Jacques Rancière: Aisthesis: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art (2011/2013)

Filed under book | Tags: · aesthetics, art, art history, art theory, body, cinema, dance, film, life, literature, music, painting, pantomime, philosophy, photography, poetry, politics, representation, sculpture, theatre, theory

Rancière’s magnum opus on the aesthetic.

“Composed in a series of scenes, Aisthesis–Rancière’s definitive statement on the aesthetic–takes its reader from Dresden in 1764 to New York in 1941. Along the way, we view the Belvedere Torso with Winckelmann, accompany Hegel to the museum and Mallarmé to the Folies-Bergère, attend a lecture by Emerson, visit exhibitions in Paris and New York, factories in Berlin, and film sets in Moscow and Hollywood. Rancière uses these sites and events—some famous, others forgotten—to ask what becomes art and what comes of it. He shows how a regime of artistic perception and interpretation was constituted and transformed by erasing the specificities of the different arts, as well as the borders that separated them from ordinary experience. This incisive study provides a history of artistic modernity far removed from the conventional postures of modernism.”

First published as Aisthesis : Scènes du régime esthétique de l’art, Éditions Galilée, 2011

Translated by Zakir Paul

Publisher Verso Books, 2013

ISBN 1781680892, 9781781680896

304 pages

via falsedeity

Reviews: Hal Foster (London Review of Books), Joseph Tanke (Los Angeles Review of Books), Marc Farrant (The New Inquiry), Ali Alizadeh (Sydney Review of Books), Jean-Philippe Deranty (Parrhesia).

Roundtable discussion with Rancière at Columbia (video, 43 min)

Selected interviews and reviews (in French)

Thomas Harrison: 1910: The Emancipation of Dissonance (1996)

Filed under book | Tags: · 1910s, aesthetics, art, art history, avant-garde, expressionism, literature, music, music history, painting, philosophy, sociology

The year 1910 marks an astonishing, and largely unrecognized, juncture in Western history. In this perceptive interdisciplinary analysis, Thomas Harrison addresses the extraordinary intellectual achievement of the time. Focusing on the cultural climate of Middle Europe and paying particular attention to the life and work of Carlo Michelstaedter, he deftly portrays the reciprocal implications of different discourses—philosophy, literature, sociology, music, and painting. His beautifully balanced and deeply informed study provides a new, wider, and more ambitious definition of expressionism and shows the significance of this movement in shaping the artistic and intellectual mood of the age.

1910 probes the recurrent themes and obsessions in the work of intellectuals as diverse as Egon Schiele, Georg Trakl, Vasily Kandinsky, Georg Lukàcs, Georg Simmel, Dino Campana, and Arnold Schoenberg. Together with Michelstaedter, who committed suicide in 1910 at the age of 23, these thinkers shared the essential concerns of expressionism: a sense of irresolvable conflict in human existence, the philosophical status of death, and a quest for the nature of human subjectivity. Expressionism, Harrison argues provocatively, was a last, desperate attempt by the intelligentsia to defend some of the most venerable assumptions of European culture. This ideological desperation, he claims, was more than a spiritual prelude to World War I: it was an unheeded, prophetic critique.

Publisher University of California Press, 1996

ISBN 0520200438, 9780520200432

264 pages

Reviews (Martino Marazzi; Tyrus Miller; Daniela Bini; Christopher Hailey; Richard Mattin; Dennis Sexsmith)

Review (Laura A. McLary, Monatshefte)

Review (Thomas Kovach, Austrian History Yearbook)

Review (Marco Codebo, Carte Italiane)

Wikipedia

PDF (some images are missing)

View online (HTML, with images)

Oliver I.A. Botar: Prolegomena to the Study of Biomorphic Modernism: Biocentrism, László Moholy-Nagy’s “New Vision” and Ernő Kállai’s Bioromantik (1998)

Filed under thesis | Tags: · aesthetics, art history, avant-garde, biocentrism, biology, constructivism, modernism, nature, photography, science

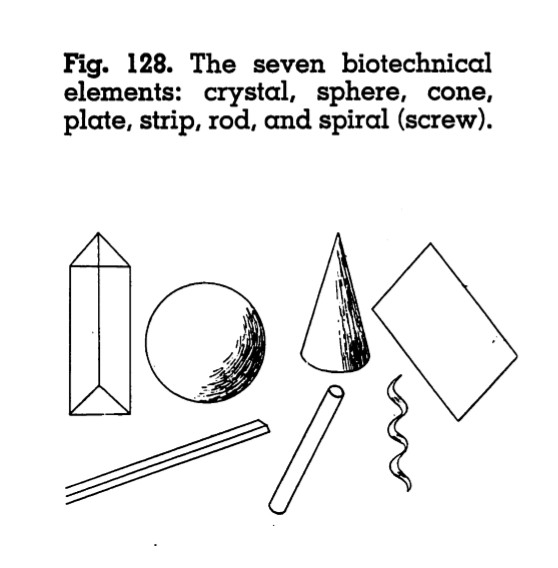

“Focusing on Weimar Germany, I ground the study of biomorphic Modernism in Ernő Kállai‘s 1932 identification of a trend he termed Bioromantik. Kállai wrote from a biocentric position, an amalgam of Nature Romanticism and biologism espoused by Nietzsche, Ernst Haeckel, Ludwig Klages, Oswald Spengler, Raoul Francé and Hans Prinzhorn in the early 20th century, here established as a politically-charged category of intellectual history. Kállai characterized Bioromantik as art, the imagery, forms or themes of which express Monist, Neo-Vitalist, lebensphilosophisch and Organicist, i.e. biocentric concepts such as the life-force, creative/destructive aspects of nature, and our unity with it. The work of artists he cited (Arp, Klee, Moore, Kandinsky, Ernst, etc. ) is biomorphic Modernist in style. Kállai’s conception derives from his realization of the similarity between biomorphic art and scientific photography, here termed the ‘naturamorphic analogy’, a topos traceable to Kandinsky’s pre-war writing.

Probably inspired by Walter Benjamin’s review of Karl Blossfeldt’s photographs, Kállai’s epiphany occurred in the Moholy-Nagy-curated ‘Raum-1’ of the 1929 Film und Foto show in Stuttgart; in effect a three-dimensional statement of his ‘New Vision’ that aestheticized scientific photography, and that — like Moholy’s entire pedagogical project — I show to be rooted in biocentrism. Thus, the profound effect biocentric thinkers had on the milieux Moholy emerged from is discussed: The fin-de-siècle Haeckelian tradition of normative aestheticized scientific imagery is shown to underlie New Vision; the biocentric wing of the Jugendbewegung is revealed as a source of Moholy’s biocentric pedagogy; inspired by Francé, ‘Biocentric Constructivism’ is identified as a discourse engaged in by Mies, Moholy, Lissitzky, Hausmann and Meyer; the Bauhaus, with attention to Gropius, Klee, Kandinsky, Schlemmer and Meyer, is recast as a locus of biocentric ideas.

Like others, Kállai proposed a ‘psychobiological’ explanation for the naturamorphic analogy: the artists’ identity with nature and their consequent intuitive imaging of its unseen aspects also revealed by science. I show how the aestheticization of scientific images effected by New Vision enabled Modernist artists and critics to be exposed to such imagery — an historical alternative to the essentialist explanation that constitutes a basis for research on biomorphic Modernist art.” (Abstract)

Department of the History of Art, University of Toronto, 1998

762 pages