Les Immatériaux: Épreuves d’écriture & Album et Inventaire (1985) [French]

Filed under catalogue | Tags: · architecture, art, cinema, code, computer art, design, industrial design, installation art, kinetic art, language, machine, painting, photography, robotics, sculpture, simulation, writing

“Les Immatériaux was a landmark exhibition co-curated in 1985 for the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris by philosopher Jean-François Lyotard and design historian and theorist Thierry Chaput, attracting more than 200,000 visitors during the 15 weeks of its duration.

The exhibition brought together a striking variety of objects, ranging from the latest industrial robots and personal computers, to holograms, interactive sound installations, and 3D cinema, along with paintings, photographs and sculptures (the latter ranging from an Ancient Egyptian low-relief to works by Dan Graham, Joseph Kosuth and Giovanni Anselmo). The Centre de Création Industrielle (CCI) – the more ‘sociological’ entity devoted to architecture and design within the Centre Pompidou, which initiated Les Immatériaux – had been planning an exhibition on new industrial materials since at least 1982. Variously titled Création et matériaux nouveaux, Matériau et création, Matériaux nouveaux et création, and, in its last form, La Matière dans tous ses états, this exhibition, first scheduled to take place in 1984, already contained many of the innovative features that found their way into Les Immatériaux.

These features included an emphasis on language as matter, the immateriality of advanced technological materials (from textiles to plastics and holography), exhibits devoted to recent technological developments in food, architecture, music and video, and an experimental catalogue produced using computers. The earlier versions of the exhibition also involved many of the future protagonists of Les Immatériaux, such as Jean-Louis Boissier (among several other faculty members of Université Paris VIII, where Lyotard was teaching at the time) and Eve Ritscher (a London-based consultant on holography). Furthermore, Les Immatériaux benefited from projects pursued concurrently by other groups within the Pompidou which joined Lyotard’s and Chaput’s project when it was discovered that their themes overlapped. Thus, an exhibition project on music videos initiated by the Musée national d’art moderne and a project on electro-acoustic music developed by IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique) were incorporated into it.” (from a study by Anthony Hudek, 2009, edited)

Volume 1 contains an experimental glossary of 50 terms with contributions by twenty-six authors, writers, scientists, artists and philosophers including Nanni Balestrini, Michel Butor, François Châtelet, Jacques Derrida, Bruno Latour and Isabelle Stengers. Volume 2 reproduces the works exhibited.

Publisher Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, March 1985

ISBN 2858502994 (I), 2858503001 (II)

263 (I) and 142 (nonpaginated A4) pages (II)

Épreuves d’écriture (Volume 1, 11 MB, added on 2014-7-30 via Norkhat)

Album et Inventaire (Volume 2, 103 MB, via Arts des nouveaux médias blog of Jean-Louis Boissier)

See also other documents and literature about the exhibition (Monoskop wiki).

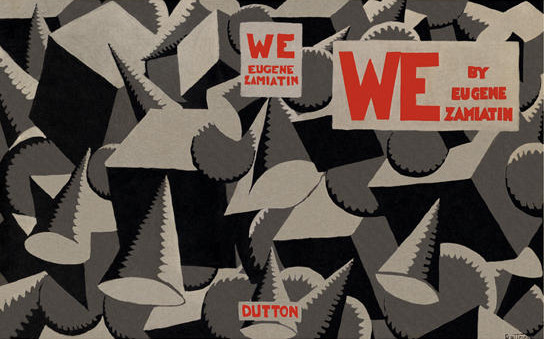

Yevgeny Zamyatin: We (1924–) [EN, DE, CZ, FR, ES, YU, SK, RU, CR, TR, GR]

Filed under fiction | Tags: · machine, science fiction, technology

“Shortly after the nascent Soviet government consolidated its power and launched a program of rapid industrialization, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We (written 1920-21) scandalously questioned the validity of techno-scientific instrumentality, a central principle of societal transformation in Soviet Russia. The first major work of fiction to be censored by the new regime, the novel was smuggled to the West, translated into English, and became an ur-text of twentieth-century science fiction, in particular standing, alongside Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s 1984, as progenitor of a new anti-utopian subgenre warning of the mass cultural homogenization of humanity in the name of progress. Set in a future totalitarian OneState, the novel records the internal conflict and gradual self-awakening of the initially robotlike rocket engineer D-503, torn between his faith in state orthodoxy and yearning for perfect order, on the one hand, and, on the other, his growing awareness of his own disorderly, irrepressible, idiosyncratic subjectivity. The catalyst of this subversive development is the act of writing—paradoxical insofar as this act functions, in the totalitarian system envisioned by the novel, as one of the instruments of the state’s all-pervasive control. […]

Zamyatin’s anti-utopian novel establishes a counterpoint to the purely instrumental technologies conceived by technophiles and tech-nophobes alike insofar as the author consistently deprives technology of its defining characteristic in Industrial Age culture, namely, its functionality. In its place, We imbues technology with various human traits, transforming machines into great vehicles for reflection. As opposed to the aspirations of Soviet ‘new men’ to become machines, Zamyatin’s text features ‘reflexive technologies’ in which pure instrumentality is marred by human idiosyncrasies. In this effort to aesthetically reassess technological potential, to view technology as a medium for contemplation rather than societal change, Zamyatin’s We takes its place within a canon of artistic works that responded to technological advancement with an urge not to exploit but to explore.” (from an essay by Julia Vaingurt, 2012)

The first unabridged Russian edition was published by Chekhov Publishing House in New York, 1952.

English edition

Translated and with a Foreword by Gregory Zilboorg

Introduction by Peter Rudy

Preface by Marc Slonim

Publisher E. P. Dutton, New York, 1924

Reprint, 1952

SBN 0525470395

218 pages

Wikipedia (EN)

We (English, trans. Gregory Zilboorg, 1924/1952)

Wir (German, trans. Gisela Drohla, 1958, EPUB)

My (Czech, trans. Vlasta and Jaroslav Tafels, 6th ed., 1969/2006)

Nous autres (French, trans. B. Cauvet-Duhamel, 1971)

We (English, trans. Mirra Ginsburg, 1972, 21 MB, no OCR)

Nosotros (Spanish, trans. Juan Benusiglio, 1972, unpag., Archive.org)

Mi (Serbo-Croatian, trans. Mira Lalić, 1978)

My (Slovak, trans. Naďa Szabová, 1990)

We (English, trans. Clarence Brown, 1993, MOBI), Audio book (torrent)

Мы (Russian, 2003, pp 211-368, DJVU)

Mi (Croatian, trans. Rafaela Božić Šejić, 2003)

We (English, 2006, trans. Natasha Randall, forew. Bruce Sterling, EPUB, added on 2019-1-16)

Biz (Turkish, trans. Algan Sezgintüredi, 2009)

Εμείς (Greek, trans. Ειρήνη Κουσκουμβεκάκη, 2011), HTML

Katherine Hirt: When Machines Play Chopin: Musical Spirit and Automation in Nineteenth-Century German Literature (2010)

Filed under book | Tags: · 1800s, aesthetics, android, automation, history of literature, language, literature, machine, mechanics, music, music history, musical instruments, philosophy, phonograph

“When Machines Play Chopin brings together music aesthetics, performance practices, and the history of automated musical instruments in nineteenth-century German literature. Philosophers defined music as a direct expression of human emotion while soloists competed with one another to display machine-like technical perfection at their instruments. This book looks at this paradox between thinking about and practicing music to show what three literary works say about automation and the sublime in art.”

Publisher De Gruyter, 2010

Interdisciplinary German Cultural Studies series, 8

ISBN 3110232405, 9783110232400

170 pages

via alcibiades_socrates

Abstract of the thesis (2008)

Comment (0)