Michael B. Schiffer: Power Struggles: Scientific Authority and the Creation of Practical Electricity Before Edison (2008)

Filed under book | Tags: · 1800s, electricity, electromagnetism, history of technology, light, technology

In 1882, Thomas Edison and his Edison Electric Light Company unveiled the first large-scale electrical system in the world to light a stretch of offices in a city. This was a monumental achievement, but it was not the beginning of the electrical age. The first electric generators were built in the 1830s, the earliest commercial lighting systems before 1860, and the first commercial application of generator-powered lights (in lighthouses) in the early 1860s. In Power Struggles, Michael Brian Schiffer examines some of these earlier efforts (both successful and unsuccessful) that paved the way for Edison.

After laying out a unified theoretical framework for understanding technological change, Schiffer presents a series of fascinating case studies of pre-Edison electrical technologies, including Volta’s electrochemical battery, Thomas Davenport’s electric motor, the first mechanical generators, Morse’s telegraph, the Atlantic cable, and the lighting of the dome of the U.S. Capitol. Schiffer discusses claims of “practicality” and “impracticality” (sometimes hotly contested) made for these technologies, and examines the central role of the scientific authority—in particular, the activities of Joseph Henry, mid-nineteenth-century America’s foremost scientist—in determining the fate of particular technologies.

These emerging electrical technologies formed the foundation of the modern industrial world. Schiffer shows how and why they became commercial products in the context of an evolving corporate capitalism in which conflicting judgments of practicality sometimes turned into power struggles.

Publisher MIT Press, 2008

Lemelson Center Studies in Invention and Innovation Series

ISBN 0262195828, 9780262195829

420 pages

Lisa Gitelman: Scripts, Grooves, and Writing Machines: Representing Technology in the Edison Era (1999)

Filed under book | Tags: · history of technology, hypertext, kinetoscope, language, phonograph, reading, technology, typewriter, writing

This is a richly imaginative study of machines for writing and reading at the end of the nineteenth century in America. Its aim is to explore writing and reading as culturally contingent experiences, and at the same time to broaden our view of the relationship between technology and textuality.

At the book’s heart is the proposition that technologies of inscription are materialized theories of language. Whether they failed (like Thomas Edison’s “electric pen”) or succeeded (like typewriters), inscriptive technologies of the late nineteenth century were local, often competitive embodiments of the way people experienced writing and reading. Such a perspective cuts through the determinism of recent accounts while arguing for an interdisciplinary method for considering texts and textual production.

Starting with the cacophonous promotion of shorthand alphabets in postbellum America, the author investigates the assumptions—social, psychic, semiotic—that lie behind varying inscriptive practices. The “grooves” in the book’s title are the delicate lines recorded and played by phonographs, and readers will find in these pages a surprising and complex genealogy of the phonograph, along with new readings of the history of the typewriter and of the earliest silent films. Modern categories of authorship, representation, and readerly consumption emerge here amid the un- or sub-literary interests of patent attorneys, would-be inventors, and record producers. Modern subjectivities emerge both in ongoing social constructions of literacy and in the unruly and seemingly unrelated practices of American spiritualism, “Coon” songs, and Rube Goldberg-type romanticism.

Just as digital networks and hypertext have today made us more aware of printed books as knowledge structures, the development and dissemination of the phonograph and typewriter coincided with a transformed awareness of oral and inscribed communication. It was an awareness at once influential in the development of consumer culture, literary and artistic experiences of modernity, and the disciplinary definition of the “human” sciences, such as linguistics, anthropology, and psychology. Recorded sound, typescripts, silent films, and other inscriptive media are memory devices, and in today’s terms the author offers a critical theory of ROM and RAM for the century before computers.

Publisher Stanford University Press, 1999

ISBN 0804732701, 9780804732703

282 pages

Review (Daniel Gilfillan, RCCS, 2002)

Download (removed on 2013-11-12 upon request of the publisher)

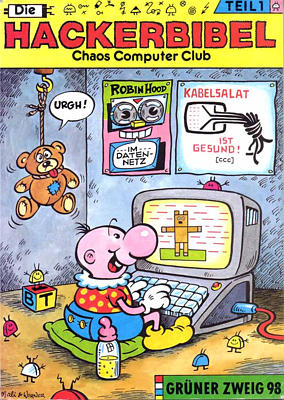

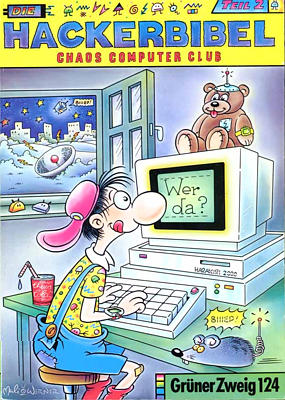

Comment (0)Chaos Computer Club (ed.): Die Hackerbibel, 1-2 (1985, 1988) [German]

Filed under book | Tags: · computing, germany, hacker culture, hacking, history of computing, history of technology, internet, machine, networks, privacy, programming, radio, security, technology, telephone, video

“Die Hackerbibel ist eine Publikation des Chaos Computer Clubs. Sie ist bisher in zwei Ausgaben in den Jahren 1985 und 1988 erschienen. Beide Ausgaben wurden von Wau Holland herausgegeben und vom Verlag Grüne Kraft veröffentlicht.

Die Hackerbibel ist ein Sammelsurium aus Dokumenten und Geschichten der Hacker-Szene, wie beispielsweise die Bauanleitung für den als „Datenklo“ betitelten Akustikkoppler. Sie bietet darüber hinaus Bauanleitungen und andere technische Hintergründe. Die 1. Ausgabe erschien 1985 mit dem Untertitel Kabelsalat ist gesund, und erzielte bis Mitte 1988 eine verkaufte Auflage von 25.000 Exemplaren. Die Ausgabe 2 aus dem Jahr 1988 wird auch Das neue Testament genannt. Die Comic-Zeichnungen der Umschlagbilder sind eine Schöpfung der deutschen Comic-Zeichner Mali Beinhorn und Werner Büsch von der Comicwerkstatt Büsch-Beinhorn. Die Produktion und der Vertrieb der Hackerbibel wurde schon vor 1990 eingestellt. Seit 1999 bietet der CCC eine gescannte und im Volltext verfügbare Version mit weiterem Material, wie Texte von Peter Glaser, eine Dokumentation zu Karl Koch und die Arbeiten von Tron, auf der Chaos-CD an.” (wikipedia)

Die Hackerbibel Teil 1. Kabelsalat ist gesund, Grünen Kraft, Löhrbach, ISBN 3922708986, 260 Seiten

Die Hackerbibel Teil 2. Das neue Testament, Grünen Kraft, Löhrbach, ISBN 3925817247, 260 Seiten

PDF (Teil 1, 56 MB, no OCR, updated on 2024-2-3)

HTML (Teil 1, updated on 2024-2-3)

PDF (Teil 2, 43 MB, no OCR, updated on 2024-2-3)

HTML (Teil 2, updated on 2024-2-3)