Variations, 1979 (12 amplified voices)

- Litany for the Whale, 1980 (2 voices)

- Ear for EAR, 1983 (vocal ensemble)

- Four2, 1990 (SATB choir)

Musique concrète/Electronic music

- Imaginary Landscape No. 1, 1939 (4 percussionists with 2 variable-speed turntables, frequency recordings, muted piano, cymbal)

- Imaginary Landscape No. 4, 1951 (12 radios)

- Imaginary Landscape No. 5, 1952 (any 42 recordings, score to be realized as a magnetic tape)

- Williams Mix, 1952 (8 1-track tapes, 4 2-track tapes)

- Speech 1955, 1955 (5 radios, newsreader)

- Radio Music, 1956 (1-8 radios)

- Fontana Mix, 1958 (tape)

- WBAI, 1960 (auxiliary score for operator of machines; for performance with Cage’s lecture “Where Are We Going? and What Are We Doing?" or instrumental performance of any parts of Concert for Piano and Orchestra involving magnetic tape [Fontana Mix], recordings, radios, etc.)

- Music for The Marrying Maiden, 1960 (tape, written for play by Jackson Mac Low)

- Cartridge Music, 1960 (live electronics)

- Rozart Mix, 1965 (tape)

- Variations V, 1965 (any number of performers, photo-electric cells, electronic sound sources)

- Variations VI, 1966 (any number of performers, photo-electric cells, electronic sound sources)

- Variations VII, 1966 (any number of performers, photo-electric cells, electronic sound sources; notated in 1972)

- Reunion, 1968 (specially constructed electronic chessboard and two players; realization of 0‘00", and subtitled 0‘00" No. 2)

- 33⅓, 1969 (records and at least 12 turntables to be played by the audience)

- Bird Cage, 1972 (12 tapes)

- Lecture on the Weather, 1975 (12 amplified voices—preferably American men who have become Canadian citizens—tapes, film)

- Telephones and Birds, 1977 (3 performers, telephone announcements, and recordings of bird songs)

- 49 Waltzes for the Five Boroughs, 1977 (1 or more performers, 1 or more listeners, 1 or more record makers)

- Address, 1977 (phonodiscs and 12 turntables to be operated by the audience, 5 performers using cassette machines and electric bell)

- A Dip in the Lake: Ten Quicksteps, Sixty-One Waltzes and Fifty-Six Marches for Chicago and Vicinity, 1978 (1 or more performers, 1 or more listeners, 1 or more record makers)

- Improvisation III, 1980 (1 or more performers with cassette recorders)

- Improvisation IV, 1982 (for 3 cassette players)

- Essay, 1986 (alternate title: Stratified Essay or Voiceless Essay, tape)

- Five Hanau Silence, 1991 (tape of environmental sounds of Hanau)

Variable ensemble

- Variations I, 1958 (any number of players, any means)

- Variations II, 1961 (any number of players, any means)

- Variations III, 1963 (any number of people performing any actions)

- Ryoanji, 1985 (for any solo or combination of voice, flute, oboe, trombone, double bass ad libitum with tape, and obbligato percussionist or any 20 instruments)

- Five, 1988 (any 5 instruments and/or voices)

Theater pieces/Simultaneities

- Water Music, 1952 (piano, radio, whistles, water containers, and a deck of cards)

- Black Mountain Piece, 1952 (alternative title: Black Mountain Happening, Black Mountain Event; indeterminate number of performers, multimedia event; unpublished)

- Water Walk, 1959 (solo television performer with 1-track tape, with large number of properties, mostly related to water)

- Sounds of Venice, 1959 (solo television performer with tape and various properties)

- Theatre Piece, 1960 (1-8 performers—musicians, dancers, singers, etc.)

- Musicircus, 1967 (mixed-media event, any number of performers)

- HPSCHD, 1969 (1-7 amplified harpsichords, 1-51 tapes, mixed-media; with Lejaren Hiller)

- Les Chants de Maldoror pulvérisés par l’assistance même, 1971 (text by Lautréamont; for French-speaking audience of not more than 200)

- Apartment House 1776, 1976 (mixed-media event, indeterminate instrumentation)

- Renga, 1976 (78 parts, for any instruments and/or voices)

- Alla ricerca del silenzio perduto (Il treno), 1977 (for “prepared train"; any number of performers)

- A House Full of Music, 1982 (a musicircus performed by music students)

- Musicircus for Children, 1984

- Europeras 1 & 2, 1987 (opera; any number of voices, chamber orchestra, tape, and organ)

- Sculptures musicales, 1989 (any sounds)

- Europeras 3 & 4, 1990 (opera; Europera 3: 6 voices, 2 pianos, 6 gramophone operators, tape; Europera 4: 2 voices, piano, turntable)

- Scottish Circus, 1990 (musicircus based on Scottish traditional music)

- Europera 5, 1991 (opera; 2 voices, piano, tape)

Conceptual works

These pieces do not have traditional or graphic notations but written instructions.

- 4‘33", 1952

- 0‘00" (4‘33" no. 2), 1962 (solo for any performer with amplification)

- Variations IV, 1963 (any number of players, any means, any media)

- Musicircus and variations on the Musicircus, 1967

- Child of Tree, 1975

- Branches, 1976

- Variations VIII, 1978 (score begins with “no music no recordings")

- One3 = 4‘33" (0‘0") + 𝄞, 1989 (solo performer, unpublished)

Music box

- Extended Lullaby, 1991

Radio plays (Hörspiele)

- The City Wears a Slouch Hat, 1942 (Patchen; for 4 percussionists and sound effects)

- Roaratorio, an Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake, 1979 (published as ___, __ _____ circus on _________)

- Paragraphs of Fresh Air, 1979 (radio event for voice and four instrumentalists also operating tapes, cassettes, phonodiscs or microphones, and telephone; unpublished)

- Fifteen Domestic Minutes, 1982 (one male and one female speaker, texts from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake)

- Klassik Nach Wunsch, 1982

- James Joyce, Marcel Duchamp, Erik Satie: An Alphabet, 1982

- HMCIEX, 1984

- Empty Mind, 1987

Solo instrumental works (other than keyboard)

- Sonata for Clarinet, 1933 (solo clarinet)

- 59 ½" for a String Player, 1953 (for any four-stringed instrument)

- 26‘ 1.1499" for a String Player, 1955 (for any four-stringed instrument)

- 27‘ 10.554" for a Percussionist, 1956 (1 percussionist)

- Concert for Piano and Orchestra, 1958 (any of the parts may be played as a solo; flute, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, trombone, tuba, violin, viola, cello, or bass; the “Solo for Sliding Trombone" is often performed)

- Child of Tree, 1975 (1 percussionist, amplified plant materials)

- Branches, 1976 (1 percussionist, amplified plant materials)

- Chorals for solo violin, 1978

- Etudes Boreales I-IV (for solo cello), 1978 (piano version in 1978)

- Eight Whiskus, for solo violin, 1985 (solo voice version in 1984)

- Ryoanji, 1985 (any solo from or combination of voice, flute, oboe, trombone, double bass ad libitum with tape, and obbligato percussionist)

- Freeman Etudes I-XVI, 1990 (for solo violin; books 1 and 2 composed between 1977 and 1980)

- Freeman Etudes XVII-XXXII, 1990 (for solo violin; books 3 and 4 composed between 1977. and 1980, returned to in 1989 and completed in 1990)

- ¢Composed Improvisation No. 1 (for Steinberger Bass Guitar), 1990

- ¢Composed Improvisation No. 2 (for Snare Drum Alone), 1990

- ¢Composed Improvisation No. 3 (for One-Sided Drums With or Without Jangles), 1990

- One4, 1990 (solo percussion)

- One6, 1990 (violin)

- One7, 1990 (any instrument)

- One8, 1991 (cello)

- One9, 1991 (shō)

- One10, 1992 (violin)

Small ensemble

- Sonata for Two Voices, 1933 (any two or more instruments)

- Composition for Three Voices, 1934 (any three or more instruments)

- Solo with Obbligato Accompaniment of Two Voices in Canon, and Six Short Inventions on the Subjects of the Solo, 1934 (3 or more instruments; revised in 1963; arrangement for 7 instruments in 1958)

- Three Pieces for Flute Duet, 1935

- Music for “Marriage at the Eiffel Tower", 1936 (libretto by Cocteau; piano[s] and percussion; collaboration with Henry Cowell, George Frederick McKay, Silvestre Revueltas, and Amadeo Roldán)

- Music for Wind Instruments, 1938 (wind quintet)

- Four Dances, 1943 (1 voice, prepared piano, percussion)

- Party Pieces (“Sonorous and Exquisite Corpses"), 1945 (flute, clarinet, bassoon, horn, and piano; collaboration with Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, and Virgil Thomson)

- Prelude for Six Instruments, 1946 (flute, bassoon, trumpet, piano, violin, and cello)

- Nocturne, 1947 (violin and piano)

- String Quartet in Four Parts, 1950 (string quartet)

- Six Melodies, 1950 (violin and keyboard)

- Sixteen Dances, 1951 (flute, trumpet, 4 percussionists, piano, violin, and cello)

- Cheap Imitation, 1977 (solo violin; piano version in 1969, orchestrated version in 1972)

- Inlets, 1977 (three players of water-filled conch shells and one conch player using circular breathing and the sound of fire)

- Postcard from Heaven, 1982 (1-20 harps)

- Thirty Pieces for String Quartet, 1983

- Haikai, 1984 (flute and zoomoozophone; Dean Drummond invented the zoomoozo-phone, made from 129 aluminum tubes tuned to a 31-note per octave scale in just intonation)

- Music for..., 1984 (variable chamber ensemble; parts available for voice, flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, trumpet, 4 percussionists, 2 pianos, 2 violins, viola, and cello; revised in 1987)

- Improvisation A + B, 1984 (voice, clarinet, trombone, percussion, and cello)

- Ryoanji, 1985

- Thirteen Harmonies, 1986 (violin and piano)

- Hymnkus, 1986 (any solo or chamber ensemble of voice, alto flute, flute, clarinet, alto and tenor saxophones, bassoon, trombone, 2 percussionists, accordion, 2 pianos, violin, and cello)

- Haikai, 1986 (gamelan ensemble)

- Two, 1987 (flute, piano)

- Seven, 1988 (flute, clarinet, percussion, piano, violin, viola, and cello)

- Four, 1989 (string quartet)

- Three, 1989 (3 recorders of various ranges)

- Seven2, 1990 (bass flute, bass clarinet, bass trombone, 2 percussionists, cello, bass)

- Eight, 1991 (flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, tenor trombone, and tuba)

- Five2, 1991 (English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, timpani)

- Four3, 1991 (4 players on 1 or 2 pianos, rainsticks, violin and oscillator)

- Two3, 1991 (shō, five conch shells played by one player)

- Two4, 1991 (violin, piano or shō)

- Five3, 1991 (trombone, string quartet)

- Five4, 1991 (soprano saxophone, alto saxophone, 3 percussionists)

- Five5, 1991 (flute, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, percussion)

- Four5, 1991 (four saxophones)

- Ten, 1991 (flute, oboe, clarinet, trombone, percussion, string quartet, piano)

- Two5, 1991 (tenor trombone, piano)

- Four6, 1992 (4 performers)

- Two6, 1992 (violin, piano)

Large ensemble

- The Seasons (for Orchestra), 1947 (2.Picc.2.Ca.2.ClEb.BCl.2—2.2.2.0—Timp—Perc—Pf/Cel—Hp—Str 8.6.4.3.2; solo piano version in 1947)

- Atlas Eclipticalis, 1962 (orchestra; any combination of instruments drawn from 3 Fl[AFl, Picc, ad lib.], 3 Ob[Ca, Sax, ad lib.], 3 Cl[Bcl or Cbcl, ad lib.] 3 Bsn[Cbsn, ad lib.], 5 Hrn, 3 Tpt, 3 Tbn[Tenor, Bass, ad lib.], 3 Tba, 3 Timp, 9 [using miscellaneous unspecified nonpitched instruments], 3 Hp, Str 12.12.9.9.3, may be performed with Winter Music)

- Cheap Imitation (variable large ensemble), 1972 (versions available for 24, 59, and 95 players; piano version in 1969, violin version in 1977)

- Etcetera, 1973 (Materials A, Al, A2, B, Dl, B2 for orchestral performance with and without 3 conductors, and a tape recording C of the environment in which the materials were written; 1.1.1.1—1.1.0.1—4Perc—2Pf—Str 1.1.1.1.0; substitutions, additions, and subtractions may be made; in addition to instrument[s], each player uses a nonresonant cardboard box, preferably a transfer file box)

- Quartets I, V, and VI, 1976 (concert band and 12 amplified voices; this work is entitled Quartets because only 4 instruments play at any given time)

- Quartets I-VIII, 1976 (for orchestra of 24: 1.2.1.2—2.0.0.0 Str 5.4.3.3.1)

- Quartets I-VIII, 1976 (for orchestra of 41: 2.2.2.2—2.2.0.0 Str 8.7.6.5.3)

- Quartets I-VIII, 1976 (for orchestra of 93: 3.4[Ca].4[ClEb, BCl].3—6.4.3.1—Str 18.15.12.11.9)

- Thirty Pieces for Five Orchestras, 1981 (3[Picc, AFl].3.3.3—5.5.6 [2TTbn, 2BTbn, 2CbTbn]. 0—Timp—2 Perc—Pf—Str 14.12.10.8.6)

- Dance/4 Orchestras, 1982 (3.3.3.3—4.3.3.1—Timp—3 Perc—Hp—Pf—Str 8.8.6.5.3)

- A Collection of Rocks, 1984 (for double chorus and orchestra without conductor; SSAATTBB—2.2.2.ASax.TSax.BarSax.2—2.2.2.0—Str[no Vla or Db])

- Etcetera 2/4 Orchestras, 1985 (orchestra and tape; 3[Picc, AFl].3[Ca].3[BCl].3[Cbsn]—4.3.3.1—3Perc—Pf—Hp—Str 12.12.8.6.4—Tape)

- Ryoanji, 1985 (any 20 instruments)

- 1O1, 1988 (orchestra: 4[Picc, AFl].4[Ca].4[BCl].4[Cbsn]—6.4.3.1—Timp—4Perc—Pf—Hp—Str 18.16.12.12.8)

- Twenty-Three, 1988 (string orchestra: 13Vln.5Vla.5Vc)

- Fourteen, 1990 (1[Picc].BFl.0.1.BCl.0—1.1.0.0—2Perc—Pf—Str 1.1.1.1.1)

- 108, 1991 (Vc or Shō solo—4[Picc, AFl).5[2Ca].5[2BCl].5[2Cbsn]—7.5.5.1—5Perc—Str 18.16.12.12.8)

- 103, 1991 (orchestra: 4[Picc, AFl].4[2Ca].4[BCl].4[Cbsn]—4.4.4.1—2Timp—2Perc—Str)

- Twenty-Eight, 1991 (wind ensemble [or orchestra]; 4[AFl].4[Ca].4.4[Cbsn]—4.4.3.1)

- Twenty-Six, 1991 (26 violins or orchestra)

- Twenty-Nine, 1991 (4[AFl].4[Ca].4.4[Cbsn]—4.4.3.1—2Timp—2Perc—Pf—Str 14.12.10.8.6)

- Eighty, 1992 (orchestra: 7AFl.7Ca.7Cl—7Tpt—Str 16.14.12.10.0)

- Sixty-Eight, 1992 (orchestra: 3AFl.3Ca.5Cl—5Tpt—4Perc—2Pf—Str 14.12.10.10.0)

- Fifty-Eight, 1992 (wind ensemble: 10[3Picc, 3AFl].7[3Ca].7[3BCl].12Sax [3SSax, 3ASax, 3TSax, 3BarSax].7[3Cbsn]—4.4.4.3)

- Seventy-Four, 1992 (orchestra: 3.3.3.3—4.3.3.1—2Perc—2Pf—Hp—Str 14.l0.8.8.6)

- Thirteen, 1992 (chamber ensemble: 1.1.1.1—1.1.0.0—Timp—2Xyl—Str 1.1.1.1.0)

- Sixteen, 1992 (chamber ensemble: for 1.1.1.1—Hn.Tpt.Tbn.BTbn—Pf—Timp—Xyl—Str 1.1.1.1.1; unpublished; perhaps original version of Thirteen)

Text compositions

Rob Haskins has called this group of writings “text compositions". These poems and lectures use the same compositional procedures as Cage’s music (rhythmic structures, chance processes, use of source materials) and are meant for performance—by Cage or by others. Nyman writes: “In his writings Cage has constantly blurred the distinctions between words for reading (to oneself) and (the same) words for performing (in front of an audience)" and Haskins writes that Cage’s compositional lists “should probably also include many of the texts that he intended for public performance". Included here are essays and poems that were composed and that Cage “performed." Many of these text compositions are published in collections. The largest collections are Silence, A Year From Monday, M: Writings, Empty Words, X: Writings, John Cage: Writer, Musicage, John Cage: Composed in America, and Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).

- "The Future of Music: Credo", 1938?

- "Lecture on Nothing", 1950

- "Lecture on Something", 1951

- "Juilliard Lecture", 1952

- "45‘ for a Speaker", 1954

- "Composition as Process 1. Changes", 1958

- "Composition as Process 2. Indeterminacy", 1958

- "Composition as Process 3. Communication", 1958

- "Lecture on Commitment", 1961

- "Where Are We Going? and What Are We Doing?", 1961

- "26 Statements re Duchamp", 1963

- "Jasper Johns: Stories and Ideas", 1964

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse)", 1965

- "How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run", 1965

- "Talk I", 1965

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) Continued 1966", 1966

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) Continued 1967", 1967

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) Continued 1968 (Revised)", 1968

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) Continued 1969", 1969

- "36 Mesostics Re and Not Re Marcel Duchamp", 1970

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) Continued 1970-71", 1971

- "62 Mesostics re Merce Cunningham", 1971

- "Mureau", 1972

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) Continued 1971-72", 1972

- Empty Words, 1974

- Score (40 Drawings by Thoreau) and 23 Parts, 1974 (any instruments and/or voices; twelve haiku followed by a recording of the dawn at Stony Point, New York, August 6, 1974)

- "Where Are We Eating? and What Are We Eating? (38 Variations on a Theme by Alison Knowles)", 1975

- "Letters to Erik Satie", 1978 (voice and tape) [unpublished]

- "Themes and Variations", 1980

- "Composition in Retrospect", 1981

- "Muoyce (Writing for the Fifth Time through Finnegans Wake)", 1982

- "Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) Continued 1973-82", 1982

- "Mushrooms et Variationes", 1983 [in The Guests Go in to Supper, San Francisco: Burning Books, 1986, pp 15-19]

- "The First Meeting of the Satie Society", 1985 [unpublished]

- "Writings through the Essay: On the Duty of Civil Disobedience", 1985

- "Tokyo Lecture and Three Mesostics", 1986

- "Time (One Autoku)", 1988

- "Anarchy", 1988

- "Art Is Either a Complaint or Do Something Else", 1988

- "Sports", 1989

- "Overpopulation and Art", 1991

- "Muoyce II (Writing through Ulysses)", 1992 (alternate title: “Writing through Ulysses: Muoyce II") [unpublished]

Visual artworks

- Chess Pieces, 1943

- Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel, with C. Sumsion, 1969

- Series re: Morris Graves, 1974

- 30 Drawings by Thoreau, 1974

- Score without Parts (40 Drawings by Thoreau), 1978

- Seven-day Diary (Not Knowing), 1978

- 17 Drawings by Thoreau, 1978

- Signals, 1978

- Changes and Disappearances, 1979-1982

- Strings 1-20, 1980

- Strings 1-62, 1980

- Exquisite Corpse, 1980-1982

- On the Surface, 1980-1982

- Déreau, 1982

- HV, 1983

- Weather-ed, 1983

- Weather-ed I-XII, 1983

- Where R = Ryoanji, 1983

- Weather-ed II, 1984

- Fire, 1985

- Mesostics: Earth, Air, Fire, Water, 1985

- Ryoku, 1985

- Eninka, 1986

- Deka, 1987

- Variations, 1987

- Where There Is Where There, 1987

- New River Watercolors, 1988

- Dramatic Fire, 1989

- Edible Drawings, 1989

- Global Village 1-36, 1989

- Global Village 37-48, 1989

- The Missing Stone, 1989

- Please Play or The Mother the Father or the Family, 1989

- Stones, 1989

- River Rocks and Smoke, 1990

- Wild Edible Drawings, 1990

- Essay Barcelona, 1991

- Gelbe Musik, 1991

- Medicine Drawings, 1991

- Museumcircle, 1991 (alternate title: Museum Circle)

- Smoke Weather Stone Weather, 1991

- Variations II, 1991

- HV2, 1992

- Rolywholyover: A Circus for Museum, 1992 (unfinished)

- Variations III, 1992

- Without Horizon, 1992

Films and Film scores

- Works of Calder, with Herbert Matter, 1950 (film score for prepared piano, tape)

- The Sun, with Richard Lippold, 1956

- WGBH-TV, with Nam June Paik, 1971

- Stoperas 1 & 2, with Frank Scheffer, 1987

- Wagner’s Ring, with Frank Scheffer, 1987

- Chessfilmnoise, with Frank Scheffer, 1988

- Silent Shadows, with Andrew Schulman, 1989

- One11, with Van Carlson and Henning Lohner, 1992

Sources and reference material

The list and annotations are based on Sara Haefeli, John Cage: A Research and Information Guide, 2018.

Archives and Collections

Cage entrusted his collections to four primary institutions: his correspondence and materials related to music are at Northwestern University, materials related to his writing and publications are at Wesleyan University, materials related to nature and mushrooms are housed at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and his music manuscripts are held at the New York Public Library. However, there are other collections with materials related to Cage as Cage was a prolific letter writer and was well aware of the historical importance of his work.

- David Tudor Papers, Getty Research Institute. The Getty houses Tudor’s realizations of Cage’s music, electronics, correspondence, articles and reviews, ephemera, personal and financial records, photographs, audio recordings, and video recordings. The transcript of the unpublished five-hour interview Thomas Hines conducted shortly before Cage’s death is housed here.

- John Cage Collection, Northwestern University Music Library, Evanston, Illinois. Houses Cage’s correspondence, the scores that were collected and published in Notations, scrapbooks, and ephemera.

- John Cage Music Manuscript Collection, Performing Arts Research Collections, Music Division, New York Public Library. Houses the vast majority of Cage’s music manuscripts and sketches. The library does not offer a finding aid for this collection. The manuscripts are organized under the call number JPB 95–3. One can browse the catalog by call number or search the catalog by the name of the work.

- John Cage Mycology Collection, University of California, Santa Cruz, Special Collections and Archives, Collection MS74. Houses materials related to Cage’s interest in mushrooms, including his books, correspondence, journals, newsletters, pamphlets, and ephemera.

- John Cage Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut. Houses materials related to the publication of Cage’s books. This includes manuscripts and corrected typescripts, interviews, letters, and ephemera.

- John Cage Trust, Bard College, Red Hook, New York. Houses music, text, and visual art manuscripts; audio, video, and print libraries; and a collection of visual art works.

- Margarete Roeder Gallery, New York, New York. The gallery represents the estates of John Cage and Merce Cunningham and assists with the organization of gallery and museum exhibits of Cage’s visual art and films.

- Merce Cunningham Dance Foundation Archives, New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts. Includes administrative records, company management records, technical files (including information on staging, instrumentation, lighting, etc.), development records, repertory production files, photographs, programs, and press and publicity documents.

Databases and Web sources

- Internet Archive. Nonprofit online library of books, videos, music, and websites. Includes archival video and audio of interviews or performances with Cage. Some digitized book resources as well. New resources are continually added.

- "John Cage", National Gallery of Art. The NGA owns approximately 100 Cage items, including the plexigrams Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel, drawings, lithographs, etchings, burned and smoked paper, watercolors, scores, and sketches. Images and descriptions included for each item.

- John Cage Trust. The John Cage Trust curates a collection of resources online, including the database of works, Cage’s personal library, and a calendar of events. Includes a page called “folksonomy” where individuals can contribute memories and anecdotes about Cage. Links to apps: 4‘33”, Prepared Piano, and Reunion. Links to resources on Empty Words, including audio and video of Cage in Milan. Laura Kuhn’s blog is a source of news on new publications, performances, and research.

- John Cage and the Concert for Piano and Orchestra, a website and apps exploring John Cage’s Concert For Piano And Orchestra, by Universities of Huddersfield and Leeds.

- "John Cage Unbound: A Living Archive", New York Public Library. Created in celebration of Cage’s 100th birthday, this archive of video performances of Cage’s music is designed to demonstrate the continued liveliness and significance of the composer’s work. Also includes links to selected images of Cage manuscripts from the NYPL archives.

- "RadiOM", Other Minds Radio. Links to archived audio of radio programs, including interviews and performances.

- Josh Ronsen, "John Cage Online". Collection of links to Cage resources. Includes links to lists of works, discographies, interviews with Cage, writings by Cage, articles and essays about Cage, paintings and visual art by Cage, audio files, videos, and photos of Cage.

- Silence ListServ. Email listserv for discussions of Cage’s work, performances, and related topics. Many of the subscribers are experts who have worked with Cage and/or have published on Cage. Includes searchable archives. Previously hosted by New Albion Records.

- Michael Tilson Thomas. "Making the Right Choices: A John Cage Celebration", New World Symphony. In celebration of Cage’s 100th birthday, Tilson Thomas and the New World Symphony presented a festival in February 2013. Videos of twelve performances, almost two dozen “behind the scenes” videos, and almost a dozen videos about organizing and funding the festival are available here.

- "John Cage (1912-1992)", UbuWeb. Organized into sections: sound, film, historical, and conceptual writing. Includes full-length albums, tracks, and archival audio; rare video footage; images of selected correspondence and mesostics; a discussion of Cheap Imitation; and essays by Perloff.

Writings by Cage (selection)

Cage was a prolific writer, often blurring the boundaries between the genres of lecture, poetry, biography, autobiography, music, and criticism. Many of his writings were printed in periodicals and then reprinted in collections.

- "The Future of Music: Credo" [1937?], liner notes for record KO8Y 1499-1504, New York: George Avakian, 1959, booklet pp [2]-[4]; repr. in Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings, 1961, pp 3-6; repr., Music Journal 20, New York, Jan 1962, pp 44-46, 80-83; repr. in John Cage, ed. Richard Kostelanetz, New York: Praeger, 1970, pp 54-57; repr. in Sound by Artists, eds. Dan Lander and Micah Lexier, Banff, Alberta: Banff Center, 1990, pp 15-19; repr. in But What about the Noise: John Cage 1912-1992, eds. Ivo van Emmerik, et al., Groningen: Stichting Prime, 1992, pp 35-37; repr. in Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, eds. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner, New York: Continuum, 2004, pp 25-28. Structured as a Credo with a gloss, this early lecture is a clear statement on Cage’s interest in noise, technology, and percussion music and his desire to establish a center for experimental music. Miller (2002) claims that it was likely written in 1940, not 1937 as indicated in the introduction. Given as a talk at a meeting of a Seattle Arts Society organized by Bonnie Bird in 1937?. First printed in the brochure accompanying George Avakian's recording of Cage's twenty-five-year retrospective concert at Town Hall, New York, in 1958.

- "Musikens framtid: Credo", in Cage, Om ingenting: texter, eds. & trans. Torsten Ekbom and Leif Nylén, Stockholm: Albert Bonniers, 1966, pp 9-12. (Swedish)

- "Il futuro della musica: Credo", trans. Renato Pedio, in Cage, Silenzio: Antologia da Silence e A Year from Monday, Milan: Feltrinelli, 1971, pp 24-26; repr., 1980. (Italian)

- "El futuro de la música: Credo", trans. Pilar Gómez Bedate, Revista de Letras 3(11): "John Cage. Varios escritos", Mayagüez, Sep 1971, pp 398-402. (Spanish)

- "Die Zukunft der Musik - Credo", in Richard Kostelanetz, John Cage, trans. Iris Schnebel and Hans Rudolf Zeller, Cologne: M. DuMont Schauberg, 1973, pp 83-85; repr. in Sehen um zu hören: Objekte & Konzerte zur visuellen Musik der 60ger Jahre, ed. Inge Baecker, Düsseldorf: Städtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1975, pp 13-14; repr. in Für Augen und Ohren, eds. René Block, et al., Berlin: Akademie der Künste, 1980, pp 174-175; repr. in Musik – zur Sprache gebracht: Musikästhetische Texte aus drei Jahrhunderten, eds. Carl Dahlhaus and Michael Zimmermann, Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch, 1984, pp 395-398. (German)

- "El futuro de la música: Credo", in Richard Kostelanetz, Entrevista a John Cage, trans. José Manuel Álvarez and Ángela Pérez, Barcelona: Anagrama, 1973, 65-70. (Spanish)

- "Budućnost muzike: Credo", trans. Filip Filipović, in John Cage: radovi/tekstovi 1939-1979: izbor, eds. Miša Savić and Filip Filipović, Belgrade: Radionica SIC, 1981, pp 19-21. (Serbo-Croatian)

- "A zene jövője: Credo", trans. Kata Weber, in Cage, A csend: Válogatott írások, ed. András Wilheim, Pécs: Jelenkor, 1994, pp 7-9. (Hungarian)

- "Budushcheye muzyki: Credo", trans. Elena Dubinets and Svetlana Zavrazhnova, Muzykal’naya Akademiya 2, 1997, p 210-211. (Russian)

- "El futuro de la música: Credo", trans. Marina Pedraza, in Cage, Silencio: conferencias y escritos, Madrid: Árdora, 2002, pp 3-6. (Spanish)

- "Budoucnost hudby: Credo", in Cage, Silence: přednášky a texty, Prague: Tranzit, 2010, pp 3-6. (Czech)

- "Budushcheye muzyki: Credo" [Будущее музыки: кредо], in Dzhon Keydzh (DzДжон Кейдж), Tishina: lektsii i stati [Тишина: лекции и статьи], trans. Marina Pereverzeva, Vologda: Poligraf-Kniga, 2012, pp 13-17. (Russian)

- "Müziğin Geleceği: Credo", trans. Semih Fırıncıoğlu, in Cage, Seçme Yazılar, ed. Semih Fırıncıoğlu, Istanbul: Pan Yayıncılık, 2012. (Turkish)

- "A Composer’s Confessions" / "Bekenntnisse eines Komponisten" [1948], trans. Gisela Gronemeyer, MusikTexte 40-41, Aug 1991, pp 55-68. Cage gave this lecture on 28 February 1948 at Vassar College. He describes his early life, music education, and compositions. He describes working with dancers, the prepared piano and early percussion works, and the rhythmic structures. He also describes his first encounters with Eastern philosophies. Most notably, perhaps, is his desire to make electro-acoustic music with technology that did not yet exist and the desire to write a silent piece called Silent Prayer. (English)/(German)

- "A Composer's Confessions", Musicworks 52, Spring 1992, pp 6-15; repr. in John Cage, Writer: Previously Uncollected Pieces, ed. Richard Kostelanetz, New York: Limelight, 1993, pp 27-44.

- "Egy zeneszerző vallomása", trans. Kata Weber, in Cage, A csend: Válogatott írások, ed. András Wilheim, Pécs: Jelenkor, 1994, pp 10-24. (Hungarian)

- "Confessioni di un compositore", trans. Franco Nasi, in John Cage, eds. Gabriele Bonomo and Giuseppe Furghieri, Milan: Marcos y Marcos, 1998, pp 43-58. (Italian)

- "Confessions d'un compositeur" / "A Composer’s Confessions", trans. Geneviève Bégou, Tacet: Experimental Music Review 1, Dec 2011. (French)/(English)

- Confessions d'un compositeur, trans. Élise Patton, Paris: Allia, 2013, 96 pp. Publisher. (French)/(English)

- "Priznaniya kompozitora" [Признания композитора], trans. Marina Pereverzeva, Nauchnyj Vestnik Moskovskoj Konservatorii 1, Moscow, 2014. (Russian)

- "Forerunners of Modern Music", The Tiger’s Eye 1:7, New York, Mar 1949, pp 52-56; repr. in Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings, 1961, pp 62-66; repr. in Twentieth-Century Music, ed. Ellen Rosand, New York: Garland Publishing, 1985, pp 136-140; repr. in Ann Eden Gibson, Issues in Abstract Expressionism: The Artists-Run Periodicals, Ann Arbor, MI, 1990. Cage describes his compositional philosophy and cites Meister Eckhart’s purpose of music (edification, peace, love).

- "Raison d’être de la musique moderne", trans. Frederick Goldbeck, Contrepoints 6, Paris, 1949, pp 55-61; repr., La revue musicale 306-307, 1977, pp 41-46. (French)

- "Precursori della musica moderna", trans. Renato Pedio, in Cage, Silenzio: Antologia da Silence e A Year from Monday, Milan: Feltrinelli, 1971, pp 37-41. (Italian)

- "Precursores de la música [moderna]", trans. Pilar Gómez Bedate, Revista de Letras 3(11): "John Cage. Varios escritos", Mayagüez, Sep 1971, pp 420-427. (Spanish)

- "A modern zene előhírnökei", trans. Kata Weber, in Cage, A csend: Válogatott írások, ed. András Wilheim, Pécs: Jelenkor, 1994, pp 31-35. (Hungarian)

- "Precursores de la música moderna", trans. Marina Pedraza, in Cage, Silencio: conferencias y escritos, Madrid: Árdora, 2002, pp 62-66. (Spanish)

- "Predshestvenniki sovremennoy muzyki" [Предшественники современной музыки], trans. Marina Viktorovna Pereverzeva, in Kompozitory o sovremennoj kompozicii: Khrestomatiya [Композиторы о современной композиции: хрестоматия], eds. Tatyana Surenovna Kyuregyan and Valeriya Stefanovna Tsenova, Moscow: Gosudarstvennaya Konservatoriya imeni P.I. Chajkovskogo, 2009, pp 33-38; repr. in Dzhon Keydzh (DzДжон Кейдж), Tishina: lektsii i stati [Тишина: лекции и статьи], trans. Marina Pereverzeva, Vologda: Poligraf-Kniga, 2012, pp 84-91. (Russian)

- "Předchůdci moderní hudby", in Cage, Silence: přednášky a texty, Prague: Tranzit, 2010, pp 62-66. (Czech)

- "Composition", trans/formation 1:3, New York, 1952; repr. in Silence: Lectures and Writings, 1961, pp 57-61. Cage describes his recent work, Imaginary Landscape No. 4, including its construction and use of chance operations.

- "Kompozice", in Cage, Silence: přednášky a texty, Prague: Tranzit, 2010, pp 57-61. (Czech)

- "Kompozitsiya" [Композиция], in Dzhon Keydzh (DzДжон Кейдж), Tishina: lektsii i stati [Тишина: лекции и статьи], trans. Marina Pereverzeva, Vologda: Poligraf-Kniga, 2012, pp 78-83. (Russian)

- "Experimental Music" [1957], liner notes for record KO8Y 1499-1504, New York: George Avakian, 1959, booklet pp [6]-[8]; repr. (slightly abridged and without the footnote) in Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings, 1961, pp 7-12; repr. in The American Experience: A Radical Reader, eds. Harold Jaffe and John Tytell, New York: Harper and Row, 1970, pp 327-331; repr. in But What about the Noise: John Cage 1912-1992, eds. Ivo van Emmerik, et al., Groningen: Stichting Prime, 1992, pp 42-47; repr. in Classic Essays on Twentieth-Century Music, eds. Richard Kostelanetz and Joseph Darby, New York: G. Schirmer, 1996, pp 202-206; repr. in Source Readings in Music History. ed. Oliver Strunk, rev.ed. Leo Treitler. New York: Norton, 1998, pp 1300-1305; repr. in The Twentieth Century, ed. Robert P. Morgan, New York: Norton, 1998, pp 30-35. In this February 1957 address to the convention of the Music Teachers National Association in Chicago, Cage defines experimental music as the music that interests him. This music embraces sounds and silences and is open to the environment. Cage writes about his interest in technology (especially tape), chance and indeterminacy, and theater. First printed in the brochure accompanying George Avakian's recording of Cage's twenty-five-year retrospective concert at Town Hall, New York, in 1958.

- "Experimentell musik", in Cage, Om ingenting: texter, eds. & trans. Torsten Ekbom and Leif Nylén, Stockholm: Albert Bonniers, 1966, pp 14-19. (Swedish)

- "Musica sperimentale", trans. Renato Pedio, in Cage, Silenzio: Antologia da Silence e A Year from Monday, Milan: Feltrinelli, 1971, pp 27-31; repr., 1980. (Italian)

- "La música experimental", trans. Pilar Gómez Bedate, Revista de Letras 3(11): "John Cage. Varios escritos", Mayagüez, Sep 1971, pp 404-411. (Spanish)

- "Eksperimentalna muzika", trans. Filip Filipović, in John Cage: radovi/tekstovi 1939-1979: izbor, eds. Miša Savić and Filip Filipović, Belgrade: Radionica SIC, 1981, pp 22-26. (Serbo-Croatian)

- "Az experimentális zene", trans. Kata Weber, in Cage, A csend: Válogatott írások, ed. András Wilheim, Pécs: Jelenkor, 1994, pp 36-40. (Hungarian)

- "Experimentálna hudba", trans. Jozef Cseres, in Avalanches 1990-95. Zborník spoločnosti pre nekonvenčnú hudbu, ed. Michal Murin, Bratislava: SNEH, 1995, pp 138-141. (Slovak)

- "Ėksperimental’naja muzyka: Fragment", trans. Elena Dubinets and Svetlana Zavrazhnova, Muzykal’naya Akademiya 2, 1997, p 211. Excerpt. (Russian)

- "Música experimental", trans. Marina Pedraza, in Cage, Silencio: conferencias y escritos, Madrid: Árdora, 2002, pp 7-12. (Spanish)

- "Experimentální hudba", in Cage, Silence: přednášky a texty, Prague: Tranzit, 2010, pp 7-12. (Czech)

- "Eksperimental'naya muzyka" [Экспериментальная музыка], in Dzhon Keydzh (DzДжон Кейдж), Tishina: lektsii i stati [Тишина: лекции и статьи], trans. Marina Pereverzeva, Vologda: Poligraf-Kniga, 2012, pp 18-23. (Russian)

- "Deneysel Müzik", trans. Semih Fırıncıoğlu, in Cage, Seçme Yazılar, ed. Semih Fırıncıoğlu, Istanbul: Pan Yayıncılık, 2012. (Turkish)

- with Kathleen Hoover, Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music, New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959, 341 pp; repr., Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1970. In 1949 Thomson asked Cage to write his biography and Cage agreed, but the process was difficult and contentious. The book received mixed reviews. Review: Thomson (NYRB).

- Virgil Thomson: Sa vie, sa musique, trans. Lily Jumal, Paris: Buchet-Chastel, 1962. (French)

- "On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Work", Metro 2, Milan, May 1961, pp 36-51; repr. in Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961, pp 98-108.

- "“Om Robert Rauschenberg, konstnär, och hans arbete", Konstrevy 37:5-6, Stockholm, 1961, p 166; repr. in Cage, Om ingenting: Texter, eds. & trans. Torsten Ekbom and Leif Nylén, Stockholm: Albert Bonniers, 1966, pp 64-76. (Swedish)

- "Su Robert Rauschenberg, artista, e la sua opera", trans. Renato Pedio, in Cage, Silenzio: Antologia da Silence e A Year from Monday, Milan: Feltrinelli, 1971, pp 120-129. (Italian)

- "O Robercie Rauschenbergu, artyście i jego dziele", trans. Jerzy Jarniewicz, Literatura na Świecie 1-2, 1996, pp 123-136. (Polish)

- "Robert Rauschenberg, umělec a jeho dílo", in Cage, Silence: přednášky a texty, Prague: Tranzit, 2010, pp 98-108. (Czech)

- "O khudozhnike Roberte Raushenberge i yego rabotakh" [О художнике Роберте Раушенберге и его работах], in Dzhon Keydzh (DzДжон Кейдж), Tishina: lektsii i stati [Тишина: лекции и статьи], trans. Maria Fadeeva, Vologda: Poligraf-Kniga, 2012, pp 128-137. (Russian)

- Silence: Lectures and Writings, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961, 276 pp, PDF, IA; repr., Toronto: Burns & MacEachern, 1961; repr., Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966; repr., London: Calder & Boyars, 1968; repr., Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1973, 276 pp, PDF; 50th anniv.ed., forew. Kyle Gann, Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 2011, PDF. Cage’s first collection of writings to be published with works up to 1961, including: “The Future of Music: Credo”; “Experimental Music”; “Experimental Music: Doctrine”; “Composition as Process”; “Composition”; “Forerunners of Modern Music”; “History of Experimental Music in the United States”; “Erik Satie”; “Edgard Varèse”; “Four Statements on the Dance”; “On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Work”; “Lecture on Nothing”; “Lecture on Something”; “45' for a Speaker”; “Where Are We Going? and What Are We Doing?”; “Indeterminacy”; and “Music Lovers’ Field Companion.”

- Silence. Vortrag über nichts, Vortrag über etwas, 45' für einen Sprecher, ed. Helmut Heißenbüttel, trans. Ernst Jandl, Neuwied: Luchterhand, 1969, 92 pp. Partial trans. (German)

- Silence: discours et écrits, trans. Monique Fong-Wust, Paris: Denoël, 1970; repr., Paris: Denoël, 2004. Partial trans. (French)

- Silenzio: Antologia da Silence e A Year from Monday, trans. Renato Pedio, Milan: Feltrinelli, 1971; repr., 1980. Partial trans. (Italian)

- A csend: válogatott írások, ed. Wilheim András, trans. Kata Weber, Pécs: Jelenkor, 1994, 207 pp. Partial trans., includes seven essays from Silence. (Hungarian)

- Sairensu [サイレンス], trans. Toshie Kakinuma (柿沼敏), Tokyo: Suiseisha (水声社), 1996, 456 pp. (Japanese)

- Silencio: conferencias y escritos, trans. Marina Pedraza, afterw. Juan Hidalgo, Madrid: Árdora, 2002, xii+288 pp. Part. Review: Iges (RdL). (Spanish)

- Silence: conférences et écrits, trans. Vincent Barras, Geneva: Héros-Limite, 2003; rev.ed., Geneva: Héros-Limite, and Contrechamps, 2012. (French)

- Silenzio, trans. G. Carlotti, Milan: Shake, 2008, 325 pp. TOC. (Italian)

- Silence: přednášky a texty, trans. Jaroslav Šťastný, Radoslav Tejkal, and Matěj Kratochvíl, afterw. Jaroslav Šťastný, Prague: Tranzit, 2010, xii+279 pp. TOC. (Czech)

- Tishina: lektsii i stati [Тишина: лекции и статьи], trans. Grigorij Durnovo et al., Vologda: Poligraf-Kniga, 2012, 381 pp. (Russian)

- Chen mo: Wu shi zhou nian ji nian ban [沉默: 五十周年纪念版], trans. Jingying Li, Gui lin: Lijiang (漓江), 2013, 386 pp. Trans. of 50th anniversary ed. (Chinese)

- Sailleonseu: Jon Keijiui gangyeongwa geul [사일런스: 존 케이지의 강연과 글], trans. Na Hyeon Yeong (나현영), Seoul: Openhouse (오픈하우스), 2014, lv+335 pp. (Korean)