Hans Richter

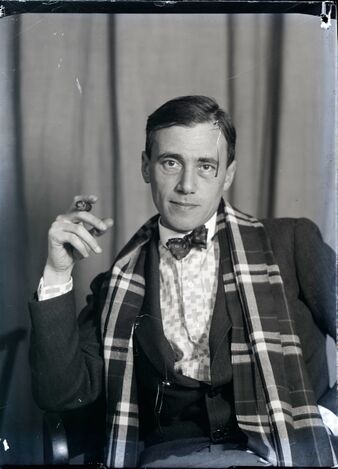

Hans Richter by Man Ray, c1928 | |

| Born |

April 6, 1888 Berlin, German Empire (today Germany) |

|---|---|

| Died |

February 1, 1976 (aged 87) Locarno, Switzerland |

| Web | UbuWeb Film, Dada Companion, Wikipedia |

Hans Richter (1888–1976) was a German artist and filmmaker.

Life and work[edit]

Johannes Siegfried Richter was born into a well-to-do Jewish family in Berlin. Although he wanted to be a painter, his father decided he should pursue architecture and thus Richter spent a year as a carpenter's apprentice. Between 1908 and 1911 Richter studied art at the Academy of Art in Berlin, the Academy of Art in Weimar, and for a brief period at the Académie Julian in Paris.

By 1913 Richter had joined the mainstream of the expressionist circles of the avant-garde, meeting artists associated with Herwarth Walden's Sturm Gallery in Berlin, and the radical expressionists who formed the Brücke in Dresden and the Blaue Reiter in Munich. In 1914 he became part of Die Aktion, an association of expressionist artists and writers gathered around Franz Pfemfert's journal of the same name, who shared socialist and antiwar sympathies. In his graphic work for Die Aktion, which consisted of woodcuts, linocuts, and drawings, Richter began to make a decisive break with representational art. Though these works were often portraits of political or literary figures associated with the journal, their emphasis was on the stark impression made by juxtapositions of black and white shapes. The connection established in the context of Die Aktion between abstraction and engaged politics would be present throughout Richter's life and work.

When Richter was inducted into the army in September 1914, he and his friends, Ferdinand Hardekopf and Albert Ehrenstein, made a pact to meet again in two years at the Café de la terrasse in Zurich. A few months later, Richter was severely wounded while serving in a light artillery unit in Vilnius, Lithuania. Partially paralyzed, he was sent to recuperate at the Hoppegarten military hospital in Berlin, and in March Richter was officially removed from active duty. After his marriage in late August, Richter and his wife traveled to Switzerland to consult with physicians about his back injuries. There, on September 15, he stopped by the Café de la terrasse, where his two friends were waiting. They introduced him to members of the Dada group--Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, and Marcel's brother Georges, who were sitting at a nearby table.

From 1917 to 1919 Richter was closely involved with Dada events, exhibitions, and publications, showing his paintings with the dadaists for the first time in January at the Galerie Corray. Throughout 1917 he also produced a series of paintings at a pace of three or four a day that he called "visionary portraits." Depicting Dada friends but so abstract as to elude likeness, Richter deliberately painted these portraits at twilight in a trancelike state, in order to escape from the visible world. According to him, these pictures then "took shape before the inner rather than the outer eye," transcending the particularity of the visible in order to attain a universal image. A series of woodcuts called "Dada heads," also made during this period, continued Richter's graphic exploration of abstract portraiture.

In the early spring of 1918 Tristan Tzara introduced Richter to Viking Eggeling, a Swedish painter who had developed a systematic theory of abstract art. Richter, who had been experimenting in his Dada heads with opposing black and white, positive and negative, found in Eggeling a friend and fellow theorist of abstraction. In 1920 they coauthored "Universelle Sprache" [Universal Language], a text defining abstract art as a language based on the polar relationships of elementary forms derived from the laws of human perception. For Richter, the central tenet of this text was that such an abstract language would be "beyond all national language frontiers." He imagined in abstraction a new kind of communication that would be free from the kinds of nationalistic alliances that led to World War I.

Richter and Eggeling also produced an entirely new kind of artwork--the abstract film. Developed out of their theorizations of a universal language of forms, Rhythmus 21 and Rhythmus 23 introduced the element of time into the abstract work of art. Now classics of the cinema, the films show geometric shapes moving and interacting in space and set to a musical score. Richter's 1927 film, Vormittagsspuk [Ghosts before Breakfast], which he developed from Dada ideas, shows everyday objects in rebellion against their owners: derby hats, potent symbols of bourgeois propriety and stability, take on lives of their own, parodying their inept masters.

In 1923 Richter began publishing G, a magazine that drew together the work of artists, architects, and writers associated with Dada, De Stijl, and international constructivism. His films were censored as early as 1927 when the object rebellion of Ghosts before Breakfast was understood as subversive of the social order. As a Jew, a modern artist, and a member of the political opposition, Richter was forced to leave Germany. He eventually emigrated to the United States. (Source)

In the United States, he produced the surrealistic fantasy Dreams that Money Can Buy (1946). Among his other well-known experimental films were 8 × 8 (1947) involving squares on a chess board, and Dadascope (1961). His book Dada – Kunst und Antikunst, published in 1964, became a classic which was followed two years later by an exhibition that toured internationally, Dada 1916–1966: Documents of the International Dada Movement. Richter served as head of the Institute of Film Technique at the City College of New York (1943–56) and then specialized in teaching documentary filmmaking. In 1962 he retired and returned to Switzerland. (Source)

Works[edit]

Films[edit]

- Rhythmus 21, 3 min, c1923-25. [1]

- Rhythmus 23, 3 min, c1923-25.

- Vormittagsspuk, 9 min, 1928.

- Dreams That Money Can Buy, 80 min, 1947.

Writings[edit]

- Dada – Kunst und Antikunst, Cologne: DuMont Schauberg, 1964. (German)

- Dada Art and Anti-Art, trans. David Britt, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965; repr., London: Thames & Hudson, 1997, 246 pp. (English)

- Begegnungen von Dada bis Heute, 1973. (German)

- Encounters from Dada till Today, trans. Christopher Middleton, Los Angeles: LACMA, and Munich: Prestel, 2013, 140 pp. (English)

Literature[edit]

- Stephen C. Foster (ed.), Hans Richter: Activism, Modernism, and the Avant-Garde, MIT Press, with University of Iowa Museum of Art, 1998. (English)

- Erin McClenathan, "Hans Richter’s Rhythmus Films in G: the Collective Cinematographic", InVisible Culture 24, May 2016. (English)

- Magdalena Nieslony, "Felicitous Failure: Hans Richter’s Malevich", Getty Research Journal 9, 2017, pp 141-160.