Francis Spufford: Red Plenty: Inside the Fifties’ Soviet Dream (2010)

Filed under book | Tags: · 1950s, 1960s, communism, cybernetics, economy, engineering, history of computing, mathematics, politics, science, soviet union

This book is about the moment in the mid-20th century when people believed that the state-owned Soviet economy might genuinely outdo the market, and produce a world of rich communists and envious capitalists. Specifically, it’s about the last and cleverest version of the idea – central planning via cybernetics – and about how and why, in the 1960s, it failed. To give the economics some human depth, Red Plenty generates a miniature Soviet Union on the page, peopled by scientists and politicians, fixers and managers, dreamers and cynics.

Publisher Faber & Faber, 2010

ISBN 0571269478, 9780571269471

356 pages

EPUB (updated on 2019-11-20)

See also:

Red Plenty Platforms, essay by Nick Dyer-Witheford, Culture Machine 14, 2013

Red Plenty: A Crooked Timber, collection of essays inspired by the book, 2012

David Aubin: A Cultural History of Catastrophes and Chaos: Around the Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques, France 1958-1980 (1998)

Filed under thesis | Tags: · biology, catastrophe theory, chaos theory, history of mathematics, history of science, linguistics, mathematics, oulipo, physics, science, semiotics, structuralism, turbulence

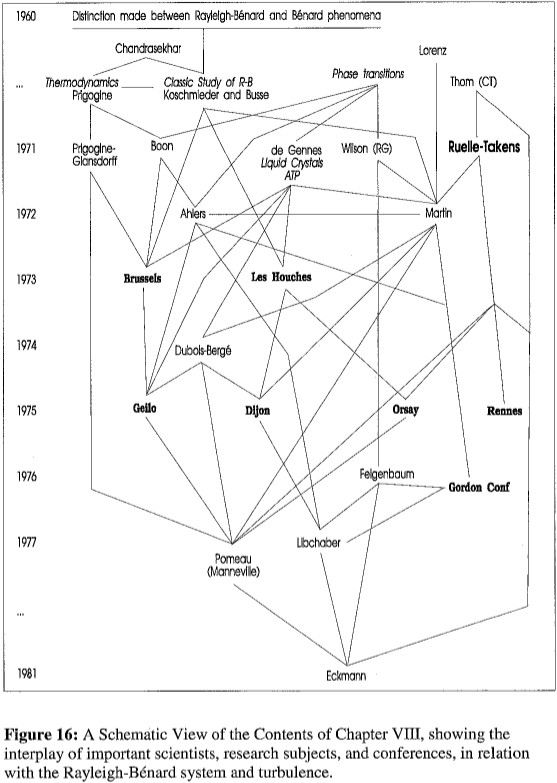

“This is the story of a group of scientists who, in the local context of the Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques (IHÉS), France, contributed to the elaboration of catastrophe theory and deterministic chaos theory. Starting with a study of the role of Bourbaki’s mathematics on the French intellectual scene (and especially with respect to structuralism), this dissertation examines the resources from topology, embryology, and linguistics used by René Thom to construct catastrophe theory.

It describes the foundation of the IHÉS by Léon Motchane in 1958 and the ideology of fundamental research that shaped it. It reviews the history of structural stability for differential equations, focusing on the work of Aleksandr Andronov and Solomon Lefschetz, among others, and the synthesis achieved in the 1960s by Stephen Smale at the University of California, Berkeley. These mathematical developments were used by Thom to develop new modeling practices. The IHÉS, which welcomed topologists such as E. Christopher Zeeman and Ralph Abraham, played a role in developing modeling practices based on recent advances in topology. A physics professor at the IHÉS, David Ruelle, together with Dutch mathematician Floris Takens, adapted the modeling practices of these ‘applied topologists’ and proposed a mechanism for the onset of turbulence, thereby introducing the concept of strange attractors. Looking at the history of fluid mechanics, I argue that Ruelle’s work displaced earlier emphases on fundamental laws, like the Navier-Stokes equations, and focused on the modes of representation rather than representations themselves. A certain Bourbakization of physics and the advent of the computer shaped this evolution.

Finally, focusing on convention, and taking the Rayleigh-Bénard system as a boundary system, various communities’ responses to the Ruelle-Takens model are examined, in particular hydrodynamic stability theorists, phase transition physicists and Pierre-Gilles de Gennes’s group, and chemical physicists orbiting Ilya Prigogine. Prior interest in developing interdisciplinary approaches for the study of turbulence helped the adaptation of a dynamical systems approach for the study of natural phenomena, greatly inspired by the work of Smale, Thom, and Ruelle.” (Abstract)

Ph. D. thesis

Princeton University

782 pages

single PDF (final section “Sources and Bibliography” missing; no OCR)

PDF chapters (from the author’s website)

Martin Davis: The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing (2000–) [EN, IT, CR]

Filed under book | Tags: · biography, computing, history of computing, history of mathematics, logic, machine, mathematics, philosophy of science

“Martin Davis, a fluent interpreter of mathematics and philosophy, locates the source of this knowledge in the work of the remarkable German thinker G. W. Leibniz, who, among other accomplishments, was a distinguished jurist, mining engineer, and diplomat but found time to invent a contraption called the “Leibniz wheel,” a sort of calculator that could carry out the four basic operations of arithmetic. Leibniz subsequently developed a method of calculation called the calculus raciocinator, an innovation his successor George Boole extended by, in Davis’s words, “turning logic into algebra.” (Boole emerges as a deeply sympathetic character in Davis’s pages, rather than as the dry-as-dust figure of other histories. He explained, Davis reports, that he had turned to mathematics because he had so little money as a student to buy books, and mathematics books provided more value for the money because they took so long to work through.) Davis traces the development of this logic, essential to the advent of “thinking machines,” through the workshops and studies of such thinkers as Georg Cantor, Kurt Gödel, and Alan Turing, each of whom puzzled out just a little bit more of the workings of the world–and who, in the bargain, made the present possible.”

The paperback edition was retitled Engines of Logic: Mathematicians and the Origin of the Computer.

Publisher W. W. Norton, 2000

ISBN 0393047857, 9780393047851

257 pages

Review (Mark Johnson, Mathematical Association of America)

Review (Georges Ifrah, The American Mathematical Monthly)

The Universal Computer. The Road from Leibniz to Turing (English, 2001)

Il calcolatore universale: da Leibniz a Turing (Italian, trans. Gianni Rigamonti, 2003)

Na logički pogon: podrijetlo ideje računala (Croatian, trans. Ljerka Vukić and Ognjen Strpić, 2003)