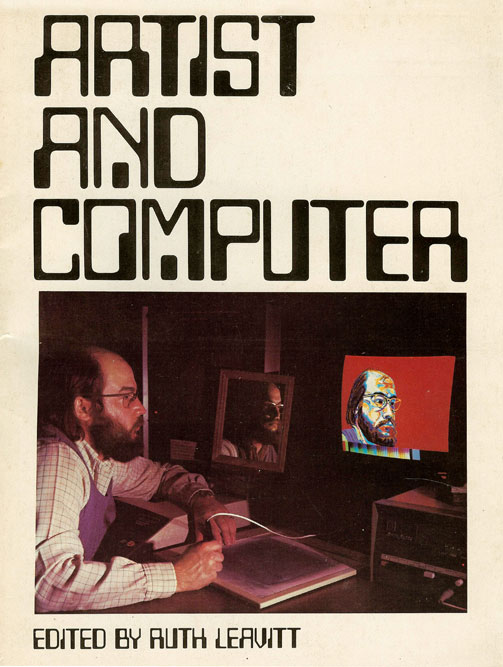

Ruth Leavitt (ed.): Artist and Computer (1976)

Filed under book | Tags: · art, computer art, computer graphics, computing

Creative Computing.

Creative Computing.

Compiled by Ruth Leavitt

Publisher Harmony Books, 1976

ISBN 0517527871, 9780517527870

121 pages

Key terms: computer graphics, oscillons, Aldo Giorgini, Creative Computing, Michael Noll, Ken Knowlton, Lillian Schwartz, cathode ray tube, line printer, Edward Ihnatowicz, Der Blaue Reiter, serigraph, weft, Wassily Kandinsky, Amherst College, acrylic paint, moire patterns, Vera Molnar, artificial creativity

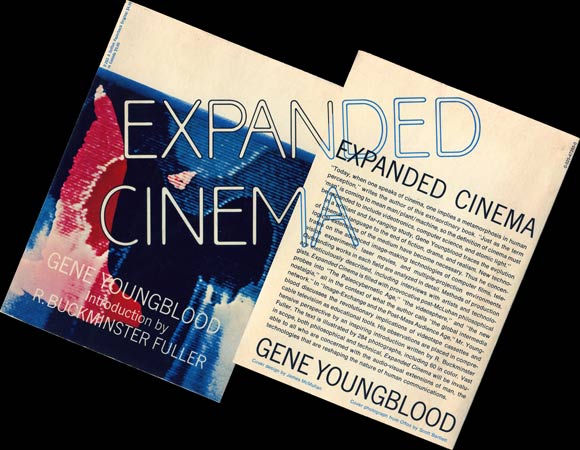

Comment (0)Gene Youngblood: Expanded Cinema (1970)

Filed under book | Tags: · art, art history, computer film, computing, cybernetics, expanded cinema, experimental film, film theory, holography, intermedia, media art, multimedia, technology, television, video, video art

“The first book to consider video as an art form, was influential in establishing the field of media arts. In the book he argues that a new, expanded cinema is required for a new consciousness. He describes various types of filmmaking utilising new technology, including film special effects, computer art, video art, multi-media environments and holography.” (Wikipedia)

Part One: The Audience and the Myth of Entertainment

Part Two: Synaesthetic Cinema: The End of Drama

Part Three: Toward Cosmic Consciousness

Part Four: Cybernetic Cinema and Computer Films

Part Five: Television as a Creative Medium

Part Six: Intermedia

Part Seven: Holographic Cinema: A New World

Key words and phrases: Jordan Belson, expanded cinema, Nam June Paik, Buckminster Fuller, Stan VanDerBeek, videotronic, Ronald Nameth, Carolee Schneemann, John McHale, Expo 67, slit-scan, John Cage, light pen, Gene Youngblood, Otto Piene, Beflix, Howard Wise, KQED, Samadhi, WGBH-TV

Introduction by R. Buckminster Fuller

Publisher E.P. Dutton, New York, 1970

SBN 0525101527

432 pages

Reviews: Paul Cowen (Leonardo, 1972), Thomas Beard (Artforum, 2020), Caroline A. Jones (Artforum, 2020).

Analysis: Adam Sindre Johnson (2010, NO).

PDF (45 MB, no OCR, via Internet Archive, added on 2016-3-2)

PDF, PDF, PDF (5 MB, OCR)

PDF chapters

Grant D. Taylor: The Machine That Made Science Art: The Troubled History of Computer Art 1963-1989 (2004)

Filed under thesis | Tags: · aesthetics, art, art history, computer art, computing, cybernetics, programming, technology

“This thesis represents an historical account of the reception and criticism of computer art from its emergence in 1963 to its crisis in 1989, when aesthetic and ideological differences polarise and eventually fragment the art form. Throughout its history, static-pictorial computer art has been extensively maligned. In fact, no other twentieth-century art form has elicited such a negative and often hostile response. In locating the destabilising forces that affect and shape computer art, this thesis identifies a complex interplay of ideological and discursive forces that influence the way computer art has been and is received by the mainstream artworld and the cultural community at large. One of the central factors that contributed to computer art’s marginality was its emergence in that precarious zone between science and art, at a time when the perceived division between the humanistic and scientific cultures was reaching its apogee. The polarising force inherent in the “two cultures” debate framed much of the prejudice towards early computer art. For many of its critics, computer art was the product of the same discursive assumptions, methodologies and vocabulary as science. Moreover, it invested heavily in the metaphors and mythologies of science, especially logic and mathematics. This close relationship with science continued as computer art looked to scientific disciplines and emergent techno-science paradigms for inspiration and insight. While recourse to science was a major impediment to computer art’s acceptance by the artworld orthodoxy, it was the sustained hostility towards the computer that persistently wore away at the computer art enterprise. The anticomputer response came from several sources, both humanist and anti-humanist. The first originated with mainstream critics whose strong humanist tendencies led them to reproach computerised art for its mechanical sterility. A comparison with aesthetically and theoretically similar art forms of the era reveals that the criticism of computer art is motivated by the romantic fear that a computerised surrogate had replaced the artist. Such usurpation undermined some of the keystones of modern Western art, such as notions of artistic “genius” and “creativity”. Any attempt to rationalise the human creative faculty, as many of the scientists and technologists were claiming to do, would for the humanist critics have transgressed what they considered the primordial mystique of art. Criticism of computer art also came from other quarters. Dystopianism gained popularity in the 1970s within the reactive counter-culture and avant-garde movements. Influenced by the pessimistic and cynical sentiment of anti-humanist writings, many within the arts viewed the computer as an emblem of rationalisation, a powerful instrument in the overall subordination of the individual to the emerging technocracy.” (Abstract)

Ph.D. Thesis

Landscape and Visual Arts, The Faculty of Architecture, The University of Western Australia, 2004

via MediaArtHistories

PDFs (updated on 2016-2-17)

Comment (0)