Vera Maletic: Body–Space–Expression: The Development of Rudolf Laban’s Movement and Dance Concepts (1987)

Filed under book | Tags: · body, choreography, dance, movement, notation, semiotics

“In May 1926, when the choreographer Rudolf von Laban came to America on an ethnographic mission to record Native American dances, a reporter accosted him before he had even stepped ashore. As Laban recounts in his autobiography, the journalist performed a wild tap dance on deck, proffered his starched cuff to the European dance artist, and said, ‘Can you write that down?’ Laban—who had pioneered a new grammar of movement called Kinetography, or script-dance—scribbled a few dance notation signs on the man’s sleeve. The hyperbolic headline announcing Laban’s arrival read: ‘A New Way to Success. Mr. L. Teaches How to Write Down Dances. You Can Earn Millions With This.’ One entrepreneur, tempted by that prospect, tracked Laban down at his hotel and offered him a fabulous amount of money to teach the Charleston and other dances by correspondence course. Laban spurned the get-rich-quick scheme: he did not want to be a part of what he dismissed as ‘robot-culture.’

To the untrained eye, Kinetography looks esoteric and occult, but to the few who can read it the complex strips of hieroglyphs allow them to recreate dances much as their original choreographers imagined them. Dance notation was invented in seventeenth-century France to score court dances and classical ballet, but it recorded only formal footsteps and by Laban’s time it was largely forgotten. Laban’s dream was to create a ‘universally applicable’ notation that could capture the frenzy and nuance of modern dance, and he developed a system of 1,421 abstract symbols to record the dancer’s every movement in space, as well as the energy level and timing with which they were made. He hoped that his code would elevate dance to its rightful place in the hierarchy of arts, ‘alongside literature and music,’ and that one day everyone would be able to read it fluently.” (from Christopher Turner’s essay in Cabinet magazine, 2009/10)

The intent of this present study is to offer an examination of the origins and development of Laban’s key concepts.

Publisher Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin/New York/Amsterdam, 1987

Volume 75 of Approaches to Semiotics

ISBN 3110107805, 9783110107807

265 pages

via joandleefe

Review (Valerie Preston-Dunlop, Dance Research, 1988)

PDF (40 MB)

See also works on Laban on Monoskop wiki.

Comment (0)Jakob von Uexküll: A Foray Into the Worlds of Animals and Humans: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds (1934–) [DE, EN, FR]

Filed under book | Tags: · animal, biology, environment, meaning, nature, perception, philosophy, plants, psychology, semiotics, subjectivity, time, umwelt

““Is the tick a machine or a machine operator? Is it a mere object or a subject?” With these questions, the pioneering biophilosopher Jakob von Uexküll embarks on a remarkable exploration of the unique social and physical environments that individual animal species, as well as individuals within species, build and inhabit. This concept of the umwelt has become enormously important within posthumanist philosophy, influencing such figures as Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Deleuze and Guattari, and, most recently, Giorgio Agamben, who has called Uexküll “a high point of modern antihumanism.”

A key document in the genealogy of posthumanist thought, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans advances Uexküll’s revolutionary belief that nonhuman perceptions must be accounted for in any biology worth its name; it also contains his arguments against natural selection as an adequate explanation for the present orientation of a species’ morphology and behavior. A Theory of Meaning extends his thinking on the umwelt, while also identifying an overarching and perceptible unity in nature. Those coming to Uexküll’s work for the first time will find that his concept of the umwelt holds new possibilities for the terms of animality, life, and the framework of biopolitics.”

German edition

With illustrations by George Kriszat

Publisher J. Springer, Berlin, 1934, 102 pages

New edition, with the essay “Bedeutungslehre”, with a Foreword by Adolf Portmann, Rowohlt, Hamburg, 1956, 182 pages

English edition

Translated by Claire H. Schiller

In Instinctive Behavior: The Development of a Modern Concept, pp 5-80

Publisher International Universities Press, New York, 1957

Reprinted in Semiotica 89(4), 1992, pp 319-391

New English edition, with the essay “A Theory of Meaning”

Translated by Joseph D. O’Neil

Introduction by Dorion Sagan

Afterword by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young

Publisher University of Minnesota Press, 2010

Posthumanities series, 12

ISBN 9780816658992

272 pages

Reviews and commentaries: Levi R. Bryant (2010), Robert Geroux (Humanimalia, 2012), Franklin Ginn (Science as Culture, 2013).

Streifzüge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen (German, 1934)

Streifzüge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen. Bedeutungslehre (German, 1934/1956)

A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men (English, trans. Claire H. Schiller, 1957)

A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men (English, trans. Claire H. Schiller, 1957/1992)

Mondes animaux et monde humain suivi de La théorie de la signification (French, trans. Philippe Muller, 1965)

A Foray Into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, with a Theory of Meaning (English, trans. Joseph D. O’Neil, 2010)

See also chapters 10-11 of Agamben’s The Open: Man and Animal: Umwelt; Tick (2002/2004)

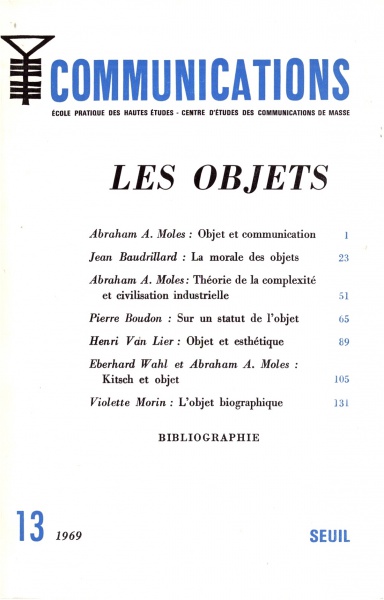

Comment (0)Moles, Baudrillard, Boudon, van Lier, Wahl, Morin: Les objets (1969/71) [French, Spanish]

Filed under book | Tags: · 1968, aesthetics, design, object, philosophy, political economy, psychology, semiotics, sociology, theory

Communications is a biannual social sciences journal founded by Georges Friedmann, Roland Barthes, and Edgar Morin. Soon after its start in 1961 it became a reference publication for media studies and semiotics in France and internationally.

Its first 1969 issue was dedicated to the theory of objects, positioning it “at the confluence of sociology, political economy, social psychology, marketing, philosophy, design and aesthetics” (p 141). At the same time the journal argued for the relevance of the study of objects for governmental institutions such as “the Ministry of Industrial Production, the Ministry of Transport, the customs authorities, the courts, the counterfeits studies, or the National Industrial Property Institute” (p 141).

It can be read as a post-May 1968 attempt to use the concept of object as an agent linking social sciences in order to increase their impact on direct political change, and as well as an early echo of what more than a decade later came to be known as the actor-network theory.

Two years later the magazine appeared in its Spanish translation in book form.

Communications 13

Publisher Centre d’études des communications de masse, École pratique des hautes études, and Seuil, Paris, 1969

139 pages

Les objets (French, 1969), View online

Los objetos (Spanish, trans. Silvia Delpy, 1971/1974)