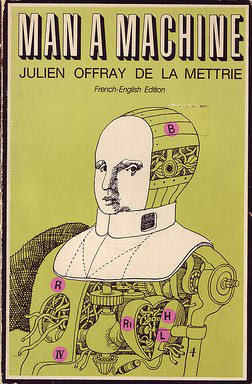

Julien Offray de La Mettrie: Man a Machine (1747-) [FR, EN, TR, DE, PL]

Filed under book | Tags: · body, enlightenment, machine, materialism, philosophy

French physician and Enlightenment thinker Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–51) was the most uncompromising of the materialists of the eighteenth century, and the provocative title of his work ensured it a succès de scandale in his own time.

“In 1747, La Mettrie wrote a small but powerful book arguing that the soul, the human will, and consciousness were all reducible to bodily processes. According to La Mettrie, ‘The human body is a machine which winds its own springs.’

La Mettrie’s L’homme machine (Man a Machine or Machine Man) was likely completed in August of 1747. The book was controversial, arguing against the traditional notion of soul and suggesting that man was no different than any other animal. This small volume espousing this materialist philosophy was just over one hundred pages long, written in forceful but casual prose. Less than half a year after its publication, the book became the center of controversy and led to La Mettrie’s self-exile from Holland.

The book was printed anonymously and copies were circulating in Holland by December. On December 18th, the publisher—Elie Luzac—was called before the Consistory Church of Leyden and ordered to deliver all copies of the book for burning and to promptly reveal the author. The publisher indeed delivered some copies for burning, but claimed he did not know who had written the piece. The following year, the publisher issued two more printings of the book and then promptly left Holland.

In the meantime, rumors began to circulate that La Mettrie was the author of the book. La Mettrie was not naïve about the potential outcomes of this: he had previously fled his native France after the public burning of his 1745 book The Natural History of the Soul. He therefore fled Holland to Berlin on February 7, 1748, where he came under the protection of Frederick the Great who provided him with sanctuary and a small pension and made him the official court physician. La Mettrie died of food poisoning in Potsdam in 1751.” (from Cathy Faye, “Banned and Burned Books: La Mettrie’s L’homme machine“)

commentary (J.E. Poritzky, 1900, German)

commentary (Paul Carus, 1913, English)

commentary (Ernst Bergmann, 1913, German)

commentary (Ann Thomson, 1996, English)

commentary (Peter Gendolla, 2000, English)

wikipedia (English)

L’homme machine (French, 1774, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, 1796, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, 1800, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, With an Introduction and Notes by J. Assezat, 1865, Archive.org)

L’Homme Machine / Man a Machine (French-English, Trans. and With Notes by Gertrude C. Bussey, revised by M.W. Calkins, 1912, Archive.org)

L’homme machine (French, With an Introduction and Notes by Maurice Solovine, 1921, Archive.org)

İnsan Bir Makine (Turkish, trans. Ehra Bayramoğlu, 1980)

Machine Man (English, trans. Ann Thomson, 1996)

Der Mensch eine Maschine (German, undated)

Człowiek-maszyna (Polish, undated, DJVU)

Speculations: A Journal of Speculative Realism, Issue IV (2013)

Filed under journal | Tags: · materialism, ontology, philosophy, speculative realism

With this special issue of Speculations, the editors wanted to challenge the contested term “speculative realism,”offering scholars who have some involvement with it a space to voice their opinions of the network of ideas commonly associated with the name. Whilst undoubtedly born under speculative realist auspices, Speculations has never tried to be the gospel of a dogmatic speculative realist church, but rather instead to cultivate the best theoretical lines sprouting from the resurgence, in the last few years, of those speculative and realist concerns attempting to break free from some of the most stringent constraints of critique. Sociologist Randall Collins observed that, unlike other fields of intellectual inquiry, “[p]hilosophy has the peculiarity of periodically shifting its own grounds, but always in the direction of claiming or at least seeking the standpoint of greatest generality and importance.” If this is the case, to deny that a shift of grounds has indeed become manifest in these early decades of the twenty-first century would be, at best, a sign of a severe lack of philosophical sensitivity. On the other hand, whether or not this shift has been towards greater importance (and in respect to what?) is not only a legitimate but a necessary question to ask.

Whatever the intrinsic value in the name, the contributors to this volume have all engaged, more or less directly, with a critical analysis of the vices and virtues of “speculative realism”: from the extent to which its adversarial stance towards previous philosophical stances is justified to whether it succeeds (or fails) to address satisfactorily the concerns that ostensibly motivate it, through to an assessment of the methods of dissemination of its core ideas. The contributions are divided in two sections, titled “Reflections” and “Proposals,” describing, with some inevitable overlap, two kinds of approach to the question of speculative realism: one geared towards its retrospective and its critical appraisal, and the other concerned with the positive proposition of alternative or parallel approaches to it. It is believed that the final result, in its heterogeneity, will be of better service to the philosophical community than a dubiously univocal descriptive recapitulation of “speculative realist tenets.”

Edited by Michael Austin, Paul John Ennis, Fabio Gironi, Thomas Gokey, and Robert Jackson

Publisher Punctum Books, Brooklyn/NY, June 2013

Open Access

ISBN 9780615758282

ISSN 2327-803X

121 pages

PDF (single PDF)

PDF (PDF articles)

Karen Barad: Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (2007)

Filed under book | Tags: · agency, agential realism, apparatus, epistemology, ethics, materialism, ontology, philosophy, physics, posthumanism, quantum mechanics, quantum physics, science

“Meeting the Universe Halfway is an ambitious book with far-reaching implications for numerous fields in the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. In this volume, Karen Barad, theoretical physicist and feminist theorist, elaborates her theory of agential realism. Offering an account of the world as a whole rather than as composed of separate natural and social realms, agential realism is at once a new epistemology, ontology, and ethics. The starting point for Barad’s analysis is the philosophical framework of quantum physicist Niels Bohr. Barad extends and partially revises Bohr’s philosophical views in light of current scholarship in physics, science studies, and the philosophy of science as well as feminist, poststructuralist, and other critical social theories. In the process, she significantly reworks understandings of space, time, matter, causality, agency, subjectivity, and objectivity.

In an agential realist account, the world is made of entanglements of “social” and “natural” agencies, where the distinction between the two emerges out of specific intra-actions. Intra-activity is an inexhaustible dynamism that configures and reconfigures relations of space-time-matter. In explaining intra-activity, Barad reveals questions about how nature and culture interact and change over time to be fundamentally misguided. And she reframes understanding of the nature of scientific and political practices and their “interrelationship.” Thus she pays particular attention to the responsible practice of science, and she emphasizes changes in the understanding of political practices, critically reworking Judith Butler’s influential theory of performativity. Finally, Barad uses agential realism to produce a new interpretation of quantum physics, demonstrating that agential realism is more than a means of reflecting on science; it can be used to actually do science.”

Publisher Duke University Press, 2007

ISBN 082238812X, 9780822388128

xiii+524 pages

Reviews: S.S. Schweber (Isis, 2008), Sherryl Vint (Science Fiction Studies, 2008), Peta Hinton (Australian Feminist Studies, 2008), Lisa M. Dolling (Hypatia, 2009), Vita Peacock (Opticon1826, 2010), Beatriz Revelles Benavente (Graduate Journal of Social Science, 2010), Trevor Pinch (Social Studies of Science, 2011), Haris Durrani (2015).

Commentaries: Levi R. Bryant, Steven Craig Hickman.

PDF, PDF (updated on 2018-11-4)

Comments (3)