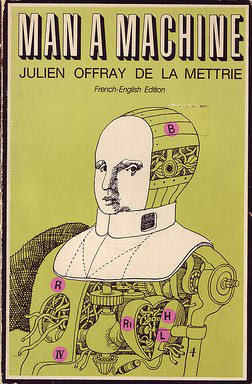

Julien Offray de La Mettrie: Man a Machine (1747-) [FR, EN, TR, DE, PL]

Filed under book | Tags: · body, enlightenment, machine, materialism, philosophy

French physician and Enlightenment thinker Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–51) was the most uncompromising of the materialists of the eighteenth century, and the provocative title of his work ensured it a succès de scandale in his own time.

“In 1747, La Mettrie wrote a small but powerful book arguing that the soul, the human will, and consciousness were all reducible to bodily processes. According to La Mettrie, ‘The human body is a machine which winds its own springs.’

La Mettrie’s L’homme machine (Man a Machine or Machine Man) was likely completed in August of 1747. The book was controversial, arguing against the traditional notion of soul and suggesting that man was no different than any other animal. This small volume espousing this materialist philosophy was just over one hundred pages long, written in forceful but casual prose. Less than half a year after its publication, the book became the center of controversy and led to La Mettrie’s self-exile from Holland.

The book was printed anonymously and copies were circulating in Holland by December. On December 18th, the publisher—Elie Luzac—was called before the Consistory Church of Leyden and ordered to deliver all copies of the book for burning and to promptly reveal the author. The publisher indeed delivered some copies for burning, but claimed he did not know who had written the piece. The following year, the publisher issued two more printings of the book and then promptly left Holland.

In the meantime, rumors began to circulate that La Mettrie was the author of the book. La Mettrie was not naïve about the potential outcomes of this: he had previously fled his native France after the public burning of his 1745 book The Natural History of the Soul. He therefore fled Holland to Berlin on February 7, 1748, where he came under the protection of Frederick the Great who provided him with sanctuary and a small pension and made him the official court physician. La Mettrie died of food poisoning in Potsdam in 1751.” (from Cathy Faye, “Banned and Burned Books: La Mettrie’s L’homme machine“)

commentary (J.E. Poritzky, 1900, German)

commentary (Paul Carus, 1913, English)

commentary (Ernst Bergmann, 1913, German)

commentary (Ann Thomson, 1996, English)

commentary (Peter Gendolla, 2000, English)

wikipedia (English)

L’homme machine (French, 1774, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, 1796, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, 1800, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, With an Introduction and Notes by J. Assezat, 1865, Archive.org)

L’Homme Machine / Man a Machine (French-English, Trans. and With Notes by Gertrude C. Bussey, revised by M.W. Calkins, 1912, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, With an Introduction and Notes by Maurice Solovine, 1921, Archive.org)

İnsan Bir Makine (Turkish, trans. Ehra Bayramoğlu, 1980)

Machine Man (English, trans. Ann Thomson, 1996)

Der Mensch eine Maschine (German, undated)

Człowiek-maszyna (Polish, undated, DJVU)

Peter Linebaugh: Ned Ludd and Queen Mab: Machine-Breaking, Romanticism, and the Several Commons Of 1811-12 (2012)

Filed under pamphlet | Tags: · 1800s, luddism, machine, romanticism

“Peter Linebaugh, in an extraordinary historical and literary tour de force, enlists the anonymous and scorned 19th century loom-breakers of the English midlands into the front ranks of an international, polyglot, many-colored crew of commoners resisting dispossession in the dawn of capitalist modernity.”

Publisher PM Press, Oakland, CA, 2012

Report Pamphlet Series, No. 001

ISBN 9781604867046

48 pages

review (Alan Brooke)

author’s lecture on luddism (audio)

Richard Sennett: The Craftsman (2008)

Filed under book | Tags: · craft, hand, history, labour, machine, technology, work

“Craftsmanship, says Richard Sennett, names the basic human impulse to do a job well for its own sake, and good craftsmanship involves developing skills and focusing on the work rather than ourselves. The computer programmer, the doctor, the artist, and even the parent and citizen all engage in a craftsman’s work. In this thought-provoking book, Sennett explores the work of craftsmen past and present, identifies deep connections between material consciousness and ethical values, and challenges received ideas about what constitutes good work in today’s world.

The Craftsman engages the many dimensions of skill—from the technical demands to the obsessive energy required to do good work. Craftsmanship leads Sennett across time and space, from ancient Roman brickmakers to Renaissance goldsmiths to the printing presses of Enlightenment Paris and the factories of industrial London; in the modern world he explores what experiences of good work are shared by computer programmers, nurses and doctors, musicians, glassblowers, and cooks. Unique in the scope of his thinking, Sennett expands previous notions of crafts and craftsmen and apprises us of the surprising extent to which we can learn about ourselves through the labor of making physical things.”

Publisher Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2008

ISBN 0300149557, 9780300149555

326 pages

review (Lewis Hyde, The New York Times: Sunday Book Review)

review (Fiona MacCarthy, The Guardian)