Christian Bök: Crystallography (1994/2003)

Filed under poetry | Tags: · concrete poetry, language, pataphysics, poetry, science, visual poetry

“Crystallography’ means the study of crystals, but also, taken literally, ‘lucid writing.’ The book exists in the intersection of poetry and science, exploring the relationship between language and crystals – looking at language as a crystal, a space in which the chaos of individual parts align to expose a perfect formation of structure. As Bök himself says, ‘a word is a bit of crystal in formation,’ suggesting there is a space in which words, like crystals, can resonate pure form.”

First edition published 1994

Second edition, revised

Publisher Coach House Books, Toronto, 2003

ISBN 1552451194

157 pages

via ExP

Reviews: Darren Wershler-Henry (2001), Adam Golaski (Open Letters Monthly 2007), Ian Rae (Canadian Literature 2011).

Commentary: Nathan Brown (2004), James Elkins (2014).

PDF (removed on 2016-8-16 upon request of the publisher)

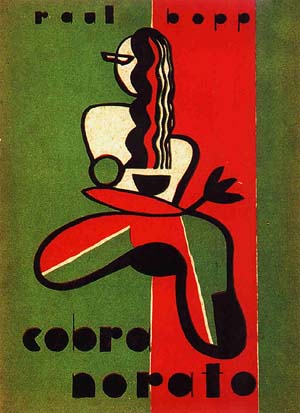

Comment (0)Raul Bopp: Cobra Norato (1931–) [BR-PT, EN]

Filed under poetry | Tags: · anthropophagy, avant-garde, brazil, modernism, poetry

“Raised in the south of Brazil, trained as a lawyer in Recife and Rio, and seasoned as a diplomat in Japan and the United States, Raul Bopp found his true subject in Manaus, where he discovered what he insisted was the authentic Brazil. Bopp brought to the early Modernist movement in Brazil a fascination with the folklore, Indian languages, and culture of the vast hinterland of the Amazon basin. As a contributor to the magazine Revista de Antropofagia (Anthropophagical Review) in the 1920s and 1930s, Bopp defined the concerns of what he called the “Cannibalist school” of poetry. ‘Anthropophagical’ in their appropriative and assimilative relation to European experimental writing, the theories of Bopp and Oswald de Andrade further associated them with the tenets of the cosmopolitan/indigenist “Verde e Amarelo” writers, who took their name (“The Green and Yellow”) from the colors of the Brazilian flag.

His long poem Cobra Norato (The Snake Norato or, as translated by Renato Rezende, Black Snake) was written in 1928 and published in its first version in 1931. In it Bopp embodies his primitivist, mystical sense of the life of Brazil’s interior, whose energy he and the other “Cannibalists” proposed as an alternative to the compromising forces of modern urban life. Skeptical, impressionistic, rhythmically complex, and erotically playful, the poem moves at times like a dream or a fairy tale. Its politics, however, are humanitarian and ecologically alert to the dangers o fexploiting the rain forest and its indigenous cultures. In later editions, Bopp softened the bluntness and difficulty of the poem’s diction, making the tone less austerely visionary and more tender. In his later poems, in his criticism, and in his several volumes of memoirs, Bopp continued his Modernist advocacy of Amazonian and Afro-Brazilian folklore as sources of energy and psychic survival.” (Source)

First published in Rio de Janeiro, 1937.

Cobra Norato / Black Snake (BR-Portuguese/English, trans. Renato Rezende, 1996, excerpts, HTML)

Cobra Norato (English, trans. Chris Daniels, 2008)

Pier Paolo Pasolini: The Divine Mimesis (1975–) [ES, EN]

Filed under poetry | Tags: · 1960s, italy, poetry

“Written between 1963 and 1967, The Divine Mimesis, Pasolini’s imitation of the early cantos of the Inferno, offers a searing critique of Italian society and the intelligentsia of the 1960s. It is also a self-critique by the author of The Ashes of Gramsci (1957) who saw the civic world evoked by that book fading absolutely from view. By the mid-1960s, Pasolini theorized, the Italian language had sacrificed its connotative expressiveness for the sake of a denuded technological language of pure communication. In this context, he projects a ‘rewrite’ of Dante’s Commedia in which two historical embodiments of Pasolini himself occupy the roles of the pilgrim and guide in their underworld journey.

Densely layered with poetic and philological allusions, and illuminated by a parallel text of photographs that juxtapose the world of the Italian literati to the simple reality of rural Italian life, this narrative was curtailed by Pasolini several years before he sent it to his publisher, a few months prior to his murder in 1975. Yet, many of Pasolini’s projects took the provisional form of “Notes toward…” an eventual work, such as Sopralluoghi in Palestina (Location Scouting in Palestine), Appunti per una Oresteiade africana (Notes for an African Oresteia), and Appunti per un film sull’India (Notes for a Film on India). The Divine Mimesis has a kinship to these filmic works as Pasolini himself ruled it ‘complete’ though still in a partial form.

Written at a turning point in his life when he was wrestling with his poetic ‘demons,’ the true center of gravity of Pasolini’s Dantean project is the potential of poetry to teach and probe, ethically and aesthetically, in reality. “I wanted to make something seething and magmatic,” Pasolini declared, “even if in prose.”

In this first English translation of Pasolini’s La divina mimesis, Italianist Thomas E. Peterson offers historical, linguistic, and cultural analyses that aim to expand the discourse about an enigmatic author considered by many to be the greatest Italian poet after Montale.”

First published as La divina mimesis, Einaudi, Turin, 1975.

English edition

Translated by Thomas Erling Peterson

Publisher Double Dance Press, Berkeley, 1980

139 pages

HT Ken, via c0st1c

Review: Thomas Sanfilip (Literary Yard 2016).

Commentary: Manuele Gragnolati (2012).

Publisher (2014 EN edition)

WorldCat (EN)

La divina mímesis (Spanish, trans. Julia Adinolfi, 1976)

The Divine Mimesis (English, trans. Thomas Erling Peterson, 1980, 4 MB)

Introduction to 2014 edition of EN translation