Paul Klee: Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925–) [DE, EN, GR, RU]

Filed under book | Tags: · art, art education, bauhaus, colour, design, drawing, painting, theory

“Paul Klee occupies a unique position among the creators of modern art. Although he shed all ties with conventional presentation, he developed a closer and deeper relationship to reality than did most painters of his time. Without any attempt at imitation or idealization, he recorded proportion, motion, and depth in space as the fundamental attributes of the visual world.

Klee collected his observations in his Pedagogical Sketchbook intended as the basis for the course in design theory at the famous Bauhaus art school in Germany. From the simple phenomenon of interweaving lines, his work leads to the comprehension of defined planes-of structure, dimension, equilibrium, and motion. But he employs no abstract formulas. The student remains in the familiar world-a world that acquires new significance through the straight forward approach of Klee’s simple, lucid drawings and his precise captions. Chessboard, bone, muscle, heart, a water wheel, a plant, railroad ties, a tightrope walker-these serve as examples for the forty-three design lessons.

Pedagogical Sketchbook is a vital contribution toward a more human, more universal goal in design education the work of a visionary painter who dedicated himself to the practical task of making people see.” (from the Back cover)

Publisher Albert Langen, Munich, 1925

Volume 2 of Bauhausbücher series

50 pages

English edition

Introduction and Translation by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy

Publisher Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1953

The original layout by L. Moholy-Nagy has been retained

65 pages

Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch (German, 33 MB, via Bibliothèque Kandinsky, added on 2014-8-17, updated on 2022-4-13)

Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch (German, PDF, JPG, in Heidelberg U Library, added on 2019-7-7)

Pedagogical Sketchbook (English, 1953 edition, no OCR)

Pedagogical Sketchbook (English, 1960 edition, 7th printing from 1972)

Παιδαγωγικό Σημειωματάριο (Greek, trans. Β. Λαγοπούλου, 1976)

Pedagogikheskie eskizy (Russian, trans. N. Druzhkovoy, 2005, added on 2014-3-6)

See also other titles in the Bauhaus Books series, as well as Klee’s class notes in manuscript and an edited version of his Notebooks.

Comments (10)Ivan Edward Sutherland: Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System (1963/2003)

Filed under thesis | Tags: · computing, design, drawing, interface, software, technology

This technical report is based on a dissertation submitted January 1963 by the author for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

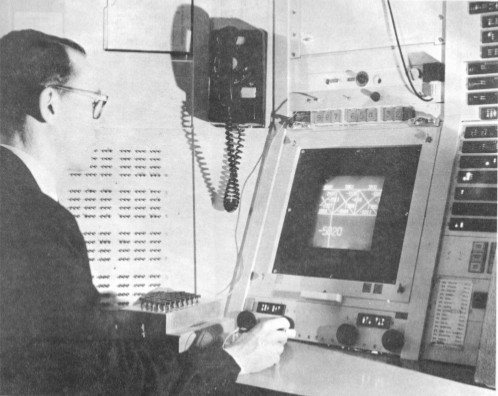

“The Sketchpad system uses drawing as a novel communication medium for a computer. The system contains input, output, and computation programs which enable it to interpret information drawn directly on a computer display. It has been used to draw electrical, mechanical, scientific, mathematical, and animated drawings; it is a general purpose system. Sketchpad has shown the most usefulness as an aid to the understanding of processes, such as the notion of linkages, which can be described with pictures. Sketchpad also makes it easy to draw highly repetitive or highly accurate drawings and to change drawings previously drawn with it. The many drawings in this thesis were all made with Sketchpad.

A Sketchpad user sketches directly on a computer display with a ‘light pen.’ The light pen is used both to position parts of the drawing on the display and to point to them to change them. A set of push buttons controls the changes to be made such as ‘erase,’ or ‘move.’ Except for legends, no written language is used.

Information sketched can include straight line segments and circle arcs. Arbitrary symbols may be defined from any collection of line segments, circle arcs, and previously defined symbols. A user may define and use as many symbols as he wishes. Any change in the definition of a symbol is at once seen wherever that symbol appears.

Sketchpad stores explicit information about the topology of a drawing. If the user moves one vertex of a polygon, both adjacent sides will be moved. If the user moves a symbol, all lines attached to that symbol will automatically move to stay attached to it. The topological connections of the drawing are automatically indicated by the user as he sketches. Since Sketchpad is able to accept topological information from a human being in a picture language perfectly natural to the human, it can be used as an input program for computation programs which require topological data, e.g., circuit simulators.

Sketchpad itself is able to move parts of the drawing around to meet new conditions which the user may apply to them. The user indicates conditions with the light pen and push buttons. For example, to make two lines parallel, he successively points to the lines with the light pen and presses a button. The conditions themselves are displayed on the drawing so that they may be erased or changed with the light pen language. Any combination of conditions can be defined as a composite condition and applied in one step.

It is easy to add entirely new types of conditions to Sketchpad’s vocabulary. Since the conditions can involve anything computable, Sketchpad can be used for a very wide range of problems. For example, Sketchpad has been used to find the distribution of forces in the members of truss bridges drawn with it.

Sketchpad drawings are stored in the computer in a specially designed ‘ring’ structure. The ring structure features rapid processing of topological information with no searching at all. The basic operations used in Sketchpad for manipulating the ring structure are described.” (from the Abstract)

PhD thesis

Originally submitted at the Massachussets Institute of Technology, January 1963

Technical report published by University of Cambridge, September 2003

New preface by Alan Blackwell and Kerry Rodden

ISSN 1476-2986

149 pages

Sketchpad presentation with comments by Alan Kay (video)

PDF (original thesis, 1963)

PDF (2003 edition)

Wolfgang Lefèvre (ed.): Picturing Machines 1400-1700 (2004)

Filed under book | Tags: · architecture, data visualisation, drawing, engineering, geometry, history of science, history of technology, media archeology, science, technology

“Technical drawings by the architects and engineers of the Renaissance made use of a range of new methods of graphic representation. These drawings—among them Leonardo da Vinci’s famous drawings of mechanical devices—have long been studied for their aesthetic qualities and technological ingenuity, but their significance for the architects and engineers themselves is seldom considered. The essays in Picturing Machines 1400-1700 take this alternate perspective and look at how drawing shaped the practice of early modern engineering. They do so through detailed investigations of specific images, looking at over 100 that range from sketches to perspective views to thoroughly constructed projections.

In early modern engineering practice, drawings were not merely visualizations of ideas but acted as models that shaped ideas. Picturing Machines establishes basic categories for the origins, purposes, functions, and contexts of early modern engineering illustrations, then treats a series of topics that not only focus on the way drawings became an indispensable means of engineering but also reflect the main stages in their historical development. The authors examine the social interaction conveyed by early machine images and their function as communication between practitioners; the knowledge either conveyed or presupposed by technical drawings, as seen in those of Giorgio Martini and Leonardo; drawings that required familiarity with geometry or geometric optics, including the development of architectural plans; and technical illustrations that bridged the gap between practical and theoretical mechanics.”

Publisher MIT Press, 2004

ISBN 0262122693, 9780262122696

347 pages

PDF (updated on 2019-12-2)

Comment (0)