Dylaby (1962)

Filed under catalogue | Tags: · art, installation art, kinetic art, pop art

“artists gathered from several countries

with the aim to let the public

participate in their work

to let you see, feel, cooperate with them

they start from daily life

the sensations you get

feeling your way through a labyrinth

the surprise when you open a door

the freshness of the coloured world of plastic

the machine that moves

but without practical purpose

the shooting gallery where you don’t destroy

but help to colour the objects …

six artists in seven rooms

created surroundings full of variety

gay and weird, loud and silent

where you may laugh, get excited

or thoughtful

you are not outside the objects

but constantly within them

as part of the whole”

(catalogue introduction)

A visitor to this exhibition “was to navigate a maze constructed by Daniel Spoerri, Per Olof Ultveldt, Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely, Martial Raysse and Robert Rauschenberg. The labyrinth was made largely from scrap metal and spanned seven rooms of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. After feeling their way through Spoerri’s darkened maze, and weathering a number of wooden obstacles by Ultveldt, the participant ended up in a room where paintings ‘hung’ from the floor and marbles ‘stood’ on the walls.

To finish the trail, one had to splash around Raysse’s beach, fire a gun at Saint-Phalle’s shooting painting, turn right at Rauschenberg’s caged clocks and exit through Tinguely’s balloon-filled room. The terms ‘playground’ and ‘funfair’, frequently used by a rather sceptical press, were apt descriptions of what transpired in the museum galleries. Art as conceived in Dylaby required active engagement on the part of the visitor. The exhibition followed in the wake of Bewogen Beweging [Art in Motion] (1961), another Stedelijk Museum exhibition of interactive kinetic art, initiated by Tinguely the year before. The curatorial program was a response to the 1961 ‘a-dynamic manifesto’ of Dutch artists Ger van Elk and Wim T. Schippers, who berated the artistic pretentiousness of abstract expressionism that dominated museums.

The exhibition was a forebode of the ‘happenings’ that would take Amsterdam by storm from the mid-1960s. As the artwork now became a temporary experience that relied heavily on audience participation, its survival relied on photographic documentation. A legion of photographers orbited such cultural figures as Robert Jasper Grootveld and Theo Kley, choreographer Koert Stuyf and frequented the performance stronghold of Ferdi and Tajiri in Limburg.

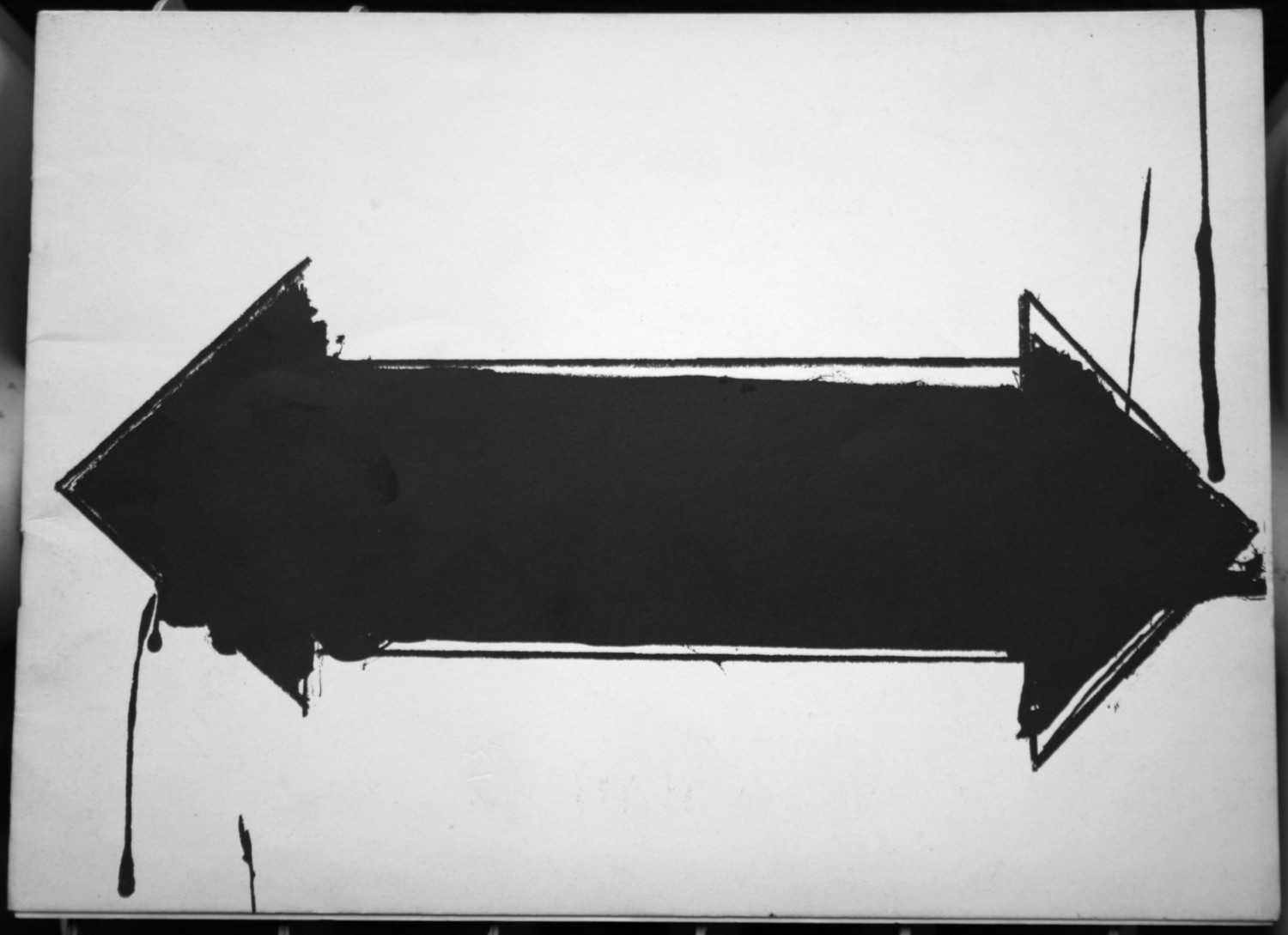

Apart from the introductory text by Willem Sandberg, the Dylaby catalogue almost exclusively consists of visuals. The double arrow on the cover, designed by Rauschenberg, was mounted on a car tire at the entrance of the labyrinth. Van der Elsken’s photographs reiterated the organised chaos of the exhibition. An image of disoriented visitors was rotated 90 degrees on the catalogue page, making them seem as though they were walking sideways on the gallery walls. Van der Elsken followed Tinguely around the Waterlooplein as he was scavenging for bicycle wheels and other metal scrap for his kinetic sculptures. A handwritten foldout in the catalogue features a timetable tracing the artists’ every move in the three weeks preceding the opening. After the show, the props landed in the garbage dump along with the rest of the labyrinth. What is left is an archive of bewildered press reviews; and this catalogue.” (Source)

Cover by Robert Rauschenberg

Introduction by Willem Sandberg

Photographs by Ed van der Elsken

Publisher Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1962

[21] pages

via Bint Bint

Commentary: Paula Burleigh (Stedelijk Studies, 2018).

PDF (35 MB)

Comment (0)Leave a Reply